Sámi drum

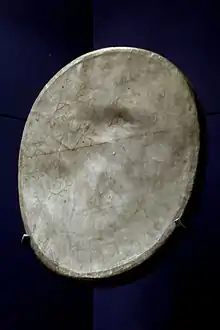

A Sámi drum is a shamanic ceremonial drum used by the Sámi people of Northern Europe. Sámi ceremonial drums have two chiefly two variations, both oval-shaped: a bowl drum in which the drumhead is strapped over a burl, and a frame drum in which the drumhead stretches over a thin ring of bentwood. The drumhead is fashioned from reindeer hide.

In Sámi shamanism, the noaidi used the drum to get into a trance, or to obtain information from the future or other realms. The drum was held in one hand, and beaten with the other. While the noaidi was in trance, his "free spirit" was said to leave his body to visit the spiritual world. When applied for divination purposes, the drum was beaten together with a drum hammer and a vuorbi ('index' or 'pointer') made of brass or horn. Messages could be interpreted based on where the vuorbi stopped on the membrane, and at which symbols.

The patterns on the drum membrane reflect the worldview of the owner and his family, both in religious and worldly matters, such as reindeer herding, hunting, householding as well as relations to their neighbours and to the non-Sámi community.

Many drums were taken out of their use and Sámi ownership during the 18th century. A large number of drums were confiscated by Sámi missionaries and other officials as a part of an intensified Christian mission towards the Sámi. Other drums were bought by collectors. Between 70 and 80 drums are preserved; the largest collection of drums is at the Nordic Museum reserves in Stockholm.

Terminology

The Northern Sámi terms are goavddis, gobdis and meavrresgárri, while the Lule Sámi and Southern Sámi terms are goabdes and gievrie, respectively. Norwegian: runebomme, Swedish: nåjdtrumma;[1] In English it is also known as a rune drum or Sámi shamanic drum.[2][3]

The Northern Sámi name goavddis describes a bowl drum, while the Southern Sámi name gievrie describes a frame drum, coherent to the distribution of these types of drums.[4] Another Northern Sámi name, meavrresgárri, is a cross-language compound word: Sámi meavrres, from meavrit and Finnish möyriä ('kick, roar, mess'), plus gárri from Norwegian kar ('cup, bowl').[5]

The common Norwegian name for the drum, runebomme, is based on an earlier misunderstanding of the symbols on the drum, which saw them as runes.[6] Suggested new names in Norwegian are sjamantromme ("shaman drum")[7] or sametromme ('Sámi drum').[8] The first Swedish name trolltrumma is now considered derogatory, and was based on an understanding of Sámi religion as witchcraft (trolldom). In his Fragments of Lappish Mythology (ca 1840) Læstadius used the term divination drum ("spåtrumma"). In Swedish today, the term commonly used is samiska trumman ('the Sámi drum').[4][9]

Sources on the history of the drums

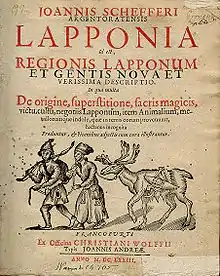

There are four categories of sources to the history of the drums. First the drums themselves, and what might be interpreted from them. Secondly the reports and treatises on Sámi topics during the 17th and 18th centuries, written by Swedish and Dano-Norwegian priests, missionaries or other civil servants, like Johannes Schefferus. The third category are statements from Saami themselves, given to court or other official representatives.[10][11] The fourth are the sporadic references to drums and Sámi shamanism in other sources, such as Historia Norvegiæ (late 12th century).

The oldest mentioning of a Sámi drum and shamanism is in the anonymous Historia Norvegiæ (late 12th century). Here is mentioned a drum with symbols of marine animals, a boat, reindeer and snowshoes. There is also a description of a shaman healing an apparently dead woman by moving his spirit into a whale.[12] Peder Claussøn Friis describes a noaidi spirit leaving the body in his Norriges oc omliggende Øers sandfærdige Bescriffuelse (1632). The oldest description by a Sámi was made by Anders Huitlok of the Pite Sámi in 1642 about this drum that he owned. Anders also made a drawing; his story was written down by the German-Swedish bergmeister Hans P. Lybecker. Huitlok's drum represents a worldview where deities, animals and living and dead people are working together within a given landscape.[13] The court protocols from the trials against Anders Paulsen in Vadsø in 1692 and against Lars Nilsson in Arjeplog in 1691 are also sources.[14]

During the 17th century, the Swedish government commissioned a work to gain more knowledge of the Sámi and their culture. During the Thirty Years' War (1618–48) rumours were spread that the Swedes won their battles with the help of Sámi witchcraft.[15] Such rumours were part of the background for the research that lead to Johannes Schefferus' book Lapponia, published in Latin in 1673.[16] As preparations to Schefferus' a number of "clergy correspondences" ("prästrelationer") was written by vicars within the Sámi districts in Sweden. Treatises by Samuel Rheen, Olaus Graan, Johannes Tornæus and Nicolai Lundius were the sources used by Schefferus.[17][18] In Norway, the main source are writings from the mission of Thomas von Westen and his colleagues from 1715 until 1735. Authors were Hans Skanke, Jens Kildal, Isaac Olsen, and Johan Randulf (the Nærøy manuscript). These books were part instructions for the missionaries and their co-workers, and part a documentation intended for the government in Copenhagen. Late books within this tradition are Pehr Högström's Beskrifning Öfwer de til Sweriges Krona lydande Lapmarker (1747)[19] in Sweden and Knud Leem's Beskrivelse over Finmarkens Lapper (1767) in Denmark-Norway. And especially Læstadius' Fragments of Lappish Mythology (1839–45), which both discusses earlier treatises with a critical approach, and builds upon Læstadius' own experience.

The shape of the drums

Wood

The drums are always oval; the exact shape of the oval would vary with the wood. The remaining drums are of four different types, within two main groups: bowl drums and frame drums.[4]

- Bowl drums, where the wood consists of a burl shaped into a bowl. The burl usually comes from pine, but sometimes from spruce. The membrane is attached to the wood with a sinew.

- Frame drums are shaped by wet or heat bending; the wood is usually pine, and the membrane is sewed to holes in the frame with a sinew.

- Ring drums are made from a naturally grown piece of pine wood. There is only one known drum of this type.

- Angular cut frame drums are made from one piece of wood cut from a three. To bend the wood into an oval, angular cuts are made both in the bottom and the side of the frame. Only two such drums are preserved, both from Kemi Sámi districts in Finland. The partly preserved drum from Bjørsvik in Nordland is also an angular cut frame drum.

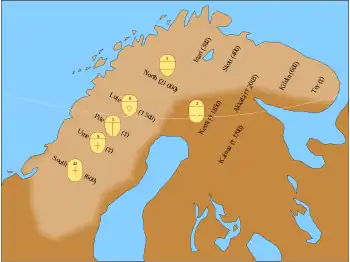

In his major work on Sámi drums, Die lappische Zaubertrommel,[20] Ernst Manker lists 41 frame drums, one ring drum, two angular cut frame drums and 27 bowl drums. Given this numbers, many tend to divide the drums into the two main groups bowl drums and frame drums, seeing the others as variations. Judged by these remaining drums and their known provenance, frame drums seem to be common in the Southern Sámi areas, and bowl drums seem to be common in the Northern Sámi areas. The bowl drum is sometimes regarded as a local adjustment of the basic drum type, this being the frame drum.[4] The frame drum type has most resemblance to other ceremonial drums used by indigenous peoples of Siberia.[4]

The membrane and its symbols

The membrane is made of untanned reindeer hide. Lars Olsen, who described his uncle's drum, the Bindal drum, in 1885, said that the hide usually was taken from the neck of a calf because of its proper thickness; the sex of the calf was probably not important, according to Olsen.[7] The symbols were painted with a paste made from alderbark.[5][20]

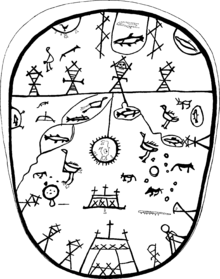

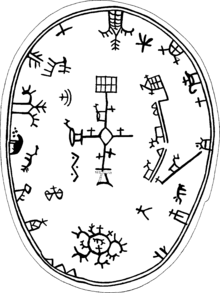

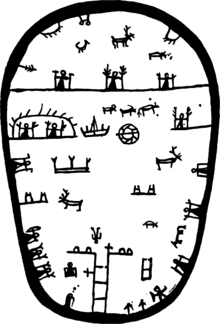

The motives on a drum reflect the worldview of the owner and his family, both in terms of religious beliefs and in their modes of subsistence.[21] A fictitious world is depicted by images of reindeer, both domesticated and wild, and of carnivorous predators that pose a threat to the flock. The modes of subsistence are presented by scenes of wild game hunting, boats with fishing nets, and reindeer herding. Additional scenery on the drum consist of mountains, lakes, people, deities, as well as the camp site with tents and storages houses. Symbols of alien civilization, such as churches and houses, represent the threats from the surrounding and expanding non-Sámi community.[15][22] Each owner chose his set of symbols,[23] and there are no known drums with identical sets of symbols.[17] The drum mentioned in the medieval Latin tome Historia Norvegiæ, with motives such as whales, reindeer, skies and a boat would have belonged to a coastal Sámi. The Lule Sámi drum reflects an owner who found his mode of subsistence chiefly through hunting, rather than herding.

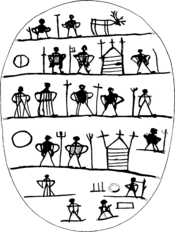

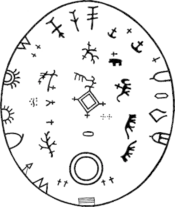

A typhology based on the structure of the patterns can be divided into three main categories:[4]

- Southern Sámi, characterized by the rhombus shaped sun cross in the center

- Central Sámi, where the membrane is divided in two by a horizontal line, often with a sun symbol in the lower section

- Northern Sámi, where the membrane is divided by horizontal lines into three or five separate levels representing the different layers of spiritual worlds: heavens, the world of the living and an underworld.

In Manker's overview of 71 known drums, there are 42 Southern Sámi drums, 22 Central Sámi drums and seven Northern Sámi drums.[20]

The Bindal drum is a typical Southern Sámi drum, with the sun symbol in center. Its last owner also explained that the symbols on the membrane were organized in four directions, according to the cardinal directions around the sun. South is described as the summer side or the direction of life, and contains symbols for the Sámi's life in the fell during summer: the goahti, the storehouse or njalla, the flock of reindeer, and the pastures. North is described as the side of death, and contains symbols for sickness, death and wickedness.[7]

Kjellström and Rydving have summed up the symbols of the drums in these categories: nature, reindeer, bears, moose, other mammals (wolf, beaver, small fur animals), birds, fishes, hunting, fishing, reindeer herding, the camp site – with goahti, njalla and other storehouses, the non-Sámi village – often represented by the church, people, communications (skiing, reindeer with pulk, boats), and deities and their world. Sometimes even the use of the drum itself is depicted.[4][24]

The reindeer herding is mainly depicted with a circular symbol for the pound that was used to gather, mark and milk the flock. This symbol is found on 75% of the Southern Sámi drums, but not on any northern or eastern drums.[4] The symbol for the pound is always placed in the lower half of the drum. Reindeer are represented as singular line figures, as fully modeled figures or by their antlers.[4] The camp site is usually shown as a triangle symbolizing the tent/goahti.[4] The Sámi storehouse (njalla) is depicted on many drums from different areas. The njalla is a small house in bear cache style, built on top of a cut tree. It is usually depicted with its ladder in front.

Sámi deities are shown on several drum membranes. These are the high god Ráðði, the demiurge and sustainer Varaldi olmmai, the thunder and fertility god Horagallis, the weather god Bieggolmmái, the hunting god Leaibolmmái, the sun god Beaivi / Biejjie, the mother goddesses Máttaráhkká, Sáráhkká, Juoksáhkká og Uksáhkká, the riding Ruto who brought sickness and death, and Jábmeáhkká – the empress of the death realms.

Some matters from the non-Sámi world also appears on several drums. These are interpreted as attempts to understand and master the new impulses brought into the Sámi society.[21] Churches, houses and horses appear on several drums, and drums from Torne and Kemi districts show both the city, the church and the lapp commissary.[21]

Interpretation of the drum symbols might be difficult, and there are given different explanations to some of the symbols. There has often been assumed that the Sámi deliberately gave wrong explanations when they presented their drums to missionaries and other Christian audiences, in order to reduce the impression of heathenry and underline the Christian impact of Sami culture.[25][26] There is also an opposite assumption that some of the symbols has been overinterpreted as religious motives while they actually represented matters from timely, everyday life.

Håkan Rydving have evaluated the drum symbols from a perspective of source criticism, and divides them into four categories:[10]

- Preserved drums that were explained by their owners. These are only two drums: Anders Paulsen's drum and the Freavnantjahke gievrie.

- Preserved drums that were explained by other people, contemporary to the owners. These are five drums, four Southern Sami and one Ume Sami.

- Lost drums that were explained by contemporary, either the owner or other people. These are four drums.

- Preserved drums without a contemporary explanation. These are the majority of the 70 known drums.

Rydving and Kjellström have demonstrated that both Olov Graan's drum fra Lycksele[4] and the Freavnantjahke gievrie[10] have been spiritualized through Manker's interpretations: When the explanations are compared, it appears as if Graan relates the symbols to householding and modes of subsistence, where Manker sees deities and spirits. This underlines the problems of interpretation.[4] Symbols that Graan explains as snowy weather, a ship, rain and squirrels in the trees, are interpreted by Manker as the wind god Bieggolmai/Biegkålmaj, a boat sacrifice, a weather god and – among other suggestions – as a forest spirit.[10] At the Freavnantjahke gievrie there is a symbol explained by the owner as "a Sami riding in his pulk behind his reindeer", while Manker suggests that "this might be an ordinary sleigh ride, but we might as well assume that this is the noaidi, the drum owner, going on an important errand into the spiritual world". On the other hand, one might suggest that the owner of the Freavnantjahke gievrie, Bendik Andersen, is under-communicating the spiritual content of the drum when the symbols usually recognized as the three mother goddesses are explained as "men guarding the reindeer".

Accessories

Accessories are mainly the drum hammer and one or two vuorbi to each drum. The drums also had different kinds of cords as well as "bear nails".

The drum hammer (nordsamisk bállin) was usually made of horn, and was T- or Y-shaped, with two symmetric drum heads, and with geometrical decorations. Some hammers have tails made of leather straps, or have leather or tin wires wrapped around the shaft.[20][31] Manker (1938) knew and described 38 drum hammers.[20] The drum hammer was used both when the noaidi went into trance, and together with the vuorbi for divination.

The vuorbi ('index' or 'pointer'; Northern Sámi vuorbi, bajá or árpa; Southern Sámi viejhkie) was made of brass, horn or bone, some times even by wood. The vuorbi was used for divination.

The cords are leather straps nailed or tied to the frame or to the bottom of the drum. They had pieces of bone or metal tied to them. The owner of the Freavnantjahke gievrie, Bendix Andersen Frøyningsfjell, explained to Thomas von Westen in 1723 that the leather straps and their decorations of tin, bone and brass were offers of gratitude to the drum, given by the owner as a response to luck gained from the drum's instructions.[32] The frame of the Freavnantjahke gievrie also had 11 tin nails in it, in a cross shape. Bendix explained them as an indicator of the number of bears killed with aid from the drum's instructions.[32] Manker found similar bear nails in 13 drums.[20] Other drums had baculum from a bear or a fox among the cords.[20]

Using the drum

Isaac Olsen wrote: "hand falder i En Dvalle lige som død og bliver svart og blaa i ansigtet, og mens hand saa liger som død, da kand hand forrette saadant, og mange som er nær død, og siunis som død for menniskens øyen, de kand blive straxt frisk igjen paa samme timme, og naar hand liger i saadan besvimmelse eller Dvalle, da kand han fare vide om kring og forretter meget og kand fortælle mangfoldigt og undelige ting, naar hand opvogner, som hand haver seet og giort, og kand fare vide om landene og i mange steder og føre tidende derfra og føre vise tegen og mercke med sig der fra naar hand er beden der om, og da farer hand og saa i strid i mod sine modstandere og kampis som i En anden verden, indtil at den Ene har lagt livet igien, og er over vunden".[33]

Ernst Manker summarized the use of the drum, regarding both trance and divination:[35]

- before use, the membrane was tightened by holding the drum close to the fire

- the user stood on his knees, or sat with his legs crossed, holding the drum in his left hand

- the vuorbi was placed on the membrane, either on a fixed place or randomly

- the hammer was held in the right hand; the membrane was hit either with one of the hammer heads, or with the flat side of the hammer

- the drumming started at slow pace, and grew wilder

- if the drummer fell into trance, his drum was placed upon him, with the painted membrane facing downwards

- the way of the vuorbi across the membrane, and the places where it stopped, was interpreted as significant

Samuel Rheen, who was a priest in Kvikkjokk 1664–1671, was one of the first to write about Sámi religion. His impression was that many Sámi, but not all, used the drum for divination. Rheen mentioned four matters in which the drum could give answers:

- to seek knowledge about how things were at other places

- to seek knowledge about luck, misfortune, health, and illness

- to cure diseases

- to learn what deity one should sacrifice unto

Of these four ways of use mentioned by Rheen, one knows from other sources that the first of them was only performed by the noaidi.[4] Based on the sources, one might get the impression that the use of the drum was gradually "democratized", so that there in some regions there was a drum in each household, that the father of the household could seek to for advice.[4] Yet, the most original use of the drum – getting into trance, seem to have been a speciality for the noaidi.[4]

Sources seem to agree that in Southern Sámi districts in the 18th century, each household had its own drum. These were mostly used for divination purposes.[36] The types and structure of motives on the Southern Sámi drums confirm a use for divination. On the other hand, the structure of the Northern Sámi drum motives, with its hierarchical structure of spiritual worlds, represent a mythological universe it which it was the noaidi's privilege to wander.[21][36]

The drum was usually brought along during nomadic wanderings. There are also known some cases where the drum was hidden close to one of the regulars' campsites. Inside the lavvu and the goahti, the drum was always placed in the boaššu, the space behind the fireplace that was considered the "holy room" within the goahti.[5]

Several of the contemporary sources describe a duality in the view of the drums: They were seen both as an occult device, and as a divination tool for practical purposes.[34] Drums were inherited. Among those who owned drums in the 18th century, not all of them described themselves as active users of their drum. At least that was what they said when the drums were confiscated.[34]

There is no known evidence that the drum or the noaidi had any role in child birth or funeral rituals.[21]

Some sources suggest that the drum was manufactured with the aid of secret rituals. However, Manker[20] made a photo documentary describing the process of manufacturing the physical drum. Selection of motives for the membrane, or the philosophy behind it, are not described in any sources. It is known that the inauguration of the drum where done by rituals that involved the whole household.

In trance

The noaidi used the drum to achieve a state of trance. He hit the drum with an intense rhythm until he came into a sort of trance or sleep. While in this sleep, his free spirit could travel into the spiritual worlds, or to other places in the material world. The episode mentioned in Historia Norvegiæ tells about a noaidi who traveled to the spiritual world and fought against enemy spirits in order to heal the sick.[12] In the writings of Peder Claussøn Friis (1545–1614) there is described a Sámi in Bergen who could supposedly travel in the material world while he was in trance: A Sámi named Jakob made his spiritual journey to Germany to learn about the health of a German merchant's family.[37]

Both Nicolai Lundius (ca 1670), Isaac Olsen (1717) and Jens Kildal (ca. 1730) describe noaidis traveling to the spiritual worlds where they negotiated with the death spirits, especially Jábmeáhkka – the ruler of the death realms, about the health and life of people.[21] This journey involved a risk for the noaidis own life and health.[15]

Divination and fortune

In the writings of both Samuel Rheen and Isaac Olsen the drum is mentioned as a part of the preparations for bear hunt.[17][21] Rheen says that the noaidi could give information about hunting fortune, while Olsen suggests that the noaidi was able to manipulate the bear to move into hunting range. The noaidi – or drum owner – was a member of the group of hunters, following close to the spear bearer. The noaidi also sat at a prominent place during the feast after the hunting.[21][38]

In Fragments of Lappish Mythology (1840–45), Lars Levi Læstadius writes that the Sámi used his drum as an Oracle, and consulted it when something important came up. "Just like any other kind of fortune-telling with cards or dowsing. One should not consider every drum owner a magician."[39] A common practice was to let the vuorbi move across the membrane, visiting the different symbols. The noaidi would interpret the will of the Gods by the way of the vuorbi.[40] Such practices are described for the Bindal drum, the Freavnantjahke gievrie and the Velfjord drum.

Women

Whether women were allowed to use the drum has been discussed, but no consensus has been reached. On the one hand, some sources say that women were not even allowed to touch the drum,[7] and during migration, women should follow another route than the sleigh that carried the drum.[21] On the other hand, the whole family was involved in the initiation of the drum.[7][21] Also, the participation of joiking women was of importance for a successful soul journey.[21] May-Lisbeth Myrhaug has reinterpreted the sources from the 17th and 18th century, and suggests that there are evidence of female noaidi, even soul traveling female noaidi.[17][41]

Drums after the drum time

.jpg.webp)

In the 17th and 18th century, several actions were made to confiscate drums, both in Sweden and in Denmark-Norway. Thomas von Westen and his colleagues considered the drums to be "the Bible of the Sámi", and wanted to eradicate their idolatry by the roots by destroying or removing the drums.[13] Any uncontrolled, idol-worshipping Sámi were considered a threat to the government.[15] The increased missionary efforts towards the Sámi in the early 18th century might be explained as a consequence of the desire to controle the citizens under the absolute monarchy in Denmark-Norway, and also as a consequence of the increased emphasis on an individual Christian faith suggested in pietism.

In Åsele, Sweden, 2 drums were collected in 1686, 8 drums in 1689 and 26 drums in 1725, mainly of the Southern Sámi type.[21] Thomas von Westen collected ca 100 drums from the Southern Sámi district,[15] 8 of them were collected at Snåsa in 1723. 70 of von Westen's drums were lost in the Copenhagen Fire of 1728.[4] von Westen found few drums during his journeys in the Northern Sámi districts between 1715 and 1730. This might be explained with the advanced christening of the Sámi in north, so that the drums were already destroyed. It might alternatively be explained with diffent use on the drums in Northern and Southern Sámi culture. While the drum was a common household item in Southern Sámi culture, it might have been a rare object, reserved for the few, educated noaidi in Northern Sámi culture.[15][21]

Probably the best-known is the Linné Drum – a drum that was given to Carl Linnaeus during his visits in the northern Sweden. He later gave it to a museum in France, and recently it was brought back to the Swedish National Museum.[43] Three Sámi drums are in the collections of the British Museum, including one bequeathed by Sir Hans Sloane, founder of the museum.[44]

References

- Anonymous 1723/1903

- Liv Helene Willumsen. Witches of the North: Scotland and Finnmark. Brill, 2013. ISBN 978-90-04-25291-2

- Juha Pentikäinen. "The Saami shamanic drum in Rome". Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis; Vol 12 (1987)

- Kjellström & Rydving 1998

- Solbakk 2012

- Lars Ivar Hansen and Bjørnar Olsen. Samenes historie, fram til 1750. Cappelen, 2004. ISBN 978-82-02-19672-1

- Pareli 2010

- The drum in the web exhibition Sámi Faith and Mythology at the Várjjat Sámi Musea

- "Trumman"; Samer.se

- Rydving 2007

- Kildetyper at Roald E. Kristiansen's website Samisk religion.

- "Finnene", from Historia Norvegiæ

- Brita Pollan 2002

- Karin Granqvist. "Till vem ger du din själ, berättelsen om Lars Nilsson på liv och död". In: Fordom då alla djur kunde tala... – Samisk tro i förändring. Åsa Virdi Kroik (ed). Rosima förlag, 2001. ISBN 91-973517-1-7.

- Westman and Utsi 1998

- Johannes Schefferus (1621-1679) in the Web exhibit The Northern Lights Route, Tromsø University Library, 1999

- Mebius 2007

- Kuoljok and Kuhmunen 2014

- Beskrifning öfwer de til Sweriges Krona lydande Lapmarker; fulltext at Runeberg.org

- Manker 1938

- Westman 2001

- Original Swedish quote: "Trummans figurer visar den värld man rörde sig i. Här finns de viktigaste djuren avbildade; vild-och tamrenen, rovdjuren som hotar dem. Här blir näringarnas tydliga; jakten, fisket med båt och nät och renskötseln. Fjäll och sjöar syns. Människor, gudar och gudinnor, liksom vistet [leirplassen] med kåtor och förrådsbodar. Figurerna visar och den främmande religionen och samhället som börjat tränga på. Kyrkor och hus vittnar om den til av omvälvning som många levde i."

- According to Louise Bäckman, they "drew from their own imagination" tecknade utifrån sin egen föreställingsvärld, quoted by Kroik 2007

- The private website thuleia.com has an overview of Shaman's drum symbols in Scandinavia, slightly different from Kjellström and Rydving categories.

- Liv Helene Willumsen. Dømt til ild og bål, trolldomsprosessene i Skottland og Finnmark. Orkana forlag, 2013. 978-82-8104-203-2. Chapter on Anders Paulsen, pages 336-353

- Manker 1950

- Hammer til runebomme fra Nordset, Rendalen, Hedmark Archived 2013-11-13 at the Wayback Machine; at Kulturhistorisk museum, Oslo

- Leif Pareli. "Runebommehammeren fra Rendalen: Et minne etter samer i Sør-Norge i middelalderen?". In: Åarjel-saemieh, nr 4 (1991)

- Pareli, Leif; "En samisk fortid i Rendalen?", in Reindriftsnytt; No. 4, 2005 (pdf)

- "Samer i Sør-Trøndelag og Hedmark i førhistorisk tid"; in NOU 2007: 14 Samisk naturbruk og retts-situasjon fra Hedmark til Troms

- Trumhammare; digitaltmuseum.se

- Anonymous in Qvigstad 1903

- Utdrag fra Relation om lappernes vildfarelser og overtro (1715) på Roald E. Kristiansens nettside Samisk Religion.

- Kroik 2007

- Manker 1938/1950; as quoted by Kjellström & Rydving 1998

- Kristensen 2012

- Excerpt from Norriges oc omliggende Øers sandfærdige Bescriffuelse (1632) at Roald E. Kristiansen's website Samisk religion.

- Ragnhild Myrstad (1996). Bjørnegraver i Nord-Norge: spor etter den samiske bjørnekulten. Tromsø University, section of archeology. (Stensilserie B; 46)

- As quoted by Mebius 2007

- Aage Solbakk. "Samisk mytologi og folkemedisin / Noaidevuohta ja álbmotmedisiidna / Sámi mythology and folk medicine". In: Árbevirolaš máhttu ja dahkkivuoigatvuohta / Tradisjonell kunnskap og opphavsrett. Published by Sámikopiija, Karasjok, 2007. (pdf)

- May-Lisbeth Myrhaug (1997). I modergudinnens fotspor: Samisk religion med vekt på kvinnelige kultutøvere og gudinnekult [In the footprints of the mother goddess, Sámi religion with an emphasis on female agents and goddesses]. Pax forlag. ISBN 82-530-1866-5

- CMAA Collection

- Ahlbäck, Tore; Bergman, Jan (1991). The Saami Shaman Drum: based on papers read at the Symposium on the Saami Shaman Drum held at Åbo, Finland, on the 19th-20th of August 1988. Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History. p. 108. ISBN 9789516498594. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- British Museum Collection

Literature

- Anonymous. (1723) [probably Thomas von Westen] "Underrettning om Rune-Bommens rette Brug iblandt Finnerne i Nordlandene og Finnmarken saaledes, som det har været af Fordum-Tiid". Printed in Just Qvigstad (ed.) Kildeskrifter til den lappiske mythologi; bind 1. Published in the series Det Kongelige Norske Videnskabers Selskabs skrifter 1903. (e-book). pp 65–68

- Birgitta Berglund. "Runebommer, noaider og misjonærer". In: Spor, nr 1, 2004 (pdf)

- Rune Blix Hagen. "Harmløs dissenter eller djevelsk trollmann? Trolldomsprosessen mot samen Anders Poulsen i 1692" In: Historisk tidsskrift; 2002; nr 2/3 (pdf)

- Rolf Kjellström & Håkan Rydving. Den samiska trumman. Nordiska museet, 1988. ISBN 91-7108-289-1

- Roald E. Kristensen. "Samisk religion". In: Guddommelig skjønnhet : kunst i religionene. By Geir Winje et al. Universitetsforlaget, 2012. ISBN 978-82-15-02012-9. Mostly a description of the patterns on the drum mentioned in The Nærøy manuscript

- Åsa Virdi Kroik. Hellre mista sitt huvud än lämna sin trumma. Föreningen Boska, 2007. ISBN 978-91-633-1020-1.

- Sunna Kuoljok and Anna Westman Kuhmunen. Betraktelser av en trumma. Ájtte museums venners småskrift, 2014. Mostly about this drum, which is kept at Ájtte since 2012

- Ernst Manker. Die lappische Zaubertrommel, eine ethnologische Monographie. 2 volumes.

- 1. Die Trommel als Denkmal materieller Kultur. Thule förlag, 1938 (Nordiska museets series Acta Lapponica; 1)

- 2. Die Trommel als Urkunde geistigen Lebens. Gebers förlag, 1950 (Nordiska museets series Acta Lapponica; 6)

- Hans Mebius. Bissie, studier i samisk religionshistoria. Jengel förlag, 2007. ISBN 91-88672-05-0

- Leif Pareli. "To kildeskrifter om Bindalstromma". In: Åarjel-saemieh; no 10. 2010.

- Brita Pollan. Samiske sjamaner: religion og helbredelse. Gyldendal, 1993. ISBN 82-05-21558-8. (ebook in bokhylla.no)

- Brita Pollan (ed). Noaidier, historier om samiske sjamaner. XXXIX, 268 p. Bokklubben, 2002. (Verdens Hellige Skrifter; #14). ISBN 82-525-5185-8

- Håkan Rydving. "Ett metodiskt problem och dess lösning: Att tolka sydsamiska trumfigurer med hjälp av trumman från Freavnantjahke". In: Njaarke: tjaalegh Harranen Giesieakademijeste. Edited by Maja Dunfjeld. Harran, 2007. ISBN 978-82-997763-0-1 (Skrifter fra Sommerakademiet på Harran; 1)

- Aage Solbakk. Hva vi tror på : noaidevuohta - en innføring i nordsamenes religion. ČálliidLágádus, 2008. ISBN 978-82-92044-57-5

- Anna Westman. "Den heliga trumman". In: Fordom då alla djur kunde tala... – Samisk tro i förändring. Edited by Åsa Virdi Kroik. Rosima förlag, 2001. ISBN 91-973517-1-7. Also published as: Anna Westman Kuhmunen. "Den heliga trumman". In: Efter förfädernas sed: Om samisk religion. Edited by Åsa Virdi Kroik. Föreningen Boska, 2005. ISBN 91-631-7196-1.

- Anna Westman and John E. Utsi. Trumtid, om samernas trummor och religion = Gáriid áigi: Sámiid dološ gáriid ja oskku birra. Published by Ájtte and Nordiska museet, 1998. 32 p. ISBN 91-87636-13-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sami drums. |

- The drum; in the web exhibition Sami Faith and Mythology, at the Várjjat Sámi Musea

- (in Swedish) Trumma; digitaltmuseum.se

- Type, origin and location of all surviving Sámi drums; old.no

- (in Swedish) Trumman; samer.se

- Sámi Drums – Then and Now, University of Texas