Saint-Estèphe AOC

Saint-Estèphe is an Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC) for red wine in the Bordeaux region, located in the Médoc subregion. It takes its name from the commune of Saint-Estèphe and is the northernmost of the six communal appellations in Médoc. Five classified growths of 1855 (Bordeaux Grands Crus Classés en 1855) are located within the appellation area. Saint-Estèphe has held AOC recognition since 1936.

| Wine region | |

| Type | AOC |

|---|---|

| Year established | 1936 |

| Country | |

| Size of planted vineyards | 1 230 ha[1] |

| Grapes produced | Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Carménère, Merlot, Malbec, and Petit Verdot |

Historical background

Vines were already being cultivated on the land around Saint-Estèphe in Roman times.[2]

In the Middle Ages the wine business expanded, thanks to English buyers who regularly came to the port of Bordeaux for their wine. The draining of marshland, which began in the 17th century, made larger areas of land available for cultivation.[3]

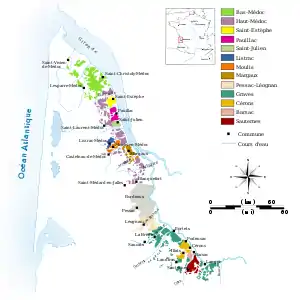

Location

Geographical area

This designation can only be used to denote wines produced in a clearly defined area, corresponding to the commune (or municipality) of Saint-Estèphe.[1]

Geology and orography

The sol de grave (a soil type containing a mixture of gravels, clay and sand), shared by all AOC wines from the Médoc, contains a slightly higher proportion of clay in this particular area.

Climate

The Saint-Estèphe vineyards enjoy the same weather conditions as the Bordeaux-Mérignac meteorological station.

The local climate is, however, affected by the nearby River Garonne. It has the effect of making it more temperate.

Vineyards

Grape varieties grown

The varieties recommended for this appellation are Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Carménère, Côt and Petit Verdot[4]

The AOC regulations do not stipulate the exact proportions to be combined,[4] but in practice most blends consist predominantly of Cabernet Sauvignon. The proportions according to which the six varieties are combined give the wines from each château or estate their own distinctive personality. While some châteaux increase the proportion of Merlot in order to make their young wines easier on the palate, others continue to grow a majority of Cabernet Sauvignon. The châteaux of Cos d'Estournel,[5] Lilian Ladouys[6] and Meyney,[7] for example, use 60% or more of the latter variety.

Methods of cultivation

The density of planting required is at least 7,000 vines per hectare. The rows should be positioned no more than 1.5 metres apart and the distance between any two vines within a row should not be less than 0.8 metres.[4] The vines are pruned every year before the first leaves have opened fully.[4] The aim is to keep a maximum of 12 renewal buds per vine (each renewal bud will produce a side branch bearing a cluster of grapes). Authorized pruning methods include the so-called "médocaine" method (the local name for Guyot pruning), with either cane pruning or cane and spur pruning, and the so-called "à cots" method (spur pruning), based on the methods traditionally called Cordon de Royat (unilateral cordon) or éventail (fan).[4]

For vines planted less than 1.4 metres apart, the height of the foliage must be at least 0.6 times the distance between rows, while for vines planted between 1.4 and 1.5 metres apart, the height should be increased to at least 0.7 times the distance between rows. This rule is designed to ensure the growth of sufficient foliage for the grapes to ripen well.[4]

Harvesting

By law the yield per plot is restricted to 9,500 kg per hectare, which is the equivalent of 14 bunches per vine for Petit Verdot grapes and 12 bunches per vine for other varieties. This quantity should (only) give a yield per hectare of 57 hectolitres (per hectare) once the process of wine-making has been completed.

The harvesting method is not stipulated in the AOC regulations.[4] In fact many estates now use harvesting machines, although some prestigious estates, such as the châteaux of Lilian Ladouys[6] and Meyney,[7] still harvest by hand. This practice is defended on the basis that it is possible to sort at the same time as harvesting, not to mention the further round of sorting that takes place when the harvest is loaded onto a sorting table in the wine shed.

Wine-making

On arrival in the chai, the grapes are destemmed and crushed before being transferred to non-oxidizing[6][7] concrete[7] or wooden tanks. The maceration of grape skins mixed with grape must begins. Alcoholic fermentation is activated using selected commercial yeasts or yeasts that are naturally present in the bloom on the skins of the grapes. The wine sheds are equipped with temperature-controlled tanks,[6] making it possible to direct the fermentation process by preventing temperatures from rising too high and then, at the very end, reheating the harvested materials. This procedure is designed to maintain an environment in which the yeasts can efficiently transform the sugar into alcohol, and the colour (anthocyanins) and tannins can best be extracted. Fermentation is a long process, lasting between two and four weeks, depending on the estate and varying from year to year.

Once the wine has been drained off, the grape residue is pressed. The pressed wine is tasted. Based on the outcome of this test of taste and smell, which takes into account grape variety and vintage, a decision is made as to whether or not the press wine is good enough to be included in the final blend. The next step is to store the wine in a tank (or sometimes in a barrel[6]) at a temperature situated between 20 and 25 °C, which allows malolactic fermentation to take place.

At this stage the quality of each tank is assessed individually before small amounts from each batch are combined in test conditions. This sample blend then serves as a yardstick for the blends about to be created, each estate preserving the distinctive character of its own wines while reflecting the overall style of that particular vintage. This process, which is carried out by the wine-maker and an oenologist, is crucial to the end result.

Once the wines have been blended on a large scale, they are matured in tanks (in the case of smoother vintages) or in barrels (in the case of more robust vintages). Maturing a wine means storing it for long periods in cellars where the temperature is controlled and where it remains undisturbed apart from rackings that take place every three months.[6] Maturing a wine that is stored in barrels can take between six and eighteen months.[6]

Wine

Analytical criteria

The minimum alcohol content is set at 11% by volume. When it is decided that a wine needs enriching, the alcohol content should not exceed 13.5%[4] by volume. When the harvest is of such exceptional quality that it does not need enriching at all, there is no upper limit to the naturally occurring alcohol content allowed.

In the case of batches of wine produced for the commercial market, the process of alcoholic fermentation must be halted (less than two grams per litre of fermentable sugar) and malolactic fermentation carried out. (less than 0.30 grams per litre of malic acid). The volatile acidity of the wine must not exceed 13.26 milliequivalents (i.e. 0.79 expressed as grams per litre of acetic acid or 0.65 g/L of H2SO4) in the first year of aging (up to 31 July). After that the limit is set at 16.33 mEq. (i.e. 0.98 expressed as grams per litre of acetic acid or 0.80 g/L of H2SO4).[4]

Tasting

Considerable variations in terroir (the soil, weather conditions and wine-making traditions associated with a particular vineyard) mean that the wines produced differ according to the estates from which they originate. Nevertheless, they all share certain typical characteristics. The authoritative French wine guide published by Hachette, refers to Saint-Estèphe wines as having a finer acidity, tannic structure and colour than other Médoc wines.[1] With maturity this wine acquires stronger fruit flavours and becomes more rounded and elegant. It is definitely a wine that improves with age, and can be kept for some considerable time.[1] In his book Bordeaux, Robert M. Parker Jr. states that the wines of Saint-Estèphe "have the reputation of being the slowest to mature, and the toughest, most tannic wines."

Matching food and wine

Saint-Estèphe complements red meats particularly well. In his book, L'École des alliances, les mets et les vins (A Course in Match-making, Food and Wine), Pierre Casamayor writes, "red meats have one essential quality, which is that their proteins render even the most virile tannins attractive."[8]

Thanks to its powerful structure, Saint-Estèphe is a match for red meats such as roast rib of beef[9] or agneau de Pauillac à la cuisson de sept heures[10] (local Pauillac lamb cooked for seven hours according to a traditional recipe) or, once it has aged, for a truffle sauce or for furred game meats cooked in a marinade or when aged, with game.[1]

Production

The Saint-Estèphe vineyards cover 1,230 hectares (3,000 acres), and in 2008 they produced 54,200 hectolitres of wine.[1] This volume of wine represents on average 8.7 million bottles per year.[2]

The wine is produced by 136 different producers: 80 of them are members of cooperatives and 56 are private estates.[2]

Classified Saint-Estèphe estates

In the Bordeaux Wine Official Classification of 1855, there are no First Growths in Saint-Estèphe, but two Second Growths. The classified estates of Saint-Estèphe are:

- Second Growths

- Third Growths

- Fourth Growths

- Fifth Growths

Saint-Estèphe also has the distinction of having produced a large number of other wines (Cru Bourgeois or non-classified) that are nevertheless of excellent quality, some of them being comparable to or better than some of the Grand Cru Classé wines. Château Phélan Ségur, Château Les Ormes de Pez, and Château Haut-Marbuzet are just a few such wines.

References

- Le Guide Hachette des Vins 2010, page 381.

- Page of AOC Saint-Estèphe on the website medoc-bordeaux.com, accessed 30 January 2010.

- Histoire du Médoc on the website medoc-bordeaux.com, accessed 30 January 2010.

- Datasheet for AOC Saint-Estèphe on the website legifrance.gouv.fr, accessed on 15 January 2010.

- Château Cos d'Estournel Archived 11 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine on the website estournel.com, accessed 31 January 2010.

- Section vin Archived 7 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine on the website chateaulilianladouys.com, accessed 31 January 2010.

- Section présentation, le vin on the website meyney.fr, accessed 31 January 2010.

- L'école des alliances, les mets et les vins, Hachette pratique, octobre 2000, ISBN 2-01-236461-6, page 179.

- Guide hachette des vins 2010, page 382

- Château Phélan Ségur on the website phelansegur.com