Sande society

Sande, also known as zadεgi, bundu, bundo and bondo, is a women's initiation society in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea and the Ivory Coast. The Sande society initiates girls into adulthood by rituals including female circumcision.[1] It is alleged by its supporters to confer fertility, to instill notions of morality and proper sexual comportment, and to maintain an interest in the well-being of its members throughout their lives.

In addition, Sande champions women's social and political interests and promotes their solidarity vis-a-vis the Poro, a complementary institution for men. The Sande society masquerade is a rare and perhaps unique African example of a wooden face mask controlled exclusively by women – a feature that highlights the extraordinary social position of women in this geographical region.

Geographic extent

The Sande society is found throughout the Central West Atlantic Region, an ethnically plural and linguistically diverse region that lies within the littoral forest zone bounded by the Scarcies River and Cape Palmas.[3] As early as 1668, a Dutch geographer named Olfert Dapper published a description of the "Sandy" society as it existed in the Cape Mount region of Liberia, based on a first-hand account that seems to date from 1628.[4][5]

Anthropologists believe that Sande originated in Gola society and spread to the neighboring Mende and Vai; other ethnic groups adopted Sande as recently as the present century. Today this social institution is found among the Bassa, Gola, Kissi, Kpelle, Loma, Mano and Vai of Liberia; the Kono, Limba, Mende, Sherbro, Temne and Yalunka of Sierra Leone; and in the northern and eastern extension of these ethnic groups in Guinea.

Common features

The common features of all of these women's associations are:

- Group initiation in a secluded area of the forest.

- The use of Sande society names in lieu of birth names following initiation.

- Scarification.

- Body modification in the form of piercings and skin removal.

- Hierarchically ranked female leadership.

- A pledge of secrecy vis-a-vis men and uninitiated girls.

- Female genital mutilation performed by female specialists.

An additional characteristic Sande feature – the wooden helmet mask and raphia costume worn by Sande leaders – is absent among the Kono, Loma, and Mano.

Regional variations

Although anthropologists and art historians sometimes describe the Sande society as an all-embracing, pan-ethnic association, there is considerable cultural variation throughout the region.[6][7] The ethnic groups where the Sande Society is present speak languages belonging to three language families (Mande, Mel and Kru). They may be animists, or like the Mende, Vai and Yalunka, they may have significant Muslim populations.

In some societies, such as the Bassa, Kissi and Kono, the complementary men's society, the Poro, may not be present. Among the Dei and Loma, the Sande society regularly admits male blacksmiths as ritual specialists, and in Gola society, the spirit represented by the mask is considered to be male rather than female. Indeed, the quintessential symbol of Sande among many of the ethnic groups where this woman's association is present – the wooden helmet mask – is entirely absent among the Kpelle, Kono, Loma and Mano.

Initiation and transformation

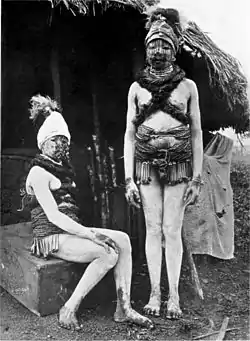

Sequestration and female circumcision

Adolescent girls are initiated as a group during the post-harvest dry season in a specially cleared area of forest surrounding the town or village. The initiation period varies from several weeks to several months, depending upon such factors as the initiate's age, lineage membership, school attendance, and ethnicity.

In the past, the girls are said to have remained in the forest for upwards of one year, during which time they made rice farms for the Sande leadership. In addition to the initiate's labor, Sande leaders receive a substantial initiation fee from the girl's father or her prospective husband, as a girl may not marry before initiation.

According to Carol MacCormack:

- "Shortly after entering the Bundu bush, girls experience the surgery distinctive of a Bundu woman in which the clitoris and part of the labia are excised. It is a woman, the Majo (Mende), or head of a localized Bundu chapter, who usually performs this surgery. [A] Bundu woman told me that excision helps women to become prolific bearers of children. A Majo reputed 'to have a good hand' will attract many initiates to her Bundu bush, increasing her social influence in the process. Informants also said the surgery made women clean."[1]

Many women who survive the "surgery" will have lifelong complications. Not only are the genitalia disfigured, multiple lacerations are made in the skin so that large scars will mark the initiate for life.

Post-initiation education

After their wounds have healed, the girls are instructed in domestic skills, farming, sexual matters, dancing, and medicine. Specialized skills such as dyeing cloth may be taught to girls who demonstrate special aptitude or, according to some sources, to girls from high-ranking landowning lineages. But at least one anthropologist has suggested that the girls "learn little more than they already knew before they entered the bush ... or than they would learn at that stage of their lives if they did not become secret society members."[8]

In this view, the girls' training is more symbolic than utilitarian, for the essential lessons learned are deference to authority and an absolute respect for secrecy. In contrast, another source suggests that "the emphasis is not on learning new skills so much as on learning new attitudes toward their work. Instead of doing this work in the role of a daughter, they begin to anticipate the role of wife who must work cooperatively with her co-wives and her husband's female kin."[1]

Bonding

MacCormack notes that the shared experience of a lengthy stay in the forest and the risk of the surgery binds the girls together as a cohesive social group. But:

- "There are pleasures to be enjoyed as well as ordeals, and the girls go gladly into the initiation grove. Food is plentiful since the initiation season occurs in the post-harvest dry season and each girl's family is obliged to send large quantities of rather special food into the initiation grove on her behalf. There are also special Bundu songs, dances and stories to be enjoyed around the fire in the evening. The stories usually end with an instructive moral linked to Bundu laws given to the living by ancestresses of the secret society."[1]

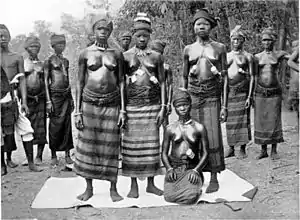

Return to the community

At the conclusion of their initiation the girls are ritually "washed" and returned to the community as marriageable adults. They emerge from the forest dressed in their finest clothes, with new names signifying their newly achieved adult status and their persona (i.e. rank) in the association's ritual hierarchy. In some areas, cicatrization in the form of teeth support the view (held by the uninitiated) that the girls were devoured by a forest spirit that has now returned them to society; although death and rebirth imagery is not a universal feature of Sande initiation.

Symbolic meaning

According to Jedrej (1986), the Sande initiation ritual centers on several sets of spatial and temporal oppositions, such as those between village (public) and forest (secret) space, on the one hand, and ancestral time (sacred) and the present-day (profane) on the other. The initiate's moral transformation from child to adult occurs in three stages (novice > virgin > bride) marked by public scarfication, skin removal, and/or body piercings in the town or village. A key symbol of these performances is the initiate's metaphorical movement through water, the realm of the ancestors.[4][9][10]

Unique masking traditions in Liberia

See full article: Mende masquerades

Women generally do not wear masks in western Africa, but in this region the most numerous and most important wood masks are produced for use by women for the Sande. Several types of masks, some in wood but many made of leather, fur, and cloth, are used in conjunction with the counterpart male initiation society, the Poro. The masks used in these societies have common iconographic features throughout the region, but each mask is known by an individual person name corresponding to the spiritual force believed to be associated with the local Poro or Sande society chapters.[11]

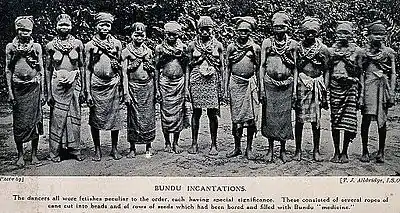

Iconography of the Mende/Vai helmet mask

This type of mask, also often called bundu, is worn at initiation ceremonies celebrating a successful transition into womanhood.[12] In Mende society "the term sowo refers to both the supernatural entity which represents the women's secret society, and the masked dancer whose polished black anthropomorphic helmet mask and black raphia-covered body the spirit invests with its presence and power."[13]

In addition to the mask's appearance at girls' initiation ceremonies, sowo also "appears in public to mark important civic events such as the visits of important dignitaries and the coronations and funerals of important chiefs. On these occasions, her presence is a means of impressing on the community the unity and strength of the female corporate body as well as Sande's political significance."[14]

According to Dubinskas, the Mende say a finely carved sowo mask is nyande ("good," "pretty," "beautiful" and aesthetically "pleasing") when it includes the following elements, each of which has a symbolic meaning:

- Full forehead = Wisdom, intelligence

- Somnolent, downcast eyes = Modesty

- Shining black color = Mystery

- Neck rings = Health and prosperity (as well as the mask's mythic rise out of the water)

- Birds = Messengers between spirits and humans

- Cowries = Wealth

- White cloth = Ritual purity

- Fish, snakes, tortoises = The riverine home of sowo

- Antelope horns and lasimo (scripture) = "Good medicine" (hale nyande)

- Three-legged cooking pot = represents sowo as a repository of women's knowledge, and as a symbol of domesticity

In addition, the mask's eyes should be slightly oversized (indicating knowledge and wisdom), while the mask's nose and mouth should be slightly smaller than human-sized (for a discussion of Mende feminine beauty).[7][13]

Dubinskas writes that the mask represents the ideals of womanhood and the ideal image of feminine beauty, an everywoman versus a woman of extraordinary power, desired by all but attained by an elite few. As such, the mask "embodies and mediates contradictions between traditional feminine role models in the society and the actual political and economic power which women do have access to, if not consistently, then at least regularly and generally enough for that power to call forth a significant symbolic focus in the ideological realm."[13]

Alternating roles of the Sande and Poro societies

Throughout this region, the complementarity of men's and women's gender roles – evident in such diverse activities as farming, cloth production, and musical performances – reach full expression. The women's Sande and men's Poro associations alternate political and ritual control of "the land" (a concept embracing the natural and supernatural worlds) for periods of three and four years respectively. During Sande's sovereignty, all signs of the men's society are banished.

At the end of this three-year period, the Sande leadership "turns over the land" to its counterparts in the Poro Society for another four years, and after a rest period the ritual cycle begins anew. The alternating three- and four-year initiation cycles for women and men respectively are one example of the widespread use of the numbers 3 and 4 to signify the gender of people, places and events; together the numbers equal seven, a sacred number throughout the region (Leopold 1983; Sawyerr and Todd 1970).

Death threats against Liberian journalist

Journalist Mae Azango received death threats from several Sande society women for reporting on Sande female circumcision practices in 2012.[15][16]

References

- MacCormack, Carol P. (1975). Dana Raphael (ed.). Bundu: Political Implications of Female Solidarity in a Secret Society. The Hague: Mouton. ISBN 0-202-01151-8.

- [T. J. Alldridge, The Sherbro and its Hinterland, (1901)]

- d'Azevedo, Warren L. (1962). "Some Historical Problems in the Delineation of A Central West Atlantic Region". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 96 (2): 512–538. Bibcode:1962NYASA..96..512D. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb50146.x.

- Holsoe, Svend E. (1980). "Notes on the Vai Sande Society in Liberia". Ethnologische Zeitschrift. 1: 97–109.

- Dapper, O. (1668). Naukeurige Beschrijvinge der Afrikaensche Gewesten van Egypten, Barbaryen, Libyen, Biledulgerid, Guinea, Ethiopiën, Abyssine ... Amsterdam: J. van Meurs.

- d'Azevedo, Warren L. (1980). "African Art of the West Atlantic Coast: Transition in Form and Content, by Frederick Lamp. L. Kahan Gallery, New York, 1979". African Arts. 14 (1).

- Boone, Sylvia Ardyn; Busselle, Rebecca (1986). Radiance from the waters : ideals of feminine beauty in Mende art. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03576-4.

- Bledsoe, Caroline H. (1999). Women and marriage in Kpelle society. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1019-8.

- MacCormack, Carol P. (1982). Carol P. MacCormack (ed.). Ethnography of fertility and birth. London u.a.: Acad. Pr. ISBN 0-12-463550-4.

- Jedrej, M. C (1986). "Cosmology and Symbolism on the Central Guinea Coast". Anthropos. 81: 497–515.

- Siegmann, William C. (2009). African art a century at the Brooklyn Museum. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum. ISBN 9780872731639.

- Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Art : guide to the collection. [Birmingham, Ala]: Birmingham Museum of Art. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-904832-77-5.

- Dubinskas, Frank A. (1976). "Everywoman" and the "Super"-Woman: An Investigation of the Sowo, Spirit of the Mende Women's Secret Society, Sande: The Relation of Her Form as an Ideological Construction to its Bases in the Social and Economic Position of Women. Unpublished manuscript.

- Day, Lynda Rose (1988). The Female Chiefs of the Mende, 1885-1977: Tracing the Evolution of an Indigenous Political Institution. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Bonnie Allen (March 29, 2012). "Female Circumcision Temporarily Stopped in Liberia". The World. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- Jina Moore (29 May 2012). "Mae Azango exposed a secret ritual in Liberia, putting her life in danger". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

Other sources and further reading

- Abraham, Arthur. Mende Government and Politics under Colonial Rule, Sierra Leone Univ. Press (dist.by Oxford), 1978. ISBN 0-19-711638-8

- Bledsoe, Caroline. Women and Marriage in Kpelle Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-8047-1019-8

- Boone, Sylvia A. Radiance from the Waters: Ideals of Feminine Beauty in Mende Art. (Yale Publications in the History of Art 34). New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986. ISBN 0-300-03576-4

- Dapper, O. Naukeurige Beschrijvinge der Afrikaensche Gewesten van Egypten, Barbaryen, Libyen, Biledulgerid, Guinea, Ethiopiën, Abyssine ..., Amsterdam: J. van Meurs, 1668.

- Day, Lynda Rose. The Female Chiefs of the Mende, 1885-1977: Tracing the Evolution of an Indigenous Political Institution. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1988.

- d'Azevedo, Warren L. (1962) Some Historical Problems in the Delineation of A Central West Atlantic Region. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 96: 512-538.

- d'Azevedo, Warren L. (1980) African Art of the West Atlantic Coast: Transition in Form and Content, by Frederick Lamp. L. Kahan Gallery, New York, 1979. African Arts 14(1): 81-88.

- Dubinskas, Frank A. "Everywoman" and the "Super"-Woman: An Investigation of the Sowo, Spirit of the Mende Women's Secret Society, Sande: The Relation of Her Form as an Ideological Construction to its Bases in the Social and Economic Position of Women. Unpublished manuscript, 1976.

- Easmon, M. C. F. (1958) Madam Yoko: Ruler of the Mendi Confederacy. Sierra Leone Studies (n.s.) 11: 165-168.

- Holsoe, Svend E. (1980) Notes on the Vai Sande Society in Liberia. Ethnologische Zeitschrift 1: 97-109.

- Jedrej, M. C. (1990) Structural Aspects of a West African Secret Society. Ethnologische Zeitschrift 1: 133-142.

- Jedrej, M. C. (1986) Cosmology and Symbolism on the Central Guinea Coast. Anthropos 81: 497-515.

- Lamp, Frederick (1985) Cosmos, Cosmetics, and the Spirit of Bondo, African Arts, 18:3, 28-43+98-99.

- Leopold, Robert S. (1983) The Shaping of Men and the Making of Metaphors: The Meaning of White Clay in Poro and Sande Initiation Society Rituals. Anthropology 7(2): 21-42.

- MacCormack, Carol P. [Hoffer] Madam Yoko: Ruler of the Kpa Mende Confederacy. In Woman, Culture and Society, edited by Michele Z. Rosaldo and Louise Lamphere, pp. 171–187, 333-334. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1974. ISBN 0-8047-0850-9

- MacCormack, Carol P. [Hoffer]. Bundu: Political Implications of Female Solidarity in a Secret Society. In Being Female: Reproduction, Power, and Change, edited by Dana Raphael, pp. 155–163. The Hague: Mouton, 1975. ISBN 0-202-01151-8

- MacCormack, Carol P. [Hoffer]. Health, Fertility and Birth in Moyamba District, Sierra Leone. In Ethnography of Fertility and Birth. C. P. MacCormack, ed. pp. 115–139. NY: Academic Press, 1982. ISBN 0-12-463550-4

- Phillips, Ruth. B. (1995) Representing Woman: Sande Masquerades of the Mende of Sierra Leone. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. ISBN 0-930741-45-5

- Sawyerr, Harry and S. K. Todd (1970) The Significance of the Numbers Three and Four among the Mende of Sierra Leone. Sierra Leone Studies (n.s.) 26: 29-36.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sande society. |