Traditional African masks

Traditional African masks play an important role in certain traditional African rituals and ceremonies.

Masks serve an important role in rituals or ceremonies with varied purposes like ensuring a good harvest, addressing tribal needs in time of peace or war, or conveying spiritual presences in initiation rituals or burial ceremonies. Some masks represent the spirits of deceased ancestors. Others symbolize totem animals, creatures important to a certain family or group. In some cultures, like the Kuba culture of Zaire, masks represent specific figures in tribal mythology, like a king or a rival to the ruler.

The wearer of the mask is often believed to be able to communicate to the being symbolized by it, or to be possessed by who or what the mask represents.

Ritual and ceremonial masks are an essential feature of the traditional culture of the peoples of a part of Sub-Saharan Africa, e.g. roughly between the Sahara and the Kalahari Desert. While the specific implications associated with ritual masks widely vary in different cultures, some traits are common to most African cultures. For instance, masks usually have a spiritual and religious meaning and they are used in ritual dances and social and religious events, and a special status is attributed to the artists that create masks to those that wear them in ceremonies. In most cases, mask-making is an art that is passed on from father to son, along with the knowledge of the symbolic meanings conveyed by these masks. African masks come in all different colours, such as red, black, orange, and brown.

In most traditional African cultures, the person who wears a ritual mask conceptually loses his or her human life and turns into the spirit represented by the mask itself.[1] This transformation of the mask wearer into a spirit usually relies on other practices, such as specific types of music and dance, or ritual costumes that contribute to the shedding of the mask-wearer's human identity. The mask wearer thus becomes a sort of medium that allows for a dialogue between the community and the spirits (usually those of the dead or nature-related spirits). Masked dances are a part of most traditional African ceremonies related to weddings, funerals, initiation rites, and so on. Some of the most complex rituals that have been studied by scholars are found in Nigerian cultures such as those of the Yoruba and Edo peoples, rituals that bear some resemblance to the Western notion of theatre.[2]

Since every mask has a specific spiritual meaning, most traditions comprise several different traditional masks. The traditional religion of the Dogon people of Mali, for example, comprises three main cults (the Awa or cult of the dead, the Bini or cult of the communication with the spirits, and the Lebe or cult of nature); each of these has its pantheon of spirits, corresponding to 78 different types of masks overall. It is often the case that the artistic quality and complexity of a mask reflects the relative importance of the portrayed spirit in the systems of beliefs of a particular people; for example, simpler masks such as the kple kple of the Baoulé people of Côte d'Ivoire (essentially a circle with minimal eyes, mouth and horns) are associated with minor spirits.[3]

Masks are one of the elements of great African art that have most evidently influenced European and Western art in general; in the 20th century, artistic movements such as cubism, fauvism and expressionism have often taken inspiration from the vast and diverse heritage of African masks.[4] Influences of this heritage can also be found in other traditions such as South- and Central American masked Carnival parades.

Subject and style

African masks are usually shaped after a human face or some animal's muzzle, albeit rendered in a sometimes highly abstract form. The inherent lack of realism in African masks (and African art in general) is justified by the fact that most African cultures clearly distinguish the essence of a subject from its looks, the former, rather than the latter, being the actual subject of artistic representation. An extreme example is given by nwantantay masks of the Bwa people (Burkina Faso) that represent the flying spirits of the forest; since these spirits are deemed to be invisible, the corresponding masks are shaped after abstract, purely geometrical forms.

Stylish elements in a mask's looks are codified by the tradition and may either identify a specific community or convey specific meanings. For example, both the Bwa and the Buna people of Burkina Faso have hawk masks, with the shape of the beak identifying a mask as either Bwa or Buna. In both cases, the hawk's wings are decorated with geometric patterns that have moral meanings; saw-shaped lines represent the hard path followed by ancestors, while chequered patterns represent the interaction of opposites (male-female, night-day, and so on)[5]

Traits representing moral values are found in many cultures. Masks from the Senufo people of Ivory Coast, for example, have their eyes half closed, symbolizing a peaceful attitude, self-control, and patience. In Sierra Leone and elsewhere, small eyes and mouth represent humility, and a wide, protruding forehead represents wisdom. In Gabon, large chins and mouths represent authority and strength.[5] The Grebo of the Ivory Coast carve masks with round eyes to represent alertness and anger, with the straight nose representing an unwillingness to retreat.[5]

Animals

Animals are common subjects in African masks. Animal masks might actually represent the spirit of animals, so that the mask-wearer becomes a medium to speak to animals themselves (e.g. to ask wild beasts to stay away from the village); in many cases, nevertheless, an animal is also (sometimes mainly) a symbol of specific virtues. Common animal subjects include the buffalo (usually representing strength, as in the Baoulé culture),[6] crocodile, hawk, hyena, warthog and antelope. Antelopes have a fundamental role in many cultures of the Mali area (for example in Dogon and Bambara culture) as representatives of agriculture.[7] Dogon antelope masks are highly abstract, with a general rectangular shape and many horns (a representation of abundant harvest. Bambara antelope masks (called chiwara) have long horns representing the thriving growth of millet, legs (representing roots), long ears (representing the songs sung by the working women at harvest time), and a saw-shaped line that represents the path followed by the Sun between solstices.[6] A 12th/13th century mural from Old Dongola, the capital of the Nubian kingdom of Makuria, depicts dancing masks decorated with cowrie shells imitating some animal with long snouts and big ears.[8]

A common variation on the animal-mask theme is the composition of several distinct animal traits in a single mask, sometimes along with human traits. Merging distinct animal traits together is sometimes a means to represent unusual, exceptional virtue or high status. For example, the Poro secret societies of the Senufo people of the Ivory Coast have masks that celebrate the exceptional power of the society by merging three different "danger" symbols: antelope horns, crocodile teeth, and warthog fangs.[9] Another well-known example is that of kifwebe masks of the Songye people (Congo basin), that mix the stripes of a zebra (or okapi), the teeth of a crocodile, the eyes of a chameleon, the mouth of an aardvark, the crest of a rooster, the feathers of an owl and more.[6]

Feminine beauty

Another common subject of African masks is a woman's face, usually based on a specific culture's ideal of feminine beauty. Female masks of the Punu people of Gabon, for example, have long curved eyelashes, almond-shaped eyes, thin chin, and traditional ornaments on their cheeks, as all these are considered good-looking traits.[3] Feminine masks of the Baga people have ornamental scars and breasts. In many cases, wearing masks that represent feminine beauty is strictly reserved to men.[5]

One of the well-known representations of female beauty is the Idia mask of Benin. It is believed to have been commissioned by King Esigie of Benin in memory of his mother. To honor his dead mother, the king wore the mask on his hip during special ceremonies.[10]

Ancestor masks (masks of the dead)

As the veneration of defunct ancestors is a fundamental element of most African traditional cultures, it is not surprising that the dead is also a common subject for masks. Masks referring to dead ancestors are most often shaped after a human skull. A well-known example is the mwana pwo (literally, "young woman") of the Chokwe people (Angola), that mixes elements referring to feminine beauty (well-proportioned oval face, small nose and chin) and other referring to death (sunken eye sockets, cracked skin, and tears); it represents a female ancestor who died young, venerated in rites such as circumcision rites and ceremonies associated to the renewal of life.[11] As veneration of the dead is most often associated with fertility and reproduction, many dead-ancestor masks also have sexual symbols; the ndeemba mask of the Yaka people (Angola and DR Congo), for example, is shaped after a skull complemented with a phallic-shaped nose.[12]

A special class of ancestor masks are those related to notable, historical or legendary people. The mwaash ambooy mask of the Kuba people (DR Congo), for example, represents the legendary founder of the Kuba Kingdom, Woot, while the mgady amwaash mask represents his wife Mweel.[13]

Materials and structure

The most commonly used material for masks is wood, although a wide variety of other elements can be used, including light stone such as steatite, metals such as copper or bronze, different types of fabric, pottery, and more. Some masks are painted (for example using ochre or other natural colorants). A wide array of ornamental items can be applied to the mask surface; examples include animal hair, horns, or teeth, sea shells, seeds, straw, egg shell, and feathers. Animal hair or straw are often used for a mask's hair or beard.

The general structure of a mask varies depending on the way it is intended to be worn. The most common type applies to the wearer's face, like most Western (e.g., carnival) masks. Others are worn like hats on the top of the wearer's head; examples include those of the Ekhoi people of Nigeria and Bwa people of Burkina Faso, as well as the famous chiwara masks of the Bambara people.[6] Some masks (for example those of the Sande society of Liberia and the Mende people of Sierra Leone, that are made from hollow tree stumps) are worn like helmets covering both the head and face. Some African cultures have mask-like ornaments that are worn on the chest rather than the head of face; this includes those used by the Makonde people of East Africa in ndimu ceremonies.[14]

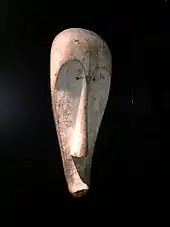

Ngil mask from Gabon or Cameroon; wood colored with kaolin (chiny clay); by Fang people; Ethnological Museum of Berlin (Germany). Worn with full costume in a night masquerade to settle disputes and quell misbehavior, this calm visage was terrifying to wrong-doers

Ngil mask from Gabon or Cameroon; wood colored with kaolin (chiny clay); by Fang people; Ethnological Museum of Berlin (Germany). Worn with full costume in a night masquerade to settle disputes and quell misbehavior, this calm visage was terrifying to wrong-doers BaKongo masks from the Kongo Central region

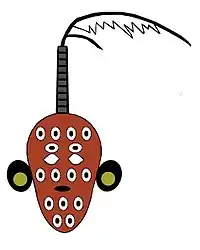

BaKongo masks from the Kongo Central region Zoomorphic mask as depicted on a Makurian mural from Old Dongola (12th/13th century)

Zoomorphic mask as depicted on a Makurian mural from Old Dongola (12th/13th century) A mask of the Mitsogo people of Gabon

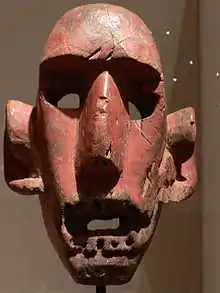

A mask of the Mitsogo people of Gabon Wabele mask, Senufo people, Brooklyn Museum

Wabele mask, Senufo people, Brooklyn Museum Doei (or Kwere), female ancestor mask, Tanzania

Doei (or Kwere), female ancestor mask, Tanzania Mwaash aMbooy Mask Brooklyn Museum

Mwaash aMbooy Mask Brooklyn Museum A copper and wood mask from Central Africa

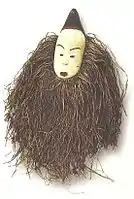

A copper and wood mask from Central Africa Helmet Mask for Sande Society Brooklyn Museum

Helmet Mask for Sande Society Brooklyn Museum Commercial masks for sale a in a shop in the Mwenge Makonde market, Dar es Salaam

Commercial masks for sale a in a shop in the Mwenge Makonde market, Dar es Salaam

Commercially-produced masks

As African masks are largely appreciated by Europeans, they are widely commercialized and sold in most tourist-oriented markets and shops in Africa (as well as "ethnic" shops in the Western World). As a consequence, the traditional art of mask-making has gradually ceased to be a privileged, status-related practice, and mass production of masks has become widespread. While, in most cases, commercial masks are (more or less faithful) reproductions of traditional masks, this connection is weakening over time, as the logics of mass-production make it harder to identify the actual geographical and cultural origins of the masks found in such venues as curio shops and tourist markets. For example, the Okahandja market in Namibia mostly sells masks that are produced in Zimbabwe (as they are cheaper and more easily available than local masks), and, in turn, Zimbabwean mask-makers reproduce masks from virtually everywhere in Africa rather than from their own local heritage.[15]

See also

- Tribal art

- African art

- African sculpture

- Picasso's African Period

- FESTIMA, a festival celebrating traditional masks

- Toloy

Notes

- This idea has been literally portrayed in the well-known novel Things Fall Apart by Nigerian writer Chief Chinua Achebe. While the author hints at the importance of the masks themselves in the same novel, masked elders are particularly hostile towards the missionaries, a symbolic representation of the opposition of traditional Nigerian culture (as represented by the mask-spirits) and the new values brought along by European Christians.

- Analogies between Nigerian ceremonies and the theatre of Ancient Greece (as well as the Western theatre in general) have been developed by the Nobel Prize winning Nigerian writer Chief Wole Soyinka. Soyinka wrote dramas based on the Yoruba traditions and, conversely, he has "africanized" classical works of the Western theatre such as Euripides' The Bacchae or Bertolt Brecht's The Threepenny Opera.

- See Faces of the Spirit

- Fauvism at Art Snap

- See African Masks Symbolism

- See African Masks

- Many agricultural societies and associations in Mali have a stylized representation of an antelope in their symbols.

- Martens-Czarnecka 2008, p. 120.

- See Icons of Power

- See Bortolot

- A male variant of this mask is called cihongo.

- See Images of Ancestors

- See Portraits of Rulers

- See Physical characteristics of African Tribal Masks

- See Namibia, Lonely Planet 2007, ISBN 978-88-6040-119-9

References

- African Masks Symbolism

- The Art of the African Mask, University of Virginia

- Faces of the Spirit, University of Virginia

- Icons of Power, University of Virginia

- Images of Ancestors, University of Virginia

- Portraits of Rulers, University of Virginia

- Physical characteristics of African Tribal Masks, Rebirth African Art Gallery

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives, Idia: The First Queen Mother of Benin. In Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- Lommel, Andreas Masks, Their Meaning and Function, Ferndale Editions, London, orig. Atlantis Verlag Zurich 1970 — introduction, after Himmelheber Afrikanische Masken ISBN 0-905746-11-2

- Martens-Czarnecka, Malgorzata (2008). "A Scene of a Ritual Dance (Old Dongola-Sudan)". Etudes et Travaux (PDF). XXII.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Genesis: ideas of origin in African sculpture, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on African masks

- For spirits and kings: African art from the Paul and Ruth Tishman collection, an exhibition catalog

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on African masks