Genital modification and mutilation

The terms genital modification and genital mutilation can refer to permanent or temporary changes to human sex organs. Some forms of genital alteration are performed on adults with their informed consent at their own behest, usually for aesthetic reasons or to enhance stimulation. However, other forms are performed on people who do not give informed consent, including infants or children. Any of these procedures may be considered modifications or mutilations in different cultural contexts and by different groups of people.

Reasons

Religious

The vast majority of genital cutting in the world is done for religious motives (though not all members of genital cutting religions adhere to the practice). In both cases, genital cutting is done as a:

- Rite of passage. In Islam, typically from childhood to puberty, and in Judaism. Brit milah is the ritual in which boys' names are made public to the extended family and the community.

- Religious identity. Both in Judaism and Islam, genital cutting for males is seen as a badge of membership to the community.

- Repress sexual pleasure and desire. While this is explicitly recognized within Judaism, in the Muslim world, no such claims are made for male circumcision. However, many traditional cultures in East Africa and other Muslim jurisdictions have made such claims for female genital cutting. This claim is currently very controversial with numerous research papers and fatawa (religious legal ruling) arguing over the permissibility and purpose of female genital cutting.[1][2]

Body modification

Many types of genital modification are performed at the behest of the individual, for personal, sexual, aesthetic or cultural reasons. Penile subincision, or splitting of the underside of the penis, is widespread in the traditional cultures of Indigenous Australians. This procedure has taken root in Western body modification culture, the modern primitives. Meatotomy is a form that involves splitting of the glans penis alone, while bisection is a more extreme form that splits the penis entirely in half.

Genital piercings and genital tattooing may be performed for aesthetic reasons, but piercings have the benefit of increasing sexual pleasure for the pierced individual or their sex partners.[3][4]

Similarly, Pearling involves surgical insertion of small, inert spheres under the skin along the shaft of the penis for the purpose of providing sexual stimulation to the walls of the vagina. Similar to tattooing, genital scarification is primarily done for aesthetic reasons by adding cosmetic scars to the skin. The genital decoration by scars is an ancient tradition in many cultures, both for men and women.[5] The Hanabira-style (Japanese for petal) is a special form of scarification originating in Japan, it involves the decoration of the mons pubis.[6][7]

Clitoris enlargement may be achieved temporarily through the use of a clitoral pump, or it may be achieved permanently through the application or injection of testosterone. Penis enlargement is a term for various techniques used to attempt to increase the size of the penis, though the safety and efficacy of these techniques are debated.

Voluntary sex reassignment

People who are transgender or intersex may undergo sex reassignment surgery in order to modify their bodies to match their gender identity. Not all transgender people elect to have these surgeries, but those who do usually see an improvement in their sexual lives as well as their mental and emotional well-being.[8] Some of the surgical procedures are breast augmentation and vaginoplasty (creation of a vagina) for trans women and mastectomy (breast removal), metoidioplasty (elongation of the clitoris), and phalloplasty (creation of a penis) for trans men. Trans women may also benefit from hair removal and facial feminization surgery, while some trans men may have liposuction to remove fat deposits around their hips and thighs.

Hijra, a third gender found in the Indian subcontinent, may opt to undergo castration.[9]

Involuntary sex assignment

Intersex children and children with ambiguous genitalia may be subjected to surgeries to "normalize" the appearance of their genitalia. These surgeries are usually performed for cosmetic benefit rather than for therapeutic reasons. Most surgeries involving children with ambiguous genitalia are sexually damaging and may render them infertile.[10] For example, in cases involving male children with micropenis, doctors may recommend the child be reassigned as female.[11] The Intersex Society of North America objects to elective surgeries performed on people without their informed consent on grounds that such surgeries subject patients to unnecessary harm and risk.[12]

In some cases, a child's gender may be reassigned due to genital injury. There have been at least seven cases of healthy male infants being reassigned as female due to circumcision damaging their penises beyond repair,[13][14][15][16] including the late David Reimer (born Bruce Reimer, later Brenda Reimer), who was the subject of John Money's John/Joan case; an unnamed American child, who was awarded $750,000 by Judge Walter McGovern of the Federal District Court after a military doctor was found guilty of medical malpractice in 1975; and an unnamed child who was circumcised at Northside Hospital, who received an undisclosed amount of money from the hospital.

In Andhra Pradesh, India, a 75 year old surgeon working at the Kurnool Government Hospital in Kadappa named as Naganna was arrested by the CB-CID for conducting forced sex change surgeries on kidnapped victims for nearly a decade by using a nationwide network of hijras.[17][18][19]

Some homophobic societies force sex reassignment to non-heterosexual. The Aversion Project is a well-known example.

As treatment

If the genitals become diseased, as in the case of cancer, sometimes the diseased areas are surgically removed. Females may undergo vaginectomy or vulvectomy (to the vagina and vulva, respectively), while males may undergo penectomy or orchiectomy (removal of the penis and testicles, respectively). Reconstructive surgery may be performed to restore what was lost, often with techniques similar to those used in sex reassignment surgery.

During childbirth, an episiotomy (cutting part of the tissue between the vagina and the anus) is sometimes performed to increase the amount of space through which the baby may emerge. Advocates of natural childbirth and unassisted birth state that this intervention is often performed without medical necessity, with significant damage to the person giving birth.

Hymenotomy is the surgical perforation of an imperforate hymen. It may be performed to allow menstruation to occur. An adult individual may opt for increasing the size of her hymenal opening, or removal of the hymen altogether, to facilitate sexual penetration of her vagina.

The world's first penis reduction surgery was performed in 2015, on a 17-year-old boy who had an American football-shaped penis as a result of recurrent priapism.[20]

Self-inflicted

A person may engage in self-inflicted genital injury or mutilation such as castration, penectomy, or clitoridectomy. The motivation behind such actions vary widely; it may be done due to skoptic syndrome, personal crisis related to gender identity, mental illness, self-mutilation, body dysmorphia, or social reasons.

During armed conflict

Genital mutilation is common in some situations of war or armed conflict, with perpetrators using violence against the genitals of men, women, and non-binary people.[21] These different forms of sexual violence can terrorize targeted individuals and communities, prevent individuals from reproducing, and cause tremendous pain and psychological anguish for victims.

Females

Female genital mutilation

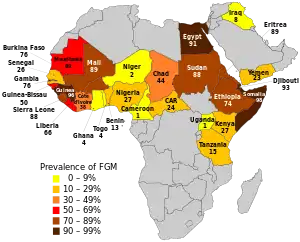

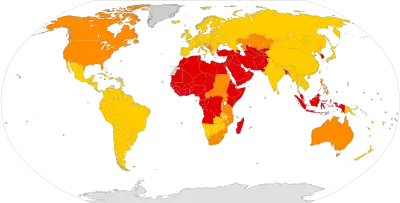

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting (FGC), female circumcision, or female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), refers to "all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other surgery of the female genital organs whether for cultural, religious or other non-therapeutic reasons."[23] It is not the same as the procedures used in gender reassignment surgery or the genital modification of intersex persons. It is practised in several parts of the world, but the practice is concentrated more heavily in Africa, parts of the Middle East, and some other parts of Asia. Over 125 million women and girls have experienced FGM in the 29 countries in which it is concentrated.[24]

Over eight million have been infibulated, a practice found largely in Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia and Sudan.[25] Infibulation, the most extreme form of FGM (known as Type III), consists of the removal of the inner and outer labia and closure of the vulva, while a small hole is left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood; afterwards the vagina will be opened after the wedding for sexual intercourse and childbirth (see episiotomy). In the past several decades, efforts have been made by global health organizations, such as the WHO, to end the practice. FGM is condemned by international human rights instruments. The Istanbul Convention prohibits FGM (Article 38).[26]

FGM is also considered a form a violence against women by the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women, which was adopted by the United Nations in 1993; it states: "Article Two: Violence against women shall be understood to encompass, but not be limited to, the following: (a) Physical, sexual and psychological violence occurring in the family, including [...] female genital mutilation [...]".[27] However, because of its importance in traditional life, it continues to be practised in many societies.[28]

Hymenorrhaphy

Hymenorrhaphy refers to the practice of thickening the hymen, or, in some cases, implanting a capsule of red liquid within the newly created vaginal tissue. This new hymen is created to cause physical resistance, blood, or the appearance of blood, at the time that the individual's new husband inserts his penis into her vagina. This is done in cultures where a high value is placed on female virginity at the time of marriage. In these cultures, a woman may be punished, perhaps violently, if the community leaders deem that she was not virginal at the time of consummation of her marriage. Individuals who are victims of rape, who were virginal at the time of their rape, may elect for hymenorrhaphy.

Labia stretching

Labia stretching is the act of elongating the labia minora through manual manipulation (pulling) or physical equipment (such as weights).[29][30] It is a familial cultural practice in Rwanda,[29] common in Sub-Saharan Africa,[31] and a body modification practice elsewhere.[30] It is performed for sexual enhancement of both partners, aesthetics, symmetry and gratification.[29][30]

Labiaplasty and vaginoplasty

Cosmetic surgery of female genitalia, known as elective genitoplasty, has become pejoratively known as ″designer vagina″. In May 2007, an article published in the British Medical Journal strongly criticised this craze, citing its popularity being rooted in commercial and media influences.[32][33] Similar concerns have been expressed in Australia.[32]

Some women undergo vaginoplasty or labiaplasty procedures to alter the shape of their vulvas to meet personal or societal aesthetic standards.[34] The surgery itself is controversial, and critics refer to the procedures as "designer vagina".[35][36][37]

In the article Designer Vaginas by Simone Weil Davis, she talks about the modification of woman's vagina and the outside influences women are pressured with, which can cause them to feel shame towards their labia minora. She states that the media, such as pornography, creates an unhealthy view of what a "good looking vagina" is and how women feel that their privates are inferior and are therefore pressured to act upon that mindset. These insecurities are forced upon women by their partners and other women as well.[38] Also leading to a surge of these types of procedures is increased interest in non-surgical genital alterations, such as Brazilian waxing, that make the vagina more visible to judgment. The incentive to participate in labia- and vaginoplasty may also come about in an effort to manage women's physical attributes and their sexual behavior, treating their vagina as something needing to be managed or controlled and ultimately deemed "acceptable".[39]

Clitoral hood reduction

Clitoral hood reduction is a form of hoodplasty. When performed with the consent of the adult individual, it can be considered an elective plastic surgery procedure for reducing the size and the area of the clitoral hood (prepuce) in order to further expose the clitoral glans of the clitoris; the therapeutic goal is thought to improve the sexual functioning of the woman, and the aesthetic appeal of her vulva. The reduction of the clitoral prepuce tissues usually is a sub-ordinate surgery within a labiaplasty procedure for reducing the labia minora; and occasionally within a vaginoplasty procedure. When these procedures are performed on individuals without their consent, they are considered a form of female genital mutilation.

Males

Castration

Castration in the genital modification and mutilation context is the removal of the testicles. Sometimes the term (meaning "cutting") (or "total castration") is also used to refer to penis removal, but that is less common. Castration has been performed in many cultures throughout history, but is now rare. In the twenty-first century, castration has been reported among slave boys in South Asia. It should not be confused with chemical castration.

Hemi-castration

The removal of one testicle (sometimes referred to as unilateral castration) is usually done in the modern world only for medical reasons.

Circumcision

Circumcision is the surgical removal of part or all of the foreskin from the penis. It is usually performed for religious, cultural or medical reasons and leaves some or all of the glans permanently exposed. Jews and many Americans typically have their infants circumcised during the neonatal period, while Filipinos, most Muslims and African communities such as the Maasai and Xhosa circumcise in teenage years or childhood as an initiation into adulthood.

In modern medicine, circumcision may be used as treatment for severe phimosis or recurrent balanitis that has not responded to more conservative treatments. Advocacy is often centered on preventive medicine, while opposition is often centered on human rights (particularly the bodily integrity of the infant when circumcision is performed in the neonatal period) and the potentially harmful side effects of the procedure.[41][42] Neonatal circumcision is generally safe when done by an experienced practitioner, with complications being rare, though death has been reported in some cases.[43]

The World Health Organization estimates that one-third of the world's men are circumcised; the majority of circumcised male population is located in Muslim countries and in the United States, although there are various explanations for why the infant circumcision rate in the US is different from comparable countries.[40]

In 2012 the American Academy of Pediatrics stated that health benefits of non-therapeutic circumcision aren't great enough to recommend it for every newborn, and that the benefits outweigh the risks, so that the procedure may be done for families who choose it.[44]

The Danish College of General Practitioners has defined non-medical circumcision as mutilation.[45]

Foreskin restoration

Foreskin restoration is the partial recreation of the foreskin after its removal by circumcision. Surgical restoration involves grafting skin taken from the scrotum onto a portion of the penile shaft. Nonsurgical methods involve tissue expansion by stretching the penile skin forward over the glans penis with the aid of tension. Nonsurgical restoration is the preferred method as it is less costly and typically yields better results than surgical restoration. A foreskin restoration device may be of help to men pursuing nonsurgical foreskin restoration. While restoration cannot recreate the nerves or tissues lost to circumcision, it can recreate the appearance and some of the function of a natural foreskin.

Infibulation

Infibulation literally means to close with a clasp or a pin. The word is used to include suturing of the foreskin over the head of the penis.

Infibulation is seen in rock art in Southern Africa.[46][47]

Early Greek infibulation consisted of piercing the foreskin and applying a gold, silver or bronze ring (annulus), a metal clasp (fibula) or pin. This was done for aesthetic reasons. The Greeks also used a nonsurgical form of infibulation by wearing a kynodesme. Infibulation in Romano-Greek culture is attested as early as Aulus Cornelius Celcus (25 BC-50 AD) and as late as Oribasisus (325–405 AD).[48]

In the Victorian era, both in the UK and in the United States, routine infibulation was second only to circumcision in the "war on masturbation" and was used in orphanages and mental institutions, supported by leading physicians.[48][49]

In modern times, male infibulation may be performed for personal preferences or as part of BDSM.

Emasculation

Also known as total castration or nullification, emasculation is the combination of castration and penectomy.

Due to the high risk of death from bleeding and infection, it was often considered a punishment equivalent to a death sentence. It was part of the eunuch-making of the Chinese court, and it was widespread in the Arab slave trade. A castrated slave was worth more, and this offset the losses from death.[50]

Nullification or "nullo" is the term used by the modern body modification community.

In modern-day South Asia, some members of Hijra communities reportedly undergo emasculation. It is called nirwaan and seen as a rite of passage.[51]

Pearling

Pearling or genital beading is a form of body modification, the practice of permanently inserting small beads made of various materials beneath the skin of the genitals—of the labia, or of the shaft or foreskin of the penis. As well as being an aesthetic practice, this is usually intended to enhance the sexual pleasure of partners during vaginal or anal intercourse.

Penectomy

Penectomy involves the partial or total amputation of penis. Sometimes, the removal of the entire penis was done in conjunction with castration, or incorrectly referred to as castration. Removing the penis was often performed on eunuchs and high ranking men who would frequently be in contact with women, such as those belonging to a harem. The hijra of India may remove their penis as an expression of their gender identity. In the medical field, removal of the penis may be performed for reasons of gangrene or cancer. Penis removal may occur through unintentional genital injury, such as during routine neonatal circumcision mishaps.[52][53][54][55][56][57]

In the ulwaluko circumcision ceremony, which is performed by spear, accidental penectomy is a serious risk.[58]

Penis removal for purposes of assault or revenge is overwhelmingly a female-on-male crime, particularly in Thailand. In the United States In 1907 Bertha Boronda sliced off her husband's penis with a straight razor.[59] Lorena Bobbit infamously removed her husband's penis in 1993. In some circumstances it may be possible to reattach the penis.

Penile subincision

Penile subincision is a form of genital modification involves a urethrotomy and vertically slitting the underside of the penis from the meatus towards to the base. It was performed by people of some cultures, such as the Indigenous Australians, the Arrente, the Luritja, the Samburu, the Samoans, and the Native Hawaiians. It may also be performed for personal preference. Penile subincision may leave a man with an increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases, issues with fertility (due to lack of control over what direction the sperm goes after ejaculation), and may require a man to sit down while urinating.[60] When the surgery is not performed in a hospital or by a licensed medical professional, complications such as infection, exsanguination, or permanent damage are major concerns.

Penile superincision

A dorsal slit (also known as superincision) is an incision made along the upper length of the foreskin with the intention to expose the glans penis without removing skin or tissue.

The practice appears to have occurred in Ancient Egypt, though not commonly:

A few examples of Old Kingdom [...] statuary present some adult males — usually priests, functionaries, or low-status workers — as having undergone a vertical slit on the dorsal aspect of the prepuce, although no flesh has been removed.[61]

It may be performed as a part of traditional customs, such as those in the Pacific Islands and the Philippines. In the medical field, it may be performed for as an alternative to circumcision when circumcision is undesired or impractical. It remains a rare surgery and practice overall.

References

- "Female Genital Mutilation Forbidden in Islam". 2020-05-23.

- "The Islamic Ruling Regarding Female Genital Modification". 2020-05-23.

- Neluis T., Armstrong M. L., Young C., Roberts A. E., Hogan L., Rinard K. (2014). "Prevalence and implications of genital tattoos: A site not forgotten". British Journal of Medical Practitioners. 7 (4).CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Penises, Piercings and Pleasure". 2009-07-23.

- Angulo J. C., García-Díez M., Martínez M. (2011). "Phallic decoration in paleolithic art: genital scarification, piercing and tattoos". The Journal of Urology. 186 (6): 2498–2503. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.077. PMID 22019163.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Schnittiger Trend? Scarification statt Tattoo – Stylight

- Cutting Tattoos: Ziernarben statt Tinte – Erdbeerlounge

- Cuypere G.; T'Sjoen G.; Beerten R.; Selvaggi G.; Sutter P.; Hoebeke P.; Monstrey S.; Vansteenwegen A.; Rubens R. (2005). "Sexual and physical health after sex reassignment surgery". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 34 (6): 679–690. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-7926-5. PMID 16362252. S2CID 42916543.

- Nanda, Serena (1999). Neither Man nor Woman: the Hijras of India (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 9780534509033.

- ISNA's Amicus Brief on Intersex Genital Surgery The Intersex Society of North America, Dated February 7, 1998

- Karen S Vogt, MD, Michael J Bourgeois, MD, Arlan L Rosenbloom, MD, Mary L Windle, PharmD, George. P Chrousos, MD, FAAP, MACP, MACE, FRCP, Merrily P M Poth, MD, Stephen Kemp, MD, PhD Microphallus: Epidemiology Medscape, Updated August 3, 2011

- "What's ISNA's position on surgery?". Intersex Society of North America.

- Gearhart JP, Rock JA (1989). "Total ablation of the penis after circumcision with electrocautery: a method of management and long-term followup". J Urol. 142 (3): 799–801. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38893-6. PMID 2769863.

- "David Reimer, 38, Subject of the John/Joan Case" The New York Times, New York, US, Published May 12, 2004

- "Family Is Awarded $850,000 For Circumcision Accident" The New York Times, New York, US, Published November 2, 1975

- Charles Seabrook. $22.8 million in botched circumcision. Atlanta Constitution, Tuesday, March 12, 1991.

- "End of the line for sex-change doctor | Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". dna. 8 April 2009.

- "CB-CID instructs probe into begging rackets – Times of India". The Times of India.

- "CBCID to seek custody of Kadapa doctor". The Hindu. 8 April 2009.

- Kroll, David. "Penis Reduction Surgery Is No Laughing Matter". Forbes.

- Eichert, David (2019). "'Homosexualization' Revisited: An Audience-Focused Theorization of Wartime Male Sexual Violence". International Feminist Journal of Politics. 21 (3): 409–433. doi:10.1080/14616742.2018.1522264. S2CID 150313647.

- "Prevalence of FGM/C". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Definition of the World Health Organization

- UNICEF 2013, p. 22: "More than 125 million girls and women alive today have been cut in the 29 countries in Africa and the Middle East where FGM/C is concentrated.

UNICEF 2013, p. 121, n. 62: "This estimate [125 million] is derived from weighted averages of FGM/C prevalence among girls aged 0 to 14 and girls and women aged 15 to 49, using the most recently available DHS, MICS and SHHS data (1997–2012) for the 29 countries where FGM/C is concentrated. The number of girls and women who have been cut was calculated using 2011 demographic figures produced by the UN Population Division ... The number of cut women aged 50 and older is based on FGM/C prevalence in women aged 45 to 49."

- P. Stanley Yoder, Shane Khan, "Numbers of women circumcised in Africa: The Production of a Total", USAID, DHS Working Papers, No. 39, March 2008, pp. 13–14: "Infibulation is practiced largely in countries located in northeastern Africa: Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan. Survey data are available for Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Djibouti. Sudan alone accounts for about 3.5 million of the women. ... [T]he estimate of the total number of women infibulated in [Djibouti, Somalia, Eritrea, northern Sudan, Ethiopia, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Chad, Nigeria, Cameroon and Tanzania, for women 15–49 years old] comes to 8,245,449, or just over eight million women." Also see Appendix B, Table 2 ("Types of FGC"), p. 19.

UNICEF 2013, p. 182, identifies "sewn closed" as most common in Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia for 15–49 age group (survey in 2000 for Sudan was not included), and for daughters, Djibouti, Eritrea, Niger and Somalia. UNICEF statistical profiles on FGM, showing type of FGM: Djibouti Archived 2014-10-30 at the Wayback Machine (December 2013), Eritrea Archived 2014-10-30 at the Wayback Machine (July 2014), Somalia Archived October 30, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (December 2013).

Gerry Mackie, "Ending Footbinding and Infibulation: A Convention Account", American Sociological Review, 61(6), December 1996 (pp. 999–1017), p. 1002: "Infibulation, the harshest practice, occurs contiguously in Egyptian Nubia, the Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia, also known as Islamic Northeast Africa."

- "Full list". Treaty Office.

- United Nations General Assembly. "A/RES/48/104 – Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women – UN Documents: Gathering a body of global agreements". www.un-documents.net.

- nthWORD Magazine. "nthWORD Magazine Interview with Liz Canner, filmmaker of Orgasm, Inc". Nthword.com. Archived from the original on 2010-07-14. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- , "Rwandan Women View The Elongation Of Their Labia As Positive", retrieved on 2008-06-18

- , "Enlarging Your Labia", retrieved on 2008-06-22

- , "Sexual health—a new focus for WHO", page 6, retrieved on 2008-06-19

- Bourke, Emily (2009-11-12). "Designer vagina craze worries doctors". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- Liao, Lih Mei; Sarah M Creighton (2007-05-26). "Requests for cosmetic genitoplasty: how should healthcare providers respond?". BMJ. 334 (7603): 1090–1092. doi:10.1136/bmj.39206.422269.BE. PMC 1877941. PMID 17525451.

- The Perfect Vagina Documentary Archived 2011-05-16 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- Green Fiona (2005). "From clitoridectomies to 'designer vaginas': The medical construction of heteronormative female bodies and sexuality through female genital cutting". Sexualities, Evolution & Gender. 7 (2): 153–187. doi:10.1080/14616660500200223.

- Essen B, Johnsdotter S (2004). "Female Genital Mutilation in the West: Traditional Circumcision versus Genital Cosmetic Surgery". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 83 (7): 611–613. doi:10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00590.x. PMID 15225183. S2CID 44583626.

- Braun Virginia (2005). "In search of (better) sexual pleasure: female genital 'cosmetic' surgery". Sexualities. 8 (4): 407–424. doi:10.1177/1363460705056625. S2CID 145795666.

- Davis, Simone Weil. "Designer Vaginas." Women's Voices, Feminist Visions. Ed. Susan Shaw and Janet Lee. New York: McGraw Hill (2012): 270–77.

- Rodrigues Sara (2012). "From Vaginal Exception to Exceptional Vagina: The Biopolitics of Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery". Sexualities. 15 (7): 778–94. doi:10.1177/1363460712454073. S2CID 145095068.

- "Male circumcision: Global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- Svoboda, J. S. (2013). "Circumcision of male infants as a human rights violation". Journal of Medical Ethics. 39 (7): 469–474. doi:10.1136/medethics-2012-101229. ISSN 0306-6800. PMID 23698885. S2CID 7461936.

- Dekkers (June 2009). "Routine (non-religious) neonatal circumcision and bodily integrity: a transatlantic dialogue". Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal. 19 (2): 125–46. doi:10.1353/ken.0.0279. PMID 19623819. S2CID 43235291.

- Krill, Aaron J.; Palmer, Lane S.; Palmer, Jeffrey S. (26 December 2011). "Complications of Circumcision". The Scientific World Journal. 11: 2458–2468. doi:10.1100/2011/373829. ISSN 2356-6140. PMC 3253617. PMID 22235177.

- Blank, Susan; Brady, Michael; Buerk, Ellen; Waldemar, Carlo; Diekema, Douglas; Freedman, Andrew; Maxwell, Lynne; Wegner, Steven (31 August 2012). "Circumcision Policy Statement". Pediatrics. 130 (3): 585–586. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1989. ISSN 1098-4275. PMID 22926180. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- https://ugeskriftet.dk/dmj/male-circumcision-does-not-result-inferior-perceived-male-sexual-function-systematic-review

- Jean-Loïc Le Quellec. "Rock Art Research in Southern Africa 2000–2004". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jalmar and Ione Rudner (1971). The hunter and his art: A survey of rock art in Southern Africa. Cape Town: C. Struick.

- D. Schultheiss; J.J. Mattelaer; F.M. Hodges (2003). "Preputial infibulation: from ancient medicine to modern genital piercing". BJU International. 92 (7): 758–763. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.2003.04490.x. PMID 14616462. S2CID 8855134.

- The masturbation taboo and the rise of routine male circumcision: A review of the historiography RRJL Darby – Journal of Social History, 2003

- Murray Gordon (1989). Slavery in the Arab World. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-941533-30-0.

- Nanda, S. "Hijras: An Alternative Sex and Gender Role in India (in Herdt, G. (1996) Third Sex, Third Gender: Beyond Sexual Dimorphism in Culture and History. Zone Books.)

- "Family Is Awarded $850,000 For Circumcision Accident" The New York Times, New York, USA, Published November 2, 1975

- "David Reimer, 38, Subject of the John/Joan Case" The New York Times, New York, USA, Published May 12, 2004

- Charles Seabrook. $22.8 million in botched circumcision. Atlanta Constitution, Tuesday, March 12, 1991

- Schmidt, William E (October 8, 1985). "A Circumcision Method Draws New Concern". The New York Times

- Vincent Lupo. Family gets $2.75 million in wrongful surgery suit. Lake Charles American Press, Wednesday, May 28, 1986.

- Gearhart, JP; Rock, JA (1989). "Total ablation of the penis after circumcision with electrocautery: A method of management and long-term followup". The Journal of Urology. 142 (3): 799–801. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)38893-6. PMID 2769863

- Rijken, D.J. (2014). Description of the problems accompanying the ritual of Ulwaluko. Ulwaluko.co.za. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- "Bobbitt's Amputation Case Similar to a 1907 Account". Orlando Sentinel. San Jose Mercury News. 30 November 1993. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- "Meatotomy – BME Encyclopedia". wiki.bme.com. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Hodges, Frederick M. (2001). "The Ideal Prepuce in Ancient Greece and Rome: Male Genital Aesthetics and Their Relation to Lipodermos, Circumcision, Foreskin Restoration, and the Kynodesme" (PDF). The Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 75 (Fall 2001): 375–405. doi:10.1353/bhm.2001.0119. PMID 11568485. S2CID 29580193. Retrieved 2018-02-06. Hodges draws a strong distinction between the kynodesme and infibulation "Tethering the akroposthion with the kynodesme is frequently confused with preputial infibulation, which had different objectives and was achieved by surgically piercing the prepuce and using the holes so created for the insertion of a metal clasp (fibula) in order to fasten the prepuce shut."

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Genital modification. |