Saturnalia

Saturnalia was an ancient Roman festival and holiday in honour of the god Saturn, held on 17 December of the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities through to 23 December. The holiday was celebrated with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn, in the Roman Forum, and a public banquet, followed by private gift-giving, continual partying, and a carnival atmosphere that overturned Roman social norms: gambling was permitted, and masters provided table service for their slaves as it was seen as a time of liberty for both slaves and freedmen alike.[1] A common custom was the election of a "King of the Saturnalia", who would give orders to people, which were to be followed and preside over the merrymaking. The gifts exchanged were usually gag gifts or small figurines made of wax or pottery known as sigillaria. The poet Catullus called it "the best of days".[2]

| Saturnalia | |

|---|---|

Saturnalia (1783) by Antoine Callet, showing his interpretation of what the Saturnalia might have looked like | |

| Observed by | Romans |

| Type | Classical Roman religion |

| Significance | Public festival |

| Celebrations | Feasting, role reversals, gift-giving, gambling |

| Observances | Public sacrifice and banquet for the god Saturn; universal wearing of the Pileus |

| Date | 17–23 December |

Saturnalia was the Roman equivalent to the earlier Greek holiday of Kronia, which was celebrated during the Attic month of Hekatombaion in late midsummer. It held theological importance for some Romans, who saw it as a restoration of the ancient Golden Age, when the world was ruled by Saturn. The Neoplatonist philosopher Porphyry interpreted the freedom associated with Saturnalia as symbolizing the "freeing of souls into immortality". Saturnalia may have influenced some of the customs associated with later celebrations in western Europe occurring in midwinter, particularly traditions associated with Christmas, the Feast of the Holy Innocents, and Epiphany. In particular, the historical western European Christmas custom of electing a "Lord of Misrule" may have its roots in Saturnalia celebrations.

Origins

In Roman mythology, Saturn was an agricultural deity who was said to have reigned over the world in the Golden Age, when humans enjoyed the spontaneous bounty of the earth without labour in a state of innocence. The revelries of Saturnalia were supposed to reflect the conditions of the lost mythical age. The Greek equivalent was the Kronia,[3] which was celebrated on the twelfth day of the month of Hekatombaion,[4][3] which occurred from around mid-July to mid-August on the Attic calendar.[3][4] The Greek writer Athenaeus also cites numerous other examples of similar festivals celebrated throughout the Greco-Roman world,[5] including the Cretan festival of Hermaia in honor of Hermes, an unnamed festival from Troezen in honor of Poseidon, the Thessalian festival of Peloria in honor of Zeus Pelorios, and an unnamed festival from Babylon.[5] He also mentions that the custom of masters dining with their slaves was associated with the Athenian festival of Anthesteria and the Spartan festival of Hyacinthia.[5] The Argive festival of Hybristica, though not directly related to the Saturnalia, involved a similar reversal of roles in which women would dress as men and men would dress as women.[5]

The ancient Roman historian Justinus credits Saturn with being a historical king of the pre-Roman inhabitants of Italy:

The first inhabitants of Italy were the Aborigines, whose king, Saturnus, is said to have been a man of such extraordinary justice, that no one was a slave in his reign, or had any private property, but all things were common to all, and undivided, as one estate for the use of every one; in memory of which way of life, it has been ordered that at the Saturnalia slaves should everywhere sit down with their masters at the entertainments, the rank of all being made equal."

.JPG.webp)

Although probably the best-known Roman holiday, Saturnalia as a whole is not described from beginning to end in any single ancient source. Modern understanding of the festival is pieced together from several accounts dealing with various aspects.[7] The Saturnalia was the dramatic setting of the multivolume work of that name by Macrobius, a Latin writer from late antiquity who is the major source for information about the holiday. Macrobius describes the reign of Justinus' "king Saturn" as "a time of great happiness, both on account of the universal plenty that prevailed and because as yet there was no division into bond and free – as one may gather from the complete license enjoyed by slaves at the Saturnalia."[8] In Lucian's Saturnalia it is Chronos himself who proclaims a "festive season, when 'tis lawful to be drunken, and slaves have license to revile their lords".[9]

In one of the interpretations in Macrobius's work, Saturnalia is a festival of light leading to the winter solstice, with the abundant presence of candles symbolizing the quest for knowledge and truth.[10] The renewal of light and the coming of the new year was celebrated in the later Roman Empire at the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, the "Birthday of the Unconquerable Sun", on 23 December.[11]

The popularity of Saturnalia continued into the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, and as the Roman Empire came under Christian rule, many of its customs were recast into or at least influenced the seasonal celebrations surrounding Christmas and the New Year.[12][13][14][15]

Historical context

Saturnalia underwent a major reform in 217 BC, after the Battle of Lake Trasimene, when the Romans suffered one of their most crushing defeats by Carthage during the Second Punic War. Until that time, they had celebrated the holiday according to Roman custom (more Romano). It was after a consultation of the Sibylline books that they adopted "Greek rite", introducing sacrifices carried out in the Greek manner, the public banquet, and the continual shouts of io Saturnalia that became characteristic of the celebration.[16] Cato the Elder (234–149 BC) remembered a time before the so-called "Greek" elements had been added to the Roman Saturnalia.[17]

It was not unusual for the Romans to offer cult (cultus) to the deities of other nations in the hope of redirecting their favour (see evocatio), and the Second Punic War in particular created pressures on Roman society that led to a number of religious innovations and reforms.[18] Robert Palmer has argued that the introduction of new rites at this time was in part an effort to appease Ba'al Hammon, the Carthaginian god who was regarded as the counterpart of the Roman Saturn and Greek Cronus.[19] The table service that masters offered their slaves thus would have extended to Carthaginian or African war captives.[20]

Public religious observance

Rite at the temple of Saturn

The statue of Saturn at his main temple normally had its feet bound in wool, which was removed for the holiday as an act of liberation.[23][24] The official rituals were carried out according to "Greek rite" (ritus graecus). The sacrifice was officiated by a priest,[25] whose head was uncovered; in Roman rite, priests sacrificed capite velato, with head covered by a special fold of the toga.[26] This procedure is usually explained by Saturn's assimilation with his Greek counterpart Cronus, since the Romans often adopted and reinterpreted Greek myths, iconography, and even religious practices for their own deities, but the uncovering of the priest's head may also be one of the Saturnalian reversals, the opposite of what was normal.[27]

Following the sacrifice the Roman Senate arranged a lectisternium, a ritual of Greek origin that typically involved placing a deity's image on a sumptuous couch, as if he were present and actively participating in the festivities. A public banquet followed (convivium publicum).[28][29]

The day was supposed to be a holiday from all forms of work. Schools were closed, and exercise regimens were suspended. Courts were not in session, so no justice was administered, and no declaration of war could be made.[30] After the public rituals, observances continued at home.[31] On 18 and 19 December, which were also holidays from public business, families conducted domestic rituals. They bathed early, and those with means sacrificed a suckling pig, a traditional offering to an earth deity.[32]

Human offerings

Saturn also had a less benevolent aspect. One of his consorts was Lua, sometimes called Lua Saturni ("Saturn's Lua") and identified with Lua Mater, "Mother Destruction", a goddess in whose honor the weapons of enemies killed in war were burned, perhaps in expiation.[35] Saturn's chthonic nature connected him to the underworld and its ruler Dis Pater, the Roman equivalent of Greek Plouton (Pluto in Latin) who was also a god of hidden wealth.[36] In sources of the third century AD and later, Saturn is recorded as receiving dead gladiators as offerings (munera) during or near the Saturnalia.[37] These gladiatorial events, ten days in all throughout December, were presented mainly by the quaestors and sponsored with funds from the treasury of Saturn.[38]

The practice of gladiator munera was criticized by Christian apologists as a form of human sacrifice.[39][40] Although there is no evidence of this practice during the Republic, the offering of gladiators led to later theories that the primeval Saturn had demanded human victims. Macrobius says that Dis Pater was placated with human heads and Saturn with sacrificial victims consisting of men (virorum victimis).[41][40] During the visit of Hercules to Italy, the civilizing demigod insisted that the practice be halted and the ritual reinterpreted. Instead of heads to Dis Pater, the Romans were to offer effigies or masks (oscilla); a mask appears in the representation of Saturnalia in the Calendar of Filocalus. Since the Greek word phota meant both 'man' and 'lights', candles were a substitute offering to Saturn for the light of life.[33][34] The figurines that were exchanged as gifts (sigillaria) may also have represented token substitutes.[42]

Private festivities

Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.24.22–23

Role reversal

Saturnalia was characterized by role reversals and behavioral license.[5] Slaves were treated to a banquet of the kind usually enjoyed by their masters.[5] Ancient sources differ on the circumstances: some suggest that master and slave dined together,[44] while others indicate that the slaves feasted first, or that the masters actually served the food. The practice might have varied over time.[7]

Saturnalian license also permitted slaves to disrespect their masters without the threat of a punishment. It was a time for free speech: the Augustan poet Horace calls it "December liberty".[45] In two satires set during the Saturnalia, Horace has a slave offer sharp criticism to his master.[46] Everyone knew, however, that the leveling of the social hierarchy was temporary and had limits; no social norms were ultimately threatened, because the holiday would end.[47]

The toga, the characteristic garment of the male Roman citizen, was set aside in favor of the Greek synthesis, colourful "dinner clothes" otherwise considered in poor taste for daytime wear.[48] Romans of citizen status normally went about bare-headed, but for the Saturnalia donned the pilleus, the conical felt cap that was the usual mark of a freedman. Slaves, who ordinarily were not entitled to wear the pilleus, wore it as well, so that everyone was "pilleated" without distinction.[49][50]

The participation of freeborn Roman women is implied by sources that name gifts for women, but their presence at banquets may have depended on the custom of their time; from the late Republic onward, women mingled socially with men more freely than they had in earlier times. Female entertainers were certainly present at some otherwise all-male gatherings.[51] Role-playing was implicit in the Saturnalia's status reversals, and there are hints of mask-wearing or "guising".[52][53] No theatrical events are mentioned in connection with the festivities, but the classicist Erich Segal saw Roman comedy, with its cast of impudent, free-wheeling slaves and libertine seniors, as imbued with the Saturnalian spirit.[54]

Gambling

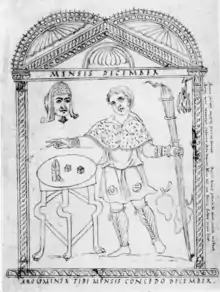

Gambling and dice-playing, normally prohibited or at least frowned upon, were permitted for all, even slaves. Coins and nuts were the stakes. On the Calendar of Philocalus, the Saturnalia is represented by a man wearing a fur-trimmed coat next to a table with dice, and a caption reading: "Now you have license, slave, to game with your master."[55][56] Rampant overeating and drunkenness became the rule, and a sober person the exception.[57]

Seneca looked forward to the holiday, if somewhat tentatively, in a letter to a friend:

"It is now the month of December, when the greatest part of the city is in a bustle. Loose reins are given to public dissipation; everywhere you may hear the sound of great preparations, as if there were some real difference between the days devoted to Saturn and those for transacting business. … Were you here, I would willingly confer with you as to the plan of our conduct; whether we should eve in our usual way, or, to avoid singularity, both take a better supper and throw off the toga."[58]

Some Romans found it all a bit much. Pliny describes a secluded suite of rooms in his Laurentine villa, which he used as a retreat: "...especially during the Saturnalia when the rest of the house is noisy with the licence of the holiday and festive cries. This way I don't hamper the games of my people and they don't hinder my work or studies."[59]

Gift-giving

The Sigillaria on 19 December was a day of gift-giving.[60] Because gifts of value would mark social status contrary to the spirit of the season, these were often the pottery or wax figurines called sigillaria made specially for the day, candles, or "gag gifts", of which Augustus was particularly fond.[61] Children received toys as gifts.[62] In his many poems about the Saturnalia, Martial names both expensive and quite cheap gifts, including writing tablets, dice, knucklebones, moneyboxes, combs, toothpicks, a hat, a hunting knife, an axe, various lamps, balls, perfumes, pipes, a pig, a sausage, a parrot, tables, cups, spoons, items of clothing, statues, masks, books, and pets.[63] Gifts might be as costly as a slave or exotic animal,[64] but Martial suggests that token gifts of low intrinsic value inversely measure the high quality of a friendship.[65] Patrons or "bosses" might pass along a gratuity (sigillaricium) to their poorer clients or dependents to help them buy gifts. Some emperors were noted for their devoted observance of the Sigillaria.[66]

In a practice that might be compared to modern greeting cards, verses sometimes accompanied the gifts. Martial has a collection of poems written as if to be attached to gifts.[67][68] Catullus received a book of bad poems by "the worst poet of all time" as a joke from a friend.[69]

Gift-giving was not confined to the day of the Sigillaria. In some households, guests and family members received gifts after the feast in which slaves had shared.[50]

King of the Saturnalia

Imperial sources refer to a Saturnalicius princeps ("Ruler of the Saturnalia"), who ruled as master of ceremonies for the proceedings. He was appointed by lot, and has been compared to the medieval Lord of Misrule at the Feast of Fools. His capricious commands, such as "Sing naked!" or "Throw him into cold water!", had to be obeyed by the other guests at the convivium: he creates and (mis)rules a chaotic and absurd world. The future emperor Nero is recorded as playing the role in his youth.[71]

Since this figure does not appear in accounts from the Republican period, the princeps of the Saturnalia may have developed as a satiric response to the new era of rule by a princeps, the title assumed by the first emperor Augustus to avoid the hated connotations of the word "king" (rex). Art and literature under Augustus celebrated his reign as a new Golden Age, but the Saturnalia makes a mockery of a world in which law is determined by one man and the traditional social and political networks are reduced to the power of the emperor over his subjects.[72] In a poem about a lavish Saturnalia under Domitian, Statius makes it clear that the emperor, like Jupiter, still reigns during the temporary return of Saturn.[73]

Io Saturnalia

The phrase io Saturnalia was the characteristic shout or salutation of the festival, originally commencing after the public banquet on the single day of 17 December.[29][21] The interjection io (Greek ἰώ, ǐō) is pronounced either with two syllables (a short i and a long o) or as a single syllable (with the i becoming the Latin consonantal j and pronounced yō). It was a strongly emotive ritual exclamation or invocation, used for instance in announcing triumph or celebrating Bacchus, but also to punctuate a joke.[74]

On the calendar

As an observance of state religion, Saturnalia was supposed to have been held ante diem xvi Kalendas Ianuarias, sixteen days before the Kalends of January, on the oldest Roman religious calendar,[75] which the Romans believed to have been established by the legendary founder Romulus and his successor Numa Pompilius. It was a dies festus, a legal holiday when no public business could be conducted.[21][76] The day marked the dedication anniversary (dies natalis) of the Temple to Saturn in the Roman Forum in 497 BC.[21][22] When Julius Caesar had the calendar reformed because it had fallen out of synchronization with the solar year, two days were added to the month, and Saturnalia fell on 17 December. It was felt, however, that the original day had thus been moved by two days, and so Saturnalia was celebrated under Augustus as a three-day official holiday encompassing both dates.[77]

By the late Republic, the private festivities of Saturnalia had expanded to seven days,[78][40] but during the Imperial period contracted variously to three to five days.[79] Caligula extended official observances to five.[80]

The date 17 December was the first day of the astrological sign Capricorn, the house of Saturn, the planet named for the god.[81] Its proximity to the winter solstice (21 to 23 December on the Julian calendar) was endowed with various meanings by both ancient and modern scholars: for instance, the widespread use of wax candles (cerei, singular cereus) could refer to "the returning power of the sun's light after the solstice".[82]

Ancient theological and philosophical views

Roman

The Saturnalia reflects the contradictory nature of the deity Saturn himself: "There are joyful and utopian aspects of careless well-being side by side with disquieting elements of threat and danger."[68]

As a deity of agricultural bounty, Saturn embodied prosperity and wealth in general. The name of his consort Ops meant "wealth, resources". Her festival, Opalia, was celebrated on 19 December. The Temple of Saturn housed the state treasury (aerarium Saturni) and was the administrative headquarters of the quaestors, the public officials whose duties included oversight of the mint. It was among the oldest cult sites in Rome, and had been the location of "a very ancient" altar (ara) even before the building of the first temple in 497 BC.[84][85]

The Romans regarded Saturn as the original and autochthonous ruler of the Capitolium,[86] and the first king of Latium or even the whole of Italy.[87] At the same time, there was a tradition that Saturn had been an immigrant deity, received by Janus after he was usurped by his son Jupiter (Zeus) and expelled from Greece.[88] His contradictions—a foreigner with one of Rome's oldest sanctuaries, and a god of liberation who is kept in fetters most of the year—indicate Saturn's capacity for obliterating social distinctions.[89]

Roman mythology of the Golden Age of Saturn's reign differed from the Greek tradition. He arrived in Italy "dethroned and fugitive",[90] but brought agriculture and civilization and became a king. As the Augustan poet Virgil described it:

"[H]e gathered together the unruly race [of fauns and nymphs] scattered over mountain heights, and gave them laws … . Under his reign were the golden ages men tell of: in such perfect peace he ruled the nations."[91]

The third century Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry took an allegorical view of the Saturnalia. He saw the festival's theme of liberation and dissolution as representing the "freeing of souls into immortality"—an interpretation that Mithraists may also have followed, since they included many slaves and freedmen.[92] According to Porphyry, the Saturnalia occurred near the winter solstice because the sun enters Capricorn, the astrological house of Saturn, at that time.[93] In the Saturnalia of Macrobius, the proximity of the Saturnalia to the winter solstice leads to an exposition of solar monotheism, the belief that the Sun (see Sol Invictus) ultimately encompasses all divinities as one.[94]

Jewish

The Mishna and Talmud (Avodah Zara 8a) describe a pagan festival called Saturnura which occurs for eight days before the winter solstice. It is followed for eight days after the solstice with a festival called Kalenda culminating with the Kalends of January. The Talmud ascribes the origins of this festival to Adam, who saw that the days were getting shorter and thought it was punishment for his sin. He was afraid that the world was returning to the chaos and emptiness that existed before creation. He sat and fasted for eight days. Once he saw that the days were getting longer again he realized that this was the natural cycle of the world, so made eight days of celebration. The Talmud states that this festival was later turned into a pagan festival. Later on in the page, the Talmud calls it Saturnalia. [95][96] See Christmas - Talmudic hypothesis.

Influence

Unlike several Roman religious festivals which were particular to cult sites in the city, the prolonged seasonal celebration of Saturnalia at home could be held anywhere in the Empire.[97] Saturnalia continued as a secular celebration long after it was removed from the official calendar.[98] As William Warde Fowler notes: "[Saturnalia] has left its traces and found its parallels in great numbers of medieval and modern customs, occurring about the time of the winter solstice."[99]

The actual date of Jesus's birth is unknown,[100][101] but, in the fourth century AD, Pope Julius I (337–352) formalized that it should be celebrated on 25 December,[102][103] around the same time as the Saturnalia celebrations.[100][104] Some have speculated that part of the reason why he chose this date may have been because he was trying to create a Christian alternative to Saturnalia.[100] Another reason for the decision may have been because, in 274 AD, the Roman emperor Aurelian had declared 25 December the birthdate of Sol Invictus[101] and Julius I may have thought that he could attract more converts to Christianity by allowing them to continue to celebrate on the same day.[101] He may have also been influenced by the idea that Jesus had died on the anniversary of his conception;[101] because Jesus died during Passover and, in the third century AD, Passover was celebrated on 25 March,[101] he may have assumed that Jesus's birthday must have come nine months later, on 25 December.[101]

_-_Twelfth-night_(The_King_Drinks)_-_WGA22083.jpg.webp)

As a result of the close proximity of dates, many Christians in western Europe continued to celebrate traditional Saturnalia customs in association with Christmas and the surrounding holidays.[100][105][14] Like Saturnalia, Christmas during the Middle Ages was a time of ruckus, drinking, gambling, and overeating.[14] The tradition of the Saturnalicius princeps was particularly influential.[105][14] In medieval France and Switzerland, a boy would be elected "bishop for a day" on 28 December (the Feast of the Holy Innocents)[105][14] and would issue decrees much like the Saturnalicius princeps.[105][14] The boy bishop's tenure ended during the evening vespers.[106] This custom was common across western Europe, but varied considerably by region;[106] in some places, the boy bishop's orders could become quite rowdy and unrestrained,[106] but, in others, his power was only ceremonial.[106] In some parts of France, during the boy bishop's tenure, the actual clergy would wear masks or dress in women's clothing, a reversal of roles in line with the traditional character of Saturnalia.[14]

During the late medieval period and early Renaissance, many towns in England elected a "Lord of Misrule" at Christmas time to preside over the Feast of Fools.[105][14] This custom was sometimes associated with the Twelfth Night or Epiphany.[107] A common tradition in western Europe was to drop a bean, coin, or other small token into a cake or pudding;[105] whoever found the object would become the "King (or Queen) of the Bean".[105] During the Protestant Reformation, reformers sought to revise or even completely abolish such practices, which they regarded as "popish";[14] these efforts were largely successful and, in many places, these customs died out completely.[14][108] The Puritans banned the "Lord of Misrule" in England[108] and the custom was largely forgotten shortly thereafter, though the bean in the pudding survived as a tradition of a small gift to the one finding a single almond hidden in the traditional Christmas porridge in Scandinavia.[108][109]

Nonetheless, in the middle of the nineteenth century, some of the old ceremonies, such as gift-giving, were revived in English-speaking countries as part of a widespread "Christmas revival".[14][108][110] During this revival, authors such as Charles Dickens sought to reform the "conscience of Christmas" and turn the formerly riotous holiday into a family-friendly occasion.[110] Vestiges of the Saturnalia festivities may still be preserved in some of the traditions now associated with Christmas.[14][111] The custom of gift-giving at Christmas time resembles the Roman tradition of giving sigillaria[111] and the lighting of Advent candles resembles the Roman tradition of lighting torches and wax tapers.[111][105] Likewise, Saturnalia and Christmas both share associations with eating, drinking, singing, and dancing.[111][105]

See also

References

- Miller, John F. "Roman Festivals," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 172.

- Catullus 14.15 (optimo dierum), as cited by Mueller 2010, p. 221

- Hansen, William F. (2002). Ariadne's Thread: A Guide to International Tales Found in Classical Literature. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 385. ISBN 978-0801475726.

- Bremmer, Jan M. (2008). Greek Religion and Culture, the Bible and the Ancient Near East. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. p. 82. ISBN 978-9004164734.

- Parker, Robert (2011). On Greek Religion. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-8014-7735-5.

- Smith, Andrew. "Justinus: Epitome of Pompeius Trogus (7)". www.attalus.org. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- Dolansky 2011, p. 484.

- Standhartinger, Angela. Saturnalia in Greco-Roman Culture. p. 184.

- Roth, Marty. Drunk the Night Before: An Anatomy of Intoxication. University of Minnesota Press.

- Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.1.8–9; Jane Chance, Medieval Mythography: From Roman North Africa to the School of Chartres, A.D. 433–1177 (University Press of Florida, 1994), p. 71.

- Robert A. Kaster, Macrobius: Saturnalia, Books 1–2 (Loeb Classical Library, 2011), note on p. 16.

- Beard, North & Price 2004, p. 259.

- Williams, Craig A., Martial: Epigrams Book Two (Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 259 (on the custom of gift-giving). Many observers schooled in the classical tradition have noted similarities between the Saturnalia and historical revelry during the Twelve Days of Christmas and the Feast of Fools

- Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W.; Settis, Salvatore (2010). "Bacchanalia and Saturnalia". The Classical Tradition. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-674-03572-0.

- "The reciprocal influences of the Saturnalia, Germanic solstitial festivals, Christmas, and Chanukkah are familiar," notes C. Bennet Pascal, "October Horse," Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 85 (1981), p. 289.

- Livy 22.1.20; Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.10.18 (on the shout); Palmer 1997, pp. 63–64

- Palmer 1997, p. 64, citing the implications of Cato, frg. 77 ORF4.

- Palmer 1997, p. passim See also the importation of Cybele to Rome during this time.

- Palmer 1997, p. 64 For other scholars who have held this view, including those who precede Palmer, see Versnel 1992, pp. 141–142, especially note 32.

- Palmer 1997, pp. 63–64.

- Palmer 1997, p. 63.

- Mueller 2010, p. 221.

- Macrobius 1.8.5, citing Verrius Flaccus as his authority; see also Statius, Silvae 1.6.4; Arnobius 4.24; Minucius Felix 23.5; Miller, "Roman Festivals," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 172

- Versnel 1992, p. 142.

- The identity or title of this priest is unknown; perhaps the rex sacrorum or one of the magistrates: William Warde Fowler, The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic (London, 1908), p. 271.

- Versnel 1992, pp. 139–140.

- Versnel 1992, p. 140.

- Livy 22.1; Palmer 1997, p. 63

- Versnel 1992, p. 141.

- Versnel 1992, p. 147, citing Pliny the Younger, Letters 8.7.1, Martial 5.84 and 12.81; Lucian, Cronosolon 13; Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.10.1, 4, 23.

- Beard, North & Price 2004, p. 50.

- Horace, Odes 3.17, Martial 14.70; Fowler, Roman Festivals, p. 272.

- Taylor, Rabun (2005). "Roman Oscilla: An Assessment". RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press. 48 (48): 101. doi:10.1086/RESv48n1ms20167679. JSTOR 20167679. S2CID 193568609.

- Chance, Jane (1994). Medieval Mythography: From Roman North Africa to the School of Chartres, A.D. 433–1177. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. pp. 71–72. ISBN 9780813012568.

- Mueller 2010, p. 222; Versnel, however, proposes that Lua Saturni should not be identified with Lua Mater, but rather refers to "loosening": she represents the liberating function of Saturn Versnel 1992, p. 144

- Versnel 1992, pp. 144–145 See also the Etruscan god Satre.

- For instance, Ausonius, Eclogue 23 and De feriis Romanis 33–7. See Versnel 1992, pp. 146 and 211–212 and Thomas E.J. Wiedemann, Emperors and Gladiators (Routledge, 1992, 1995), p. 47.

- More precisely, eight days were subsidized from the Imperial treasury (arca fisci) and two mostly by the sponsoring magistrate. Salzmann, Michele Renee, On Roman Time: The Codex-Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity (University of California Press, 1990), p. 186.

- Mueller 2010, p. 222.

- Versnel 1992, p. 146.

- Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.7.31

- Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.10.24; Carlin A. Barton, The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster (Princeton University Press, 1993), p. 166. For another Roman ritual that may represent human sacrifice, see Argei. Oscilla were also part of the Latin Festival and the Compitalia: Fowler, Roman Festivals, p. 272.

- Beard, North & Price 2004, p. 124.

- Seneca, Epistulae 47.14; Carlin A. Barton, The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster (Princeton University Press, 1993), p. 498.

- Horace, Satires 2.7.4, libertas Decembri; Mueller 2010, pp. 221–222

- Horace, Satires, Book 2, poems 3 and 7; Catherine Keane, Figuring Genre in Roman Satire (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 90; Maria Plaza, The Function of Humour in Roman Verse Satire: Laughing and Lying (Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 298–300 et passim.

- Barton, The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans, passim.

- Versnel 1992, p. 147 (especially note 59).

- Versnel 1992, p. 147.

- Dolansky 2011, p. 492.

- Dolansky 2011, pp. 492–494.

- At the beginning of Horace's Satire 2.3, and the mask in the Saturnalia imagery of the Calendar of Philocalus, and Martial's inclusion of masks as Saturnalia gifts

- Beard, North & Price 2004, p. 125.

- Segal, Erich, Roman Laughter: The Comedy of Plautus (Oxford University Press, 1968, 2nd ed. 1987), pp. 8–9, 32–33, 103 et passim.

- Versnel 1992, p. 148 citing Suetonius, Life of Augustus 71; Martial 1.14.7, 5.84, 7.91.2, 11.6, 13.1.7; 14.1; Lucian, Saturnalia 1.

- See a copy of the actual calendar

- Versnel 1992, p. 147, citing Cato the Elder, De agricultura 57; Aulus Gellius 2.24.3; Martial 14.70.1 and 14.1.9; Horace, Satire 2.3.5; Lucian, Saturnalia 13; Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Alexander Severus 37.6.

- Seneca the Younger, Epistulae 18.1–2.

- Pliny the Younger, Letters 2.17.24. Horace similarly sets Satire 2.3 during the Saturnalia but in the countryside, where he has fled the frenzied pace.

- Dolansky 2011, pp. 492, 502 Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.10.24, seems to indicate that the Sigillaria was a market that occurred at the end of Saturnalia, but the Gallo-Roman scholar-poet Ausonius (Eclogues 16.32) refers to it as a religious occasion (sacra sigillorum, "rites of the sigillaria").

- Suetonius, Life of Augustus 75; Versnel 1992, p. 148, pointing to the Cronosolon of Lucian on the problem of unequal gift-giving.

- Beryl Rawson, "Adult-Child Relationships in Ancient Rome," in Marriage, Divorce, and Children in Ancient Rome (Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 19.

- Martial, Epigrams 13 and 14, the Xenia and the Apophoreta, published 84–85 AD.

- Dolansky 2011, p. 492 citing Martial 5.18, 7.53, 14; Suetonius, Life of Augustus 75 and Life of Vespasian 19 on the range of gifts.

- Ruurd R. Nauta, Poetry for Patrons: Literary Communication in the Age of Domitian (Brill, 2002), pp. 78–79.

- Versnel 1992, pp. 148–149, citing Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.10.24 and 1.11.49; Suetonius, Life of Claudius 5; Scriptores Historiae Augustae Hadrian 17.3, Caracalla 1.8 and Aurelian 50.3. See also Dolansky 2011, p. 492

- Martial, Book 14 (Apophoreta); Williams, Martial: Epigrams, p. 259; Nauta, Poetry for Patrons, p. 79 et passim.

- Versnel 1992, p. 148.

- Catullus, Carmen 14; Robinson Ellis, A Commentary on Catullus (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1876), pp. 38–39.

- The painting represents a scene recorded by Josephus, Antiquitates Iudiacae 19; and Cassius Dio 60.1.3.

- By Tacitus, Annales 13.15.

- Versnel 1992, pp. 206–208.

- Statius, Silvae 1.6; Nauta, Poetry for Patrons, p. 400.

- Entry on io, Oxford Latin Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982, 1985 reprinting), p. 963.

- Palmer 1997, p. 62.

- Beard, North & Price 2004, p. 6.

- Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.10.23; Mueller 2010, p. 221; Fowler, Roman Festivals, p. 268; Carole E. Newlands, "The Emperor's Saturnalia: Statius, Silvae 1.6," in Flavian Rome: Culture, Image, Text (Brill, 2003), p. 505.

- Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.10.3, citing the Atellane composers Novius and Mummius

- Miller, "Roman Festivals," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 172.

- Suetonius, Life of Caligula 17; Cassius Dio 59.6.4; Mueller 2010, p. 221; Fowler, Roman Festivals, p. 268, citing Mommsen and CIL I.337.

- Fowler, Roman Festivals, p. 268, note 3; Roger Beck, "Ritual, Myth, Doctrine, and Initiation in the Mysteries of Mithras: New Evidence from a Cult Vessel," Journal of Roman Studies 90 (2000), p. 179.

- Fowler, Roman Festivals, p. 272. Fowler thought the use of candles influenced the Christmas rituals of the Latin Church, and compared the symbolism of the candles to the Yule log.

- Versnel 1992, p. 162.

- Versnel 1992, pp. 136–137.

- Fowler, Roman Festivals, p. 271.

- The Capitolium had thus been called the Mons Saturnius in older times.

- Versnel 1992, pp. 138–139.

- Versnel 1992, p. 139 The Roman theologian Varro listed Saturn among the Sabine gods.

- Versnel 1992, pp. 139, 142–143.

- Versnel, "Saturnus and the Saturnalia," p. 143.

- Virgil, Aeneid 8. 320–325, as cited by Versnel 1992, p. 143

- Porphyry, De antro 23, following Numenius, as cited by Roger Beck, "Qui Mortalitatis Causa Convenerunt: The Meeting of the Virunum Mithraists on June 26, A.D. 184," Phoenix 52 (1998), p. 340. One of the speakers in Macrobius's Saturnalia is Vettius Agorius Praetextatus, a Mithraist.

- Beck, Roger, "Ritual, Myth, Doctrine, and Initiation in the Mysteries of Mithras: New Evidence from a Cult Vessel," Journal of Roman Studies 90 (2000), p. 179.

- van den Broek, Roel, "The Sarapis Oracle in Macrobius Sat., I, 20, 16–17," in Hommages à Maarten J. Vermaseren (Brill, 1978), vol. 1, p. 123ff.

- A portion of Avodah Zarah 8, quoted in Menachem Leibtag's Chanuka – Its Biblical Roots – Part Two, hosted on The Tanach Study Center

- A portion of Avodah Zarah 8, quoted in Ebn Leader's The Darkness of Winter – Environmental reflections on Hanukah Archived 2010-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, hosted on The Kibbutz Institute for Holidays and Jewish Culture.

- Woolf, Greg, "Found in Translation: The Religion of the Roman Diaspora," in Ritual Dynamics and Religious Change in the Roman Empire. Proceedings of the Eighth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Heidelberg, July 5–7, 2007) (Brill, 2009), p. 249. See Aulus Gellius 18.2.1 for Romans living in Athens and celebrating the Saturnalia.

- Michele Renee Salzman, "Religious Koine and Religious Dissent," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), p. 121.

- Fowler, Roman Festivals, p. 268.

- John, J. (2005). A Christmas Compendium. New York City, New York and London, England: Continuum. p. 112. ISBN 0-8264-8749-1.

- Struthers, Jane (2012). The Book of Christmas: Everything We Once Knew and Loved about Christmastime. London, England: Ebury Press. pp. 17–21. ISBN 9780091947293.

- Martindale, Cyril (1908). "Christmas". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2018-11-18.

- Patrologiae cursus completus, seu bibliotheca universalis, integra, uniformis, commoda, oeconomica, omnium SS. Patrum, doctorum scriptorumque ecclesiasticorum, sive latinorum, qui ab aevo apostolico ad tempora Innocentii 3. (anno 1216) pro Latinis et Concilii Florentini (ann. 1439) pro Graecis floruerunt: Recusio chronologica ...: Opera quà exstant universa Constantini Magni, Victorini necnon et Nazarii, anonymi, S. Silvestri papà , S. Marci papà , S. Julii papà , Osii Cordubensis, Candidi Ariani, Liberii papà , et Potamii (in Latin). Vrayet. 1844. p. 968.

- "Why is Christmas celebrated on December 25?". www.italyheritage.com. Retrieved 2018-11-18.

- Forbes, Bruce David (2007). Christmas: A Candid History. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-520-25104-5.

- Mackenzie, Neil (2012). The Medieval Boy Bishops. Leicestershire, England: Matadore. pp. 26–29. ISBN 978-1780880-082.

- Shaheen, Naseeb (1999). Biblical References in Shakespeare's Plays. Newark, Maryland: University of Delaware Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-61149-358-0.

- Jeffrey, Yvonne (17 September 2008). The Everything Family Christmas Book. Everything Books. pp. 46–47. ISBN 9781605507835.

- Sjue, K. (25 December 2016). "Historien om mandelen i grøten". Dagbladet. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Rowell, Geoffrey (December 1993). "Dickens and the Construction of Christmas". History Today. 43 (12). Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- Stuttard, David (17 December 2012). "Did the Romans invent Christmas?". bbc.co.uk. British Broadcasting Company.

Bibliography

Ancient sources

Modern secondary sources

- Beard, Mary; North, J. A.; Price, S. R. F. (2004) [1998], Religions of Rome: A Sourcebook, 2, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-45646-0

- Dolansky, Fanny (2011), "Celebrating the Saturnalia: Religious Ritual and Roman Domestic Life", in Rawson, Beryl (ed.), A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds, Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World, Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1405187671

- Mueller, Hans Friedrich (2010), "Saturn", in Gagarin, Michael; Fantham, Elaine (eds.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, pp. 221–222, ISBN 978-0-19-538839-8

- Palmer, Robert E. A. (1997), Rome and Carthage at Peace, Historia – Einzelschriften, Stuttgart, Germany: Franz Steiner, ISBN 978-3515070409

- Versnel, Hank S. (1 December 1992), "Saturnus and the Saturnalia", Inconsistencies in Greek and Roman Religion, Volume 2: Transition and Reversal in Myth and Ritual, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-29673-2

External links

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article about "Saturnalia". |

- Saturnalia - Ancient History Encyclopedia

- Saturnalia, A longer article by James Grout