Saxe-Coburg

Saxe-Coburg (German: Sachsen-Coburg) was a duchy held by the Ernestine branch of the Wettin dynasty in today's Bavaria, Germany.

Duchy of Saxe-Coburg Herzogtum Sachsen-Coburg | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1596–1633 1680–1735 | |||||||||||||

Saxe-Coburg, shown with the other Ernestine duchies | |||||||||||||

| Status | State of the Holy Roman Empire | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Coburg | ||||||||||||

| Government | Principality | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern Europe | ||||||||||||

1572 | |||||||||||||

| 1596 | |||||||||||||

• Fell to S-Eisenach | 1633 | ||||||||||||

1680 | |||||||||||||

1699–1735 | |||||||||||||

| 1735 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

History

Ernestine Line

When Henry IV, Count of Henneberg – Schleusingen, died in 1347, the possessions of the House of Henneberg – Schleusingen were divided between his widow, Jutta of Brandenburg-Salzwedel, and Henry's younger brother, John, and Jutta was given the so-called “neues Herrschaft” ("new lordship"), with Coburg among other properties. The death of Jutta six years later was followed by the division of the new Herrschaft amongst three of her daughters.

The second daughter, Catherine of Henneberg, was awarded the southeastern part of the Coburgish land. After their wedding in 1346, Catherine's husband, Frederick III, the Margrave of Meissen from the House of Wettin, asked for his wife's dowry, the Coburgish land called the Pflege Coburg; but his father-in-law resisted the devolution, and Frederick III could not touch it until after the death of Jutta in 1353.

The Coburgish land was the southernmost part of the Saxon territories. By the Treaty of Leipzig in 1485, the Great Division of the Saxon States (Großen Sächsischen Landesteilung) between the Albertine and Ernestine lines, this Coburgish land, together with the greater part of the Landgraviate of Thuringia and the possessions in the Vogtland, was allotted to Ernest, Elector of Saxony, and thus to the Ernestine side of the House of Wettin.

Duke John Ernest

After losing the Schmalkaldic War in 1547, the Ernestines had their territorial possessions greatly reduced in Thuringia. Because the Districts of the Coburger Land were assigned to Duke John Ernest as “equipment” (Ausstattung), they remained unaffected by the measures against the outlawed Electors. John Ernest settled in the city of Coburg to build the Ehrenburg as his new residential palace, which was later also used and expanded by various Dukes of Saxe-Coburg.[1] When John Ernest died childless in 1553, the former Elector John Frederick I was now only the Duke of Saxony, just released from prison only to die in 1554.

Joint Rule

The Coburger Land was given to Elector John Frederick II “the Middle” as his share of the inheritance. He reigned from Gotha together with his brothers John William, residing in Weimar, and John Frederick III “the Younger”. After the early death of their youngest brother, there was a preliminary division of the Ernestine properties, in which the surviving brothers agreed to have a “Mutschierung”, i. e., a change in government, every three years. John Frederick II reigned in Gotha, Eisenach and Coburg. But he failed in his efforts to regain the rank of the Elector for himself and his House, fell into conflict with the Emperor (Grumbachsche Händel, or “Grumbach Feud”), and was eventually outlawed and imprisoned until his death. His rule initially fell to his brother, John William, who had participated in the Reichsexekution on the side of Augustus, Elector of Saxony, but it was returned, in the Erfurter Teilung (“Erfurter Division”) of 1572, to the sons of John Frederick.

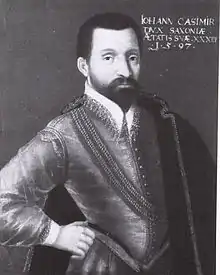

Duke John Casimir

With the Erfurter Division Treaty of 1572 the remaining lands were eventually and forcibly divided between the sons of the defeated John Frederick II. The younger son was John William of Saxe-Weimar, who received, among other properties, the cities of Jena, Altenburg and Saalfeld. Because the elder son, John Frederick II “the Middle” was still in prison for life in Austria, his sons, John Casimir and John Ernest, were given the new Principality of Saxe-Coburg, with Coburg chosen as their residence and “Duke” as their titles. The Principality consisted of the southern and western parts of Thuringia, including the cities of Eisenach, Gotha and Hildburghausen. One of the guardians for the sons was the enemy of their father, Augustus, Elector of Saxony, who supervised their education and who, for his own reasons, began in Coburg a corrupt Regency with Saxon officials from his Electorate.

Only after the death of Elector Augustus of Saxony in 1586 were Duke John Casimir and his brother John Ernest able to take over the government of their Principality. In 1596, the Principality was cut in half to give John Ernest his own Duchy of Saxe-Eisenach and John Casimir remained in Coburg to reign alone. His remaining territories were the Districts of Coburg, with the jurisdictions of Lauter, Rodach and Gestungshausen; Heldburg with the jurisdictions of Hildburghausen, Römhild, Eisfeld, Schalkau, Sonneberg, Neustadt bei Coburg, Neuhaus am Rennweg, and Mönchröden; and Sonnefeld. Under the reign of John Casimir, there was a building boom in Coburg. Above all, he established as the nucleus of Coburger government an administrative apparatus that would survive for a long time after his death and through many wars and political upheavals. Casimir, the founder of the Coburger State, died in 1633. His Principality then fell to his brother, the Duke of Saxe-Eisenach, John Ernest, who was also childless. During this time, the Coburger Land was hit hard by the Thirty Years War as the staging area for numerous armies. The population fell from 55,000 to 22,000.

Inheritance

In 1638, the Ernestine line of Saxe-Eisenach died out and its territories were divided between the Duchies of Saxe-Weimar and Saxe-Altenburg. By drawing lots, the Coburger Land fell in 1640, with the Districts of Coburg, Sonnefeld, Sonneberg, Neuhaus am Rennweg, Neustadt bei Coburg, Hildburghausen and Römhild to Frederick William II of Saxe-Altenburg . The principalities of Altenburg and Coburg were ruled in personal union by the Duke but they maintained their own state authorities. Duke Frederick William II died in 1669, followed three years later by his only son, Hereditary Prince Frederick William III, bringing the line of Saxe-Altenburg to extinction. Three quarters of the Altenburger area, including the Coburger Land, were secured, with the Gotha Division Treaty (Gothaer Teilungsvertrag) of 1672, for the new sovereign, Ernest I “the Pious”, of Saxe-Gotha, who died in 1675. The administration of Saxe-Gotha was undertaken by his eldest son, Frederick I, at the request of his father, together with his six other brothers.

Because the trial of the common administration of the territories failed at the Schloss Friedenstein in Gotha, the inheritance had to be distributed on 24 February 1680 among the seven brothers. The second eldest son of Ernst I “the Pious” of Saxe-Gotha, Albrecht, received the Principality of Saxe-Coburg. Like Saxe-Gotha under Duke Frederick and Saxe-Meiningen under Duke Bernhard I, the third oldest son, the Principality received full sovereignty in the Imperial Confederation. However, the Districts of Coburg, Neustadt bei Coburg, Sonneberg, Mönchröden, Sonnefeld and Neuhaus am Rennweg were considerably smaller than they were before, because Römhild and Hildburghausen were separated to supply the younger brother, the sixth oldest son, who became Ernest II, the first Duke of Saxe-Hildburghausen.

Duke Albert

Under Duke Albert, the expansion of his baroque residence in Coburg began. He based his life on the customs of his royal and princely contemporaries and tried to imitate their households on a smaller scale in Coburg. His court library consisted of 4,757 volumes. His plans to raise the Gymnasium Casimirianum to the rank of university failed because of the tight finances. The reconstruction of the Schloss Ehrenburg, burned in 1690, in the Baroque style eventually led to the ruin of the finances of the Principality, which could not be prevented by the minting of inferior coins. The Baroque Prince, Duke Albert, died in 1699 without any surviving descendants. This was followed by the usual inheritance disputes. Saxe-Hildburghausen got the District of Sonnefeld in 1707. Between Bernhard I of Saxe-Meiningen and his youngest brother John Ernest IV of Saxe-Saalfeld, strife lasted for thirty-five years, ending only in 1735 with several interventions from the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VI, in Vienna. Saxe-Meiningen received the District of Neuhaus am Rennweg and the jurisdiction of Sonneberg while Saxe-Saalfeld was united with the remaining territories of Saxe-Coburg to become Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. In 1753, it grew with the one-third of the Duchy of Saxe-Römhild, which had expired with the death of its only Duke, the childless Henry, Duke of Saxe-Römhild.

Duke Francis Josias

Duke Johann Ernest of Saxe-Saalfeld died in 1729. Afterwards, his sons Christian Ernest II and Francis Josias ruled the country together but in different residences. Christian Ernest remained in Saalfeld while Francis Josias chose Coburg as his residence and his decision would stand until the end of the monarchy in 1918. In 1745, Francis Josias inherited parts of Saxe-Coburg from his brother. In 1747, he was able to anchor his birthright (primogeniture) in the Line of Succession Laws and confer it on his rapidly growing family for the long-term survival of the House of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. In 1806, with the fall of the Holy Roman Empire, the Duchy became fully and truly independent.[2] In 1826, with the extensive rearrangement of the Ernestine duchies, Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld changed its name to Saxe-Coburg and Gotha with the personal union of two different duchies, Coburg and Gotha.

Sovereigns of Saxe-Coburg

Saxe-Coburg 1572–1638

- 1572–1586 Augustus, Elector of Saxony, Regent on behalf of John Casimir and John Ernest, the sons of Elector John Frederick II “the Middle”

- 1586–1596 Duke John Casimir, jointly with his brother John Ernest

- 1596–1633 Johann Casimir (1564–1633), alone

- 1633–1638 John Ernest, Duke of Saxe-Eisenach, brother of the previous Duke

- 1639–1669 Frederick William II, Duke of Saxe-Altenburg

- 1669–1672 Frederick William III, Duke of Saxe-Altenburg, son of the previous Duke, with John George II, Elector of Saxony and Maurice, Duke of Saxe-Zeitz as his Regents

- 1672–1674 Ernest I “the Pious”, Duke of Saxe-Gotha

- 1674–1680 Frederick I, Duke of Saxe-Gotha, 1st son of the previous Duke

Saxe-Coburg 1681–1735

- 1681–1699 Albert V, 2nd son of Ernest I “the Pious”

- 1699–1729 Johann Ernest IV, also Duke of Saxe-Saalfeld, 7th and youngest son of Ernest I “the Pious”, Duke of Saxe-Gotha

- 1729–1735 Christian Ernest II, also Duke of Saxe-Saalfeld, son of the previous Duke, jointly with his brother, Franz Josias

Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld 1735–1826

- 1735–1745 Christian Ernst, jointly with his brother, Francis Josias

- 1745–1764 Francis Josias, brother of the previous Duke

- 1764–1800 Ernest Frederick, son of the previous Duke

- 1800–1806 Francis Frederick Anton, son of the previous Duke

- 1806–1826 Ernest III, son of the previous Duke

Saxe-Coburg and Gotha 1826–1918

- 1826–1844 Ernest I

- 1844–1893 Ernest II, son of the previous Duke

- 1893–1900 Alfred, nephew of the previous Duke and son of Queen Victoria

- 1900–1905 Prince Ernest von Hohenlohe-Langenburg, Regent

- 1905–1918 Charles Edward, nephew of Duke Alfred, abdicated in 1918

See also

References

- (in German) Harald Bachmann, “Schloß Ehrenburg in Coburg”, in: Roswitha Jacobsen, ed., Die Residenz-Schlösser der Ernestiner [The Residential Palaces of the Ernestines] (Bucha bei Jena: Quartus-Verlag, 2009), p. 44.

- (in German) Harald Bachmann: “… all diese kleinen Fürsten werde ich davonjagen!” [ . . . all these little princes I will throw them out!], in: Stefan Nöth, ed., Coburg 1056 – 2006, Ein Streifzug durch 950 Jahre Geschichte von Stadt und Land [Coburg 1056 – 2006, a Ramble through 950 Years of History of the City and Land] (Stegaurach: Wikomm-Verlag, 2006), ISBN 3-86652-082-4, p. 181

Biography

- (in German) Carl-Christian Dressel, Die Entwicklung von Verfassung und Verwaltung in Sachsen-Coburg 1800 - 1826 im Vergleich [The Development and Comparison of the Constitution and Administration of Saxe-Coburg 1880 – 1826] (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2007), ISBN 978-3-428-12003-1.

- (in German) Thomas Nicklas, Das Haus Sachsen-Coburg – Europas späte Dynastie [The House of Saxe-Coburg — Europe's Last Dynasty] (Stuttgart: Verlag W[ilhelm]. Kohlhammer Verlag, 2003), ISBN 3-17-017243-3.

- (in German) Johann Hübner, Drey hundert drey und dreyßig Genealogische Tabellen: nebst denen darzu gehörigen genealogischen Fragen zur Erläuterung der politischen Historie, mit sonderbahrem Fleiße zusammen getragen, und vom Anfange der Welt biß auff diesen Tag continuiret; Nebst darzu dienlichen Registern [Three Hundred and Thirty Three Genealogical Tables: Together with those Related Questions of Genealogy to Explain the Political History, Compiled with Great Diligence, and Continuing from the Beginning of the World to This Day; Added Herein with Relevant Records] (Leipzig: Johann Friedrich Gleditsch, 1708) Table No. 164