Sayings of Jesus on the cross

The Sayings of Jesus on the cross (sometimes called the Seven Last Words from the Cross) are seven expressions biblically attributed to Jesus during his crucifixion. Traditionally, the brief sayings have been called "words". They are gathered from the four Canonical Gospels.[1][2] Three of the sayings appear only in the Gospel of Luke and two only in the Gospel of John. One other saying appears both in the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Mark, and another is only directly quoted in John but alluded to in Matthew and Mark.[3] In Matthew and Mark, Jesus cries out to God. In Luke, he forgives his killers, reassures the penitent thief, and commends his spirit to the Father. In John, he speaks to his mother, says he thirsts, and declares the end of his earthly life.

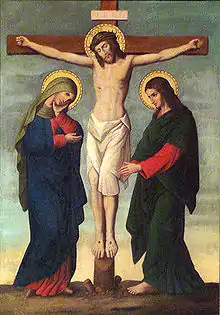

_-_James_Tissot.jpg.webp)

A person's final articulated words said prior to death or as death approaches generally are taken to have particular significance. These seven sayings, being "last words", may provide a way to understand what was ultimately important to this man who was dying on the cross.[4] The sparsity of sayings recorded in the biblical accounts suggests that Jesus remained relatively silent for the hours he hung there.[5]

Since the 16th century they have been widely used in sermons on Good Friday, and entire books have been written on theological analysis of them.[3][6][7][8] The Seven Last Words from the Cross are an integral part of the liturgy in the Anglican, Catholic, Protestant, and other Christian traditions.[9][10]

The seven-sayings tradition is an example of the Christian approach to the construction of a Gospel harmony in which material from different Gospels is combined, producing an account that goes beyond each Gospel.[3][11] Several composers have set the sayings to music.

Seven sayings

The seven sayings form part of a Christian meditation that is often used during Lent, Holy Week and Good Friday. The traditional order of the sayings is:[12]

- Luke 23:34: Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.

- Luke 23:43: Verily, I say unto you today, thou shalt be with me in paradise.

- John 19:26–27: Woman, behold thy son. (Says to disciple) Behold thy mother.

- Matthew 27:46 and Mark 15:34: My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?

- John 19:28: I thirst.

- John 19:30: It is finished.

- Luke 23:46: Father, into thy hands I commit my spirit.

Traditionally, these seven sayings are called words of 1. Forgiveness, 2. Salvation, 3. Relationship, 4. Abandonment, 5. Distress, 6. Triumph and 7. Reunion.[13]

As noted in the above list, not all seven sayings can be found in any one account of Jesus' crucifixion. The ordering is a harmonisation of the texts from each of the four canonical gospels. In the gospels of Matthew and Mark, Jesus is quoted in Aramaic, shouting the fourth phrase.. In Luke's Gospel, the first, second, and seventh sayings occur. The third, fifth and sixth sayings can only be found in John's Gospel. In other words:

- In Matthew and Mark :

- "My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?"

- In Luke:

- "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do"

- "Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in paradise (in response to one of the two thieves crucified next to him)

- "Father, into your hands I commit my spirit" (last words)

- In John:

- "Woman, behold your son: behold your mother" (directed at Mary, the mother of Jesus, either as a self-reference, or as a reference to the beloved disciple and an instruction to the disciple himself)

- "I thirst" (just before a wetted sponge, mentioned by all the Canonical Gospels, is offered)

- "It is finished" (last words)

1. Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do

- Then said Jesus, Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do.

This first saying of Jesus on the cross is traditionally called "The Word of Forgiveness".[13] It is theologically interpreted as Jesus' prayer for forgiveness for the Roman soldiers who were crucifying him and all others who were involved in his crucifixion.[14][15][16][17]

Some early manuscripts do not include this sentence in Luke 23:34.[18]

2. Today you will be with me in paradise

- "And he said to him, 'Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in paradise'."

This saying is traditionally called "The Word of Salvation".[13] According to Luke's Gospel, Jesus was crucified between two thieves (traditionally named Dismas and Gestas), one of whom supports Jesus' innocence and asks him to remember him when he comes into his kingdom. Jesus replies, "Truly, I say to you..." (ἀμήν λέγω σοί, amēn legō soi), followed with the only appearance of the word "Paradise" in the Gospels (παραδείσω, paradeisō, from the Persian pairidaeza "paradise garden").

A seemingly simple change in punctuation in this saying has been the subject of doctrinal differences among Christian groups, given the lack of punctuation in the original Greek texts.[19] Catholics and most Protestant Christians usually use a version which reads "today you will be with me in Paradise".[19] This reading assumes a direct voyage to Heaven and has no implications of purgatory.[19] On the other hand, some Protestants who believe in soul sleep have used a reading which emphasizes "I say to you today", leaving open the possibility that the statement was made today, but arrival in Heaven may be later.[19]

3. Woman, behold, thy son! Behold, thy mother!

- When Jesus, therefore, saw his mother, and the disciple standing by, whom he loved, he said to his mother, "Woman, behold, thy son!" After that, he said to the disciple, "Son, behold, thy mother!" And from that hour, that disciple took her unto his own home.

This statement is traditionally called "The Word of Relationship" and in it Jesus entrusts Mary, his mother, into the care of "the disciple whom Jesus loved".[13]

Methodist minister Adam Hamilton's 2009 interpretation: "Jesus looked down from the cross to see his mother standing nearby. As far as we know, only one of the twelve apostles was there at the foot of the cross: "the disciple whom Jesus loved," usually identified as John. Naked and in horrible pain, he thought not of himself but was concerned for the well-being of his mother after his death. This shows Jesus' humanity and the depth of love he had for his mother and the disciple into whose care he entrusted her."[4]

4. My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?

- And about the ninth hour, Jesus cried out with a loud voice, "Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?" that is, "My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?"

- And at the ninth hour, Jesus cried out with a loud voice, "Eloi Eloi lama sabachthani?" which means, "My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?"

This is the only saying which appears in more than one Gospel,[13] and is a quote from Psalm 22:1 (or probably Psalm 42:9). This saying is taken by some as an abandonment of the Son by the Father. Another interpretation holds that at the moment when Jesus took upon himself the sins of humanity, the Father had to turn away from the Son because the Father is "of purer eyes than to see evil and cannot look at wrong" (Habakkuk 1:13). Other theologians understand the cry as that of one who was truly human and who felt forsaken. Put to death by his foes, very largely deserted by his friends, he may have felt also deserted by God.[20]

Others point to this as the first words of Psalm 22 and suggest that Jesus recited these words, perhaps even the whole psalm, "that he might show himself to be the very Being to whom the words refer; so that the Jewish scribes and people might examine and see the cause why he would not descend from the cross; namely, because this very psalm showed that it was appointed that he should suffer these things."[21]

Theologian Frank Stagg points to what he calls "a mystery of Jesus' incarnation: "...he who died at Golgotha (Calvary) is one with the Father, that God was in Christ, and that at the same time he cried out to the Father".[22]

In Aramaic, the phrase was/is rendered, "אלי אלי למה שבקתני".

While "the nails in the wrists are putting pressure on the large median nerve, and the severely damaged nerve causes excruciating pain", the Lamb of God experiences the abandonment of the soul by God, a deeply excruciating pain that "is the essence of eternal condemnation in Hell".[23]

5. I thirst

- "He said, 'I thirst'."

This statement is traditionally called "The Word of Distress" and is compared and contrasted with the encounter of Jesus with the Samaritan Woman at the Well in John 4:4–26.[13]

As in the other accounts, the Gospel of John says Jesus was offered a drink of sour wine, adding that this person placed a sponge dipped in wine on a hyssop branch and held it to Jesus' lips. Hyssop branches had figured significantly in the Old Testament and they are referred to in the New Testament Letter to the Hebrews.[24]

This statement of Jesus is interpreted by John as fulfilment of the prophecy given in Psalm 69:21, "... and for my thirst they gave me vinegar to drink,[25] hence the quotation from John's Gospel includes the comment "to fulfill the scriptures". The Jerusalem Bible cross-references Psalm 22:15: my palate is drier than a potsherd, and my tongue is stuck to my jaw.[26]

6. It is finished

- "Jesus said, 'It is finished'" (τετέλεσται or tetelestai in Greek).[27]

This statement is traditionally called "The Word of Triumph" and is theologically interpreted as the announcement of the end of the earthly life of Jesus, in anticipation for the Resurrection.[13]

Adam Hamilton writes: "These last words are seen as a cry of victory, not of dereliction. Jesus had now completed what he came to do. A plan was fulfilled; a salvation was made possible; a love shown. He had taken our place. He had demonstrated both humanity's brokenness and God's love. He had offered himself fully to God as a sacrifice on behalf of humanity. As he died, it was finished. With these words, the noblest person who ever walked the face of this planet, God in the flesh, breathed his last."[4]:112

The verse has also been translated as "It is consummated."[28] On business documents or receipts it has been used to denote "The debt is paid in full".[29]

The utterance after consuming the beverage and immediately before death is mentioned, but not explicitly quoted, in Mark 15:37 and Matthew 27:50 (both of which state that he "cried out with a loud voice, and gave up the spirit").

7. Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit

- "And when Jesus had cried out with a loud voice, he said, Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit":

From Psalm 31:5, this saying, which is an announcement and not a request, is traditionally called "The Word of Reunion" and is theologically interpreted as the proclamation of Jesus joining God the Father in Heaven.[13]

Hamilton has written that "When darkness seem to prevail in life, it takes faith even to talk to God, even if it is to complain to him. These last words of Jesus from the cross show his absolute trust in God: "Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit: ..." This has been termed a model of prayer for everyone when afraid, sick, or facing one's own death. It says in effect:

I commit myself to you, O God. In my living and in my dying, in the good times and in the bad, whatever I am and have, I place in your hands, O God, for your safekeeping.[4]:112

Theological interpretations

The last words of Jesus have been the subject of a wide range of Christian teachings and sermons, and a number of authors have written books specifically devoted to the last sayings of Christ.[30][31][32]

Priest and author Timothy Radcliffe states that in the Bible, seven is the number of perfection, and he views the seven last words as God's completion of the circle of creation and performs analysis of the structure of the seven last words to obtain further insight.[33]

Other interpretations and translations

The saying "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me" is generally given in transliterated Aramaic with a translation (originally in Greek) after it. This phrase is the opening line of Psalm 22, a psalm about persecution, the mercy and salvation of God. It was common for people at this time to reference songs by quoting their first lines. In the verses immediately following this saying, in both Gospels, the onlookers who hear Jesus' cry understand him to be calling for help from Elijah (Eliyyâ). The slight differences between the two gospel accounts are most probably due to dialect. Matthew's version seems to have been more influenced by Hebrew, whereas Mark's is perhaps more colloquial.

The phrase could be either:

- אלי אלי למה עזבתני [ēlî ēlî lamâ azavtanî]; or

- אלי אלי למא שבקתני [ēlî ēlî lamâ šabaqtanî]; or

- אלהי אלהי למא שבקתני [ēlâhî ēlâhî lamâ šabaqtanî]

In the first example, above, the word "עזבתני" translates not as "forsaken", but as "left", as if calling out that God has left him to die on the cross or has departed and left him alone in his time of greatest pain and suffering.

The Aramaic word šabaqtanî is based on the verb šabaq, 'to allow, to permit, to forgive, and to forsake', with the perfect tense ending -t (2nd person singular: 'you'), and the object suffix -anî (1st person singular: 'me').[34]

A. T. Robertson noted that the "so-called Gospel of Peter 1.5 preserves this saying in a Docetic (Cerinthian) form: 'My power, my power, thou hast forsaken me!'"[35]

Science fiction

Michael Moorcock's Science Fiction novel Behold the Man assumes that Jesus was a time-traveller from the 20th century and that in his agony on the cross he cried out in English "It's a lie...It's a lie...It's a lie", which Aramaic-speaking spectators misinterpreted as the words enshrined in the New Testament text.

In C. S. Lewis' novel Perelandra, the protagonist Ransom confronts a demonically-possessed opponent. At the height of their confrontation, the demon repeats Jesus' words "Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani" and Ransom realizes with a shock that his opponent is not quoting from the New Testament but directly recalling having been present at the Crucifixion and gloatingly enjoyed seeing Jesus' agony. This infuriates Ransom and confirms him in overcoming his scruples and fighting all-out to obliterate the demon.

Historicity

James Dunn considers the seven sayings weakly rooted in tradition and sees them as a part of the elaborations in the diverse retellings of Jesus' final hours.[36] Dunn, however, argues in favour of the authenticity of the Mark/Matthew saying in that by presenting Jesus as seeing himself 'forsaken' it would have been an embarrassment to the early Church, and hence would not have been invented.[36] Geza Vermes, states that the first saying from (Matthew and Mark) is a quotation from Psalm 22, and is therefore occasionally seen as a theological and literary device employed by the writers.[37] According to Vermes, attempts to interpret the expression as a hopeful reference to scripture provide indirect evidence of its authenticity.[38] Leslie Houlden, on the other hand, states that Luke may have deliberately excluded the Matthew/Mark saying from his Gospel because it did not fit in the model of Jesus he was presenting.[3][7]

See also

Notes

- Geoffrey W. Bromiley, International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Eerdmans Press 1995, ISBN 0-8028-3784-0 p. 426

- Joseph F. Kelly, An Introduction to the New Testament for Catholics Liturgical Press, 2006 ISBN 978-0-8146-5216-9 p. 153

- Jesus: the complete guide by Leslie Houlden 2006 ISBN 0-8264-8011-X p. 627

- Hamilton, Adam. 24 Hours That Changed the World. Abingdon Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-687-46555-2

- Wilson, Ralph F. "The Seven Last Words of Christ from the Cross".<http://www.jesuswalk.com/7-last-words/>

- Jesus of Nazareth by W. Mccrocklin 2006 ISBN 1-59781-863-1 p. 134

- Jesus in history, thought, and culture: an encyclopedia, Volume 1 by James Leslie Houlden 2003 ISBN 1-57607-856-6 p. 645

- The Seven Last Words From The Cross by Fleming Rutledge 2004 ISBN 0-8028-2786-1 pp. 8–10

- Richard Young (Feb 25, 2005). Echoes from Calvary: meditations on Franz Joseph Haydn's The seven last words of Christ, Volume 1. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0742543843. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

Interestingly, the Methodist Book of Worship adopted by the General Conference of 1964 presented two services for Good Friday: a Three Hours' Service for the afternoon and a Good Friday evening service that includes the "Adoration at the Cross" (the Gospel, Deprecations, and Adoration of the Cross) but omits a communion service, which would be the Methodist equivalent of the Mass of the Presanctified.

- The Encyclopædia Americana: a library of universal knowledge, Volume 13. Encyclopedia Americana. 1919. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

The 'Three Hours' Devotion, borrowed from Roman usage, with meditation on the 'seven last words' from the Cross, and held from 12 till 3, when our Lord hung on the Cross, is a service of Good Friday that meets with increasing acceptance among the Anglicans.

- Ehrman, Bart D.. Jesus, Interrupted, HarperCollins, 2009. ISBN 0-06-117393-2

- Jan Majernik, The Synoptics, Emmaus Road Press: 2005 ISBN 1-931018-31-6, p. 190

- The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1988 ISBN 0-8028-3785-9 p. 426

- Vernon K. Robbins in Literary studies in Luke-Acts by Richard P. Thompson (editor) 1998 ISBN 0-86554-563-4 pp. 200–01

- Mercer dictionary of the Bible by Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard 1998 ISBN 0-86554-373-9 p. 648

- Reading Luke-Acts: dynamics of Biblical narrative by William S. Kurz 1993 ISBN 0-664-25441-1 p. 201

- Luke's presentation of Jesus: a Christology by de:Robert F. O'Toole 2004 ISBN 88-7653-625-6 p. 215

- Steven L. Cox, Kendell H. Easley, 2007 Harmony of the Gospels ISBN 0-8054-9444-8 p. 234

- The Blackwell Companion to Catholicism by James Buckley, Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt and Trent Pomplun, 2010 ISBN 1-4443-3732-7 p. 48

- Conner, W.T. The Cross in the New Testament. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1954. ASIN B0007EIIPI p. 34

- "Pulpit Commentary". See Mark 15:34, http://biblehub.com/commentaries/pulpit/mark/15.htm

- Stagg, Frank. New Testament Theology. Broadman Press, 1962. ISBN 0-8054-1613-7

- "Seven words from the cross (reflection)". Ukrainian Orthodox Greek-Catholic Church. Feb 28, 2011. Archived from the original on Aug 13, 2018.

- Hyssop. cf. Exodus 12:22: used to sprinkle the blood of the Passover lamb above the doors of the Israelite's dwellings when the firstborn of the Egyptians were killed; Leviticus 14: hyssop wrapped in yarn was used to sprinkle blood and water upon the lepers; Leviticus 14: hyssop wrapped in yarn also used on the ceremonially unclean so they might be made clean again; Psalm 51:7: David, in his prayer of confession, cried out to God, "Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean."; and Hebrews 9:19–20: after Moses gave the people the Ten Commandments, "he took the blood of calves and goats, with water and scarlet wool and hyssop, and sprinkled both the scroll itself and all the people, saying, 'This is the blood of the covenant that God has ordained for you.'" Hamilton, Adam (2009). 24 Hours That Changed the World. Nashville: Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0-687-46555-2.

- Nicoll, W. R., Expositor's Greek Testement on John 19, accessed 15 May 2020

- Jerusalem Bible (1966): Psalm 22:15

- https://bible.org/question/what-does-greek-word-tetelestai-mean

- "John 19:30". Douay-Rheims Bible.

Jesus therefore, when he had taken the vinegar, said: It is consummated. And bowing his head, he gave up the ghost.

- Milligan, George. (1997). The vocabulary of the Greek Testament. Hendrickson. ISBN 1-56563-271-0. OCLC 909241038.

- David Anderson-Berry, The Seven Sayings of Christ on the Cross, Glasgow: Pickering & Inglis Publishers, 1871

- Arthur Pink, The Seven Sayings of the Saviour on the Cross, Baker Books 2005, ISBN 0-8010-6573-9

- Simon Peter Long, The wounded Word: A brief meditation on the seven sayings of Christ on the cross, Baker Books 1966

- Timothy Radcliffe, 2005 Seven Last Words, ISBN 0-86012-397-9 p. 11

- Dictionary of biblical tradition in English literature by David L. Jeffrey 1993 ISBN 0-8028-3634-8 p. 233

- Robertson's Word Pictures of the New Testament (Broadman-Holman, 1973), vol. 1. ISBN 0-8054-1307-3.

- James G. D. Dunn, Jesus Remembered, Eerdmans, 2003, pp. 779–81.

- Geza Vermes, The Passion, Penguin 2005, p. 75.

- Vermes, Géza. The authentic gospel of Jesus. London, Penguin Books. 2004.

References

External links

- The Seven Last Words of Christ, Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts, Patheos

- The Seven Last Words of Christ: free scores in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)