Schwarzschild geodesics

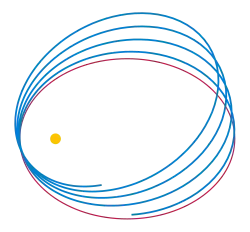

In general relativity, Schwarzschild geodesics describe the motion of test particles in the gravitational field of a central fixed mass , that is, motion in the Schwarzschild metric. Schwarzschild geodesics have been pivotal in the validation of Einstein's theory of general relativity. For example, they provide accurate predictions of the anomalous precession of the planets in the Solar System and of the deflection of light by gravity.

| Part of a series of articles about |

| General relativity |

|---|

|

Schwarzschild geodesics pertain only to the motion of particles of masses so small they contribute little to the gravitational field. However, they are highly accurate in many astrophysical scenarios provided that is many-fold smaller than the central mass , e.g., for planets orbiting their sun. Schwarzschild geodesics are also a good approximation to the relative motion of two bodies of arbitrary mass, provided that the Schwarzschild mass is set equal to the sum of the two individual masses and . This is important in predicting the motion of binary stars in general relativity.

Historical context

The Schwarzschild metric is named in honour of its discoverer Karl Schwarzschild, who found the solution in 1915, only about a month after the publication of Einstein's theory of general relativity. It was the first exact solution of the Einstein field equations other than the trivial flat space solution.

In 1935, Yusuke Hagihara published a paper showing that the trajectory of a test particle in the Schwarzschild metric can be expressed in terms of elliptic functions.[1]

Schwarzschild metric

An exact solution to the Einstein field equations is the Schwarzschild metric, which corresponds to the external gravitational field of an uncharged, non-rotating, spherically symmetric body of mass . The Schwarzschild solution can be written as[2]

where

- is the proper time (time measured by a clock moving with the particle) in seconds,

- is the speed of light in meters per second,

- is the time coordinate (time measured by a stationary clock at infinity) in seconds,

- is the radial coordinate (circumference of a circle centered at the star divided by ) in meters,

- is the colatitude (angle from North) in radians,

- is the longitude in radians, and

- is the Schwarzschild radius of the massive body (in meters), which is related to its mass by

- where is the gravitational constant. The classical Newtonian theory of gravity is recovered in the limit as the ratio goes to zero. In that limit, the metric returns to that defined by special relativity.

In practice, this ratio is almost always extremely small. For example, the Schwarzschild radius of the Earth is roughly 9 mm (3⁄8 inch); at the surface of the Earth, the corrections to Newtonian gravity are only one part in a billion. The Schwarzschild radius of the Sun is much larger, roughly 2953 meters, but at its surface, the ratio is roughly 4 parts in a million. A white dwarf star is much denser, but even here the ratio at its surface is roughly 250 parts in a million. The ratio only becomes large close to ultra-dense objects such as neutron stars (where the ratio is roughly 50%) and black holes.

Orbits of test particles

We may simplify the problem by using symmetry to eliminate one variable from consideration. Since the Schwarzschild metric is symmetrical about , any geodesic that begins moving in that plane will remain in that plane indefinitely (the plane is totally geodesic). Therefore, we orient the coordinate system so that the orbit of the particle lies in that plane, and fix the coordinate to be so that the metric (of this plane) simplifies to

Two constants of motion (values that do not change over proper time ) can be identified (cf. the derivation given below). One is the total energy :

and the other is the specific angular momentum:

where L is the total angular momentum of the two bodies, and is the reduced mass. When , the reduced mass is approximately equal to . Sometimes it is assumed that . In the case of the planet Mercury this simplification introduces an error more than twice as large as the relativistic effect. When discussing geodesics, can be considered fictitious, and what matters are the constants and . In order to cover all possible geodesics, we need to consider cases in which is infinite (giving trajectories of photons) or imaginary (for tachyonic geodesics). For the photonic case, we also need to specify a number corresponding to the ratio of the two constants, namely , which may be zero or a non-zero real number.

Substituting these constants into the definition of the Schwarzschild metric

yields an equation of motion for the radius as a function of the proper time :

The formal solution to this is

Note that the square root will be imaginary for tachyonic geodesics.

Using the relation higher up between and , we can also write

Since asymptotically the integrand is inversely proportional to , this shows that in the frame of reference if approaches it does so exponentially without ever reaching it. However, as a function of , does reach .

The above solutions are valid while the integrand is finite, but a total solution may involve two or an infinity of pieces, each described by the integral but with alternating signs for the square root.

When and , we can solve for and explicitly:

and for photonic geodesics () with zero angular momentum

(Although the proper time is trivial in the photonic case, one can define an affine parameter , and then the solution to the geodesic equation is .)

Another solvable case is that in which and and are constant. In the volume where this gives for the proper time

This is close to solutions with small and positive. Outside of the solution is tachyonic and the "proper time" is space-like:

This is close to other tachyonic solutions with small and negative. The constant tachyonic geodesic outside is not continued by a constant geodesic inside , but rather continues into a "parallel exterior region" (see Kruskal–Szekeres coordinates). Other tachyonic solutions can enter a black hole and re-exit into the parallel exterior region. The constant t solution inside the event horizon () is continued by a constant t solution in a white hole.

When the angular momentum is not zero we can replace the dependence on proper time by a dependence on the angle using the definition of

which yields the equation for the orbit

where, for brevity, two length-scales, and , have been defined by

Note that in the tachyonic case, will be imaginary and real or infinite.

The same equation can also be derived using a Lagrangian approach[3] or the Hamilton–Jacobi equation[4] (see below). The solution of the orbit equation is

This can be expressed in terms of the Weierstrass elliptic function .[5]

Local and delayed velocities

Unlike in classical mechanics, in Schwarzschild coordinates and are not the radial and transverse components of the local velocity (relative to a stationary observer), instead they give the components for the celerity which are related to by

for the radial and

for the transverse component of motion, with . The coordinate bookkeeper far away from the scene observes the shapiro-delayed velocity , which is given by the relation

- and .

The time dilation factor between the bookkeeper and the moving test-particle can also be put into the form

where the numerator is the gravitational, and the denominator is the kinematic component of the time dilation. For a particle falling in from infinity the left factor equals the right factor, since the in-falling velocity matches the escape velocity in this case.

The two constants angular momentum and total energy of a test-particle with mass are in terms of

and

where

and

For massive testparticles is the Lorentz factor and is the proper time, while for massless particles like photons is set to and takes the role of an affine parameter. If the particle is massless is replaced with and with , where is the Planck constant and the locally observed frequency.

Exact solution using elliptic functions

The fundamental equation of the orbit is easier to solve[note 1] if it is expressed in terms of the inverse radius

The right-hand side of this equation is a cubic polynomial, which has three roots, denoted here as u1, u2, and u3

The sum of the three roots equals the coefficient of the u2 term

A cubic polynomial with real coefficients can either have three real roots, or one real root and two complex conjugate roots. If all three roots are real numbers, the roots are labeled so that u1 < u2 < u3. If instead there is only one real root, then that is denoted as u3; the complex conjugate roots are labeled u1 and u2. Using Descartes' rule of signs, there can be at most one negative root; u1 is negative if and only if b < a. As discussed below, the roots are useful in determining the types of possible orbits.

Given this labeling of the roots, the solution of the fundamental orbital equation is

where sn represents the sinus amplitudinus function (one of the Jacobi elliptic functions) and δ is a constant of integration reflecting the initial position. The elliptic modulus k of this elliptic function is given by the formula

Newtonian limit

To recover the Newtonian solution for the planetary orbits, one takes the limit as the Schwarzschild radius rs goes to zero. In this case, the third root u3 becomes roughly , and much larger than u1 or u2. Therefore, the modulus k tends to zero; in that limit, sn becomes the trigonometric sine function

Consistent with Newton's solutions for planetary motions, this formula describes a focal conic of eccentricity e

If u1 is a positive real number, then the orbit is an ellipse where u1 and u2 represent the distances of furthest and closest approach, respectively. If u1 is zero or a negative real number, the orbit is a parabola or a hyperbola, respectively. In these latter two cases, u2 represents the distance of closest approach; since the orbit goes to infinity (u = 0), there is no distance of furthest approach.

Roots and overview of possible orbits

A root represents a point of the orbit where the derivative vanishes, i.e., where . At such a turning point, u reaches a maximum, a minimum, or an inflection point, depending on the value of the second derivative, which is given by the formula

If all three roots are distinct real numbers, the second derivative is positive, negative, and positive at u1,u2, and u3, respectively. It follows that a graph of u versus φ may either oscillate between u1 and u2, or it may move away from u3 towards infinity (which corresponds to r going to zero). If u1 is negative, only part of an "oscillation" will actually occur. This corresponds to the particle coming from infinity, getting near the central mass, and then moving away again toward infinity, like the hyperbolic trajectory in the classical solution.

If the particle has just the right amount of energy for its angular momentum, u2 and u3 will merge. There are three solutions in this case. The orbit may spiral in to , approaching that radius as (asymptotically) a decreasing exponential in φ, τ, or t. Or one can have a circular orbit at that radius. Or one can have an orbit that spirals down from that radius to the central point. The radius in question is called the inner radius and is between and 3 times rs. A circular orbit also results when u2 is equal to u1, and this is called the outer radius. These different types of orbits are discussed below.

If the particle comes at the central mass with sufficient energy and sufficiently low angular momentum then only u1 will be real. This corresponds to the particle falling into a black hole. The orbit spirals in with a finite change in φ.

Precession of orbits

The function sn and its square sn2 have periods of 4K and 2K, respectively, where K is defined by the equation[note 2]

Therefore, the change in φ over one oscillation of u (or, equivalently, one oscillation of r) equals[6]

In the classical limit, u3 approaches and is much larger than u1 or u2. Hence, k2 is approximately

For the same reasons, the denominator of Δφ is approximately

Since the modulus k is close to zero, the period K can be expanded in powers of k; to lowest order, this expansion yields

Substituting these approximations into the formula for Δφ yields a formula for angular advance per radial oscillation

For an elliptical orbit, u1 and u2 represent the inverses of the longest and shortest distances, respectively. These can be expressed in terms of the ellipse's semi-major axis A and its orbital eccentricity e,

giving

Substituting the definition of rs gives the final equation

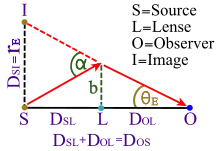

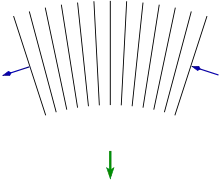

Bending of light by gravity

In the limit as the particle mass m goes to zero (or, equivalently if the light is heading directly toward the central mass, as the length-scale a goes to infinity), the equation for the orbit becomes

Expanding in powers of , the leading order term in this formula gives the approximate angular deflection δφ for a massless particle coming in from infinity and going back out to infinity:

Here, b is the impact parameter, somewhat greater than the distance of closest approach, r3:[7]

Although this formula is approximate, it is accurate for most measurements of gravitational lensing, due to the smallness of the ratio . For light grazing the surface of the sun, the approximate angular deflection is roughly 1.75 arcseconds, roughly one millionth part of a circle.

Relation to Newtonian physics

Effective radial potential energy

The equation of motion for the particle derived above

can be rewritten using the definition of the Schwarzschild radius rs as

which is equivalent to a particle moving in a one-dimensional effective potential

The first two terms are well-known classical energies, the first being the attractive Newtonian gravitational potential energy and the second corresponding to the repulsive "centrifugal" potential energy; however, the third term is an attractive energy unique to general relativity. As shown below and elsewhere, this inverse-cubic energy causes elliptical orbits to precess gradually by an angle δφ per revolution

where A is the semi-major axis and e is the eccentricity.

The third term is attractive and dominates at small r values, giving a critical inner radius rinner at which a particle is drawn inexorably inwards to r = 0; this inner radius is a function of the particle's angular momentum per unit mass or, equivalently, the a length-scale defined above.

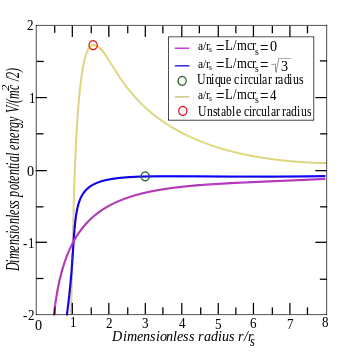

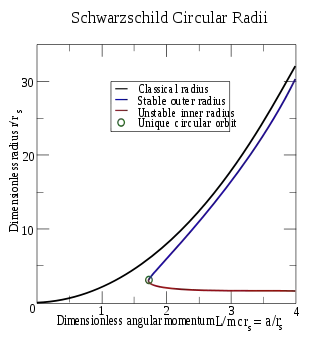

Circular orbits and their stability

The effective potential V can be re-written in terms of the length .

Circular orbits are possible when the effective force is zero

i.e., when the two attractive forces — Newtonian gravity (first term) and the attraction unique to general relativity (third term) — are exactly balanced by the repulsive centrifugal force (second term). There are two radii at which this balancing can occur, denoted here as rinner and router

which are obtained using the quadratic formula. The inner radius rinner is unstable, because the attractive third force strengthens much faster than the other two forces when r becomes small; if the particle slips slightly inwards from rinner (where all three forces are in balance), the third force dominates the other two and draws the particle inexorably inwards to r = 0. At the outer radius, however, the circular orbits are stable; the third term is less important and the system behaves more like the non-relativistic Kepler problem.

When a is much greater than rs (the classical case), these formulae become approximately

Substituting the definitions of a and rs into router yields the classical formula for a particle of mass m orbiting a body of mass M.

where ωφ is the orbital angular speed of the particle. This formula is obtained in non-relativistic mechanics by setting the centrifugal force equal to the Newtonian gravitational force:

Where is the reduced mass.

In our notation, the classical orbital angular speed equals

At the other extreme, when a2 approaches 3rs2 from above, the two radii converge to a single value

The quadratic solutions above ensure that router is always greater than 3rs, whereas rinner lies between 3⁄2 rs and 3rs. Circular orbits smaller than 3⁄2 rs are not possible. For massless particles, a goes to infinity, implying that there is a circular orbit for photons at rinner = 3⁄2 rs. The sphere of this radius is sometimes known as the photon sphere.

Precession of elliptical orbits

The orbital precession rate may be derived using this radial effective potential V. A small radial deviation from a circular orbit of radius router will oscillate stably with an angular frequency

which equals

Taking the square root of both sides and performing a Taylor series expansion yields

Multiplying by the period T of one revolution gives the precession of the orbit per revolution

where we have used ωφT = 2п and the definition of the length-scale a. Substituting the definition of the Schwarzschild radius rs gives

This may be simplified using the elliptical orbit's semiaxis A and eccentricity e related by the formula

to give the precession angle

Mathematical derivations of the orbital equation

Geodesic equation

According to Einstein's theory of general relativity, particles of negligible mass travel along geodesics in the space-time. In flat space-time, far from a source of gravity, these geodesics correspond to straight lines; however, they may deviate from straight lines when the space-time is curved. The equation for the geodesic lines is[9]

where Γ represents the Christoffel symbol and the variable parametrizes the particle's path through space-time, its so-called world line. The Christoffel symbol depends only on the metric tensor , or rather on how it changes with position. The variable is a constant multiple of the proper time for timelike orbits (which are traveled by massive particles), and is usually taken to be equal to it. For lightlike (or null) orbits (which are traveled by massless particles such as the photon), the proper time is zero and, strictly speaking, cannot be used as the variable . Nevertheless, lightlike orbits can be derived as the ultrarelativistic limit of timelike orbits, that is, the limit as the particle mass m goes to zero while holding its total energy fixed.

Therefore, to solve for the motion of a particle, the most straightforward way is to solve the geodesic equation, an approach adopted by Einstein[10] and others.[11] The Schwarzschild metric may be written as

where the two functions and its reciprocal are defined for brevity. From this metric, the Christoffel symbols may be calculated, and the results substituted into the geodesic equations

It may be verified that is a valid solution by substitution into the first of these four equations. By symmetry, the orbit must be planar, and we are free to arrange the coordinate frame so that the equatorial plane is the plane of the orbit. This solution simplifies the second and fourth equations.

To solve the second and third equations, it suffices to divide them by and , respectively.

which yields two constants of motion.

Lagrangian approach

Because test particles follow geodesics in a fixed metric, the orbits of those particles may be determined using the calculus of variations, also called the Lagrangian approach.[12] Geodesics in space-time are defined as curves for which small local variations in their coordinates (while holding their endpoints events fixed) make no significant change in their overall length s. This may be expressed mathematically using the calculus of variations

where τ is the proper time, s = cτ is the arc-length in space-time and T is defined as

in analogy with kinetic energy. If the derivative with respect to proper time is represented by a dot for brevity

T may be written as

Constant factors (such as c or the square root of two) don't affect the answer to the variational problem; therefore, taking the variation inside the integral yields Hamilton's principle

The solution of the variational problem is given by Lagrange's equations

When applied to t and φ, these equations reveal two constants of motion

which may be expressed in terms of two constant length-scales, and

As shown above, substitution of these equations into the definition of the Schwarzschild metric yields the equation for the orbit.

Hamiltonian approach

A Lagrangian solution can be recast into an equivalent Hamiltonian form.[13] In this case, the Hamiltonian is given by

Once again, the orbit may be restricted to by symmetry. Since and do not appear in the Hamiltonian, their conjugate momenta are constant; they may be expressed in terms of the speed of light and two constant length-scales and

The derivatives with respect to proper time are given by

Dividing the first equation by the second yields the orbital equation

The radial momentum pr can be expressed in terms of r using the constancy of the Hamiltonian ; this yields the fundamental orbital equation

Hamilton–Jacobi approach

The orbital equation can be derived from the Hamilton–Jacobi equation.[14] The advantage of this approach is that it equates the motion of the particle with the propagation of a wave, and leads neatly into the derivation of the deflection of light by gravity in general relativity, through Fermat's principle. The basic idea is that, due to gravitational slowing of time, parts of a wave-front closer to a gravitating mass move more slowly than those further away, thus bending the direction of the wave-front's propagation.

Using general covariance, the Hamilton–Jacobi equation for a single particle of unit mass can be expressed in arbitrary coordinates as

This is equivalent to the Hamiltonian formulation above, with the partial derivatives of the action taking the place of the generalized momenta. Using the Schwarzschild metric gμν, this equation becomes

where we again orient the spherical coordinate system with the plane of the orbit. The time t and azimuthal angle φ are cyclic coordinates, so that the solution for Hamilton's principal function S can be written

where pt and pφ are the constant generalized momenta. The Hamilton–Jacobi equation gives an integral solution for the radial part Sr(r)

Taking the derivative of Hamilton's principal function S with respect to the conserved momentum pφ yields

which equals

Taking an infinitesimal variation in φ and r yields the fundamental orbital equation

where the conserved length-scales a and b are defined by the conserved momenta by the equations

Hamilton's principle

The action integral for a particle affected only by gravity is

where is the proper time and is any smooth parameterization of the particle's world line. If one applies the calculus of variations to this, one again gets the equations for a geodesic. To simplify the calculations, one first takes the variation of the square of the integrand. For the metric and coordinates of this case and assuming that the particle is moving in the equatorial plane , that square is

Taking variation of this gives

Motion in longitude

Vary with respect to longitude only to get

Divide by to get the variation of the integrand itself

Thus

Integrating by parts gives

The variation of the longitude is assumed to be zero at the end points, so the first term disappears. The integral can be made nonzero by a perverse choice of unless the other factor inside is zero everywhere. So the equation of motion is

Motion in time

Vary with respect to time only to get

Divide by to get the variation of the integrand itself

Thus

Integrating by parts gives

So the equation of motion is

Conserved momenta

Integrate these equations of motion to determine the constants of integration getting

These two equations for the constants of motion (angular momentum) and (energy) can be combined to form one equation that is true even for photons and other massless particles for which the proper time along a geodesic is zero.

Radial motion

Substituting

and

into the metric equation (and using ) gives

from which one can derive

which is the equation of motion for . The dependence of on can be found by dividing this by

to get

which is true even for particles without mass. If length scales are defined by

and

then the dependence of on simplifies to

See also

Notes

- This substitution of u for r is also common in classical central-force problems, since it also renders those equations easier to solve. For further information, please see the article on the classical central-force problem.

- In the mathematical literature, K is known as the complete elliptic integral of the first kind; for further information, please see the article on elliptic integrals.

References

- Kozai, Yoshihide (1998). "Development of Celestial Mechanics in Japan". Planet. Space Sci. 46 (8): 1031–36. Bibcode:1998P&SS...46.1031K. doi:10.1016/s0032-0633(98)00033-6.

- Landau and Lifshitz, pp. 299–301.

- Whittaker 1937.

- Landau and Lifshitz (1975), pp. 306–309.

- Gibbons, G. W.; Vyska, M. (February 29, 2012). "The application of Weierstrass elliptic functions to Schwarzschild null geodesics". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 29 (6). arXiv:1110.6508. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/29/6/065016.

- Synge, pp. 294–295.

- arXiv.org: gr-qc/9907034v1.

- Sean Carroll: Lecture Notes on General Relativity, Chapter 7, Eq. 7.33

- Weinberg, p. 122.

- Einstein, pp. 95–96.

- Weinberg, pp. 185–188; Wald, pp. 138–139.

- Synge, pp. 290–292; Adler, Bazin, and Schiffer, pp. 179–182; Whittaker, pp. 390–393; Pauli, p. 167.

- Lanczos, pp. 331–338.

- Landau and Lifshitz, pp. 306–307; Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler, pp. 636–679.

Bibliography

- Schwarzschild, K. (1916). Über das Gravitationsfeld eines Massenpunktes nach der Einstein'schen Theorie. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1, 189–196.

- Schwarzschild, K. (1916). Über das Gravitationsfeld einer Kugel aus inkompressibler Flüssigkeit. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1, 424-?.

- Flamm, L (1916). "Beiträge zur Einstein'schen Gravitationstheorie". Physikalische Zeitschrift. 17: 448–?.

- Adler, R; Bazin M; Schiffer M (1965). Introduction to General Relativity. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 177–193. ISBN 978-0-07-000420-7.

- Einstein, A (1956). The Meaning of Relativity (5th ed.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 92–97. ISBN 978-0-691-02352-6.

- Hagihara, Y (1931). "Theory of the relativistic trajectories in a gravitational field of Schwarzschild". Japanese Journal of Astronomy and Geophysics. 8: 67–176. ISSN 0368-346X.

- Lanczos, C (1986). The Variational Principles of Mechanics (4th ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 330–338. ISBN 978-0-486-65067-8.

- Landau, LD; Lifshitz, EM (1975). The Classical Theory of Fields. Course of Theoretical Physics. Vol. 2 (revised 4th English ed.). New York: Pergamon Press. pp. 299–309. ISBN 978-0-08-018176-9.

- Misner, CW; Thorne, K & Wheeler, JA (1973). Gravitation. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. pp. Chapter 25 (pp. 636–687), §33.5 (pp. 897–901), and §40.5 (pp. 1110–1116). ISBN 978-0-7167-0344-0. (See Gravitation (book).)

- Pais, A. (1982). Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein. Oxford University Press. pp. 253–256. ISBN 0-19-520438-7.

- Pauli, W (1958). Theory of Relativity. Translated by G. Field. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 40–41, 166–169. ISBN 978-0-486-64152-2.

- Rindler, W (1977). Essential Relativity: Special, General, and Cosmological (revised 2nd ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. pp. 143–149. ISBN 978-0-387-10090-6.

- Roseveare, N. T (1982). Mercury's perihelion, from Leverrier to Einstein. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 0-19-858174-2.

- Synge, JL (1960). Relativity: The General Theory. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing. pp. 289–298. ISBN 978-0-7204-0066-3.

- Wald, RM (1984). General Relativity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 136–146. ISBN 978-0-226-87032-8.

- Walter, S. (2007). "Breaking in the 4-vectors: the four-dimensional movement in gravitation, 1905–1910". In Renn, J. (ed.). The Genesis of General Relativity. 3. Berlin: Springer. pp. 193–252.

- Weinberg, S (1972). Gravitation and Cosmology. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 185–201. ISBN 978-0-471-92567-5.

- Whittaker, ET (1937). A Treatise on the Analytical Dynamics of Particles and Rigid Bodies, with an Introduction to the Problem of Three Bodies (4th ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 389–393. ISBN 978-1-114-28944-4.

External links

- Excerpt from Reflections on Relativity by Kevin Brown.