Albert Einstein

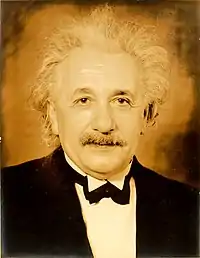

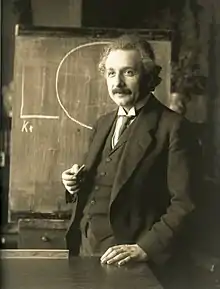

Albert Einstein (/ˈaɪnstaɪn/ EYEN-styne;[4] German: [ˈalbɛʁt ˈʔaɪnʃtaɪn] (![]() listen); 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist[5] who developed the theory of relativity, one of the two pillars of modern physics (alongside quantum mechanics).[3][6] His work is also known for its influence on the philosophy of science.[7][8] He is best known to the general public for his mass–energy equivalence formula E = mc2, which has been dubbed "the world's most famous equation".[9] He received the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect",[10] a pivotal step in the development of quantum theory.

listen); 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist[5] who developed the theory of relativity, one of the two pillars of modern physics (alongside quantum mechanics).[3][6] His work is also known for its influence on the philosophy of science.[7][8] He is best known to the general public for his mass–energy equivalence formula E = mc2, which has been dubbed "the world's most famous equation".[9] He received the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect",[10] a pivotal step in the development of quantum theory.

The son of a salesman who later operated an electrochemical factory, Einstein was born in the German Empire, but moved to Switzerland in 1895, forsaking his German citizenship the following year. Specializing in physics and mathematics, he received his academic teaching diploma from the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School in Zürich in 1900. The following year, he acquired Swiss citizenship, which he kept for his entire life. After initially struggling to find work, from 1902 to 1909 he was employed as a patent examiner at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern.

Near the beginning of his career, Einstein thought that the laws of classical mechanics could no longer be reconciled with those of the electromagnetic field. This led him to develop his special theory of relativity during his time as a patent clerk. In 1905, called his annus mirabilis ('miracle year'), he published four groundbreaking papers which attracted the attention of the academic world; the first paper outlined the theory of the photoelectric effect, the second explained Brownian motion, the third introduced special relativity, and the fourth mass–energy equivalence. That year, at the age of 26, he was awarded a PhD by the University of Zurich.

Although initially treated with skepticism from many in the scientific community, Einstein's works gradually came to be recognised as significant advancements. He was invited to teach theoretical physics at the University of Bern in 1908 and the following year moved to the University of Zurich, then in 1911 to Charles University in Prague before returning to ETH (the newly renamed Federal Polytechnic School) in Zürich in 1912. In 1914, he was elected to the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin, where he remained for 19 years. Soon after publishing his work on special relativity, Einstein began working to extend the theory to gravitational fields; he then published a paper on general relativity in 1916, introducing his theory of gravitation. He continued to deal with problems of statistical mechanics and quantum theory, which led to his explanations of particle theory and the motion of molecules. He also investigated the thermal properties of light and the quantum theory of radiation, the basis of the laser, which laid the foundation of the photon theory of light. In 1917, he applied the general theory of relativity to model the structure of the universe.[11][12]

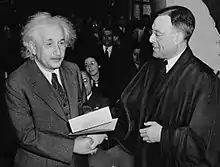

In 1933, while Einstein was visiting the United States, Adolf Hitler came to power. Because of his Jewish background, Einstein did not return to Germany.[13] He settled in the United States and became an American citizen in 1940.[14] On the eve of World War II, he endorsed a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt alerting him to the potential German nuclear weapons program and recommending that the US begin similar research. Einstein supported the Allies, but generally denounced the idea of nuclear weapons.

Einstein was affiliated with the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, until his death in 1955. He published more than 300 scientific papers and more than 150 non-scientific works.[11][15] His intellectual achievements and originality have made the word "Einstein" synonymous with "genius".[16] Eugene Wigner compared him to his contemporaries, writing that "Einstein's understanding was deeper even than Jancsi von Neumann's. His mind was both more penetrating and more original than von Neumann's."[17]

Life and career

Early life and education

.jpg.webp)

Albert Einstein was born in Ulm, in the Kingdom of Württemberg in the German Empire, on 14 March 1879.[5] His parents were Hermann Einstein, a salesman and engineer, and Pauline Koch. In 1880, the family moved to Munich, where Einstein's father and his uncle Jakob founded Elektrotechnische Fabrik J. Einstein & Cie, a company that manufactured electrical equipment based on direct current.[5]

The Einsteins were non-observant Ashkenazi Jews, and Albert attended a Catholic elementary school in Munich, from the age of five, for three years. At the age of eight, he was transferred to the Luitpold Gymnasium (now known as the Albert Einstein Gymnasium), where he received advanced primary and secondary school education until he left the German Empire seven years later.[18]

In 1894, Hermann and Jakob's company lost a bid to supply the city of Munich with electrical lighting because they lacked the capital to convert their equipment from the direct current (DC) standard to the more efficient alternating current (AC) standard.[19] The loss forced the sale of the Munich factory. In search of business, the Einstein family moved to Italy, first to Milan and a few months later to Pavia. When the family moved to Pavia, Einstein, then 15, stayed in Munich to finish his studies at the Luitpold Gymnasium. His father intended for him to pursue electrical engineering, but Einstein clashed with the authorities and resented the school's regimen and teaching method. He later wrote that the spirit of learning and creative thought was lost in strict rote learning. At the end of December 1894, he traveled to Italy to join his family in Pavia, convincing the school to let him go by using a doctor's note.[20] During his time in Italy he wrote a short essay with the title "On the Investigation of the State of the Ether in a Magnetic Field".[21][22]

Einstein always excelled at math and physics from a young age, reaching a mathematical level years ahead of his peers. The 12-year-old Einstein taught himself algebra and Euclidean geometry over a single summer.[23] Einstein also independently discovered his own original proof of the Pythagorean theorem at age 12.[24] A family tutor Max Talmud says that after he had given the 12-year-old Einstein a geometry textbook, after a short time "[Einstein] had worked through the whole book. He thereupon devoted himself to higher mathematics... Soon the flight of his mathematical genius was so high I could not follow."[25] His passion for geometry and algebra led the 12-year-old to become convinced that nature could be understood as a "mathematical structure".[25] Einstein started teaching himself calculus at 12, and as a 14-year-old he says he had "mastered integral and differential calculus".[26]

.jpg.webp)

At age 13, when he had become more seriously interested in philosophy (and music),[27] Einstein was introduced to Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, and Kant became his favorite philosopher, his tutor stating: "At the time he was still a child, only thirteen years old, yet Kant's works, incomprehensible to ordinary mortals, seemed to be clear to him."[25]

In 1895, at the age of 16, Einstein took the entrance examinations for the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School in Zürich (later the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, ETH). He failed to reach the required standard in the general part of the examination,[28] but obtained exceptional grades in physics and mathematics.[29] On the advice of the principal of the polytechnic school, he attended the Argovian cantonal school (gymnasium) in Aarau, Switzerland, in 1895 and 1896 to complete his secondary schooling. While lodging with the family of professor Jost Winteler, he fell in love with Winteler's daughter, Marie. Albert's sister Maja later married Winteler's son Paul.[30] In January 1896, with his father's approval, Einstein renounced his citizenship in the German Kingdom of Württemberg to avoid military service.[31] In September 1896, he passed the Swiss Matura with mostly good grades, including a top grade of 6 in physics and mathematical subjects, on a scale of 1–6.[32] At 17, he enrolled in the four-year mathematics and physics teaching diploma program at the Zürich polytechnic school. Marie Winteler, who was a year older, moved to Olsberg, Switzerland, for a teaching post.[30]

Einstein's future wife, a 20-year-old Serbian named Mileva Marić, also enrolled at the polytechnic school that year. She was the only woman among the six students in the mathematics and physics section of the teaching diploma course. Over the next few years, Einstein's and Marić's friendship developed into romance, and they spent countless hours debating and reading books together on extra-curricular physics in which they were both interested. Einstein wrote in his letters to Marić that he preferred studying alongside her.[33] In 1900, Einstein passed the exams in Maths and Physics and was awarded the Federal teaching diploma.[34] There is eyewitness evidence and several letters over many years that indicate Marić might have collaborated with Einstein prior to his 1905 papers,[33][35][36] known as the Annus Mirabilis papers, and that they developed some of the concepts together during their studies, although some historians of physics who have studied the issue disagree that she made any substantive contributions.[37][38][39][40]

Marriages and children

Early correspondence between Einstein and Marić was discovered and published in 1987 which revealed that the couple had a daughter named "Lieserl", born in early 1902 in Novi Sad where Marić was staying with her parents. Marić returned to Switzerland without the child, whose real name and fate are unknown. The contents of Einstein's letter in September 1903 suggest that the girl was either given up for adoption or died of scarlet fever in infancy.[41][42]

Einstein and Marić married in January 1903. In May 1904, their son Hans Albert Einstein was born in Bern, Switzerland. Their son Eduard was born in Zürich in July 1910. The couple moved to Berlin in April 1914, but Marić returned to Zürich with their sons after learning that despite their close relationship before,[33] Einstein's chief romantic attraction was now his cousin Elsa Löwenthal;[43] she was his first cousin maternally and second cousin paternally.[44] They divorced on 14 February 1919, having lived apart for five years.[45][46] As part of the divorce settlement, Einstein transferred his Nobel Prize fund to Marić when he won it.[47] Eduard had a breakdown at about age 20 and was diagnosed with schizophrenia.[48] His mother cared for him and he was also committed to asylums for several periods, finally being committed permanently after her death.[49]

In letters revealed in 2015, Einstein wrote to his early love Marie Winteler about his marriage and his strong feelings for her. He wrote in 1910, while his wife was pregnant with their second child: "I think of you in heartfelt love every spare minute and am so unhappy as only a man can be." He spoke about a "misguided love" and a "missed life" regarding his love for Marie.[50]

Einstein married Elsa Löwenthal in 1919,[51][52] after having a relationship with her since 1912.[44] They emigrated to the United States in 1933. Elsa was diagnosed with heart and kidney problems in 1935 and died in December 1936.[53]

In 1923, Einstein fell in love with a secretary named Betty Neumann, the niece of a close friend, Hans Mühsam.[54][55][56][57] In a volume of letters released by Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 2006,[58] Einstein described about six women, including Margarete Lebach (a blonde Austrian), Estella Katzenellenbogen (the rich owner of a florist business), Toni Mendel (a wealthy Jewish widow) and Ethel Michanowski (a Berlin socialite), with whom he spent time and from whom he received gifts while being married to Elsa.[59][60] Later, after the death of his second wife Elsa, Einstein was briefly in a relationship with Margarita Konenkova.[61] Konenkova was a Russian spy who was married to the noted Russian sculptor Sergei Konenkov (who created the bronze bust of Einstein at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton).[62][63]

Friends

Among Einstein's well-known friends were Michele Besso, Paul Ehrenfest, Marcel Grossmann, János Plesch, Daniel Q. Posin, Maurice Solovine, Stephen Samuel Wise[64] and Fritz Haber.[65]

Patent office

After graduating in 1900, Einstein spent almost two frustrating years searching for a teaching post. He acquired Swiss citizenship in February 1901,[66] but for medical reasons was not conscripted. With the help of Marcel Grossmann's father, he secured a job in Bern at the Federal Office for Intellectual Property, the patent office,[67][68] as an assistant examiner – level III.[69][70]

Einstein evaluated patent applications for a variety of devices including a gravel sorter and an electromechanical typewriter.[70] In 1903, his position at the Swiss Patent Office became permanent, although he was passed over for promotion until he "fully mastered machine technology".[71]

Much of his work at the patent office related to questions about transmission of electric signals and electrical–mechanical synchronization of time, two technical problems that show up conspicuously in the thought experiments that eventually led Einstein to his radical conclusions about the nature of light and the fundamental connection between space and time.[72]

With a few friends he had met in Bern, Einstein started a small discussion group in 1902, self-mockingly named "The Olympia Academy", which met regularly to discuss science and philosophy. Sometimes they were joined by Mileva who attentively listened but did not participate.[73] Their readings included the works of Henri Poincaré, Ernst Mach, and David Hume, which influenced his scientific and philosophical outlook.[74]

First scientific papers

In 1900, Einstein's paper "Folgerungen aus den Capillaritätserscheinungen" ("Conclusions from the Capillarity Phenomena") was published in the journal Annalen der Physik.[75][76] On 30 April 1905, Einstein completed his thesis,[77] with Alfred Kleiner, Professor of Experimental Physics, serving as pro-forma advisor. As a result, Einstein was awarded a PhD by the University of Zürich, with his dissertation A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions.[77][78]

Also in 1905, which has been called Einstein's annus mirabilis (amazing year), he published four groundbreaking papers, on the photoelectric effect, Brownian motion, special relativity, and the equivalence of mass and energy, which were to bring him to the notice of the academic world, at the age of 26.

Academic career

By 1908, he was recognized as a leading scientist and was appointed lecturer at the University of Bern. The following year, after he gave a lecture on electrodynamics and the relativity principle at the University of Zurich, Alfred Kleiner recommended him to the faculty for a newly created professorship in theoretical physics. Einstein was appointed associate professor in 1909.[79]

Einstein became a full professor at the German Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague in April 1911, accepting Austrian citizenship in the Austro-Hungarian Empire to do so.[80][81] During his Prague stay, he wrote 11 scientific works, five of them on radiation mathematics and on the quantum theory of solids. In July 1912, he returned to his alma mater in Zürich. From 1912 until 1914, he was a professor of theoretical physics at the ETH Zurich, where he taught analytical mechanics and thermodynamics. He also studied continuum mechanics, the molecular theory of heat, and the problem of gravitation, on which he worked with mathematician and friend Marcel Grossmann.[82]

When the ″Manifesto of the Ninety-Three″ was published in October 1914—a document signed by a host of prominent German intellectuals that justified Germany's militarism and position during the First World War—Einstein was one of the few German intellectuals to rebut its contents and sign the pacifistic ″Manifesto to the Europeans″.[83]

On 3 July 1913, he was voted for membership in the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin. Max Planck and Walther Nernst visited him the next week in Zurich to persuade him to join the academy, additionally offering him the post of director at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, which was soon to be established.[85] Membership in the academy included paid salary and professorship without teaching duties at Humboldt University of Berlin. He was officially elected to the academy on 24 July, and he moved to Berlin the following year. His decision to move to Berlin was also influenced by the prospect of living near his cousin Elsa, with whom he had started a romantic affair. He joined the academy and thus Berlin University on 1 April 1914.[86] As World War I broke out that year, the plan for Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics was aborted. The institute was established on 1 October 1917, with Einstein as its director.[87] In 1916, Einstein was elected president of the German Physical Society (1916–1918).[88]

.png.webp)

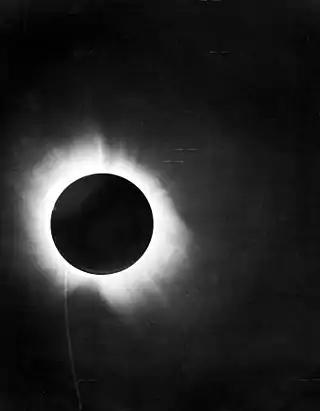

Based on calculations Einstein had made in 1911 using his new theory of general relativity, light from another star should be bent by the Sun's gravity. In 1919, that prediction was confirmed by Sir Arthur Eddington during the solar eclipse of 29 May 1919. Those observations were published in the international media, making Einstein world-famous. On 7 November 1919, the leading British newspaper The Times printed a banner headline that read: "Revolution in Science – New Theory of the Universe – Newtonian Ideas Overthrown".[89]

In 1920, he became a Foreign Member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.[90] In 1922, he was awarded the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect".[10] While the general theory of relativity was still considered somewhat controversial, the citation also does not treat even the cited photoelectric work as an explanation but merely as a discovery of the law, as the idea of photons was considered outlandish and did not receive universal acceptance until the 1924 derivation of the Planck spectrum by S. N. Bose. Einstein was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1921.[3] He also received the Copley Medal from the Royal Society in 1925.[3]

1921–1922: Travels abroad

Einstein visited New York City for the first time on 2 April 1921, where he received an official welcome by Mayor John Francis Hylan, followed by three weeks of lectures and receptions. He went on to deliver several lectures at Columbia University and Princeton University, and in Washington, he accompanied representatives of the National Academy of Science on a visit to the White House. On his return to Europe he was the guest of the British statesman and philosopher Viscount Haldane in London, where he met several renowned scientific, intellectual and political figures, and delivered a lecture at King's College London.[91][92]

He also published an essay, "My First Impression of the U.S.A.", in July 1921, in which he tried briefly to describe some characteristics of Americans, much as had Alexis de Tocqueville, who published his own impressions in Democracy in America (1835).[93] For some of his observations, Einstein was clearly surprised: "What strikes a visitor is the joyous, positive attitude to life ... The American is friendly, self-confident, optimistic, and without envy."[94]

In 1922, his travels took him to Asia and later to Palestine, as part of a six-month excursion and speaking tour, as he visited Singapore, Ceylon and Japan, where he gave a series of lectures to thousands of Japanese. After his first public lecture, he met the emperor and empress at the Imperial Palace, where thousands came to watch. In a letter to his sons, he described his impression of the Japanese as being modest, intelligent, considerate, and having a true feel for art.[95] In his own travel diaries from his 1922–23 visit to Asia, he expresses some views on the Chinese, Japanese and Indian people, which have been described as xenophobic and racist judgments when they were rediscovered in 2018.[96][97]

Because of Einstein's travels to the Far East, he was unable to personally accept the Nobel Prize for Physics at the Stockholm award ceremony in December 1922. In his place, the banquet speech was made by a German diplomat, who praised Einstein not only as a scientist but also as an international peacemaker and activist.[98]

On his return voyage, he visited Palestine for 12 days, his only visit to that region. He was greeted as if he were a head of state, rather than a physicist, which included a cannon salute upon arriving at the home of the British high commissioner, Sir Herbert Samuel. During one reception, the building was stormed by people who wanted to see and hear him. In Einstein's talk to the audience, he expressed happiness that the Jewish people were beginning to be recognized as a force in the world.[99]

Einstein visited Spain for two weeks in 1923, where he briefly met Santiago Ramón y Cajal and also received a diploma from King Alfonso XIII naming him a member of the Spanish Academy of Sciences.[100]

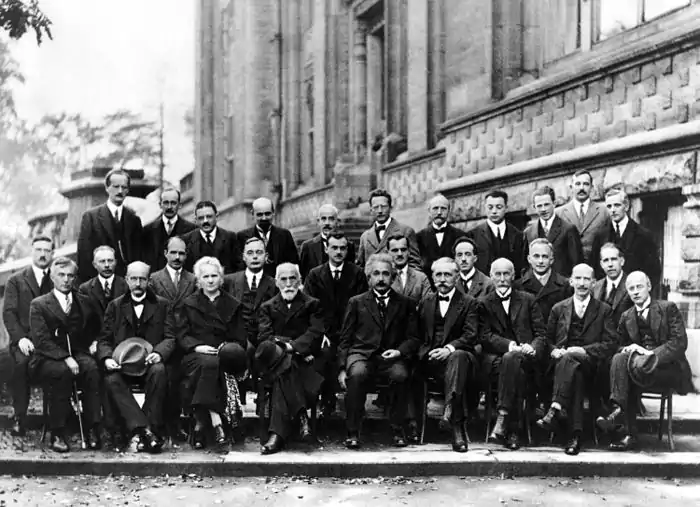

From 1922 to 1932, Einstein was a member of the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations in Geneva (with a few months of interruption in 1923–1924),[101] a body created to promote international exchange between scientists, researchers, teachers, artists and intellectuals.[102] Originally slated to serve as the Swiss delegate, Secretary-General Eric Drummond was persuaded by Catholic activists Oskar Halecki and Giuseppe Motta to instead have him become the German delegate, thus allowing Gonzague de Reynold to take the Swiss spot, from which he promoted traditionalist Catholic values.[103] Einstein's former physics professor Hendrik Lorentz and the Polish chemist Marie Curie were also members of the committee.

1930–1931: Travel to the US

In December 1930, Einstein visited America for the second time, originally intended as a two-month working visit as a research fellow at the California Institute of Technology. After the national attention he received during his first trip to the US, he and his arrangers aimed to protect his privacy. Although swamped with telegrams and invitations to receive awards or speak publicly, he declined them all.[104]

After arriving in New York City, Einstein was taken to various places and events, including Chinatown, a lunch with the editors of The New York Times, and a performance of Carmen at the Metropolitan Opera, where he was cheered by the audience on his arrival. During the days following, he was given the keys to the city by Mayor Jimmy Walker and met the president of Columbia University, who described Einstein as "the ruling monarch of the mind".[105] Harry Emerson Fosdick, pastor at New York's Riverside Church, gave Einstein a tour of the church and showed him a full-size statue that the church made of Einstein, standing at the entrance.[105] Also during his stay in New York, he joined a crowd of 15,000 people at Madison Square Garden during a Hanukkah celebration.[105]

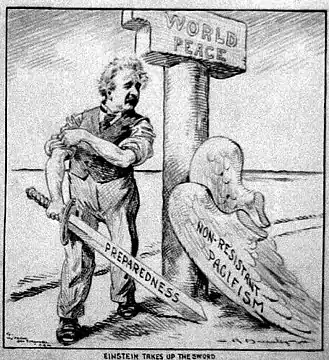

Einstein next traveled to California, where he met Caltech president and Nobel laureate Robert A. Millikan. His friendship with Millikan was "awkward", as Millikan "had a penchant for patriotic militarism", where Einstein was a pronounced pacifist.[106] During an address to Caltech's students, Einstein noted that science was often inclined to do more harm than good.[107]

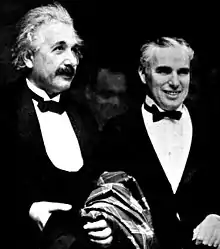

This aversion to war also led Einstein to befriend author Upton Sinclair and film star Charlie Chaplin, both noted for their pacifism. Carl Laemmle, head of Universal Studios, gave Einstein a tour of his studio and introduced him to Chaplin. They had an instant rapport, with Chaplin inviting Einstein and his wife, Elsa, to his home for dinner. Chaplin said Einstein's outward persona, calm and gentle, seemed to conceal a "highly emotional temperament", from which came his "extraordinary intellectual energy".[108]

Chaplin's film, City Lights, was to premiere a few days later in Hollywood, and Chaplin invited Einstein and Elsa to join him as his special guests. Walter Isaacson, Einstein's biographer, described this as "one of the most memorable scenes in the new era of celebrity".[107] Chaplin visited Einstein at his home on a later trip to Berlin and recalled his "modest little flat" and the piano at which he had begun writing his theory. Chaplin speculated that it was "possibly used as kindling wood by the Nazis".[109]

1933: Emigration to the US

In February 1933, while on a visit to the United States, Einstein knew he could not return to Germany with the rise to power of the Nazis under Germany's new chancellor, Adolf Hitler.[110][111]

While at American universities in early 1933, he undertook his third two-month visiting professorship at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. In February and March 1933, the Gestapo repeatedly raided his family's apartment in Berlin.[112]

He and his wife Elsa returned to Europe in March, and during the trip, they learned that the German Reichstag passed the Enabling Act, which was passed on 23 March and transformed Hitler's government into a de facto legal dictatorship and that they would not be able to proceed to Berlin. Later on they heard that their cottage was raided by the Nazis and his personal sailboat confiscated. Upon landing in Antwerp, Belgium on 28 March, he immediately went to the German consulate and surrendered his passport, formally renouncing his German citizenship.[113] The Nazis later sold his boat and converted his cottage into a Hitler Youth camp.[114]

Refugee status

In April 1933, Einstein discovered that the new German government had passed laws barring Jews from holding any official positions, including teaching at universities.[113] Historian Gerald Holton describes how, with "virtually no audible protest being raised by their colleagues", thousands of Jewish scientists were suddenly forced to give up their university positions and their names were removed from the rolls of institutions where they were employed.[115]

A month later, Einstein's works were among those targeted by the German Student Union in the Nazi book burnings, with Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels proclaiming, "Jewish intellectualism is dead."[113] One German magazine included him in a list of enemies of the German regime with the phrase, "not yet hanged", offering a $5,000 bounty on his head.[113][116] In a subsequent letter to physicist and friend Max Born, who had already emigrated from Germany to England, Einstein wrote, "... I must confess that the degree of their brutality and cowardice came as something of a surprise."[113] After moving to the US, he described the book burnings as a "spontaneous emotional outburst" by those who "shun popular enlightenment", and "more than anything else in the world, fear the influence of men of intellectual independence".[117]

Einstein was now without a permanent home, unsure where he would live and work, and equally worried about the fate of countless other scientists still in Germany. He rented a house in De Haan, Belgium, where he lived for a few months. In late July 1933, he went to England for about six weeks at the personal invitation of British naval officer Commander Oliver Locker-Lampson, who had become friends with Einstein in the preceding years. Locker-Lampson invited him to stay near his Cromer home in a wooden cabin on Roughton Heath in the Parish of Roughton, Norfolk. To protect Einstein, Locker-Lampson had two bodyguards watch over him at his secluded cabin, with a photo of them carrying shotguns and guarding Einstein, published in the Daily Herald on 24 July 1933.[118][119]

Locker-Lampson took Einstein to meet Winston Churchill at his home, and later, Austen Chamberlain and former Prime Minister Lloyd George.[120] Einstein asked them to help bring Jewish scientists out of Germany. British historian Martin Gilbert notes that Churchill responded immediately, and sent his friend, physicist Frederick Lindemann, to Germany to seek out Jewish scientists and place them in British universities.[121] Churchill later observed that as a result of Germany having driven the Jews out, they had lowered their "technical standards" and put the Allies' technology ahead of theirs.[121]

Einstein later contacted leaders of other nations, including Turkey's Prime Minister, İsmet İnönü, to whom he wrote in September 1933 requesting placement of unemployed German-Jewish scientists. As a result of Einstein's letter, Jewish invitees to Turkey eventually totaled over "1,000 saved individuals".[122]

Locker-Lampson also submitted a bill to parliament to extend British citizenship to Einstein, during which period Einstein made a number of public appearances describing the crisis brewing in Europe.[123] In one of his speeches he denounced Germany's treatment of Jews, while at the same time he introduced a bill promoting Jewish citizenship in Palestine, as they were being denied citizenship elsewhere.[124] In his speech he described Einstein as a "citizen of the world" who should be offered a temporary shelter in the UK.[note 3][125] Both bills failed, however, and Einstein then accepted an earlier offer from the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton, New Jersey, US, to become a resident scholar.[123]

Resident scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study

In October 1933, Einstein returned to the US and took up a position at the Institute for Advanced Study,[123][126] noted for having become a refuge for scientists fleeing Nazi Germany.[127] At the time, most American universities, including Harvard, Princeton and Yale, had minimal or no Jewish faculty or students, as a result of their Jewish quotas, which lasted until the late 1940s.[127]

Einstein was still undecided on his future. He had offers from several European universities, including Christ Church, Oxford where he stayed for three short periods between May 1931 and June 1933 and was offered a 5-year studentship,[128][129] but in 1935, he arrived at the decision to remain permanently in the United States and apply for citizenship.[123][130]

Einstein's affiliation with the Institute for Advanced Study would last until his death in 1955.[131] He was one of the four first selected (two of the others being John von Neumann and Kurt Gödel) at the new Institute, where he soon developed a close friendship with Gödel. The two would take long walks together discussing their work. Bruria Kaufman, his assistant, later became a physicist. During this period, Einstein tried to develop a unified field theory and to refute the accepted interpretation of quantum physics, both unsuccessfully.

World War II and the Manhattan Project

In 1939, a group of Hungarian scientists that included émigré physicist Leó Szilárd attempted to alert Washington to ongoing Nazi atomic bomb research. The group's warnings were discounted. Einstein and Szilárd, along with other refugees such as Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner, "regarded it as their responsibility to alert Americans to the possibility that German scientists might win the race to build an atomic bomb, and to warn that Hitler would be more than willing to resort to such a weapon."[132][133] To make certain the US was aware of the danger, in July 1939, a few months before the beginning of World War II in Europe, Szilárd and Wigner visited Einstein to explain the possibility of atomic bombs, which Einstein, a pacifist, said he had never considered.[134] He was asked to lend his support by writing a letter, with Szilárd, to President Roosevelt, recommending the US pay attention and engage in its own nuclear weapons research.

The letter is believed to be "arguably the key stimulus for the U.S. adoption of serious investigations into nuclear weapons on the eve of the U.S. entry into World War II".[135] In addition to the letter, Einstein used his connections with the Belgian Royal Family[136] and the Belgian queen mother to get access with a personal envoy to the White House's Oval Office. Some say that as a result of Einstein's letter and his meetings with Roosevelt, the US entered the "race" to develop the bomb, drawing on its "immense material, financial, and scientific resources" to initiate the Manhattan Project.

For Einstein, "war was a disease ... [and] he called for resistance to war." By signing the letter to Roosevelt, some argue he went against his pacifist principles.[137] In 1954, a year before his death, Einstein said to his old friend, Linus Pauling, "I made one great mistake in my life—when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt recommending that atom bombs be made; but there was some justification—the danger that the Germans would make them ..."[138] In 1955, Einstein and ten other intellectuals and scientists, including British philosopher Bertrand Russell, signed a manifesto highlighting the danger of nuclear weapons.

US citizenship

Einstein became an American citizen in 1940. Not long after settling into his career at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, he expressed his appreciation of the meritocracy in American culture when compared to Europe. He recognized the "right of individuals to say and think what they pleased", without social barriers, and as a result, individuals were encouraged, he said, to be more creative, a trait he valued from his own early education.[139]

Einstein joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Princeton, where he campaigned for the civil rights of African Americans. He considered racism America's "worst disease",[116] seeing it as "handed down from one generation to the next".[140] As part of his involvement, he corresponded with civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois and was prepared to testify on his behalf during his trial in 1951.[141] When Einstein offered to be a character witness for Du Bois, the judge decided to drop the case.[142]

In 1946 Einstein visited Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, a historically black college, where he was awarded an honorary degree. Lincoln was the first university in the United States to grant college degrees to African Americans; alumni include Langston Hughes and Thurgood Marshall. Einstein gave a speech about racism in America, adding, "I do not intend to be quiet about it."[143] A resident of Princeton recalls that Einstein had once paid the college tuition for a black student.[142]

Assisting Zionist causes

Einstein was a figurehead leader in helping establish the Hebrew University of Jerusalem,[144] which opened in 1925 and was among its first Board of Governors. Earlier, in 1921, he was asked by the biochemist and president of the World Zionist Organization, Chaim Weizmann, to help raise funds for the planned university.[145] He also submitted various suggestions as to its initial programs.

Among those, he advised first creating an Institute of Agriculture in order to settle the undeveloped land. That should be followed, he suggested, by a Chemical Institute and an Institute of Microbiology, to fight the various ongoing epidemics such as malaria, which he called an "evil" that was undermining a third of the country's development.[146] Establishing an Oriental Studies Institute, to include language courses given in both Hebrew and Arabic, for scientific exploration of the country and its historical monuments, was also important.[147]

Chaim Weizmann later became Israel's first president. Upon his death while in office in November 1952 and at the urging of Ezriel Carlebach, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion offered Einstein the position of President of Israel, a mostly ceremonial post.[148][149] The offer was presented by Israel's ambassador in Washington, Abba Eban, who explained that the offer "embodies the deepest respect which the Jewish people can repose in any of its sons".[150] Einstein declined, and wrote in his response that he was "deeply moved", and "at once saddened and ashamed" that he could not accept it.[150]

Love of music

Einstein developed an appreciation for music at an early age. In his late journals he wrote: "If I were not a physicist, I would probably be a musician. I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music... I get most joy in life out of music."[151][152]

His mother played the piano reasonably well and wanted her son to learn the violin, not only to instill in him a love of music but also to help him assimilate into German culture. According to conductor Leon Botstein, Einstein began playing when he was 5. However, he did not enjoy it at that age.[153]

When he turned 13, he discovered the violin sonatas of Mozart, whereupon he became enamored of Mozart's compositions and studied music more willingly. Einstein taught himself to play without "ever practicing systematically". He said that "love is a better teacher than a sense of duty."[153] At age 17, he was heard by a school examiner in Aarau while playing Beethoven's violin sonatas. The examiner stated afterward that his playing was "remarkable and revealing of 'great insight'". What struck the examiner, writes Botstein, was that Einstein "displayed a deep love of the music, a quality that was and remains in short supply. Music possessed an unusual meaning for this student."[153]

Music took on a pivotal and permanent role in Einstein's life from that period on. Although the idea of becoming a professional musician himself was not on his mind at any time, among those with whom Einstein played chamber music were a few professionals, and he performed for private audiences and friends. Chamber music had also become a regular part of his social life while living in Bern, Zürich, and Berlin, where he played with Max Planck and his son, among others. He is sometimes erroneously credited as the editor of the 1937 edition of the Köchel catalog of Mozart's work; that edition was prepared by Alfred Einstein, who may have been a distant relation.[154][155]

In 1931, while engaged in research at the California Institute of Technology, he visited the Zoellner family conservatory in Los Angeles, where he played some of Beethoven and Mozart's works with members of the Zoellner Quartet.[156][157] Near the end of his life, when the young Juilliard Quartet visited him in Princeton, he played his violin with them, and the quartet was "impressed by Einstein's level of coordination and intonation".[153]

Political and religious views

In 1918, Einstein was one of the founding members of the German Democratic Party, a liberal party.[158] However, later in his life, Einstein's political view was in favor of socialism and critical of capitalism, which he detailed in his essays such as "Why Socialism?"[159][160] His opinions on the Bolsheviks also changed with time. In 1925, he criticized them for not having a 'well-regulated system of government' and called their rule a 'regime of terror and a tragedy in human history'. He later adopted a more balanced view, criticizing their methods but praising them, which is shown by his 1929 remark on Vladimir Lenin: "In Lenin I honor a man, who in total sacrifice of his own person has committed his entire energy to realizing social justice. I do not find his methods advisable. One thing is certain, however: men like him are the guardians and renewers of mankind's conscience."[161] Einstein offered and was called on to give judgments and opinions on matters often unrelated to theoretical physics or mathematics.[123] He strongly advocated the idea of a democratic global government that would check the power of nation-states in the framework of a world federation.[162] The FBI created a secret dossier on Einstein in 1932, and by the time of his death his FBI file was 1,427 pages long.[163]

Einstein was deeply impressed by Mahatma Gandhi, with whom he exchanged written letters. He described Gandhi as "a role model for the generations to come".[164]

Einstein spoke of his spiritual outlook in a wide array of original writings and interviews.[165] Einstein stated that he had sympathy for the impersonal pantheistic God of Baruch Spinoza's philosophy.[166] He did not believe in a personal god who concerns himself with fates and actions of human beings, a view which he described as naïve.[167] He clarified, however, that "I am not an atheist",[168] preferring to call himself an agnostic,[169][170] or a "deeply religious nonbeliever".[167] When asked if he believed in an afterlife, Einstein replied, "No. And one life is enough for me."[171]

Einstein was primarily affiliated with non-religious humanist and Ethical Culture groups in both the UK and US. He served on the advisory board of the First Humanist Society of New York,[172] and was an honorary associate of the Rationalist Association, which publishes New Humanist in Britain. For the 75th anniversary of the New York Society for Ethical Culture, he stated that the idea of Ethical Culture embodied his personal conception of what is most valuable and enduring in religious idealism. He observed, "Without 'ethical culture' there is no salvation for humanity."[173]

In a German-language letter to philosopher Eric Gutkind, dated 3 January 1954, Einstein wrote:

The word God is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of honorable, but still primitive legends which are nevertheless pretty childish. No interpretation no matter how subtle can (for me) change this. ... For me the Jewish religion like all other religions is an incarnation of the most childish superstitions. And the Jewish people to whom I gladly belong and with whose mentality I have a deep affinity have no different quality for me than all other people. ... I cannot see anything 'chosen' about them.[174]

Death

On 17 April 1955, Einstein experienced internal bleeding caused by the rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, which had previously been reinforced surgically by Rudolph Nissen in 1948.[175] He took the draft of a speech he was preparing for a television appearance commemorating the State of Israel's seventh anniversary with him to the hospital, but he did not live long enough to complete it.[176]

Einstein refused surgery, saying, "I want to go when I want. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share; it is time to go. I will do it elegantly."[177] He died in Princeton Hospital early the next morning at the age of 76, having continued to work until near the end.[178]

During the autopsy, the pathologist of Princeton Hospital, Thomas Stoltz Harvey, removed Einstein's brain for preservation without the permission of his family, in the hope that the neuroscience of the future would be able to discover what made Einstein so intelligent.[179] Einstein's remains were cremated and his ashes were scattered at an undisclosed location.[180][181]

In a memorial lecture delivered on 13 December 1965, at UNESCO headquarters, nuclear physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer summarized his impression of Einstein as a person: "He was almost wholly without sophistication and wholly without worldliness ... There was always with him a wonderful purity at once childlike and profoundly stubborn."[182]

Scientific career

Throughout his life, Einstein published hundreds of books and articles.[5][15] He published more than 300 scientific papers and 150 non-scientific ones.[11][15] On 5 December 2014, universities and archives announced the release of Einstein's papers, comprising more than 30,000 unique documents.[183][184] Einstein's intellectual achievements and originality have made the word "Einstein" synonymous with "genius".[16] In addition to the work he did by himself he also collaborated with other scientists on additional projects including the Bose–Einstein statistics, the Einstein refrigerator and others.[185][186]

1905 – Annus Mirabilis papers

The Annus Mirabilis papers are four articles pertaining to the photoelectric effect (which gave rise to quantum theory), Brownian motion, the special theory of relativity, and E = mc2 that Einstein published in the Annalen der Physik scientific journal in 1905. These four works contributed substantially to the foundation of modern physics and changed views on space, time, and matter. The four papers are:

| Title (translated) | Area of focus | Received | Published | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "On a Heuristic Viewpoint Concerning the Production and Transformation of Light"[187] | Photoelectric effect | 18 March | 9 June | Resolved an unsolved puzzle by suggesting that energy is exchanged only in discrete amounts (quanta).[188] This idea was pivotal to the early development of quantum theory.[189] |

| "On the Motion of Small Particles Suspended in a Stationary Liquid, as Required by the Molecular Kinetic Theory of Heat"[190] | Brownian motion | 11 May | 18 July | Explained empirical evidence for the atomic theory, supporting the application of statistical physics. |

| "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies"[191] | Special relativity | 30 June | 26 September | Reconciled Maxwell's equations for electricity and magnetism with the laws of mechanics by introducing changes to mechanics, resulting from analysis based on empirical evidence that the speed of light is independent of the motion of the observer.[192] Discredited the concept of a "luminiferous ether".[193] |

| "Does the Inertia of a Body Depend Upon Its Energy Content?"[194] | Matter–energy equivalence | 27 September | 21 November | Equivalence of matter and energy, E = mc2 (and by implication, the ability of gravity to "bend" light), the existence of "rest energy", and the basis of nuclear energy. |

Thermodynamic fluctuations and statistical physics

Einstein's first paper[75][195] submitted in 1900 to Annalen der Physik was on capillary attraction. It was published in 1901 with the title "Folgerungen aus den Capillaritätserscheinungen", which translates as "Conclusions from the capillarity phenomena". Two papers he published in 1902–1903 (thermodynamics) attempted to interpret atomic phenomena from a statistical point of view. These papers were the foundation for the 1905 paper on Brownian motion, which showed that Brownian movement can be construed as firm evidence that molecules exist. His research in 1903 and 1904 was mainly concerned with the effect of finite atomic size on diffusion phenomena.[195]

Theory of critical opalescence

Einstein returned to the problem of thermodynamic fluctuations, giving a treatment of the density variations in a fluid at its critical point. Ordinarily the density fluctuations are controlled by the second derivative of the free energy with respect to the density. At the critical point, this derivative is zero, leading to large fluctuations. The effect of density fluctuations is that light of all wavelengths is scattered, making the fluid look milky white. Einstein relates this to Rayleigh scattering, which is what happens when the fluctuation size is much smaller than the wavelength, and which explains why the sky is blue.[196] Einstein quantitatively derived critical opalescence from a treatment of density fluctuations, and demonstrated how both the effect and Rayleigh scattering originate from the atomistic constitution of matter.

Special relativity

Einstein's "Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper"[191] ("On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies") was received on 30 June 1905 and published 26 September of that same year. It reconciled conflicts between Maxwell's equations (the laws of electricity and magnetism) and the laws of Newtonian mechanics by introducing changes to the laws of mechanics.[197] Observationally, the effects of these changes are most apparent at high speeds (where objects are moving at speeds close to the speed of light). The theory developed in this paper later became known as Einstein's special theory of relativity. There is evidence from Einstein's writings that he collaborated with his first wife, Mileva Marić, on this work. The decision to publish only under his name seems to have been mutual, but the exact reason is unknown.[33]

This paper predicted that, when measured in the frame of a relatively moving observer, a clock carried by a moving body would appear to slow down, and the body itself would contract in its direction of motion. This paper also argued that the idea of a luminiferous aether—one of the leading theoretical entities in physics at the time—was superfluous.[note 4]

In his paper on mass–energy equivalence, Einstein produced E = mc2 as a consequence of his special relativity equations.[198] Einstein's 1905 work on relativity remained controversial for many years, but was accepted by leading physicists, starting with Max Planck.[note 5][199]

Einstein originally framed special relativity in terms of kinematics (the study of moving bodies). In 1908, Hermann Minkowski reinterpreted special relativity in geometric terms as a theory of spacetime. Einstein adopted Minkowski's formalism in his 1915 general theory of relativity.[200]

General relativity and the equivalence principle

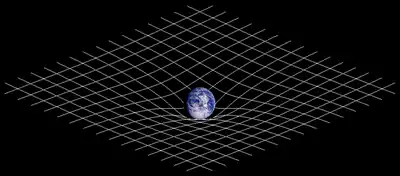

General relativity (GR) is a theory of gravitation that was developed by Einstein between 1907 and 1915. According to general relativity, the observed gravitational attraction between masses results from the warping of space and time by those masses. General relativity has developed into an essential tool in modern astrophysics. It provides the foundation for the current understanding of black holes, regions of space where gravitational attraction is so strong that not even light can escape.

As Einstein later said, the reason for the development of general relativity was that the preference of inertial motions within special relativity was unsatisfactory, while a theory which from the outset prefers no state of motion (even accelerated ones) should appear more satisfactory.[201] Consequently, in 1907 he published an article on acceleration under special relativity. In that article titled "On the Relativity Principle and the Conclusions Drawn from It", he argued that free fall is really inertial motion, and that for a free-falling observer the rules of special relativity must apply. This argument is called the equivalence principle. In the same article, Einstein also predicted the phenomena of gravitational time dilation, gravitational redshift and deflection of light.[202][203]

In 1911, Einstein published another article "On the Influence of Gravitation on the Propagation of Light" expanding on the 1907 article, in which he estimated the amount of deflection of light by massive bodies. Thus, the theoretical prediction of general relativity could for the first time be tested experimentally.[204]

Gravitational waves

In 1916, Einstein predicted gravitational waves,[205][206] ripples in the curvature of spacetime which propagate as waves, traveling outward from the source, transporting energy as gravitational radiation. The existence of gravitational waves is possible under general relativity due to its Lorentz invariance which brings the concept of a finite speed of propagation of the physical interactions of gravity with it. By contrast, gravitational waves cannot exist in the Newtonian theory of gravitation, which postulates that the physical interactions of gravity propagate at infinite speed.

The first, indirect, detection of gravitational waves came in the 1970s through observation of a pair of closely orbiting neutron stars, PSR B1913+16.[207] The explanation of the decay in their orbital period was that they were emitting gravitational waves.[207][208] Einstein's prediction was confirmed on 11 February 2016, when researchers at LIGO published the first observation of gravitational waves,[209] detected on Earth on 14 September 2015, nearly one hundred years after the prediction.[207][210][211][212][213]

Hole argument and Entwurf theory

While developing general relativity, Einstein became confused about the gauge invariance in the theory. He formulated an argument that led him to conclude that a general relativistic field theory is impossible. He gave up looking for fully generally covariant tensor equations and searched for equations that would be invariant under general linear transformations only.

In June 1913, the Entwurf ('draft') theory was the result of these investigations. As its name suggests, it was a sketch of a theory, less elegant and more difficult than general relativity, with the equations of motion supplemented by additional gauge fixing conditions. After more than two years of intensive work, Einstein realized that the hole argument was mistaken[214] and abandoned the theory in November 1915.

Physical cosmology

In 1917, Einstein applied the general theory of relativity to the structure of the universe as a whole.[215] He discovered that the general field equations predicted a universe that was dynamic, either contracting or expanding. As observational evidence for a dynamic universe was not known at the time, Einstein introduced a new term, the cosmological constant, to the field equations, in order to allow the theory to predict a static universe. The modified field equations predicted a static universe of closed curvature, in accordance with Einstein's understanding of Mach's principle in these years. This model became known as the Einstein World or Einstein's static universe.[216][217]

Following the discovery of the recession of the nebulae by Edwin Hubble in 1929, Einstein abandoned his static model of the universe, and proposed two dynamic models of the cosmos, The Friedmann-Einstein universe of 1931[218][219] and the Einstein–de Sitter universe of 1932.[220][221] In each of these models, Einstein discarded the cosmological constant, claiming that it was "in any case theoretically unsatisfactory".[218][219][222]

In many Einstein biographies, it is claimed that Einstein referred to the cosmological constant in later years as his "biggest blunder". The astrophysicist Mario Livio has recently cast doubt on this claim, suggesting that it may be exaggerated.[223]

In late 2013, a team led by the Irish physicist Cormac O'Raifeartaigh discovered evidence that, shortly after learning of Hubble's observations of the recession of the nebulae, Einstein considered a steady-state model of the universe.[224][225] In a hitherto overlooked manuscript, apparently written in early 1931, Einstein explored a model of the expanding universe in which the density of matter remains constant due to a continuous creation of matter, a process he associated with the cosmological constant.[226][227] As he stated in the paper, "In what follows, I would like to draw attention to a solution to equation (1) that can account for Hubbel's [sic] facts, and in which the density is constant over time" ... "If one considers a physically bounded volume, particles of matter will be continually leaving it. For the density to remain constant, new particles of matter must be continually formed in the volume from space."

It thus appears that Einstein considered a steady-state model of the expanding universe many years before Hoyle, Bondi and Gold.[228][229] However, Einstein's steady-state model contained a fundamental flaw and he quickly abandoned the idea.[226][227][230]

Energy momentum pseudotensor

General relativity includes a dynamical spacetime, so it is difficult to see how to identify the conserved energy and momentum. Noether's theorem allows these quantities to be determined from a Lagrangian with translation invariance, but general covariance makes translation invariance into something of a gauge symmetry. The energy and momentum derived within general relativity by Noether's prescriptions do not make a real tensor for this reason.

Einstein argued that this is true for a fundamental reason: the gravitational field could be made to vanish by a choice of coordinates. He maintained that the non-covariant energy momentum pseudotensor was, in fact, the best description of the energy momentum distribution in a gravitational field. This approach has been echoed by Lev Landau and Evgeny Lifshitz, and others, and has become standard.

The use of non-covariant objects like pseudotensors was heavily criticized in 1917 by Erwin Schrödinger and others.

Wormholes

In 1935, Einstein collaborated with Nathan Rosen to produce a model of a wormhole, often called Einstein–Rosen bridges.[231][232] His motivation was to model elementary particles with charge as a solution of gravitational field equations, in line with the program outlined in the paper "Do Gravitational Fields play an Important Role in the Constitution of the Elementary Particles?". These solutions cut and pasted Schwarzschild black holes to make a bridge between two patches.[233]

If one end of a wormhole was positively charged, the other end would be negatively charged. These properties led Einstein to believe that pairs of particles and antiparticles could be described in this way.

Einstein–Cartan theory

In order to incorporate spinning point particles into general relativity, the affine connection needed to be generalized to include an antisymmetric part, called the torsion. This modification was made by Einstein and Cartan in the 1920s.

Equations of motion

The theory of general relativity has a fundamental law—the Einstein field equations, which describe how space curves. The geodesic equation, which describes how particles move, may be derived from the Einstein field equations.

Since the equations of general relativity are non-linear, a lump of energy made out of pure gravitational fields, like a black hole, would move on a trajectory which is determined by the Einstein field equations themselves, not by a new law. So Einstein proposed that the path of a singular solution, like a black hole, would be determined to be a geodesic from general relativity itself.

This was established by Einstein, Infeld, and Hoffmann for pointlike objects without angular momentum, and by Roy Kerr for spinning objects.

Old quantum theory

Photons and energy quanta

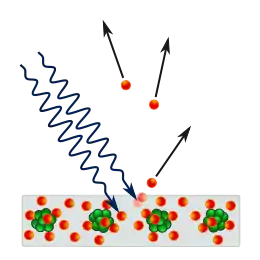

In a 1905 paper,[187] Einstein postulated that light itself consists of localized particles (quanta). Einstein's light quanta were nearly universally rejected by all physicists, including Max Planck and Niels Bohr. This idea only became universally accepted in 1919, with Robert Millikan's detailed experiments on the photoelectric effect, and with the measurement of Compton scattering.

Einstein concluded that each wave of frequency f is associated with a collection of photons with energy hf each, where h is Planck's constant. He does not say much more, because he is not sure how the particles are related to the wave. But he does suggest that this idea would explain certain experimental results, notably the photoelectric effect.[187]

Quantized atomic vibrations

In 1907, Einstein proposed a model of matter where each atom in a lattice structure is an independent harmonic oscillator. In the Einstein model, each atom oscillates independently—a series of equally spaced quantized states for each oscillator. Einstein was aware that getting the frequency of the actual oscillations would be difficult, but he nevertheless proposed this theory because it was a particularly clear demonstration that quantum mechanics could solve the specific heat problem in classical mechanics. Peter Debye refined this model.[234]

Adiabatic principle and action-angle variables

Throughout the 1910s, quantum mechanics expanded in scope to cover many different systems. After Ernest Rutherford discovered the nucleus and proposed that electrons orbit like planets, Niels Bohr was able to show that the same quantum mechanical postulates introduced by Planck and developed by Einstein would explain the discrete motion of electrons in atoms, and the periodic table of the elements.

Einstein contributed to these developments by linking them with the 1898 arguments Wilhelm Wien had made. Wien had shown that the hypothesis of adiabatic invariance of a thermal equilibrium state allows all the blackbody curves at different temperature to be derived from one another by a simple shifting process. Einstein noted in 1911 that the same adiabatic principle shows that the quantity which is quantized in any mechanical motion must be an adiabatic invariant. Arnold Sommerfeld identified this adiabatic invariant as the action variable of classical mechanics.

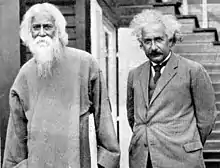

Bose–Einstein statistics

In 1924, Einstein received a description of a statistical model from Indian physicist Satyendra Nath Bose, based on a counting method that assumed that light could be understood as a gas of indistinguishable particles. Einstein noted that Bose's statistics applied to some atoms as well as to the proposed light particles, and submitted his translation of Bose's paper to the Zeitschrift für Physik. Einstein also published his own articles describing the model and its implications, among them the Bose–Einstein condensate phenomenon that some particulates should appear at very low temperatures.[235] It was not until 1995 that the first such condensate was produced experimentally by Eric Allin Cornell and Carl Wieman using ultra-cooling equipment built at the NIST–JILA laboratory at the University of Colorado at Boulder.[236] Bose–Einstein statistics are now used to describe the behaviors of any assembly of bosons. Einstein's sketches for this project may be seen in the Einstein Archive in the library of the Leiden University.[185]

Wave–particle duality

Although the patent office promoted Einstein to Technical Examiner Second Class in 1906, he had not given up on academia. In 1908, he became a Privatdozent at the University of Bern.[237] In "Über die Entwicklung unserer Anschauungen über das Wesen und die Konstitution der Strahlung" ("The Development of our Views on the Composition and Essence of Radiation"), on the quantization of light, and in an earlier 1909 paper, Einstein showed that Max Planck's energy quanta must have well-defined momenta and act in some respects as independent, point-like particles. This paper introduced the photon concept (although the name photon was introduced later by Gilbert N. Lewis in 1926) and inspired the notion of wave–particle duality in quantum mechanics. Einstein saw this wave–particle duality in radiation as concrete evidence for his conviction that physics needed a new, unified foundation.

Zero-point energy

In a series of works completed from 1911 to 1913, Planck reformulated his 1900 quantum theory and introduced the idea of zero-point energy in his "second quantum theory". Soon, this idea attracted the attention of Einstein and his assistant Otto Stern. Assuming the energy of rotating diatomic molecules contains zero-point energy, they then compared the theoretical specific heat of hydrogen gas with the experimental data. The numbers matched nicely. However, after publishing the findings, they promptly withdrew their support, because they no longer had confidence in the correctness of the idea of zero-point energy.[238]

Stimulated emission

In 1917, at the height of his work on relativity, Einstein published an article in Physikalische Zeitschrift that proposed the possibility of stimulated emission, the physical process that makes possible the maser and the laser.[239] This article showed that the statistics of absorption and emission of light would only be consistent with Planck's distribution law if the emission of light into a mode with n photons would be enhanced statistically compared to the emission of light into an empty mode. This paper was enormously influential in the later development of quantum mechanics, because it was the first paper to show that the statistics of atomic transitions had simple laws.

Matter waves

Einstein discovered Louis de Broglie's work and supported his ideas, which were received skeptically at first. In another major paper from this era, Einstein gave a wave equation for de Broglie waves, which Einstein suggested was the Hamilton–Jacobi equation of mechanics. This paper would inspire Schrödinger's work of 1926.

Einstein's objections to quantum mechanics

Einstein played a major role in developing quantum theory, beginning with his 1905 paper on the photoelectric effect. However, he became displeased with modern quantum mechanics as it had evolved after 1925, despite its acceptance by other physicists. He was skeptical that the randomness of quantum mechanics was fundamental rather than the result of determinism, stating that God "is not playing at dice".[240] Until the end of his life, he continued to maintain that quantum mechanics was incomplete.[241]

Bohr versus Einstein

The Bohr–Einstein debates were a series of public disputes about quantum mechanics between Einstein and Niels Bohr, who were two of its founders. Their debates are remembered because of their importance to the philosophy of science.[242][243][244] Their debates would influence later interpretations of quantum mechanics.

Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen paradox

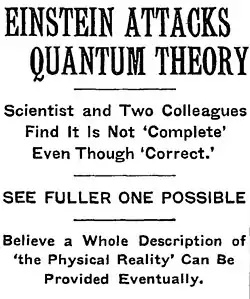

In 1935, Einstein returned to quantum mechanics, in particular to the question of its completeness, in the "EPR paper".[244] In a thought experiment, he considered two particles which had interacted such that their properties were strongly correlated. No matter how far the two particles were separated, a precise position measurement on one particle would result in equally precise knowledge of the position of the other particle; likewise a precise momentum measurement of one particle would result in equally precise knowledge of the momentum of the other particle, without needing to disturb the other particle in any way.[245]

Given Einstein's concept of local realism, there were two possibilities: (1) either the other particle had these properties already determined, or (2) the process of measuring the first particle instantaneously affected the reality of the position and momentum of the second particle. Einstein rejected this second possibility (popularly called "spooky action at a distance").[245]

Einstein's belief in local realism led him to assert that, while the correctness of quantum mechanics was not in question, it must be incomplete. But as a physical principle, local realism was shown to be incorrect when the Aspect experiment of 1982 confirmed Bell's theorem, which J. S. Bell had delineated in 1964. The results of these and subsequent experiments demonstrate that quantum physics cannot be represented by any version of the picture of physics in which "particles are regarded as unconnected independent classical-like entities, each one being unable to communicate with the other after they have separated."[246]

Although Einstein was wrong about local realism, his clear prediction of the unusual properties of its opposite, entangled quantum states, has resulted in the EPR paper becoming among the top ten papers published in Physical Review. It is considered a centerpiece of the development of quantum information theory.[247]

Unified field theory

Following his research on general relativity, Einstein entered into a series of attempts to generalize his geometric theory of gravitation to include electromagnetism as another aspect of a single entity. In 1950, he described his "unified field theory" in a Scientific American article titled "On the Generalized Theory of Gravitation".[248] Although he continued to be lauded for his work, Einstein became increasingly isolated in his research, and his efforts were ultimately unsuccessful. In his pursuit of a unification of the fundamental forces, Einstein ignored some mainstream developments in physics, most notably the strong and weak nuclear forces, which were not well understood until many years after his death. Mainstream physics, in turn, largely ignored Einstein's approaches to unification. Einstein's dream of unifying other laws of physics with gravity motivates modern quests for a theory of everything and in particular string theory, where geometrical fields emerge in a unified quantum-mechanical setting.

Other investigations

Einstein conducted other investigations that were unsuccessful and abandoned. These pertain to force, superconductivity, and other research.

Collaboration with other scientists

In addition to longtime collaborators Leopold Infeld, Nathan Rosen, Peter Bergmann and others, Einstein also had some one-shot collaborations with various scientists.

Einstein–de Haas experiment

Einstein and De Haas demonstrated that magnetization is due to the motion of electrons, nowadays known to be the spin. In order to show this, they reversed the magnetization in an iron bar suspended on a torsion pendulum. They confirmed that this leads the bar to rotate, because the electron's angular momentum changes as the magnetization changes. This experiment needed to be sensitive because the angular momentum associated with electrons is small, but it definitively established that electron motion of some kind is responsible for magnetization.

Schrödinger gas model

Einstein suggested to Erwin Schrödinger that he might be able to reproduce the statistics of a Bose–Einstein gas by considering a box. Then to each possible quantum motion of a particle in a box associate an independent harmonic oscillator. Quantizing these oscillators, each level will have an integer occupation number, which will be the number of particles in it.

This formulation is a form of second quantization, but it predates modern quantum mechanics. Erwin Schrödinger applied this to derive the thermodynamic properties of a semiclassical ideal gas. Schrödinger urged Einstein to add his name as co-author, although Einstein declined the invitation.[249]

Einstein refrigerator

In 1926, Einstein and his former student Leó Szilárd co-invented (and in 1930, patented) the Einstein refrigerator. This absorption refrigerator was then revolutionary for having no moving parts and using only heat as an input.[250] On 11 November 1930, U.S. Patent 1,781,541 was awarded to Einstein and Leó Szilárd for the refrigerator. Their invention was not immediately put into commercial production, and the most promising of their patents were acquired by the Swedish company Electrolux.[note 6]

Non-scientific legacy

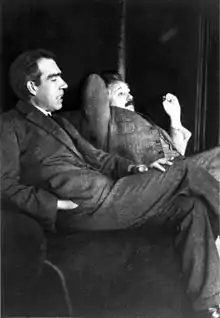

.jpg.webp)

Credit: University of Oslo

While traveling, Einstein wrote daily to his wife Elsa and adopted stepdaughters Margot and Ilse. The letters were included in the papers bequeathed to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Margot Einstein permitted the personal letters to be made available to the public, but requested that it not be done until twenty years after her death (she died in 1986[252]). Einstein had expressed his interest in the plumbing profession and was made an honorary member of the Plumbers and Steamfitters Union.[253][254] Barbara Wolff, of the Hebrew University's Albert Einstein Archives, told the BBC that there are about 3,500 pages of private correspondence written between 1912 and 1955.[255]

Corbis, successor to The Roger Richman Agency, licenses the use of his name and associated imagery, as agent for the university.[256]

The Einstein rights were litigated in 2015 in a federal district court in California. Although the court initially held that the Einstein rights had expired,[257] that ruling was immediately appealed, and the decision was later vacated in its entirety. The court's initial decision no longer has any legal impact or effect of any kind. The underlying claims between the parties in that lawsuit were ultimately settled. The Einstein rights are enforceable, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem is the exclusive representative of those rights.[258]

In popular culture

In the period before World War II, The New Yorker published a vignette in their "The Talk of the Town" feature saying that Einstein was so well known in America that he would be stopped on the street by people wanting him to explain "that theory". He finally figured out a way to handle the incessant inquiries. He told his inquirers "Pardon me, sorry! Always I am mistaken for Professor Einstein."[259]

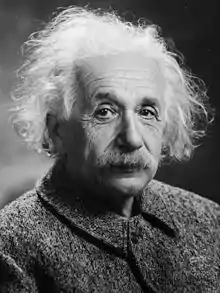

Einstein has been the subject of or inspiration for many novels, films, plays, and works of music.[260] He is a favorite model for depictions of absent-minded professors; his expressive face and distinctive hairstyle have been widely copied and exaggerated. Time magazine's Frederic Golden wrote that Einstein was "a cartoonist's dream come true".[261]

Many popular quotations are often misattributed to him.[262][263]

Awards and honors

Einstein received numerous awards and honors, and in 1922, he was awarded the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect". None of the nominations in 1921 met the criteria set by Alfred Nobel, so the 1921 prize was carried forward and awarded to Einstein in 1922.[10]

Publications

Scientific

- Einstein, Albert (1901) [Manuscript received: 16 December 1900]. Written at Zurich, Switzerland. "Folgerungen aus den Capillaritätserscheinungen" [Conclusions Drawn from the Phenomena of Capillarity]. Annalen der Physik (in German). Hoboken, New Jersey (published 14 March 2006). 309 (3): 513–523. Bibcode:1901AnP...309..513E. doi:10.1002/andp.19013090306.

- Einstein, Albert (1905a) [Manuscript received: 18 March 1905]. Written at Berne, Switzerland. "Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt" [On a Heuristic Viewpoint Concerning the Production and Transformation of Light] (PDF). Annalen der Physik (in German). Hoboken, New Jersey (published 10 March 2006). 322 (6): 132–148. Bibcode:1905AnP...322..132E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053220607.

- Einstein, Albert (1905b) [Completed 30 April and submitted 20 July 1905]. Written at Berne, Switzerland, published by Wyss Buchdruckerei. Eine neue Bestimmung der Moleküldimensionen [A new determination of molecular dimensions] (PDF). Dissertationen Universität Zürich (PhD Thesis) (in German). Zurich, Switzerland: ETH Zürich (published 2008). doi:10.3929/ethz-a-000565688 – via ETH Bibliothek.

- Einstein, Albert (1905c) [Manuscript received: 11 May 1905]. Written at Berne, Switzerland. "Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen" [On the Motion – Required by the Molecular Kinetic Theory of Heat – of Small Particles Suspended in a Stationary Liquid]. Annalen der Physik (in German). Hoboken, New Jersey (published 10 March 2006). 322 (8): 549–560. Bibcode:1905AnP...322..549E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053220806. hdl:10915/2785.

- Einstein, Albert (1905d) [Manuscript received: 30 June 1905]. Written at Berne, Switzerland. "Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper" [On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies]. Annalen der Physik (Submitted manuscript) (in German). Hoboken, New Jersey (published 10 March 2006). 322 (10): 891–921. Bibcode:1905AnP...322..891E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053221004. hdl:10915/2786.

- Einstein, Albert (1905e) [Manuscript received: 27 September 1905]. Written at Berne, Switzerland. "Ist die Trägheit eines Körpers von seinem Energieinhalt abhängig?" [Does the Inertia of a Body Depend Upon Its Energy Content?]. Annalen der Physik (in German). Hoboken, New Jersey (published 10 March 2006). 323 (13): 639–641. Bibcode:1905AnP...323..639E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053231314.

- Einstein, Albert (1915) [Published 25 November 1915]. "Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation" [The Field Equations of Gravitation] (Online page images). Sitzungsberichte 1915 (in German). Berlin, Germany: Königlich Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften: 844–847 – via ECHO, Cultural Heritage Online, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science.

- Einstein, Albert (22 June 1916). "Näherungsweise Integration der Feldgleichungen der Gravitation" [Approximate integration of the field equations of gravitation]. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Berlin: 688–696. Bibcode:1916SPAW.......688E. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- Einstein, Albert (1917a). "Kosmologische Betrachtungen zur allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie" [Cosmological Considerations in the General Theory of Relativity]. Sitzungsberichte 1917 (in German). Königlich Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin.

- Einstein, Albert (1917b). "Zur Quantentheorie der Strahlung" [On the Quantum Mechanics of Radiation]. Physikalische Zeitschrift (in German). 18: 121–128. Bibcode:1917PhyZ...18..121E.

- Einstein, Albert (31 January 1918). "Über Gravitationswellen" [About gravitational waves]. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Berlin: 154–167. Bibcode:1918SPAW.......154E. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- Einstein, Albert (1923) [First published 1923, in English 1967]. Written at Gothenburg. Grundgedanken und Probleme der Relativitätstheorie [Fundamental Ideas and Problems of the Theory of Relativity] (Speech). Lecture delivered to the Nordic Assembly of Naturalists at Gothenburg, 11 July 1923. Nobel Lectures, Physics 1901–1921 (in German and English). Stockholm: Nobelprice.org (published 3 February 2015) – via Nobel Media AB 2014.

- Einstein, Albert (1924) [Published 10 July 1924]. "Quantentheorie des einatomigen idealen Gases" [Quantum theory of monatomic ideal gases]. Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Physikalisch-Mathematische Klasse (in German): 261–267. Archived from the original (Online page images) on 14 October 2016 – via ECHO, Cultural Heritage Online, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. First of a series of papers on this topic.