Scottish Agricultural Revolution

The Agricultural Revolution in Scotland was a series of changes in agricultural practice that began in the seventeenth century and continued in the nineteenth century. They began with the improvement of Scottish Lowlands farmland and the beginning of a transformation of Scottish agriculture from one of the least modernised systems to what was to become the most modern and productive system in Europe. The traditional system of agriculture in Scotland generally used the runrig system of management, which had possibly originated in the late medieval period. The basic pre-improvement farming unit was the baile (in the Highlands) and the fermetoun (in the Lowlands). In each, a small number of families worked open-field arable and shared grazing. Whilst run rig varied in its detail from place to place, the common defining detail was the sharing out by lot on a regular (probably annual) basis of individual parts ("rigs") of the arable land so that families had intermixed plots in different parts of the field.[1]:149[2](p24)

Use of the term

The term Scottish Agricultural Revolution was used in the early twentieth century primarily to refer to the period of most dramatic change in the second half of the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century. More recently historians have become aware of a longer processes, with change beginning in the late seventeenth century and still continuing into the mid-nineteenth century. The expansion of the period covered has led some to question the concept of a revolution.[3]

History

Seventeenth century

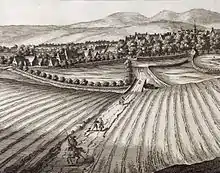

Before the seventeenth century, with difficult terrain, poor roads and methods of transport there was little trade between different areas of the country and most settlements depended on what was produced locally, often with very little in reserve in bad years. Most farming was based on the lowland fermtoun or highland baile, settlements of a handful of families that jointly farmed an area notionally suitable for two or three plough teams, allocated in run rigs, of "runs" (furrows) and "rigs" (ridges), to tenant farmers. Most ploughing was done with a heavy wooden plough with an iron coulter, pulled by oxen, which were more effective in the heavy Scottish soil, and cheaper to feed than horses.[4] Those with property rights included husbandmen, lesser landholders and free tenants.[5] Below them were the cottars, who often shared rights to common pasture, occupied small portions of land and participated in joint farming as hired labour. Farms also might have grassmen, who had rights only to grazing.[5] Three acts of parliament passed in 1695 allowed the consolidation of runrigs and the division of common land.[6]

Eighteenth century

After the union with England in 1707, there was a conscious attempt among the gentry and nobility to improve agriculture in Scotland. The Society of Improvers was founded in 1723, including in its 300 members dukes, earls, lairds and landlords.[7] In the first half of the century these changes were limited to tenanted farms in East Lothian and the estates of a few enthusiasts, such as John Cockburn and Archibald Grant. Not all were successful, with Cockburn driving himself into bankruptcy, but the ethos of improvement spread among the landed classes.[8]

The English plough was introduced along with foreign grasses, the sowing of rye grass and clover. Turnips and cabbages were introduced, lands enclosed and marshes drained, lime was put down, roads built and woods planted. Drilling and sowing and crop rotation were introduced. The introduction of the potato to Scotland in 1739 greatly improved the diet of the peasantry. Enclosures began to displace the runrig system and free pasture. There was increasing specialisation, with the Lothians became a major centre of grain, Ayrshire of cattle breeding and The Borders of sheep.[7]

Although some estate holders improved the quality of life of their displaced workers,[7] the Agricultural Revolution led directly to what is increasingly becoming known as the Lowland Clearances,[9] with hundreds of thousands of cottars and tenant farmers from central and southern Scotland emigrating from the farms and small holdings their families had occupied for hundreds of years, or adapting them to the Scottish Agricultural Revolution.[7]

Nineteenth century

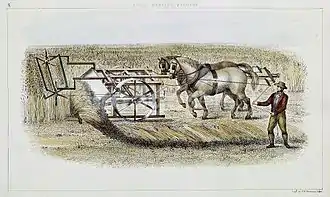

Improvement continued in the nineteenth century. Innovations included the first working reaping machine, developed by Patrick Bell in 1828. His rival James Smith turned to improving sub-soil drainage and developed a method of ploughing that could break up the subsoil barrier without disturbing the topsoil. Previously unworkable low-lying carselands could now be brought into arable production and the result was the even Lowland landscape that still predominates.[10]

While the Lowlands had seen widespread agricultural improvement, the financially broken Highland lairds took to replacing Highland agricultural practice with its own system of labour with Lowland agricultural practice plus labour in the Highland Clearances.[11] A handful of powerful families, typified by the dukes of Argyll, Atholl, Buccleuch, and Sutherland, owned enormous sections of Scotland and had extensive influence on political affairs (certainly up to 1885). As late as 1878, 68 families owned nearly half the land in Scotland.[12] Particularly after the end of the boom created by the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1790–1815), these landlords needed cash to maintain their position in London society. They turned to money rents and downplayed the traditional patriarchal relationship that had historically sustained the clans.

One result of these changes were the Highland Clearances, in which many tenants in the Highlands were evicted as lands were enclosed, principally so that they could be used for sheep farming. The clearances followed patterns of agricultural change throughout the UK, though were notorious as a result of the introduction of Lowland farmhands or practice into Highland agricultural land or practice, plus the lack of legal protection for year-by-year tenants under Scots law, and the abruptness of the change from the traditional clan system.[13] The result was a continuous exodus from the land—to the cities, or further afield to England, Canada, America or Australia.[14]

Consequences

The Lowland and Highland Clearances meant that many small settlements were dismantled, their occupants forced either to the new purpose-built villages built by the landowners such as John Cockburn's Ormiston or Archibald Grant's Monymusk[15] on the outskirts of the new ranch-style farms, or to the new industrial centres of Glasgow, Edinburgh, or northern England. Tens of thousands of others emigrated to Canada or the United States, finding opportunities there to own and farm their own land.[7] In the Highlands many that remained were now crofters, living on very small rented farms with indefinite tenure used to raise various crops and animals. For these families kelping, fishing, spinning of linen and military service became important sources of additional revenue.[16]

Notes

- Dodgshon, Robert A. (1998). From Chiefs to Landlords: Social and Economic Change in the Western Highlands and Islands, c.1493-1820. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0 7486 1034 0.

- Devine, T M (2018). The Scottish Clearances: A History of the Dispossessed, 1600-1900. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0241304105.

- I. D. Whyte and K. A. Whyte, The Changing Scottish Landscape: 1500–1800 (London: Taylor & Francis, 1991), ISBN 0415029929, p. 126.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 41–55.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, p. 82.

- K. Bowie, "New perspectives on pre-union Scotland" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0191624330, p. 314.

- J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 288–91. Gilles Denis, "Sociétés d'agriculture et diffusion des Lumières" in Frank Salaün and Jean-Pierre Schandeler, Enquête sur le Construction des Lumières (Centre international d'étude du XVIIIe siècle: Ferney-Voltaire, 2018), pp. 108-109.

- I. D. Whyte, "Economy: primary sector: 1 Agriculture to 1770s", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 206–7.

- Robert Allan Houston and Ian D. Whyte, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-89167-1, pp. 148–151.

- G. Sprot, "Agriculture, 1770s onwards", in M. Lynch, ed., Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), ISBN 0199693056, pp. 321–3.

- M. Gray, The Highland Economy, 1750–1850 (London: Greenwood, 1976), ISBN 0-8371-8536-X.

- H. Pelling, Social Geography of British Elections 1885–1910 (1960, Gregg Revivals, rpt., 1994), ISBN 0-7512-0278-9, p. 373.

- E. Richards, The Highland Clearances: People, Landlords and Rural Turmoil (Edinburgh, Birlinn Press, 2008), ISBN 1-84158-542-4.

- J. Wormald, Scotland: a History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-19-820615-1, p. 229.

- D. Ross, Scotland: History of a Nation (Lomond Books, 2000), ISBN 0947782583, p. 229.

- M. J. Daunton, Progress and Poverty: An Economic and Social History of Britain 1700–1850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), ISBN 0-19-822281-5, p. 85.

Further reading

- Devine, Thomas Martin, The Transformation of Rural Scotland: Social Change and the Agrarian Economy, 1660–1815 (Edinburgh University Press, 1994).