2001 United Kingdom foot-and-mouth outbreak

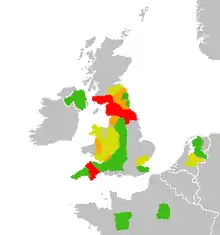

The outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in the United Kingdom in 2001 caused a crisis in British agriculture and tourism. This epizootic saw 2,000 cases of the disease in farms across most of the British countryside. Over 6 million cows and sheep were killed in an eventually successful attempt to halt the disease.[1] Cumbria was the worst affected area of the country, with 893 cases.

With the intention of controlling the spread of the disease, public rights of way across land were closed by order. This damaged the popularity of the Lake District as a tourist destination and led to the cancellation of that year's Cheltenham Festival, as well as the British Rally Championship for the 2001 season and delaying that year's general election by a month. By the time that the disease was halted in October 2001, the crisis was estimated to have cost the United Kingdom £8bn.

Background

Britain's last outbreak had been in 1967, and had been confined to a small area of the country. The Northumberland report issued after the 1967 outbreak had identified that speed was the key to stopping a future outbreak. When identified, animals should be slaughtered on the spot that same day, and the carcasses buried in quicklime.

In 1980, foot and mouth treatment policy passed from the hands of the UK Government to the European level as a result of European Community (EC) directive, 85/511. This set out procedures, such as protection and "surveillance zones", the confirmation of diagnosis by laboratory testing and that actions had to be consulted with the EC and its Standing Veterinary Committee. An earlier directive, 80/68, on the protection of groundwater gave powers to the Environment Agency to prohibit farm burials and the use of quicklime unless the site was authorised by the Agency.

Since the 1967 outbreak, there had also been significant changes in farming methods. The closure of many local abattoirs meant that animals for slaughter were now being transported greater distances.

Start of crisis

.JPG.webp)

The first case of the disease to be detected was at Cheale Meats abattoir in Little Warley, Essex on 19 February 2001 on pigs from Buckinghamshire and the Isle of Wight. Over the next four days, several more cases were announced in Essex. On 23 February, a case was confirmed in Heddon-on-the-Wall, Northumberland, from where the pig in the first case had come; this farm was later confirmed as the source of the outbreak and the owner, Bobby Waugh of Pallion, was found guilty of having failed to inform the authorities of a notifiable disease and banned from keeping farm animals for 15 years. He was later found guilty of feeding his pigs "untreated waste".[2][3][4]

On 24 February, a case was announced in Highampton in Devon. Later in the week, North Wales was affected. By the beginning of March, the disease had spread to Cornwall, southern Scotland and the Lake District where it took a particularly strong hold.

During investigation of the Great Heck rail crash, which took place on 28 February in North Yorkshire, investigators visiting the crash site had to go through a decontamination regimen, to prevent possible contamination of the crash site's soil with the virus.[5]

The policy of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) was that where the carcasses from the cull could not be disposed on site, they would have to be taken to a rendering plant in Widnes; as such the corpses of infected animals were taken through disease-free areas. By 16 March, the number of cases was at 240. MAFF adopted a policy of "contiguous cull" – all animals within three kilometres (2 miles) of known cases would be slaughtered. This was immediately clarified as applying only to sheep, not cows or pigs.

Around this time, the Netherlands had a small outbreak, the disease was contained by vaccination; the vaccinated animals would later be destroyed, in line with EU requirements on trading.

Two men were appointed to approach policy in a scientific manner: the Chief Scientist Professor David King, and Professor Roy Anderson, an epidemiologist who had been modelling human diseases at Imperial College and was on the committee concerned with BSE.

By the end of March the disease was at its height, with up to 50 new cases a day.

In April, King announced that the disease was "totally under control".[6]

The effort to prevent the spread of the disease, which caused a complete ban of the sale of British pigs, sheep and cattle until the disease was confirmed eradicated, concentrated on a cull and then by burning all animals located near an infected farm. The complete halt on movement of livestock, cull, and extensive measures to prevent humans carrying the disease on their boots and clothing from one site to another, brought the disease under control during the summer. From May to September, about five cases per day were reported.

The culling required resources that were not immediately to hand. With about 80,000–93,000 animals per week being slaughtered, MAFF officials were assisted by units from the British Army commanded by Brigadier Alex Birtwistle.

End of outbreak

The final case was reported on Whygill Head Farm near Appleby in Cumbria on 30 September. The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) downgraded to "high risk" the last area to be denoted "infected" on 29 November. The last cull in the UK was performed on 1 January 2002 on 2,000 sheep at Donkley Woods Farm, Bellingham, Northumberland. Restrictions on livestock movement were retained into 2002.

The use of a vaccine to halt the spread of the disease was repeatedly considered during the outbreak, but the government never decided to use it after pressure from the National Farmers Union. Although the vaccine was believed to be effective, export rules would prevent the export of British livestock in the future, and it was decided that this was too great a price to pay, although this was controversial because the value of the export industry (£592 million per year; MAFF figures reported by the Guardian[7]) was small compared to losses to tourism resulting from the measures taken. Following the outbreak, the law was changed to allow vaccinations rather than culling.

The consensus today is that the FMD virus came from infected or contaminated meat that was part of the swill being fed to pigs at Burnside Farm in Heddon-on-the-Wall.[8] The swill had not been properly heat-sterilized and the virus had thus been allowed to infect the pigs.

Seeing as FMD virus was apparently not present in the UK beforehand, and given the import restrictions for meat from countries known to harbour FMD, it is likely that the infected meat had been illegally imported to the UK. Such imports are likely to be for the catering industry and a total ban on the feeding of catering waste containing meat or meat products was introduced early in the epidemic.[8]

Spread to the rest of Europe

Several cases of foot and mouth were reported in Ireland and mainland Europe, following unknowing transportation of infected animals from the UK. The cases sparked fears of a continent-wide pandemic, but these proved unfounded.

The Netherlands was the worst affected country outside the UK, suffering 25 cases. Vaccinations were used to halt the spread of the disease. However, the Dutch went on to slaughter all vaccinated animals and in the end 250,000–270,000 cattle were destroyed, resulting in significantly more cattle slaughtered per infected premises than in the UK.[9]

Ireland suffered one case in a flock of sheep in Jenkinstown in County Louth in March 2001. A cull of healthy livestock around the farm was ordered. Irish special forces sniped wild animals capable of bearing the disease, such as deer, in the area. The outbreak greatly affected the Irish food and tourism industry. The 2001 Saint Patrick's Day festival was cancelled, but later rescheduled two months later in May. Severe precautionary measures had been in place throughout Ireland since the outbreak of the disease in the UK, with most public events and gatherings cancelled, controls on farm access, and measures such as disinfectant mats at railway stations, public buildings and university campuses. The 2001 Oireachtas Rince na Cruinne, or Irish Dance World Championships, was cancelled this year due to these measures. Causeway 2001, an Irish Scouting Jamboree was also cancelled. Three matches involving Ireland in rugby union's 2001 Six Nations Championship were postponed until the autumn.

France suffered two cases, on 13 March and 23 March.

Belgium, Spain, Luxembourg and Germany carried out some precautionary slaughters, but all tests eventually proved negative. Further false alarms that did not result in any culling were signalled in Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Italy. All other European countries imposed livestock movement restrictions from infected or potentially infected countries.

The outbreak caused the delay by a month of the local elections. Part of the reason was that bringing together so many farmers at polling stations might cause extensive spread of the disease. However, more importantly, it was widely known before the outbreak that the Government had chosen the day of the local elections to hold the general election. Holding a general election during the height of the crisis was widely seen as impossible – Government work is much reduced during the four-week campaign and it was seen as inappropriate to divert attention away from management of the crisis. The announcement was leaked to newspapers at the end of March. Prime Minister Tony Blair confirmed the decision on 2 April. Opposition leader William Hague concurred with the reasons for delay, and even suggested a further delay to ensure that the crisis was truly over (though it was alleged that he was hoping the Tories would be more popular and do better at the coming election the later it took place, perhaps because of bad government handling of the foot and mouth situation).[10] The general election was eventually held on 7 June, along with the local elections. It was the first delay of an election since the Second World War.

Following the election, Blair announced a re-organisation of the government departments. Largely in response to the perceived failure of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food to respond to the outbreak quickly and effectively enough, the ministry was merged with elements of the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions to form the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA).

Reports

.JPG.webp)

As the 2001 outbreak seemed to cause as much harm as the previous outbreak in 1967, there was a widespread government and public perception that little had been learnt from the previous epizootic (despite the publication in 1968 of a report, the Northumberland Inquiry, on the previous outbreak). In August 2001 therefore, in an effort to prevent this failure to learn from history from happening again, HM Government launched three inquiries into various aspects of the crisis. They were:

- Inquiry into the lessons to be learned from the foot and mouth disease outbreak of 2001. This inquiry was devoted specifically to the government's handling of the crisis. It was chaired by Sir Iain Anderson CBE, previously a special adviser to Tony Blair, and reported in July 2002.

- The Royal Society Inquiry into Infectious Diseases in Livestock. This inquiry examined the scientific aspects of the crisis, for instance the efficacy of vaccinations, the way the virus spreads and so on. It was chaired by Sir Brian Follett and also reported in July 2002.

- Policy Commission on the Future of Farming and Food. This inquiry focused on the long-term production and delivery of food within the country. It was chaired by Sir Donald Curry and reported in January 2002.

All three inquiries reported their findings to the public. However, the inquiries themselves took place in private. The lack of a full public inquiry into the crisis caused a group of farmers, business leaders and media organisations to lodge an appeal at the High Court against the government's decision not to hold such an inquiry. Margaret Beckett, Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, had ruled out a public inquiry on the grounds that it would be too costly and take too long. After a four-day hearing, the court sided with Beckett and the Government.

An Independent Inquiry into Foot and Mouth Disease in Scotland initiated by the Royal Society of Edinburgh was chaired by Professor Ian Cunningham. This embraced not only the scientific aspects of the outbreak, but also economic, social and psychological effects of the event. The costs to Scottish agriculture of the FMD outbreak were estimated to be £231m and the loss of gross revenue to tourism to be between £200–250m for Scotland as a whole. It recommended that there should be a regional laboratory in Scotland, and priority be given to the development of testing procedures. The delay in imposing a ban of all movements until the third day after confirmation, the use of less than transparent modelling techniques and the failure to call on more than a fraction of the considerable relevant scientific expertise available in Scotland were criticised. The case for emergency protective vaccination, without subsequent slaughter, was supported by the evidence and it was recommended that contingency plans should include emergency barrier, or ring, vaccination as an adjunct to slaughter in clinical cases. Reservations about the consumption of meat and milk from vaccinated animals were seen to be unjustified. The importance of biosecurity at all times and throughout the agricultural industry was emphasised and it stated that SEERAD (The Scottish Executive Environment and Rural Affairs Department) should take the lead in establishing standards to be applied in normal times and at the start of an outbreak. A Chief Veterinary Officer (Scotland) should be appointed and a "Territorial Veterinary Army" formed from professionals to be called upon should need arise. Burial of carcasses, where conditions permit, was identified as the preferred option for disposal of slaughtered animals. The Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) should have a clear role in contingency planning and management of any future emergency. There was a need for operational guidelines for slaughtermen. In formulating movement restriction, the dispersed nature of many holdings should be taken into account. There should be a clear and consistent strategy for compensation for slaughtered animals. The closing down of the country initially for no more than three weeks and then reopening in non-affected areas was recommended. Great importance was placed on contingency planning, on the need for regular exercises and on the setting up of an independent standing committee to monitor the maintenance of effective planning. In all, some twenty seven recommendations were made to the Scottish Executive.

The Farm Animal Welfare Council, an independent advisory body established by the Government in 1979, also published a report. Its recommendations including material from both The Royal Society Inquiry into Infectious Diseases in Livestock and the Independent Inquiry into Foot and Mouth Disease in Scotland.

Health and social consequences

The Department of Health (DH) sponsored a longitudinal research project investigating the health and social consequences of the 2001 outbreak of FMD. The research team was led by Dr Maggie Mort of Lancaster University and fieldwork took place between 2001 and 2003.[11] Concentrating on Cumbria as the area that was worst hit by the epidemic, data has been collected via interviews, focus groups and individual diaries in order to document the consequences that the FMD outbreak had on people's lives. In 2008, a book based on this study was published, titled Animal Disease and Human Trauma, emotional geographies of disaster.[12]

Under the EU systems, compensation could be paid to farmers, but only those whose animals were slaughtered; those who suffered as a result of movement restrictions, albeit due to government action, could not be compensated.

Later reaction

In the light of the reports' extensive recommendations, in June 2004, DEFRA held a simulation exercise in five areas around the country to test new procedures to be employed in the event of a future outbreak. Unlike the outbreak in the 1960s, the main reason that MAFF failed to respond quickly enough was the high level of cattle movement in the modern-day market: by the 21st century, cattle were being moved quickly up and down the country without tests for disease. However, the government was accused by the NFU of acting too slowly in the early stages of the outbreak, and the Agriculture Minister attempted at least as late as 11 March to claim incorrectly that the outbreak was under control.[13]

References

- Knight-Jones, T. J.; Rushton, J (2013). "The economic impacts of foot and mouth disease – What are they, how big are they and where do they occur?". Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 112 (3–4): 161–173. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.07.013. PMC 3989032. PMID 23958457.

- Morris, Doug (30 May 2002). "A farmer's negligence". BBC News. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Abrams, Fran (31 May 2002). "They just wanted a scapegoat". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Wilson, Jamie (29 June 2002). "Foot and mouth farmer banned for 15 years". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- The track obstruction by a road vehicle and subsequent train collisions at Great Heck 28 February 2001 (Report). Health and Safety Executive. February 2002. p. 33. ISBN 0-7176-2163-4.

- based on Not the foot and mouth report: everything Tony Blair did not want you to know about the biggest blunder in his premiership, Private Eye special report November 2001 Archived 18 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Freedland, Jonathan (16 May 2001). "A catalogue of failures that discredits the whole system". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- "Origin of the UK Foot and Mouth Disease Epidemic 2001" (PDF). Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. June 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Royal Society of Edinburgh, Inquiry into foot and mouth disease July 2002

- "DISEASE DAMAGE". pbs.org. PBS. 30 March 2001. Retrieved 24 January 2008.)

- Mort, Maggie; Ian, Convery; Cathy, Bailey; Josephine, Baxter (2004). "The Health and Social Consequences of the 2001 Foot & Mouth Disease Epidemic in North Cumbria" (PDF). Institute for Health Research, Lancaster University. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Convery, Ian; Mort, Maggie; Baxter, Josephine; Bailey, Cathy (2008). Animal disease and human trauma : emotional geographies of disaster. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230227613.

- "Foot-and-mouth crisis timetable". CNN. 7 August 2001.

External links

- Special report on the crisis from BBC News

- European Commission for the control of foot and mouth disease homepage

- Private Eye's "Not the Foot and Mouth report"

- Inquiry into Foot and Mouth Disease in Scotland. The Royal Society of Edinburgh, July 2002

- Farm Animal Welfare Council Report

- Foot and Mouth Disease Study Project website

- Animal Disease and Human Trauma: emotional geographies of disaster

- ESDS Qualidata, Health and Social Consequences of the Foot and Mouth Disease Epidemic in North Cumbria, 2001-2003 webpages

- Foot and Mouth Disease Study information, Lancaster University, School of Health and Medicine, Division of Health Research