Scrap

Scrap consists of recyclable materials left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap has monetary value, especially recovered metals, and non-metallic materials are also recovered for recycling.

Processing

Scrap metal originates both in business and residential environments. Typically a "scrapper" will advertise their services to conveniently remove scrap metal for people who don't need it.

Scrap is often taken to a wrecking yard (also known as a scrapyard, junkyard, or breaker's yard), where it is processed for later melting into new products. A wrecking yard, depending on its location, may allow customers to browse their lot and purchase items before they are sent to the smelters, although many scrap yards that deal in large quantities of scrap usually do not, often selling entire units such as engines or machinery by weight with no regard to their functional status. Customers are typically required to supply all of their own tools and labor to extract parts, and some scrapyards may first require waiving liability for personal injury before entering. Many scrapyards also sell bulk metals (stainless steel, etc.) by weight, often at prices substantially below the retail purchasing costs of similar pieces.

A scrap metal shredder is often used to recycle items containing a variety of other materials in combination with steel. Examples are automobiles and white goods such as refrigerators, stoves, clothes washers, etc. These items are labor-intensive to manually sort things like plastic, copper, aluminum, and brass. By shredding into relatively small pieces, the steel can easily be separated out magnetically. The non-ferrous waste stream requires other techniques to sort.

In contrast to wrecking yards, scrapyards typically sell everything by weight, instead of by item. To the scrapyard, the primary value of the scrap is what the smelter will give them for it, rather than the value of whatever shape the metal may be in. An auto wrecker, on the other hand, would price exactly the same scrap based on what the item does, regardless of what it weighs. Typically, if a wrecker cannot sell something above the value of the metal in it, they would then take it to the scrapyard and sell it by weight. Equipment containing parts of various metals can often be purchased at a price below that of either of the metals, due to saving the scrapyard the labor of separating the metals before shipping them to be recycled.

Thieves sometimes sell stolen items to scrapyards. Copper pipes and wiring, bronze monuments and aluminium siding have all been targets of metal theft, with the number of thefts increasing as prices rise.[1] Manhole covers have also been stolen.[2][3][4] In the 1970s, the term "newsjacking" was coined to describe the theft of newspapers for sale to scrap dealers.[5][6]

Resources

.jpg.webp)

Scrap prices may vary markedly over time and in different locations. Prices are often negotiated among buyers and sellers directly or indirectly over the Internet. Prices displayed as the market prices are not the prices that recyclers will see at the scrap yards. Other prices are ranges or older and not updated frequently. Some scrap yards' websites have updated scrap prices.

In the US, scrap prices are reported in a handful of publications, including American Metal Market, based on confirmed sales as well as reference sites such as Scrap Metal Prices and Auctions. Non-US domiciled publications, such as The Steel Index, also report on the US scrap price, which has become increasingly important to global export markets. Scrap yards directories are also used by recyclers to find facilities in the US and Canada, allowing users to get in contact with yards.

With resources online for recyclers to look at for scrapping tips, like web sites, blogs, and search engines, scrapping is often referred to as a hands and labor-intensive job. Taking apart and separating metals is important to making more money on scrap, for tips like using a magnet to determine ferrous and non-ferrous materials, that can help recyclers make more money on their metal recycling. When a magnet sticks to the metal, it will be a ferrous material, like steel or iron. This is usually a less expensive item that is recycled but usually is recycled in larger quantities of thousands of pounds. Non-ferrous metals like copper, aluminum, and brass do not stick to a magnet. Some cheaper grades of stainless steel are magnetic, other grades are not. These items are higher priced commodities for metal recycling and are important to separate when recycling them. The prices of non-ferrous metals also tend to fluctuate more than ferrous metals so it is important for recyclers to pay attention to these sources and the overall markets.

Hazards

Great potential exists in the scrap metal industry for accidents in which a hazardous material present in scrap causes death, injury, or environmental damage. A classic example is radioactivity in scrap; the Goiânia accident and the Mayapuri radiological accident were incidents involving radioactive materials. Toxic materials such as asbestos, and toxic metals such as beryllium, cadmium, and mercury may pose dangers to personnel, as well as contaminating materials intended for metal smelters.

Many specialized tools used in scrapyards are hazardous, such as the alligator shear, which cuts metal using hydraulic force, compactors, and scrap metal shredders.

Benefits of recycling

.jpg.webp)

According to research conducted by the US Environmental Protection Agency, recycling scrap metals can be quite beneficial to the environment. Using recycled scrap metal in place of virgin iron ore can yield:[7]

- 75% savings in energy.

- 90% savings in raw materials used.

- 86% reduction in air pollution.

- 40% reduction in water use.

- 76% reduction in water pollution.

- 97% reduction in mining wastes.

Every ton of new steel made from scrap steel saves:

- 1,115 kg of iron ore.

- 625 kg of coal.

- 53 kg of limestone.

Energy savings from other metals include:

- Aluminium savings of 95% energy.

- Copper savings of 85% energy.

- Lead savings of 65% energy.

- Zinc savings of 60% energy.

Metal recycling industry

The metal recycling industry encompasses a wide range of metals. The more frequently recycled metals are scrap steel, iron (ISS), lead, aluminium, copper, stainless steel and zinc. There are two main categories of metals: ferrous and non-ferrous. Metals which contain iron in them are known as ferrous.

Metals without iron are non-ferrous.

- Common non-ferrous metals are copper, brass, aluminum, zinc, magnesium, tin, nickel, and lead.

- Usable coins can be deposited in banks. Damaged US coins can be redeemed for money via the Mutilated Coin Redemption Program.

Non-ferrous metals also include precious and exotic metals:

- Precious metals are metals with a high market value in any form, such as gold, silver, and platinum group metals.

- Exotic metals contain rare elements such as cobalt, mercury, titanium, tungsten, arsenic, beryllium, bismuth, cerium, cadmium, niobium, indium, gallium, germanium, lithium, selenium, tantalum, tellurium, vanadium, and zirconium. Some types of metals are radioactive. These may be "naturally occurring" or formed by nuclear reactions. Metals that have been exposed to radioactive sources may also become radioactive in settings such as medical environments, research laboratories, and nuclear power plants.

OSHA guidelines should be followed when recycling any type of scrap metal to ensure safety.[8]

Ferrous metal recycling

Ferrous metals are able to be recycled, with steel being one of the most recycled materials in the world.[9] Ferrous metals contain an appreciable percentage of iron and the addition of carbon and other substances creates steel.

Description

In the United States, steel containers, cans, automobiles, appliances, and construction materials contribute the greatest weight of recycled materials. For example, in 2008, more than 97% of structural steel and 106% of automobiles were recycled, comparing the current steel consumption for each industry with the amount of recycled steel being produced (the late 2000s recession and the associated sharp decline in automobile production in the US explains the over-100% calculation).[10] A typical appliance is about 75% steel by weight[11] and automobiles are about 65% steel and iron.[12]

The steel industry has been actively recycling for more than 150 years, in large part because it is economically advantageous to do so. It is cheaper to recycle steel than to mine iron ore and manipulate it through the production process to form new steel. Steel does not lose any of its inherent physical properties during the recycling process, and has drastically reduced energy and material requirements compared with refinement from iron ore. The energy saved by recycling reduces the annual energy consumption of the industry by about 75%, which is enough to power eighteen million homes for one year.[13] According to the International Resource Panel's Metal Stocks in Society report, the per capita stock of steel in use in Australia, Canada, the European Union EU15, Norway, Switzerland, Japan, New Zealand and the US combined is 7,085 kilograms (15,620 lb) (about 860 million people in 2005).

Basic oxygen steelmaking (BOS) uses 25–35% recycled steel to make new steel. BOS steel usually contains lower concentrations of residual elements such as copper, nickel, and molybdenum, and is therefore more malleable than electric arc furnace (EAF) steel, and is often used to make automotive fenders, tin cans, industrial drums, or any product with a large degree of cold working. EAF steelmaking uses almost 100% recycled steel. This steel contains greater concentrations of residual elements that cannot be removed through the application of oxygen and lime. It is used to make structural beams, plates, reinforcing bar, and other products that require little cold working.[14] Downcycling of steel by hard-to-separate impurities such as copper or tin can only be prevented by well-aimed scrap selection or dilution by pure steel.[15] Recycling one metric ton (1,000 kilograms) of steel saves 1.1 metric tons of iron ore, 630 kilograms of coal, and 55 kilograms of limestone.[16]

Types of scrap used in steelmaking

- Heavy melting steel – Industrial or commercial scrap steel greater than 6 mm thick, such as plates, beams, columns, channels; may also include scrap machinery or implements or certain metal stampings

- Old car bodies – Vehicles with or without interiors and their original wheels

- Cast iron – Cast iron bathtubs, machinery, pipe, and engine blocks

- Pressing steel – Domestic scrap metal up to approx. 6 mm (0.24 in) thick. Examples - "White goods" (fridges, washing machines, etc.), roofing iron, water heaters, water tanks, and sheet metal offcuts

- Reinforcing bars or mesh – Used in the construction industry within concrete structures

- Turnings – Remains of drilling or shaping steels. Also known as "borings" or "swarf"

- Manganese steel – Non-magnetic, hardened steel used in the mining industry, cement mixers, rock crushers, and other high-impact and abrasive environments.

- Rails – Rail or tram tracks[17]

Ship breaking

The hulls of ships, with any usable equipment salvaged and removed, can be broken up to provide scrap steel. For a time countries in south Asia carried out most ship breaking, often using manual methods that were hazardous to workers and the environment. International regulations now dictate treatment of old ships as sources of hazardous waste, so ship breaking has returned to ports in more developed countries. In 2013, about 29 million tons of scrap steel was recovered from broken ships. Some of the scrap can be reheated and rolled to make products such as concrete reinforcing bars, or the scrap may be melted to make new steel.

Economic role

United States

The scrap industry was valued at more than $90 billion in 2012, up from $54 billion in 2009 balance of trade, exporting $28 billion in scrap commodities to 160 countries. Since 2010, the industry has added more than 15,000 jobs, and supports 463,000 workers, both directly and indirectly. In addition, it generates more than $10 billion in revenue for federal, state, and local governments.[18] Scrap recycling also helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions and conserves energy and natural resources. For example, scrap recycling diverts 135 million short tons (121,000,000 long tons; 122,000,000 t) of materials away from landfills. Recycled scrap is a raw material feedstock for nearly 60% of steel made in the US, for almost 50% of the copper and copper alloys produced in the US, for more than 75% of the US paper industry's needs, and for 50% of US aluminum. Recycled scrap helps keep air and water cleaner by removing potentially hazardous materials and keeping them out of landfills.[19]

Image gallery

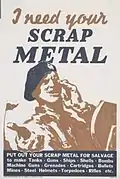

Poster for World War II scrap collection campaign

Poster for World War II scrap collection campaign Scrap depot (Butte, Montana, United States)

Scrap depot (Butte, Montana, United States) This pile of mixed scrap includes an old bus

This pile of mixed scrap includes an old bus Compressed bales consisting mostly of tin cans

Compressed bales consisting mostly of tin cans British Rail locomotives stacked awaiting scrapping

British Rail locomotives stacked awaiting scrapping Flattened cars stacked near Philadelphia (Pennsylvania, United States)

Flattened cars stacked near Philadelphia (Pennsylvania, United States) Scrap car bodies

Scrap car bodies A single compacted car (Finland)

A single compacted car (Finland).jpg.webp) Stacked cubed cars (Calgary, Alberta, Canada)

Stacked cubed cars (Calgary, Alberta, Canada) Compacted scrap pile (Austria)

Compacted scrap pile (Austria).jpg.webp) Rhine River scrap barge (Basel, Switzerland)

Rhine River scrap barge (Basel, Switzerland)

Scrap awaiting export (Bremen, Germany)

Scrap awaiting export (Bremen, Germany) Scrap metal hauler (Libya)

Scrap metal hauler (Libya) Partition made of compacted cars (Birmingham, England)

Partition made of compacted cars (Birmingham, England) A train awaits scrappage (Dublin, Ireland)

A train awaits scrappage (Dublin, Ireland) New York City Subway cars being dumped at sea to enlarge an artificial reef (South Carolina, United States)

New York City Subway cars being dumped at sea to enlarge an artificial reef (South Carolina, United States) Scrap paper dealer (Chandigarh, India)

Scrap paper dealer (Chandigarh, India)

See also

References

- Schwartz, Emma (27 March 2008). "Price Hikes Lead to Rash of Metal Thefts". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "China manhole thefts prove deadly". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 29 January 2004. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Muir, Hugh (25 October 2004). "Manhole covers vanish in the night". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "10,000 manhole covers vanish - Fingers pointed at Growing craze for Drugs, SNAP lottery". The Telegraph. Kolkata: ABP Group. 7 September 2004. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Word of the Year 2017: Shortlist". Oxford Languages. 0 Oxford University Press. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Meaning of newsjacking in English". Lexico. Oxford University Press/Dictionary.com. 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Benefits of Recycling Scrap Metal". Retrieved 2011-04-04.

- "OSHA Guidelines for Recycling Scrap Metal". Global Trade Metal Portal.

- Hartman, Roy A. (2009). "Recycling". Encarta. Archived from the original on 2008-04-14.

- "Steel Recycling Rates at a Glance" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-15. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- "Recycling steel appliances". Stell Recycling Institute. 2014. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- "End-of-life vehicle recycling process". Retrieved 2016-01-18.

- "Facts About Steel Recycling". Archived from the original on 2009-08-25. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- "Steel". Retrieved 2009-07-13.

- M.A. Reuter; K. Heiskanen; U. Boin; A. Van Schaik; E. Verhoef; Y. Yang; G. Georgalli, eds. (November 2005). "13" (Book). The metrics of material and metal ecology: harmonizing the resource, technology, and environmental cycles. Developments in Mineral Processing. 16. Elsevier. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-444-51137-9.

- "Information on Recycling Steel Products". WasteCap of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- "Ferrous Scrap Metal". Retrieved 2011-04-24.

- Archived January 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Archived January 13, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scrap metal. |

| Look up scrap in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |