Seneca Glass Company

Seneca Glass Company used to be the largest manufacturer of tumblers (drinking glasses) in the United States. The company was also known for its high-quality lead stemware, which was hand-made for nearly a century. Customers included Eleanor Roosevelt, Lyndon Johnson, the president of Liberia, the Ritz Carlton Hotel, Tiffany's, and Neiman-Marcus.

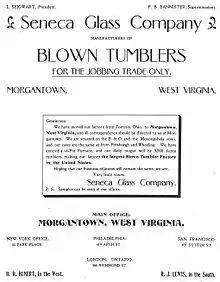

Seneca Glass Company logo from advertisement in 1905 Glass and Pottery World magazine. Plant was located in Morgantown, West Virginia, U.S. | |

| Type | Corporation |

|---|---|

| Industry | Glass manufacturing |

| Fate | Sold |

| Predecessor | Fostoria Glass Company |

| Successor | Seneca Crystal Incorporated (bankrupt in 1983) |

| Founded | 1891 (Production officially started January 1, 1892.) |

| Founder | Otto Jaeger, Leopold Sigwart, George Truog, August Boehler, Joseph Kammerer, Edward Kammerer |

| Defunct | 1982 |

| Headquarters | |

Key people | Leopold Sigwart, August Boehler, Joseph Kammerer |

| Products | lead-blown tumblers and stemware |

| Revenue | $2 million (1969) |

Number of employees | 250 (1897) |

The firm's first glass plant was located in Fostoria, Ohio. The company took possession of the plant on January 1, 1892, after it was vacated by the Fostoria Glass Company. Otto Jaeger was the first president of Seneca Glass Company, and he had been part of the Fostoria Glass Company management team. Like Jaeger, many of the new company's original leaders were German craftsmen.

In 1896, the firm moved to Morgantown, West Virginia, and continued to produce high-quality decorated glassware. A second plant was built in 1911 to produce tumblers and less-elaborate ware. During the 1950s, Seneca introduced its Driftwood Casual table setting pattern in an attempt to capture a less formal segment of the glassware market. This pattern was produced for nearly 30 years, and became especially important to the company as formal glassware became less popular.

In 1982, the company was sold to a group of investors that renamed the firm Seneca Crystal Incorporated. The firm filed for bankruptcy in 1983. Today, the Seneca Glass Company building is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and contains small retail shops and offices.

Regional history

Wheeling

Wheeling, Virginia was an early glass producing center in what was, during the 1820s, the American "West".[1] The city is located in Ohio County near the northernmost tip of what was the commonwealth of Virginia, which became part of West Virginia during the American Civil War. Wheeling had an advantage of the Ohio River as a transportation resource, and coal was available in the area as a fuel. Wheeling was also connected to the eastern United States by the National Road, and by the end of the 1840s major cities in Ohio were also connected. By the 1850s, railroads added to the area's transportation superiority. As the leading producers of glass in the region, Wheeling and Ohio's Belmont County (located across the river from Wheeling), eventually became sources of glassmaking talent for Ohio and Indiana.[Note 1] Among the talent developed in Wheeling was Otto Jaeger—future president of Seneca Glass Company. Jaeger was born in Germany in 1853, and came to America in 1866. He was taught the skill of engraving glass while still a teenager. In 1877, he began practicing his trade at the J. H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company glass works in Wheeling.[3]

Fostoria

In 1886, northwest Ohio began an economic boom period after a highly productive natural gas well was drilled in Hancock County.[4] The community of Fostoria, straddles three counties: Hancock, Seneca, and Wood.[5] Although gas was not found in the immediate Fostoria area, local government leaders constructed a pipeline from a nearby well in Wood County, and this enabled Fostoria to participate in the rush to lure manufacturers to the area.[6] In addition to gas and cash incentives, Fostoria had five railroad lines running through the city.[Note 2]

In response to incentives from Fostoria government leaders, a group of glass men from Wheeling organized a glassmaking company. During July 1887, Fostoria Glass Company was incorporated in West Virginia, but its factory was built in Fostoria, Ohio. Otto Jaeger was one of the directors of the new company.[8]

The Fostoria Glass Company was Fostoria's second (Mambourg Glass Company was first) of over a dozen glass factories to produce in the city.[9] Fostoria's gas boom did not last long. By 1891, the supply of natural gas was becoming depleted. The Fostoria Glass Company decided to move to West Virginia—a homecoming for its management.

Cumberland

During the 1880s, a group of glassmakers (and neighbors) from the Black Forest region of Germany moved to Cumberland, Maryland, to work in the city's glass factories. These men were skilled in art glassmaking, and hoped to someday start their own business where they could fully utilize their talents. During 1891, it became known that the Fostoria Glass Company planned to move away from Fostoria. The Black Forest glassmakers held a meeting on August 10, and formed a company to buy the soon-to-be vacated Fostoria glass works.[10] The German investor group selected another German, Otto Jaeger, to be their leader. Jaeger had been part of the Fostoria Glass Company management team, and was experienced in glass etching and engraving. The Fostoria plant and its permanent equipment were sold for $20,000 (over $500,000 in 2013 dollars) to the German investors during the Fall of 1891.[11][Note 3] Although the company's plant was in Fostoria, Ohio, it was granted its charter in West Virginia on December 4, 1891.[13] One commonly made mistake is the assumption that Seneca Glass Company was located in Ohio's Seneca County. While most of Fostoria is in Seneca County, the Seneca Glass South Vine Street plant was located in Hancock County, a few blocks west of the Seneca County border.[14] The shareholders of the new glass company named their firm after the Seneca Indians.[10]

Startup

Otto Jaeger assembled an experienced and highly skilled workforce for the Seneca Glass Company. Fostoria Glass Company took only 60 employees to West Virginia, leaving over half of its workforce in Fostoria. Many of these workers sought employment with the Seneca Glass Company—where they could continue to work in the same (South Vine Street) factory. Jaeger also had the highly skilled investor/glassmen from Cumberland, Maryland. Among these men were George Trough, August Boehler, Leopold Sigwart, and Edward and Joseph Kammerer.[Note 4] Otto Jaeger became president, while Edward Kammerer was vice president and general manager. Trough was secretary. Thus, the company's leaders and shareholders consisted of glassworkers instead of bankers or wealthy businessmen. Jaeger, Kammerer, and Trough were also elected to the board of directors, as were Boehler and Sigwart.[12]

The new company began blowing lead glassware on December 29, 1891—before Fostoria Glass had officially moved out of the factory.[12] Fostoria Glass "vacated this building officially December 31, 1891, with Seneca following on the premises January 1, 1892".[18][Note 5]

Fostoria operations

With its experienced workforce, production proceeded at the Seneca Glass works with no problems. The company advertised itself as a "manufacturer of fine lead blown table and bar goods", and promised "fine etching for advertising purposes".[20] The original plant was considered large for the time, with three buildings and a furnace with a capacity of 12 pots.[8]

Despite occasional shutdowns caused by low gas pressure (gas was the fuel used in the production process), production and sales were successful enough that capacity was increased to 38 pots in 1892.[21] The plant occupied 2.5 acres (1.0 ha), and was adjacent to three railroads.[22] About 200 people were employed by the company.[23] Because the production method used by the company emphasized handmade products, the workforce was highly skilled and well paid. Production of the glassware began around ceramic pots. Each pot contained molten glass created by melting a batch of ingredients inside the furnace. A workstation was adjacent to the pot, and manned by a glass–blower and his small production crew.[24] The company gained a reputation for high-quality glassware, and its glass works ranked first in the country in the production of blown tumblers.[25]

Management change

By 1895, the glass works employed over 230 people. Late in the year, production stopped as the workforce (which was non-union) went on strike because of unsatisfactory working conditions. The strike lasted from December 13 until January 17, 1896. During the work stoppage, a group of investors led by Leopold Sigwart removed Otto Jaeger as president. Jaeger resisted the change, causing the Sigwart group to install a new lock on the president's office. In protest, Edward Kamerer resigned as plant manager. Sigwart was elected president, and Kamerer was replaced as plant manager by his brother, Joseph.[26] The new management team successfully restarted the business. Sales were excellent during 1896, as employees worked overtime to keep up with demand. Production of tumblers amounted to "3,000 dozen daily".[27] Tumblers with an etching of presidential candidate William McKinley were especially popular.[27]

Morgantown

In the Fall of 1896, it was announced that the company would move to Morgantown, West Virginia. Morgantown was a desirable location because of transportation, fuel, and raw materials—and a cash subsidy. River transportation between Pittsburgh and Morgantown improved during the 1890s because of a new river lock on the Monongahela River. Railroad transportation became available after the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad connected Morgantown to the nation's railroad network. Oil and gas had recently been discovered in the area, providing more options for fuel in addition to the coal that was abundant in the area.[28] Good quality sand, used as a raw material for glassmaking, was available nearby in both the river and mountains.[29] The Seneca Glass Company had additional reasons to move to Morgantown. It received free land, low-priced gas, and $20,000 (over $500,000 in 2013 dollars) as enticement to move.[28]

The move was temporarily delayed after a legal complaint by Otto Jaeger filed in Hancock County Court.[30] However, a November settlement allowed the company to move. The building remained vacant until 1905, when it became the site for the Seneca Wire and Manufacturing Company.[31]

Glass works

The company's Morgantown glass works was constructed in 1896 and 1897. Production began in January 1897.[32] The plant, which is still standing, is located on Beechhurst Avenue, with access to the Monongahela River and Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. The furnace had 14 pots. An advertisement in the December 1896 edition of a glass trade magazine announced the move.[17]

The original facility included a furnace/blowing room, a lehr room, packing area, and warehouse. It also had smaller rooms where the glass was decorated.[33] The furnace/blowing room is mostly brick, and contains a huge smokestack. The room measures 80 feet (24.4 m) long by 80 feet (24.4 m) wide, and is one story plus a basement. The furnace is about 28 feet (8.5 m) in diameter and 9 feet (2.7 m) high. The lehr room is one-story, and measures about 60 feet (18.3 m) long by 60 feet (18.3 m) wide.[33] This room is where the glass was gradually cooled in ovens–a process called annealing.[34]

In 1902, the a fire damaged portions of the interior of the facility.[35] Losses from the fire were estimated to be $50,000 ($1.3 million in 2013 dollars), and 350 people temporarily had no place to work.[36] After the fire, the plant was repaired and additions were made to the original structure. The company also constructed a new two-story building, which was designed by prominent local architect Elmer F. Jacobs. More expansions were made during the 1920s and in 1947.[37]

New charter

The company was granted a new West Virginia charter in 1905. Major shareholders were Leopold Sigwart, Otto Sigwart, August Boehler, and J. A. Kammerer. Each held 120 shares of stock—totaling to 480 of the 873 total shares outstanding. Among the 16 remaining shareholders were Joseph Stenger (75 shares), George Truog (30 shares), and Frances Bannister (8 shares).[38] The company was always owned by a small group of stockholders, and the founders and their families managed the company throughout its existence. Otto Sigwart, who became president of the company in 1895, was eventually succeeded by another founder of the company, August Boehler. After Boehler became president, Sigwart worked as Vice President of the company for many years. He also managed the company's Factory B for the first few years of its existence, and was succeeded as manager of that plant by his son Charles. A third founder, Joseph A. Kammerer, became president in 1917. Kammerer served as president until his death in 1941.[39] At that time, Charles F. Boehler (brother of August Boehler) became president. In 1959, a newspaper noted that the Seneca Glass Company "president, vice president, and secretary–treasurer are descendants of the men who organized the company...a Kammerer is president, a Sigwart vice president, and a Stenger secretary–treasurer".[10] Among other family members in the business were Harry G. Kammerer, who was company president in 1959, and Harry's stepson John W. Weimer, who also became president.[39][40] Other family members served as officers of the company. Among those family members was Louis W. Stenger, who served as "an official with the Seneca Glass Co. for more than 40 years".[41] Another example is James Sigwart, who was Vice President of Seneca Glass Company when he died in 1950.[42]

Star City

Seneca Glass Company opened a second plant, known as "Plant B" in 1911.[43] This plant was located in Star City, West Virginia, about two miles from the Morgantown works. Plant B employed about 80 people. Products were mostly undecorated tumblers. Lime, instead of lead, was used to make the glass in two small tanks. The glassware was hand blown.[43] The plant was originally managed by Otto Sigwart, who had been president of the company earlier in his career. Sigwart was well-liked by the local members of the American Flint Glass Workers union. In 1914, Otto's son Charles became manager.[44] The plant operated until the 1930s.[45]

Production

The Seneca Glass Company used European glass production methods learned by their founders in Germany.[46] The glass was lead flint glass, which is made mostly from silica, potash, and oxide of lead. This type of glass has more sparkle and shine than flint glass made from lime.[47] Using technology from the 1890s and earlier, the glassblower's assistant (the gatherer) used a hollow pipe to extract molten glass from a pot.[48] A pot was about 40 inches in diameter, and Seneca's pots held 2,000 pounds (907.2 kg) of batch.[48][49] The glass blower and his crew used air, hand tools, and molds to shape the glass into the desired form. The glass appears orange, and then yellow, while it is still being shaped. In some cases, a glazer was used to smooth edges of the glass with small jets of flame.[48] Once the glass had the correct shape, it was then placed in a lehr, which is a long oven used for annealing, a process where the glass is gradually cooled. Without annealing, the glass would easily shatter. In the case of the glassware made at Seneca's Morgantown plant, it took almost 2 hours for the glass to move through the lehr.[46] Some of the finished glass would be cut, engraved, and/or polished. Glass with gold or silver trim added would be reheated to fuse the trim to the glass.[48]

Although old European glass production methods were used throughout the company's existence. technology was not entirely shunned by the founders. Otto Sigwart, with Peter Momper, received a patent for a mold in 1894.[50] August Stenger received a patent in 1898 for a machine that cut and smoothed tumblers.[51] Otto Sigwart received another patent in 1899. This patent was for a way to put stems on goblets.[52] Employee Anton Roemisch received a patent in 1900 for an apparatus for glazing and finishing glassware.[53]

Products

During its early years, Seneca Glass Company was the largest producer of Tumblers in the United States. It specialized in etched designs on its glassware, such as an advertisement for a hotel or bar. The company gradually became known for its high quality table ware. Seneca products were sold through premium outlets such as Wanamaker's, Marshall Field's, Tiffany's, and Neiman Marcus.[13] Its dinnerware was found in the Ritz Carlton hotel, and on international steam ship lines. It was also used in American embassies throughout the world. Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, and his wife, chose Seneca's Epicure pattern for their personal table ware.[54] Eleanor Roosevelt and one of Liberia's presidents were also purchasers of glassware made by Seneca Glass Company.[55] A few of Seneca's stemware designs were patented. Inventors were company founders or their relatives: Truog, Stenger, Kammerer, and Weimer.[Note 6]

The glass used for the glassware was made in a variety of colors, including a yellow and various shades of red, green, and blue.[45] Different colors of glass were created by adding to the batch of ingredients used to make the glass. For example, adding iron to the batch causes the glass to take a shade of green.[48] The recipes for different colors of glass were often kept secret, and sometimes only passed down from father to son.[60]

During the 1940s, colorless glass was popular. In 1953, the company started producing its Driftwood Casual dinnerware pattern, which was intended for informal dining. The decision to produce a less-formal product proved wise, as formal dinnerware became less popular during the next decade. The Driftwood pattern was popular, and produced for 30 years. The company introduced other informal dining patterns during the 1970s, although these were not as successful as Driftwood[45]

Legacy

The quality of Seneca Glass Company's glassware is indisputable. Its products were sold abroad and in American's finest outlets. From a business point-of-view, the remarkable aspect of Seneca Glass Company is its longevity—especially since it continued to use 1890s technology for nearly 100 years. Similar Fostoria glass companies, such as Butler Art Glass Company and Novelty Glass Company, did not last 5 years. The Butler Art Glass Company made various types of colored glass, and described itself as "a manufacturer of cathedral glass and glass color tiles."[61] The company incorporated in 1887, and made glass for only 15 months.[62] Fostoria's Novelty Glass Company produced "fine lead blown tumblers" and stemware.[7] Incorporators included some supervisory personnel from the Fostoria Glass Company, yet it operated only during 1891 and 1892.[63]

Otto Jaeger, the ousted first president of Seneca Glass Company, eventually returned to Wheeling, West Virginia. In 1901, he founded the Bonita Art Glass Company. The Wheeling company employed 100 people, and specialized in decorating china and glass. Bonita Art Glass products were exported, and the company also imported products manufactured overseas.[3]

George Truog (1861-1932) left the Seneca Glass Company and returned to Cumberland, Maryland. He founded the Maryland Glass Etching Works in 1893. Truog, who was born in Italy, was an expert at etching glass using acid. His business decorated glassware, and it was one of the best. Not only was Truog very artistic, but his etching was permanent—unlike some other decorating methods of the time, such as painting.[64] Truog's Cumberland home (George Truog House) was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1986.[65]

Today, the former Seneca Glass Company plant in Morgantown still stands. It is known as Seneca Center, and is the home of over 20 businesses.[66] The structure was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.[67]

Notes and references

- Notes

- In 1880, Belmont County ranked sixth in the nation in glass production, while Ohio County, West Virginia, (location of Wheeling), ranked seventh. The top five counties were in Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey.[2]

- Fostoria's five railroads, sometimes listed in advertisements by Fostoria glass companies in 1891, were: the Lake Erie and Western Railroad; the Columbus, Hocking Valley and Toledo Railway; the Toledo and Ohio Central Railway; the New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad (a.k.a. the Nickel Plate Railroad); and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.[7]

- The sale price for the Fostoria factory and equipment is either $20,000 or $10,000—depending on the source. Paquette's book, using a Fostoria newspaper as its source, states that Otto Jaeger made the purchase for $20,000.[12] Maryland sources, say the Cumberland investment group spent $10,000.[10] A logical assumption is that Jaeger spent $10,000, and the Cumberland investors also contributed $10,000—but this has not been verified.

- Paquette's book notes that Leopold Sigwart had several ways to spell his surname, and uses "Seigwart".[15] A March 1896 advertisement for Seneca Glass uses "Sigwart" as the spelling.[16] Later in the year (December) another Seneca Glass Company ad used the "Seigwart" spelling.[17] A 1959 Cumberland newspaper (Sigwart's original American hometown) uses the "Sigwart" spelling.[10]

- The Fostoria Ohio Glass Association agrees with the January 1892 official startup date for Seneca Glass Company, as posted on its web site.[19]

- George Truog and Harry G. Kammerer received patents on the design for drinking ware in 1913 and 1951, respectively.[56][57] Louis Stenger and John Weimer received patents in 1953 and 1970, respectively.[58][59]

- References

- Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 78

- Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 11

- "Otto Jaeger". Ohio County Public Library in partnership with Wheeling National Heritage Area Corporation. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- Murray 1992, p. 11

- Murray 1992, p. 12

- Murray 1992, p. 13

- Fostoria Novelty Glass Company (advertisement) 1891, p. 16

- Paquette 2002, p. 180

- "Fostoria, Ohio Glass Association". Fostoria, Ohio Glass Association. Archived from the original on December 18, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- Hunt, J. William (April 12, 1959). "Across the Desk". Cumberland Times. p. 10.

One Of The Nation's Leading Art Glass Companies Was Organized Here Nearly 70 Years Ago

- Paquette 2002, p. 182

- Paquette 2002, p. 214

- Page & Frederiksen 1995, p. VIII

- "Ohio, Hancock County, Detailed Map". Online Searches, LLC. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- Paquette 2002, p. 249

- Seneca Glass Company (advertisement) 1896, p. 35

- Seneca Glass Company (Morgantown advertisement) 1896, p. 11

- Murray 1992, p. 69

- "Fostoria, Ohio Glass Association". Fostoria, Ohio Glass Association. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- Murray 1992, pp. 68–69

- Paquette 2002, p. 215

- Murray 1992, p. 70

- Murray 1992, p. 71

- United States Bureau of foreign and domestic commerce (Dept. of Commerce) 1917, p. 51

- Glass & Pottery World (March edition) 1896, p. 36

- Paquette 2002, pp. 215–216

- Glass & Pottery World (June edition) 1896, p. 30

- Fleming 1985, p. 1 section 8

- Heaster, Frank M. (November 16, 1969). "Mason-Dixonland Notebook". Morgantown Dominion Post. p. 47.

- Paquette 2002, p. 216

- Paquette 2002, p. 217

- Clement 1973, p. 2

- Fleming 1985, p. 2 section 7

- Paquette 2002, p. 471

- Fleming 1985, p. 1 section 7

- "Glass Factory Burns". Janesville Daily Gazette. June 13, 1902. p. 1.

- Fleming 1985, pp. 1–4 section 7

- West Virginia, West Virginia Governor & West Virginia Legislature 1907, p. 58

- "Obituary". Cumberland Evening Times. June 5, 1941. p. 13.

…Joseph Anthony Kammerer, president of the Seneca Glass Company who died…

- "Vacations To Begin In City Glass Plants". Morgantown Post. June 30, 1961. p. 1.

- "Louis Stenger Passes Away". Morgantown Post. September 4, 1959. p. 1.

- "W. Va. Deaths". Charleston Daily Mail. September 14, 1950. p. 28.

- Hennen, Reger & White 1913, p. 18

- Goldstrom 1914, p. 43

- Page & Frederiksen 1995, p. X

- Cochran, Wendell (November 16, 1969). "Seneca Glass". Morgantown Dominion Post. p. 40.

- Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, pp. 19–21

- "Glass Industry Here Is Over Century Old". Morgantown Post. August 22, 1959. pp. 7–8.

- Clement 1973, p. 4

- US patent 527,801, "Glass Mold", issued 1894–10–23

- US patent 601,685, "Machine for Cutting and Smoothing Tumblers", issued 1898–4–5

- US patent 624,389, "Machine for Putting Stems and Feet on Goblets", issued 1899–5–2

- US patent 664,058, "Apparatus for Glazing and Finishing Articles of Glassware", issued 1900–12–18

- Page & Frederiksen 1995, p. IX

- Fleming 1985, p. 2 of Section 8

- US patent D44717, "Design for a Glass Vessel", issued 1913–10–7

- US patent D163806, "Goblet or Similar Article", issued 1951–7–3

- US patent D170666, "Glass", issued 1953–10–20

- US patent D217630, "Tumbler or Similar Article", issued 1970–5–19

- Murray 1992, p. 61

- Paquette 2002, p. 184

- Paquette 2002, pp. 184–186

- Paquette 2002, pp. 205–206

- "Maryland Glass Etching Works". Cumberland Glass. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- Kurtze 1986, p. 1

- "Seneca Center". Seneca Center. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- Fleming 1985, p. 1 section 1

- Cited works

- Clement, Daniel (1973). "Seneca Glass Company" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. OCLC 20229044.

- Fleming, Dolores A. (1985). "Seneca Glass Company Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form. National Park Service.

- Fostoria Novelty Glass Company (advertisement) (1891). "Fostoria Novelty Glass Company". China, Glass and Lamps (May 13).

- Glass & Pottery World (June edition) (1896). "McKinley Tumblers". Glass & Pottery World. Chicago: Trade Magazine Association. IV (6). OCLC 1390202.

- Glass & Pottery World (March edition) (1896). "(Unnamed article in column on left side of page 38)". Glass & Pottery World. Chicago: Trade Magazine Association. IV (3). OCLC 1390202.

- Goldstrom, Andrew (1914). "Morgantown, W. VA". The American Flint. Toledo, OH: The American Flint Glass Workers of North America. 5 (5).

- Hennen, Ray V.; Reger, David B.; White, I.C. (1913). Marion, Monongalia and Taylor counties – West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey. Wheeling, WV: Wheeling News Litho. Co. OCLC 15654857.

- Kurtze, Peter E. (1986). "George Truog House" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form. National Park Service.

- Murray, Melvin L. (1992). Fostoria, Ohio Glass II. Fostoria, OH: M. L. Murray. p. 184. OCLC 27036061.

- Page, Bob; Frederiksen, Dale (1995). Seneca Glass Company, 1891-1983 : a stemware identification guide. Greensboro, NC: Page-Frederiksen Pub. Co. : Replacements [distributor]. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-88997-702-7. OCLC 33078185.

- Paquette, Jack K. (2002). Blowpipes, Northwest Ohio Glassmaking in the Gas Boom of the 1880s. Xlibris Corp. p. 559. ISBN 1-4010-4790-4. OCLC 50932436.

- Seneca Glass Company (advertisement) (1896). "Seneca Glass Company". Glass and Pottery World. Chicago: Trade Magazine Association. IV (3). OCLC 1390202.

- Seneca Glass Company (Morgantown advertisement) (1896). "Seneca Glass Company". Glass and Pottery World. Chicago: Trade Magazine Association. IV (12). OCLC 1390202.

- United States Bureau of foreign and domestic commerce (Dept. of Commerce) (1917). The Glass Industry. Report on the cost of production of glass in the United States. Washington. OCLC 5705310. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- Weeks, Joseph Dame; United States Census Office (1884). Report on the manufacture of glass. Washington: Government Printing Office. pp. 1152. OCLC 2123984.

report on the manufacture of glass.

- West Virginia; West Virginia Governor; West Virginia Legislature (1907). "New Agreement – Seneca Glass Company. – (Resident.)". Public Documents: West Virginia Corporation Report of Secretary of State. Charleston. 2. OCLC 13484972.

External links

- Glass Making, Glass Blowing, Glass Cutting: "Seneca Glass" 1974 Part 1 on YouTube

- Glass Making, Glass Blowing, Glass Cutting: "Seneca Glass" 1974 Part 2 on YouTube

- Seneca Glass on YouTube

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. WV-6, "Seneca Glass Company Factory, Beechurst Avenue between Sixth & Eighth Streets, Morgantown, Monongalia County, WV", 42 photos, 4 measured drawings, 17 data pages, 3 photo caption pages

- Morgantown History Museum: Seneca Glass