Shakuhachi

The shakuhachi (Japanese: 尺八、しゃくはち, pronounced [ˌʃakʊˈhatʃi]) (Chinese: 尺八; pinyin: chǐbā) is a Japanese and ancient Chinese longitudinal, end-blown flute that is made of bamboo.

A Tozan school shakuhachi flute, blowing edge up. Left: top view, four holes. Right: bottom view, fifth hole. | |

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | woodwind |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 421.111.12 (Open single end-blown flute with fingerholes) |

| Developed | 7th century AD |

| Part of a series on |

| Fuke Zen |

|---|

|

| People |

|

| Philosophy |

| Places |

|

| Topics |

| Literature |

|

It was originally introduced from China into Japan in the 7th century and reached its peak in the Edo period (17th–18th century). The oldest shakuhachi in Japan is currently stored in Shōsō-in, Nara. The shakuhachi introduced into Japan changed its form and scale many times after that, and the present shakuhachi was completed in the Edo period in the 17th century.[1][2] The shakuhachi is traditionally made of bamboo, but versions now exist in ABS and hardwoods. It was used by the monks of the Fuke Zen of Zen Buddhism in the practice of suizen (吹禅, blowing meditation).

The instrument is tuned to the minor pentatonic scale.

Overview

The name shakuhachi means "1.8 shaku", referring to its size. It is a compound of two words:

- shaku (尺) is an archaic unit of length equal to 30.3 centimeters (0.994 English foot) and subdivided in ten subunits.

- hachi (八) means "eight", here eight sun, or tenths, of a shaku.

Thus, "shaku-hachi" means "one shaku eight sun" (54.54 centimeters), the standard length of a shakuhachi. Other shakuhachi vary in length from about 1.3 shaku up to 3.6 shaku. Although the sizes differ, all are still referred to generically as "shakuhachi".

Shakuhachi are usually made from the root end of madake (真竹) (Phyllostachys bambusoides) bamboo culm and are extremely versatile instruments. Professional players can produce virtually any pitch they wish from the instrument, and play a wide repertoire of original Zen music, ensemble music with koto, biwa, and shamisen, folk music, jazz, and other modern pieces.

Much of the shakuhachi's subtlety (and player's skill) lies in its rich tone colouring, and the ability for its variation. Different fingerings, embouchures and amounts of meri/kari can produce notes of the same pitch, but with subtle or dramatic differences in the tone colouring. Holes can be covered partially (1/3 covered, 1/2, 2/3, etc.) and pitch varied subtly or substantially by changing the blowing angle. The Honkyoku (本曲) pieces rely heavily on this aspect of the instrument to enhance their subtlety and depth.

Unlike a recorder, where the player blows into a duct—a narrow airway over a block which is called a "fipple"—and thus has limited pitch control, the shakuhachi player blows as one would blow across the top of an empty bottle (though the shakuhachi has a sharp edge to blow against called utaguchi) and therefore has substantial pitch control. The five finger holes are tuned to a minor pentatonic scale with no half-tones, but using techniques called meri メリ and kari カリ, in which the blowing angle is adjusted to bend the pitch downward and upward, respectively, combined with embouchure adjustments and fingering techniques the player can bend each pitch as much as a whole tone or more. Pitches may also be lowered by shading (kazashi カザシ) or partially covering finger holes. Since most pitches can be achieved via several different fingering or blowing techniques on the shakuhachi, the timbre of each possibility is taken into account when composing or playing thus different names are used to write notes of the same pitch which differ in timbre. The shakuhachi has a range of two full octaves (the lower is called otsu 乙/呂, the upper, kan 甲) and a partial third octave (dai-kan 大甲) though experienced players can produce notes up to E7 (2637.02 Hz) on a 1.8 shakuhachi.[3][4] The various octaves are produced using subtle variations of breath, finger positions and embouchure.

In traditional shakuhachi repertoire instead of tonguing for articulation like many western wind instruments, hitting holes (oshi 押し / osu オス) with a very fast movement is used and each note has its corresponding repeat fingerings e.g. for repeating C5 (リ) the 5th hole (D5's tone hole) is used.[4]

A 1.8 shakuhachi produces D4 (D above Middle C, 293.66 Hz) as its fundamental—the lowest note it produces with all five finger holes covered, and a normal blowing angle. In contrast, a 2.4 shakuhachi has a fundamental of A3 (A below Middle C, 220 Hz). As the length increases, the spacing of the finger holes also increases, stretching both fingers and technique. Longer flutes often have offset finger holes, and very long flutes are almost always custom made to suit individual players. Some honkyoku, in particular those of the Nezasaha (Kimpu-ryū) school are intended to be played on these longer flutes.

Due to the skill required, the time involved, and the range of quality in materials to craft bamboo shakuhachi, one can expect to pay from US$1,000 to US$8,000 for a new or used flute. Because each piece of bamboo is unique, shakuhachi cannot be mass-produced, and craftsmen must spend much time finding the correct shape and length of bamboo, curing it for more or less of a decade in a controlled environment and then start shaping the bore for almost a year using Ji 地 paste — many layers of a mixture including tonoko powder (砥の粉) and seshime and finished with urushi lacquer — for each individual flute to achieve correct pitch and tonality over all notes. Specimens of extremely high quality, with valuable inlays, or of historical significance can fetch US$20,000 or more. Plastic or PVC shakuhachi have some advantages over their traditional bamboo counterparts: they are lightweight, extremely durable, nearly impervious to heat and cold, and typically cost less than US$100. Shakuhachi made of wood are also available, typically costing less than bamboo but more than synthetic materials. Nearly all players, however, prefer bamboo, citing tonal qualities, aesthetics, and tradition.

History

Shakuhachi is derived from the Chinese bamboo-flute. The bamboo-flute first came to Japan from China during the 7th century.[5][6] Shakuhachi looks like the Chinese instrument Xiao, but it is quite distinct from it.

During the medieval period, shakuhachi were most notable for their role in the Fuke sect of Zen Buddhist monks, known as komusō ("priests of nothingness," or "emptiness monks" 虚無僧), who used the shakuhachi as a spiritual tool. Their songs (called "honkyoku") were paced according to the players' breathing and were considered meditation (suizen) as much as music.[7]

Travel around Japan was restricted by the shogunate at this time, but the Fuke sect managed to wrangle an exemption from the Shōgun, since their spiritual practice required them to move from place to place playing the shakuhachi and begging for alms (one famous song reflects this mendicant tradition, "Hi fu mi, hachi gaeshi", "One two three, pass the alms bowl", 一二三鉢返の調). They persuaded the Shōgun to give them "exclusive rights" to play the instrument. In return, some were required to spy for the shogunate, and the Shōgun sent several of his own spies out in the guise of Fuke monks as well. This was made easier by the wicker baskets (tengai 天蓋) that the Fuke wore over their heads, a symbol of their detachment from the world.

In response to these developments, several particularly difficult honkyoku pieces, e.g., Distant Call of the Deer (Shika no tone 鹿の遠音), became well known as "tests": if you could play them, you were a real Fuke. If you couldn't, you were probably a spy and might very well be killed if you were in unfriendly territory.

With the Meiji Restoration, beginning in 1868, the shogunate was abolished and so was the Fuke sect, in order to help identify and eliminate the shōgun's holdouts. The very playing of the shakuhachi was officially forbidden for a few years. Non-Fuke folk traditions did not suffer greatly from this, since the tunes could be played just as easily on another pentatonic instrument. However, the honkyoku repertoire was known exclusively to the Fuke sect and transmitted by repetition and practice, and much of it was lost, along with many important documents.

When the Meiji government did permit the playing of shakuhachi again, it was only as an accompanying instrument to the koto, shamisen, etc. It was not until later that honkyoku were allowed to be played publicly again as solo pieces.

Shakuhachi has traditionally been played almost exclusively by men in Japan, although this situation is rapidly changing. Many teachers of traditional shakuhachi music indicate that a majority of their students are women. The 2004 Big Apple Shakuhachi Festival in New York City hosted the first-ever concert of international women shakuhachi masters. This Festival was organized and produced by Ronnie Nyogetsu Reishin Seldin, who was the first full-time Shakuhachi master to teach in the Western Hemisphere. Nyogetsu also holds 2 Dai Shihan (Grand Master) Licenses, and has run KiSuiAn, the largest and most active Shakuhachi Dojo outside Japan, since 1975.

The first non-Japanese person to become a shakuhachi master is the American-Australian Riley Lee. Lee was responsible for the World Shakuhachi Festival being held in Sydney, Australia over 5–8 July 2008, based at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music.[8][9] Riley Lee played the shakuhachi in Dawn Mantras which was composed by Ross Edwards especially for the Dawn Performance, which took place on the sails of the Sydney Opera House at sunrise on 1 January 2000 and was televised internationally.[10]

Acoustics

The shakuhachi creates a harmonic spectrum that contains the fundamental frequency together with even and odd harmonics and some blowing noise.[11] Five tone holes enable musicians to play the notes D-F-G-A-C-D. Cross (or fork) fingerings, half-covering tone holes, and meri/kari blowing cause pitch sharpening, referred to as intonation anomaly.[12] Especially the second and third harmonic exhibit the well-known shakuhachi timbre. Even though the geometry of the shakuhachi is relatively simple, the sound radiation of the shakuhachi is rather complicated.[13] Sound radiating from several holes and the natural asymmetry of bamboo create an individual spectrum in each direction. This spectrum depends on frequency and playing technique.

Notable players

The International Shakuhachi Society maintains a directory of notable professional, amateur, and teaching shakuhachi players.[14]

Recordings

The primary genres of shakuhachi music are:

- honkyoku (traditional, solo)

- sankyoku (ensemble, with koto and shamisen)

- shinkyoku (new music composed for shakuhachi and koto, commonly post-Meiji era compositions influenced by western music)[15]

Recordings in each of these categories are available; however, more albums are catalogued in categories outside the traditional realm. As of 2018, shakuhachi players continue releasing records in a variety of traditional and modern styles.[16]

The first shakuhachi recording appeared in the United States in the late 1960s. Gorō Yamaguchi recorded A Bell Ringing in the Empty Sky for Nonesuch Explorer Records on LP, an album which received acclaim from Rolling Stone at the time of its release.[17] One of the pieces featured on Yamaguchi's record was "Sokaku Reibo," also called "Tsuru No Sugomori" (Crane's Nesting).[18] NASA later chose to include this track as part of the Golden Record aboard the Voyager spacecraft.[19]

In the film industry

Shakuhachi are often used in modern film scores, for example those by James Horner. Films in which it is featured prominently include: The Karate Kid parts II and III by Bill Conti, Legends of the Fall and Braveheart by James Horner, Jurassic Park and its sequels by John Williams and Don Davis, and The Last Samurai by Hans Zimmer and Memoirs of a Geisha by John Williams.

Renowned Japanese classical and film-score composer Toru Takemitsu wrote many pieces for shakuhachi and orchestra, including his well-known Celeste, Autumn and November Steps.

Western contemporary music

The Australian Shakuhachi Master and composer Jim Franklyn has composed an impressive number of works for solo shakuhachi, also including electronics. After an extensive research and consultation with virtuoso Yoshikazu Iwamoto, British composer John Palmer has pushed the virtuosity of the instrument to the limit by including a wide range of extended techniques in Koan (1999, for shakuhachi and ensemble). In Carlo Forlivesi's composition for shakuhachi and guitar Ugetsu (雨月) "The performance techniques present notable difficulties in a few completely novel situations: an audacious movement of ‘expansion’ of the respective traditions of the two instruments pushed as they are at times to the limits of the possible, the aim being to have the shakuhachi and the guitar playing on the same level and with virtuosity (two instruments that are culturally and acoustically so dissimilar), thus increasing the expressive range, the texture of the dialogue, the harmonic dimension and the tone-colour."[20] American composer and performer Elizabeth Brown plays shakuhachi and has written many pieces for the instrument that build on Japanese traditions while diverging with more modern arrangement, orchestration, melodic twists or harmonic progressions.[21][22][23] New York-born musician James Nyoraku Schlefer both plays, teaches, and composes for shakuhachi. In addition, composer Carson Kievman has employed the instrument in many works from "Ladies Voices" in 1976 to "Feudal Japan" in the upcoming parallel world opera "Passion Love Gravity" in 2020-21.

Jazz

Brian Ritchie of the Violent Femmes formed a Jazz quintet in 2002 called The N.Y.C. Shakuhachi Club. They play Avant-garde jazz versions of tradition American Folk & Blues songs with Ritchie's shakuhachi playing as the focal point. In 2004 they released their debut album on Weed Records.

Synthesized shakuhachi

The sound of the shakuhachi is also featured from time to time in electronica, pop and rock, especially after being commonly shipped as a "preset" instrument on various synthesizers and keyboards beginning in the 1980s.[24] Here is a list of well-known tracks where the sound of an emulated, or sampled shakuhachi can be heard:

| Year | Artist or band | Album | Song, range, notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | Duran Duran | Rio | "Save a Prayer" [full track] |

| 1983 | Osamu Kitajima | Face to Face | "Tracks 2,3,5,7,9" [Tacoma Records TAK-7107] |

| 1985 | Tangerine Dream | Le Parc | "Yellowstone Park" [0:00–0:05, 2:23–2:50] |

| 1985 | Tangerine Dream | Legend OST | "Opening" [0:00–0:30] |

| 1985 | Tangerine Dream | Legend OST | "Unicorn Theme" [0:00–0:10] |

| 1985 | Dire Straits | Brothers in Arms | "Ride Across the River" [0:00–0:06] |

| 1985 | Echo & the Bunnymen | Songs to Learn & Sing | "Bring On the Dancing Horses" [0:45–0:53 and in every chorus that follows] |

| 1985 | Wang Chung | To Live and Die in L.A. (OST) | "Wake Up, Stop Dreaming" [???–???] |

| 1985 | Tears for Fears | Head Over Heels (single) | "When in Love with a Blind Man" (b-side) [0:44–0:54, 1:32–1:36, 1:45–1:56] |

| 1985 | Evada | Ooh, My Love | "Ooh, My Love" [0:45–0:56,1:57-2:02,3:10-3:22,4:40-5:12] |

| 1986 | Alpha Blondy | Jerusalem | "Jerusalem" [0:00–0:13] |

| 1986 | Erste Allgemeine Verunsicherung | Geld oder Leben! | "Fata Morgana" [0:02–0:09] |

| 1986 | Shriekback | Oil and Gold | "Coelocanth" [whole song] |

| 1986 | Coil | Horse Rotorvator | "The First Five Minutes After Death" [1:15–1:45, 2:38–3:38, 4:30–end], morbid shakuhachi. |

| 1986 | Peter Gabriel | So | "Sledgehammer" [0:00–0:16, 3:16–3:34] |

| 1986 | Bad Boys Blue | Come Back and Stay | "Come Back and Stay" [0:19–0:31] |

| 1987 | Coil | Gold Is the Metal | "The First Five Minutes After Violent Death" [0:30–1:30, 2:45–3:45, etc., morbid shakuhachi. |

| 1987 | Coil | Unnatural History III | "Music for Commercials": Liqueur [0:41–1:26] Natural Gas [03:15–04:00] |

| 1987 | Roger Waters | Radio K.A.O.S. | "Me or Him" [0:09–0:22, 1:27–1:35, 2:06–2:20, etc.] |

| 1987 | Rush | Hold Your Fire | "Tai Shan" |

| 1988 | And Also the Trees | The Millpond Years | "The Sandstone Man" [0:33–0:39, 3:25–4:36] |

| 1988 | Vangelis | Direct | "The will of the wind" [1:02–1:53, 2:22–3:13] |

| 1988 | Sade | Stronger Than Pride | "Love Is Stronger Than Pride" [0:28–0:33, 2:08–2:14, 2:28–2:33, 3:08–3:30, etc.] |

| 1988 | Marshall Jefferson | Open Our Eyes | "Open Our Eyes" [0:12 and throughout] |

| 1989 | The Sugarcubes (Björk's ex-band) | Here Today, Tomorrow Next Week! | "Pump" [2:06–2:22] |

| 1990 | Enigma | MCMXC a.D. | "Sadeness (Principles of Lust, Part 1)" [1:14–1:54, 2:56–3:16] |

| 1990 | Enigma | MCMXC a.D. | "Knocking on Forbidden Doors" [1:13 and throughout] |

| 1991 | Gregorian | Sadisfaction | "So Sad" [0:18–0:40, 1:04–1:14, 1:38–1:48, 2:12–2:22] |

| 1991 | Klaus Schulze | Beyond Recall | "Airlights" [0:00–0:05, 0:15–0:20, 0:40–0:50, 1:00–1:05, etc.] |

| 1992 | LTJ Bukem | Demon's Theme / A Couple Of Beats | "Demon's Theme" [3:47–4:38, 6:52–7:10] |

| 1992 | Snap! | Exterminate! | "Exterminate! Feat. Nikki Harris" [2:20–2:52, etc.] |

| 1993 | Dave Brubeck | Late Night Brubeck | "Koto Song" [4:30–9:50] – Bobby Militello's flute emulation |

| 1993 | Naughty by Nature | 19 Naughty III | "Hip Hop Hooray" [0:02–0:08] |

| 1993 | Future Sound of London | Cascade | "Cascade 1" [2:05–6:25] + "Cascade 6" [1:40–2:15], opener/closer tracks |

| 1994 | Future Sound of London | Lifeforms | "Little Brother" [4:00–5:13(end)], closer track |

| 1994 | Klaus Schulze as Richard Wahnfried | Trancelation | "The End – Someday" [2:17–2:36] |

| 1994 | Paul Hardcastle | Hardcastle | "Lazy Days" [0:00–0:10] |

| 1994 | The Primitive Painter | The Primitive Painter | "Orgon Akkumulator" [throughout] |

| 1995 | Michael Bolton | Greatest Hits (1985-1995) | "Can I Touch You... There?" [0:00–0:04, 3:26–3:50, 4:24–5:07] |

| 1995 | Juno Reactor | Beyond the Infinite | "Samurai" [scattered throughout] |

| 1995 | The Pharcyde | Labcabincalifornia | "Hey You" [throughout] |

| 1995 | Force & Styles | Pretty Green Eyes | "Pretty green eyes" [01:26–1:45,05:20-05:50] |

| 1995 | Greg Adams | Hidden Agenda | "Burma Road" [0:40 and throughout] |

| 1995 | Enya | The Memory of Trees | "China Roses", "Tea-House Moon" |

| 1996 | Toshio Iwai | SimTunes | Piper, blue "bug" available voice, Low C3 to C5 |

| 1998 | Symphony X | Twilight in Olympus | "Lady of the Snow" [0:00–0:26] |

| 2000 | Kosmonova | Discover the World | "Discover the World" [main melody] |

| 2000 | Olson Brothers | Fly on the Wings of Love | "Fly on the Wings of Love" [0:08–0:17] |

| 2001 | Incubus | Morning View | "Aqueous Transmission" and "Circles" |

| 2003 | Linkin Park | Meteora | "Nobody's Listening" |

| 2004 | Air | Talkie Walkie | "Cherry Blossom Girl" |

| 2004 | Autumn Tears | Eclipse | "At a Distance" [0:32–0:56, 1:19–2:15, 2:37–3:04, 3:47–4:15] |

| 2010 | Andrea Carri | Partire | "Dove Andremo?" [0:31–1:21] |

| 2011 | Dj Dean meets Barbarez | Double Trouble | "Hamburg Rulez Reloaded" [0:44–1:50] |

| 2011 | Paul Hardcastle | Hardcastle VI | "Rainforest / What's Going On" [4:23–4:32] |

| 2011 | Zenithrash | Restoration Of The Samurai World | "Ritual","Harakiri","The Samurai Metal" |

| 2011 | Devin Townsend | Ghost | "Fly" |

| 2011 | Joshua Iz | Magnetron | "Magnetron (Simoncino Protho Remix)" |

| 2012 | Adam Tucker | Music by Peter Hallock | "Night Music" |

| 2012 | Moullinex | Flora | "Let Your Feet (Do The Work)" |

| 2013 | Nagy Ákos | "Soli(e)tude" | |

| 2015 | Fort Romeau | Saku | "Saku" |

See also

- Embouchure

- Hotchiku (a similar, end-blown bamboo flute)

- List of shakuhachi players

- Quena (a similar flute from South America)

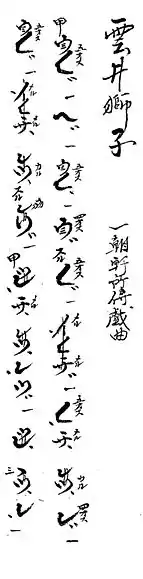

- Shakuhachi musical notation

- Shakuhachi players (category)

References

- 新都山流 心安らぐあたたかな音色 尺八.

- 公益財団法人 都山流尺八学会.

- "Getting started | The European Shakuhachi Society". shakuhachisociety.eu. Retrieved 2017-06-21.

- Koga, Masayuki (July 24, 2016). Shakuhachi: Fundamental Technique Guidance. USA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 1 edition. pp. 101, 28. ISBN 978-1535460705.

- Yohmei Blasdel, Christopher; Kamisango, Yuko (June 1, 2008). The Shakuhachi: A Manual for Learning (Includes Practice CD). Printed Matter Press. ISBN 978-1933606156.

- Levenson, Monty H. "Origins & History of the Shakuhachi". www.shakuhachi.com. Retrieved 2018-09-26.

- Keister, Jay (2004). "The Shakuhachi as a Spiritual Tool: A Japanese Buddhist Instrument in the West". Asian Music. 35 (2): 104–105.

- https://www.shakuhachi.com/V-WSF08.html

- The Empty Bell – Blowing Zen, Into The Music, ABC Radio National, accessed 24 October 2008

- "Dawn Mantras (1999)". Ross Edwards. Retrieved 2014-07-30.

- Yoshikawa, Shigeru (2017). "Japanese Flutes and Their Musical Acoustic Peculiarities". In Schneider, Albrecht (ed.). Studies in Musical Acoustics and Psychoacoustics. R. Bader, M. Leman and R.I. Godoy (Series Eds.): Current Research in Systematic Musicology. Volume 4. Cham: Springer. pp. 1–47. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47292-8_1. ISBN 978-3-319-47292-8.

- Ando, Yoshinori (1986). "Input admittance of shakuhachis and their resonance characteristics in the playing state". Journal of the Acoustical Society of Japan (E). 7 (2): 99–111. doi:10.1250/ast.7.99.

- Ziemer, Tim (2014). Sound Radiation Characteristic of a Shakuhachi with different Playing Techniques (PDF). International Symposium on Musical Acoustics (ISMA). pp. 549–555. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "People whose speciality is shakuhachi". The International Shakuhachi Society. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- "Shakuhachi Terms – WSF2018". wsf2018.com. Retrieved 2018-09-25.

- Nelson, Ronald. "The International Shakuhachi Society". www.komuso.com. Retrieved 2018-09-25.

- "20 Sixties Albums You've Never Heard". Rolling Stone. 2014-05-22. Retrieved 2018-09-25.

- Nelson, Ronald. "The International Shakuhachi Society". www.komuso.com. Retrieved 2018-09-25.

- "Voyager – Music on the Golden Record". voyager.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2018-09-25.

- ALM Records ALCD-76

- Sullivan, Jack. "Elizabeth Brown, Mirage," American Record Guide, January/February 2014, p. 83.

- Carl, Robert. Elizabeth Brown – Mirage, liner notes, Brooklyn, NY: New World Records, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Elizabeth Brown website. Pieces with Shakuhachi or Traditional Japanese Instruments. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- The "E-mu Emulator II shakuhachi" is number nine in "20 Sounds That Must Die" by David Battino, Keyboard Magazine, October 1995

Further reading

- Henry Johnson, The shakuhachi: roots and routes, Amsterdam, Brill, 2014 (ISBN 978-90-04-24339-2)

- Iwamoto Yoshikazu, The Potential of the Shakuhachi in Contemporary Music, “Contemporary Music Review”, 8/2, 1994, pp. 5–44

- Tsukitani Tsuneko, The shakuhachi and its music, in Alison McQueen Tokita, David W. Huges (edited by), The Ashgate Research Companion to Japanese Music 7, Aldershot, Ashgate, 2008, pp. 145–168

- Riley Lee (1992). "Yearning For The Bell; a study of transmission in the shakuhachi honkyoku tradition", Thesis, University of Sydney

- Seyama Tōru, The Re-contextualisation of the Shakuhachi (Syakuhati) and its Music from Traditional/Classical into Modern/Popular, “the world of music”, 40/2, 1998, pp. 69–84

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shakuhachi. |