Siege of Osaka

The Siege of Osaka (大坂の役, Ōsaka no Eki, or, more commonly, 大坂の陣 Ōsaka no Jin) was a series of battles undertaken by the Tokugawa shogunate against the Toyotomi clan, and ending in that clan's destruction. Divided into two stages (winter campaign and summer campaign), and lasting from 1614 to 1615, the siege put an end to the last major armed opposition to the shogunate's establishment. The end of the conflict is sometimes called the Genna Armistice (元和偃武, Genna Enbu), because the era name was changed from Keichō to Genna immediately following the siege.

| Siege of Osaka | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the late Sengoku Period and the early Edo period | |||||||

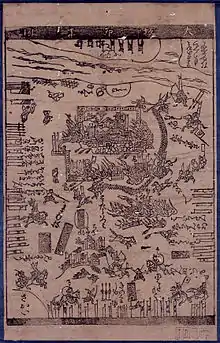

Illustration from François Caron's book: "The Burning of Osaka Castle" | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Tokugawa shogunate and its loyalist banners: |

Toyotomi clan and its loyalist retainers:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Tokugawa Ieyasu Tokugawa Hidetada Todo Takatora Ii Naotaka Matsudaira Tadanao Date Masamune Honda Masanobu Honda Tadatomo † Satake Yoshinobu Asano Nagaakira Maeda Toshitsune Uesugi Kagekatsu Mōri Hidenari Sanada Nobuyoshi (instead of Nobuyuki) |

Toyotomi Hideyori (death being debated) Yodo-dono † Sanada Yukimura † Gotō Mototsugu † Akashi Takenori Chōsokabe Morichika Mōri Katsunaga † Kimura Shigenari † Ōno Harunaga † Sanada Daisuke † Ban Naoyuki † Oda Nobukatsu (defection to Tokugawa side) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

164,000 (winter) 150,000 (summer) |

120,000 (winter) 60,000 (summer) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Minimal | Thousands killed | ||||||

Background

When Toyotomi Hideyoshi died in 1598, Japan came to be governed by the Council of Five Elders, among whom Tokugawa Ieyasu possessed the most authority. After defeating Ishida Mitsunari in the battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Ieyasu essentially seized control of Japan for himself, and abolished the Council. In 1603, the Tokugawa shogunate was established, with its capital at Edo. Hideyori and his mother Yodo-dono were allowed to stay at Osaka Castle, a fortress that had served as Hideyoshi's residence and that was he found himself in a fief valued at 657,400 koku. Hideyori remained confined to the castle for several years. In addition, as a mechanism of control, it was agreed that in the year 1603 he would marry the daughter of Hidetada, Senhime who was related to both clans. Ieyasu sought to establish a powerful and stable regime under the rule of his own clan; only the Toyotomi, led by Hideyoshi's son Toyotomi Hideyori under the influence of his mother Yodo-dono, remained an obstacle to that goal.

In 1611 Hideyori finally left Osaka, meeting with Ieyasu for two hours at Nijō Castle. Ieyasu was surprised by Hideyori's behavior, contrary to popular belief that the boy was just "useless". This belief had been spread by Katagiri Katsumoto, Hideyori's personal guardian since 1599 assigned by Ieyasu, and who had the intention of dissuading any aggression against the heir.

In 1614, the Toyotomi clan rebuilt Osaka Castle. At the same time, the head of the clan sponsored the rebuilding of Hōkō-ji in Kyoto. These temple renovations included the casting of a great bronze bell, with inscriptions that read "May the state be peaceful and prosperous" (国家安康 kokka ankō), and "May noble lord and servants be rich and cheerful" (君臣豊楽 kunshin hōraku). The shogunate interpreted "kokka ankō" (国家安康) as shattering Ieyasu's name (家康) to curse him, and also interpreted "kunshin hōraku" (君臣豊楽) to mean "Toyotomi's force (豊臣) will rise again," which meant treachery against the shogunate. Tensions began to grow between the Tokugawa and the Toyotomi clans, and only increased when Toyotomi began to gather a force of rōnin and enemies of the shogunate in Osaka. Ieyasu, despite having passed the title of Shōgun to his son in 1605, nevertheless maintained significant influence.

Despite Katagiri Katsumoto's attempts to mediate the situation, Ieyasu found the ideal pretext to take a belligerent attitude against Yodo-dono and Hideyori. The situation worsened in September of that year, when the news reached Edo that in Osaka they were grouping a large quantity of rōnin at the invitation of Hideyori.

Katsumoto proposed that Yodo-dono be sent to Edo as a hostage with the desire to avoid hostilities, which she flatly refused. Suspecting him of trying to betray the Toyotomi clan, Yodo-dono banished Katsumoto and several other servants accused of treason from Osaka castle, sending them to the service of the Tokugawa clan. Consequently, any possibility of reaching an agreement with the shogunate was dissolved.

This last maneuver of Yodo-dono, who acted as the guardian of Hideyori, led to the beginning of the siege of Osaka.

Winter campaign

In November of 1614, Tokugawa Ieyasu decided not to let this force grow any larger, and led 164,000 men to Osaka. (The count does not include the troops of Shimazu Tadatsune, an ally of the Toyotomi cause who nevertheless did not send troops to Osaka.)

The siege began on 19 November, when Ieyasu led 3,000 men across the Kizu River, destroying the fort there. A week later, he attacked the village of Imafuku with 1,500 men, against a defending force of 600. With the aid of a squad wielding arquebuses, the shogunate forces claimed another victory. Several more small forts and villages were attacked before the siege of Osaka Castle itself began on 4 December.

The Sanada-maru was an earthwork barbican defended by Sanada Yukimura and 7,000 men, on behalf of the Toyotomi. The Shōgun's armies were repeatedly repelled, and Sanada and his men launched a number of attacks against the siege lines, breaking through three times. Ieyasu then resorted to artillery (including 17 imported European cannons and 300 domestic wrought iron cannons) and men digging under the walls.

Bombing of Osaka Castle

Ieyasu, realizing that the castle would not fall easily and after consulting with his top advisers, ordered a limited bombing which began on January 8, 1615. For three consecutive days, his forces bombarded the fortress at 10 o'clock at night and at dawn. Meanwhile, miners were making tunnels under the walls and arrows were thrown inwards with messages requesting the surrender of the occupants. By day 15, with no response from the besieged, Ieyasu began an incessant bombardment that had a mainly psychological effect to diminish the morale of the defenders. The stone bases of Japanese castles were invulnerable to the artillery of the era and the structure of the castle remained virtually undamaged.

Realizing that the defenses were extremely strong, Ieyasu tried to convince Sanada Yukimura to change sides. Yukimura, who felt a strong antipathy for Ieyasu, rejected the bribe and made the attempt public. Ieyasu then bribed another captain, a commander named Nanjo Tadashige, asking him to open the castle gates. The attempted treason was discovered and Nanjo beheaded, so Ieyasu changed his strategy. Ieyasu ordered his men to deliberately bomb Yodo-dono's quarters, and when they had found the range, a cannon hit its target, killing two of her maids.

During the night of the 16th, Ban Naotsugu, in charge of the defenses of one of the west side doors, carried out a night attack on the troops of Hachisuka Yoshishige, killing several enemies before retreating. The bombing continued the next day, on the mournful anniversary of Toyotomi Hideyoshi's death. Ieyasu thought that on that day Hideyori would be in the temple dedicated to his father, so he ordered that his forces fire towards the place. The projectile almost hit Hideyori's head, hitting one of the pillars of Yodo-dono's quarters, who became terrified and pressed to reach an arrangement with the shogunate.

Peace negotiations

On January 17, Ieyasu sent Honda Masazumi, accompanied by Lady Acha, to meet with Kyōgoku Tadataka, son of Ohatsu, younger sister of Yodo-dono. During the meeting, Lady Acha assured Ohatsu that Ieyasu had no ill will to Hideyori and that he wished to forgive him, but Hidetada was stubborn about taking the castle, so he had thousands of miners working in tunnels under the pits. On the other hand Honda assured that Ieyasu would allow Hideyori to keep Osaka as his fief, but in case he wanted to leave he would give him another one with higher income, besides that all his captains and soldiers would be given free transit when leaving or they could stay inside if they wanted to, but he would need some hostages as a sign of goodwill.

Ohatsu conveyed the terms to Yodo-dono who, in terror, asked Ōno Harunaga, Oda Nobukatsu, and Hideyori's top seven advisers to accept the terms of the surrender. Lady Acha and Honda met again with Ohatsu, and they told him that the outer pit should be filled by Ieyasu's men. On the 21st day, Oda delivered their children as hostages and Hideyori sent Kimura to Chausayama to close the agreement. Ieyasu issued a document, sealed with blood from his finger and signed also by Hidetada, which said:

That the rōnin in the castle are not found guilty; that Hideyori's income remain the same as before; that Yodo-dono is not asked to live in Edo; that if Hideyori chooses to leave Ōsaka he may choose any other province as his fiefdom; that his person is inviolable.

On January 22, Ieyasu received a solemn oath from Hideyori and Yodo-dono that Hideyori would not rebel against Ieyasu or Hidetada and that he would consult any matter directly with him. Both Honda Tadamasa and Honda Masayuri were entrusted to dismantle the castle's exterior defenses, so the soldiers of the shogunate tore down the walls and filled the outer moat. Hideyori did complain indignantly to the workers that this had not been part of the arrangement, but the response he received was that they only followed Ieyasu's orders. Honda Masazumi blamed the workers for having misunderstood their instructions because they were already filling the interior moat as well. Although the work stopped momentarily, soon the soldiers of the shogunate continued, so Yodo-dono sent one of her bridesmaids and Ōno to Kyoto. Several days later Ieyasu gave an elusive official response, where he assured that since he had signed an eternal peace, the walls were not necessary.

End of the peace treaty

Ieyasu left Osaka and left for Kyoto on January 24, meeting with the emperor at a formal hearing on the 28th, where he informed the emperor that the war had come to an end. Hidetada remained in place to supervise the work of destruction of the defenses, arriving in Edo on March 13. By then, news reached the capital that Osaka was once again meeting rōnin. This information led Ieyasu to order Hideyori to leave Osaka's fief.

Even from the moment when peace was being signed, Osaka had proposed to launch a night attack on the Tokugawa camp, although it was finally decided not to do so. Shortly after Hideyori began to receive reports of the true intentions of Ieyasu, so they began the work of digging out the moats and attracting rōnin to the fortress.

Hideyori and his main generals agreed that unlike the first campaign, this time it would be appropriate to take the offensive. Also, it was arranged to secure the areas surrounding Osaka and take Kyoto to control the emperor, so that he would declare Ieyasu to be a rebel against the Imperial throne. Following the rumors of what the Osaka Army planned, the population of Kyoto began to flee from the city, and even a commander of the shogunate, Furuta Shigenari, was sentenced to death, suspected of being part of a plot to burn down Kyoto and apprehend the emperor.

Ieyasu left Shizuoka on May 3 to Nagoya, where his ninth son married on the 11th of the same month in the castle of that city. The next day he met a traitor from the Osaka camp, Oda Yuraku, who informed him that there were several factions within the castle, that the war councils rarely ended in anything conclusive and that Yodo-dono generally intervened in all matters. Later, he went to Nijō Castle, where he arrived on May 17 and met there on the 21 or 22 with Hidetada, who arrived with the troops ready to go to Osaka.[1]

Summer campaign

In April 1615, Ieyasu received word that Toyotomi Hideyori was gathering even more troops than in the previous November, and that he was trying to stop the filling of the moat. Toyotomi forces (often called the Western Army) began to attack contingents of the Shōgun's forces (the Eastern Army) near Osaka.

On 26 May (Keichō 20, 29th day of 4th month) at the Battle of Kashii, Osaka forces under the command of Ono Harufusa and Ban Danemon engaged with forces of Asano Nagaakira, an ally of the Shōgun. Osaka forces sustained a loss and Ban Danemon was killed.

On 2 June (Keichō 20, 6th day of 5th month), the Battle of Dōmyōji took place. Osaka forces tried to stop the Tokugawa forces approaching from Yamato Province along the Yamato-gawa river. Two Osaka generals, Gotō Matabei and Susukida Kanesuke, were killed in action. Osaka forces commander Sanada Yukimura engaged in a battle with Date Masamune forces, but soon retreated towards Osaka Castle. Tokugawa forces did not pursue Sanada.

The same day Chōsokabe Morichika and Tōdō Takatora battled at Yao. Another battle took place at Wakae around the same time, between Kimura Shigenari and Ii Naotaka. Chōsokabe's forces achieved victory, but Kimura Shigenari was deflected by the left wing of Ii Naotaka's army. The main Tokugawa forces moved to assist Todo Takatora after Shigenari's death, and Chōsokabe withdrew for the time being.

The fall of Osaka Castle

After another series of shogunate victories on the outskirts of Osaka, the summer campaign came to a head at the battle of Tennōji. Hideyori planned a hammer-and-anvil operation, in which 55,000 men would attack the center of the Eastern Army, while a second force, 16,500 men led by Kyōgoku Tadataka, Ishikawa Tadafusa, and Kyōgoku Takatomo, would flank them from the rear.[1] Another contingent waited in reserve. Ieyasu's army was led by his son, the Shōgun Tokugawa Hidetada, and numbered around 155,000. They moved in four parallel lines, prepared to make flanking maneuvers of their own. Mistakes on both sides nearly ruined the battle, as Hideyori's rōnin split off from the main group, and Hidetada's reserve force moved up without orders from the main force.

In the end, Hideyori's commander Sanada Yukimura was killed, destroying the morale of the Western Army. The smaller force led directly by Hideyori sallied forth from Osaka Castle too late, and was chased right back into the castle by the advancing enemies; there was no time to set up a proper defense of the castle, and it was soon ablaze and pummeled by artillery fire.

The people who were in the castle began to escape. Hidetada knew that his daughter was in the castle, so he sent Ii Naotaka to save her. Senhime managed to escape with her son Toyotomi Kunimatsu (Hideyori's son) accompanied by other women. Kaihime fled with Oiwa no Kata (Hideyori's concubine) and Nāhime (Hideyori's daughter). While they retreated, Kaihime personally defended Nāhime from Tokugawa troops. Hideyori and Yodo-dono took refuge in a fireproof warehouse, as much of the castle was in flames. Ōno Harunaga sent Hideyori's wife, Senhime, with his father Hidetada to be forgiven, and to plead for the life of her husband and mother-in-law.

Without waiting for answers, Toyotomi Hideyori and Yodo-dono committed seppuku in the flames of Osaka castle, ending the Toyotomi legacy. The final major uprising against Tokugawa rule was put to an end, leaving the shogunate unchallenged for approximately 250 years.

Theory

According to an account by an employee of the Dutch East India Company in Hirado, several daimyō set the castle on fire and attempted to defect to Ieyasu. Hideyori executed them by throwing them off the castle wall but could not extinguish the fire, causing his suicide. The account also stated that about 10,000 people died.[2] History indicates that the legendary swordsman Miyamoto Musashi participated in the battle on the Toyotomi side, though he has no recorded accomplishments in this battle.

Aftermath

Hideyori's son Toyotomi Kunimatsu (age 8) was captured by the shogunate and beheaded in Kyoto. According to legend, before his beheading, little Kunimatsu bravely blamed Ieyasu for his betrayal and brutality against Toyotomi clan. Nāhime, daughter of Hideyori, was not sentenced to death. Ohatsu and Senhime were able to save Nāhime's life and adopted her; she later became a nun at Kamakura's Tōkei-ji. Hideyoshi's grave, along with Kyoto's Toyokuni Shrine, were destroyed by the shogunate. Chōsokabe Morichika was beheaded on May 11. There are also records of pillaging and mass rapes by Tokugawa forces at the closing of the siege.

The bakufu obtained 650,000 koku at Osaka and started rebuilding Osaka Castle. Osaka was then made a han (feudal domain), and given to Matsudaira Tadayoshi. In 1619, however, the shogunate replaced Osaka Domain with Osaka Jodai, placed under the command of a bugyō who served the shogunate directly; like many of Japan's other major cities, Osaka was for the remainder of the Edo period not part of a han under the control of a daimyō. A few daimyō including Naitō Nobumasa (Takatsuki Castle, Settsu Province 20,000 koku) and Mizuno Katsushige (Yamato Koriyama, Yamato Province 60,000 koku) moved to Osaka.

The Toyotomi clan was then disbanded.

After the fall of the castle, the shogunate announced laws including ikkoku ichijō (一国一城)[3] (one province can contain only one castle) and Bukeshohatto (or called Law of Buke, which limits each daimyō to own only one castle and obey the castle restrictions). The shogunate's permission had to be obtained prior to any castle construction or repair from then on. Many castles were also forced to be destroyed as a result of compliance with this law.

Despite finally uniting Japan, Ieyasu's health was failing. During the one-year campaign against the Toyotomi clan and its allies, he received wounds that significantly shortened his life. Roughly one year later on June 1, 1616, Tokugawa Ieyasu, the third and last of the great unifiers, died at the age of 75, leaving the shogunate to his descendants.

In popular culture

The siege is the subject of the Hiroshi Inagaki's historical drama "Ōsaka-jō monogatari" (engl. The Tale of Osaka Castle, UK; some other English titles: "Daredevil in the Castle", "Devil in the Castle", "Osaka Castle Story") (1961) with Toshiro Mifune in the leading role.[4] It is also the backdrop for Tai Kato's musical film Brave Records of the Sanada Clan (1963).[5] The period of prolonged peace following the Siege of Osaka forms the backdrop to the film Harakiri (1962).[6]

The fall of Osaka is (for most of the characters) the final level in the Samurai Warriors series, also serving as the climax of Hattori Hanzō's, Ieyasu's and Yukimura's stories. Called the "Osaka Campaign", it compiles all the battles of the Winter and Summer Campaigns. In the computer game Shadow Tactics: Blades of the Shogun, the siege of Osaka castle is the setting of the first (and demo) mission. A manga titled Issak, was about a man who survived a betrayal of his own fellow student, who fled after the fall of the castle. Then, he went on to Europe, just to find and kill him in midst of Thirty Years War as a mercenary of the Palatinate, while his nemesis, a mercenary for the Spanish Empire.

See also

- Winter Campaign (大坂冬の陣 Osaka Fuyu no Jin)

- Battle of Imafuku

- Battle of Shigino

- Battle of Kizugawa

- Battle of Noda-Fukushima

- Siege of Sanada-maru

- Summer Campaign (大坂夏の陣 Osaka Natsu no Jin)

- Battle of Kashii

- Battle of Dōmyōji

- Battle of Yao

- Battle of Wakae

- Battle of Tennoji

References

- Turnbull, Stephen (2012). Osaka 1615: The Last Battle of the Samurai. Illustrated by Richard Hook. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781782000099.

- "Document on 17th century 'Siege of Osaka' found in Dutch national archives". The Mainichi. 2016-09-22. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- Jennifer Mitchelhill (2003). Castles of the Samurai: Power and Beauty. Kodansha International. p. 67. ISBN 978-4-7700-2954-6.

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0055267/

- "Sanada fūunroku" (in Japanese). Japanese Cinema Database. Archived from the original on 31 October 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- John Berra (2012). Japan 2. Intellect Books. pp. 151–153. ISBN 978-1-84150-551-0.

Bibliography

- Davis, Paul K. (2001). "Besieged: 100 Great Sieges from Jericho to Sarajevo." Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 激闘大坂の陣―最大最後の戦国合戦(2000). Gakken ISBN 978-4-05-602236-0

- 戦況図録大坂の陣―永き戦乱の世に終止符を打った日本史上最大規模の攻城戦(2004) 新人物往来社 ISBN 978-4-404-03056-6

- Turnbull, Stephen. (2006). "Osaka 1615: The Last Samurai Battle." Osprey Publishing, Westminster, MD.