Siege of Vienna

The Siege of Vienna, in 1529, was the first attempt by the Ottoman Empire to capture the city of Vienna, Austria. Suleiman the Magnificent, sultan of the Ottomans, attacked the city with over 100,000 men, while the defenders, led by Niklas Graf Salm, numbered no more than 21,000. Nevertheless, Vienna was able to survive the siege, which ultimately lasted just over two weeks, from 27 September to 15 October 1529.

| Siege of Vienna | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman wars in Europe and the Ottoman–Habsburg wars | |||||||

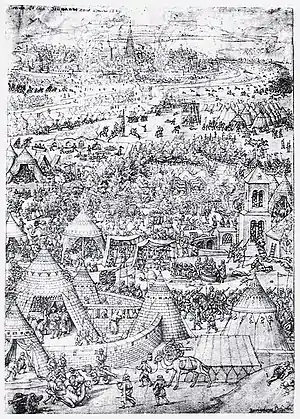

Contemporary 1529 engraving of clashes between the Austrians and Ottomans outside Vienna, by Bartel Beham | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Niklas Graf Salm (WIA) Philipp der Streitbare Wilhelm von Roggendorf |

Suleiman the Magnificent Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 17,000–21,000[2] |

c. 120,000–125,000 (only 100,000 were available during the siege)[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Unknown, with presumably high civilian fatalities[4] Something more than 1,500 dead (10% of the besieged)[5] | 15,000 wounded, dead or captured[4] | ||||||

The siege came in the aftermath of the 1526 Battle of Mohács, which had resulted in the death of Louis II, King of Hungary, and the descent of the kingdom into civil war. Following Louis' death, rival factions within Hungary selected two successors: Archduke Ferdinand I of Austria, supported by the House of Habsburg, and John Zápolya. Zápolya would eventually seek aid from, and become a vassal of, the Ottoman Empire, after Ferdinand began to take control of western Hungary, including the city of Buda.

The Ottoman attack on Vienna was part of the empire's intervention into the Hungarian conflict, and in the short term sought to secure Zápolya's position. Historians offer conflicting interpretations of the Ottoman's long-term goals, including the motivations behind the choice of Vienna as the campaign’s immediate target. Some modern historians suggest that Suleiman's primary objective was to assert Ottoman control over all of Hungary, including the western part (known as Royal Hungary) was then still under Habsburg control. Some scholars suggest Suleiman intended to use Hungary as a staging ground for an eventual invasion of Europe.[6]

The failure of the Siege of Vienna marked the beginning of 150 years of bitter military tension between the Habsburgs and Ottomans, punctuated by reciprocal attacks, and culminating in a second siege of Vienna in 1683.

Background

In August 1526, Sultan Suleiman I decisively defeated the forces of King Louis II of Hungary at the Battle of Mohács, paving the way for the Ottomans to gain control of south-eastern Hungary;[7] the childless King Louis was killed, possibly by drowning when he attempted to escape the battlefield.[8] His brother-in-law, Archduke Ferdinand I of Austria, brother of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, claimed the vacant Hungarian throne. Ferdinand won recognition only in western Hungary; while a noble called John Zápolya, from a power-base in Transylvania, challenged him for the crown and was recognised as king by Suleiman in return for accepting vassal status within the Ottoman Empire.[8][9] Thus Hungary became divided into three zones: Royal Hungary, Ottoman Hungary and the Principality of Transylvania, an arrangement which persisted until 1700.[10]

Following the Diet of Pozsony (modern Bratislava) on 26 October,[11] Ferdinand was declared king of Royal Hungary due to the agreement between his and Louis's families, cemented by Ferdinand's marriage to Louis's sister Anna and Louis's marriage to Ferdinand's sister Mary. Ferdinand set out to enforce his claim on Hungary and captured Buda in 1527, only to relinquish his hold on it in 1529 when an Ottoman counter-attack stripped Ferdinand of all his territorial gains.[12]

Prelude

Ottoman army

In the spring of 1529, Suleiman mustered a large army in Ottoman Bulgaria, with the aim of securing control over all of Hungary at his new borders by Ferdinand I and the Holy Roman Empire. Estimates of Suleiman's army vary widely from 120,000 to more than 300,000 men, as mentioned by various chroniclers.[13] As well as numerous units of Sipahi, the elite mounted force of the Ottoman cavalry, and thousands of janissaries, the Ottoman army incorporated a contingent from Moldavia and renegade Serbian warriors from the army of John Zápolya.[14] Suleiman acted as the commander-in-chief (as well as personally leading his force), and in April he appointed his Grand Vizier (the highest Ottoman minister), a Greek former slave called Ibrahim Pasha, as Serasker, a commander with powers to give orders in the sultan's name.[15]

Suleiman launched his campaign on 10 May 1529 and faced numerous obstacles from the onset.[16] The spring rains that are characteristic of south-eastern Europe and the Balkans were particularly heavy that year, causing flooding in Bulgaria and rendering parts of the route used by the army barely passable. Many large-calibre cannons and artillery pieces became hopelessly mired or bogged down, leaving Suleiman no choice but to abandon them,[17] while camels brought from the empire's Eastern provinces, not used to the difficult conditions, were lost in large numbers. Sickness and poor health became common among the janissaries, claiming many lives along the perilous journey.[18]

Suleiman arrived in Osijek on 6 August. On the 18th he reached the Mohács plain, to be greeted by a substantial cavalry force led by John Zápolya (which would later accompany Suleiman to Vienna), who paid him homage and helped him recapture several fortresses lost since the Battle of Mohács to the Austrians, including Buda, which fell on 8 September.[19] The only resistance came at Pozsony, where the Turkish fleet was bombarded as it sailed up the Danube.[16]

Defensive measures

As the Ottomans advanced towards Vienna, the city's population organised an ad-hoc resistance formed from local farmers, peasants, and civilians determined to repel the inevitable attack. The defenders were supported by a variety of European mercenaries, namely German Landsknecht pikemen and professional Spanish harquebusiers sent by Charles V.[20][21]

Queen Mary of Hungary, who was the sister of the King of Spain and Emperor (Charles I of Spain and V of the Empire), in addition to 1,000 German Landsknechts under Count Niklas Salm, sent a contingent of 700-800 Spanish harquebusiers. Only 250 Spanish survived.[5]

The Spanish were under the command of Marshal Luis de Ávalos, with captains Juan de Salinas, Jaime García de Guzmán, Jorge Manrique, and Cristóbal de Aranda. This elite infantry excelled in the defense of the northern area and with discretion fire prevented the Ottomans from settling in the Danube meadows, near the ramparts, where they could have breached with enough space to work. These elite soldiers also built additional palisades and trap pits that would be essential during the siege.

The Hofmeister of Austria, Wilhelm von Roggendorf, assumed charge of the defensive garrison, with operational command entrusted to a seventy-year-old German mercenary named Nicholas, Count of Salm, who had distinguished himself at the Battle of Pavia in 1525.[16] Salm arrived in Vienna as head of the mercenary relief force and set about fortifying the three-hundred-year-old walls surrounding St. Stephen's Cathedral, near which he established his headquarters. To ensure the city could withstand a lengthy siege, he blocked the four city gates and reinforced the walls, which in some places were no more than six feet thick, and erected earthen bastions and an inner earthen rampart, levelling buildings where necessary to clear room for defences.[16]

Siege

The Ottoman army that arrived in late September had been somewhat depleted during the long advance into Austrian territory, leaving Suleiman short of camels and heavy artillery. Many of his troops arrived at Vienna in a poor state of health after the tribulations of a long march through the thick of the European wet season. Of those fit to fight, a third were light cavalry, or Sipahis, ill-suited for siege warfare. Three richly dressed Austrian prisoners were dispatched as emissaries by the Sultan to negotiate the city's surrender; Salm sent three richly dressed Muslims back without a response.

As the Ottoman army settled into position, the Austrian garrison launched sorties to disrupt the digging and mining of tunnels below the city's walls by Ottoman sappers, and in one case almost capturing Ibrahim Pasha. The defending forces detected and successfully detonated several mines intended to bring down the city's walls, subsequently dispatching 8,000 men on 6 October to attack the Ottoman mining operations, destroying many of the tunnels, but sustaining serious losses when the confined spaces hindered their retreat into the city.[16]

More rain fell on 11 October, and with the Ottomans failing to make any breaches in the walls, the prospects for victory began to fade rapidly. In addition, Suleiman was facing critical shortages of supplies such as food and water, while casualties, sickness, and desertions began taking a toll on his army's ranks. The janissaries began voicing their displeasure at the progression of events, demanding a decision on whether to remain or abandon the siege. The Sultan convened an official council on 12 October to deliberate the matter. It was decided to attempt one final, major assault on Vienna, an "all or nothing" gamble.[22] Extra rewards were offered to the troops. However, this assault was also beaten back as, once again, the arquebuses and long pikes of the defenders prevailed.[23] After the failure of this assault on 14 October, with supplies running low and winter approaching Suleiman called off the siege the next day and ordered a withdrawal to Istanbul.[24][25]

Unusually heavy snowfall made conditions go from bad to worse. The Ottoman retreat was hampered by muddy roads through which their horses and camels struggled to pass. Pursuing Austrian horsemen made prisoner many stragglers but there was no Austrian counterattack. The Ottomans reached Buda on 26 October, Belgrade on 10 November and their destination, Istanbul, on 16 December.[26][27]

Aftermath

Some historians speculate that Suleiman's final assault was not necessarily intended to take the city but to cause as much damage as possible and weaken it for a later attack, a tactic he had employed at Buda in 1526. Suleiman would lead another campaign against Vienna in 1532, but it never truly materialised as his force was stalled by the Croatian Captain Nikola Jurišić during the Siege of Güns (Kőszeg).[4] Nikola Jurišić with only 700–800 Croatian soldiers managed to delay his force until winter closed in.[4][28] Charles V, now largely aware of Vienna's vulnerability and weakened state, assembled 80,000 troops to confront the Ottoman force. Instead of going ahead with a second siege attempt, the Ottoman force turned back, laying waste the south-eastern Austrian state of Styria in their retreat.[29] The two Viennese campaigns in essence marked the extreme limit of Ottoman logistical capability to field large armies deep in central Europe at the time.[30]

The 1529 campaign produced mixed results. Buda was brought back under the control of the Ottoman vassal John Zápolya, strengthening the Ottoman position in Hungary. The campaign left behind a trail of collateral damage in neighbouring Habsburg Hungary and Austria that impaired Ferdinand's capacity to mount a sustained counter-attack. However, Suleiman failed to force Ferdinand to engage him in open battle, and was thus unable to enforce his ideological claim to superiority over the Habsburgs. The attack on Vienna led to a rapprochement between Charles V and Pope Clement VII, and contributed to the Pope's coronation of Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor on February 24, 1530. The outcome of the campaign was presented as a success by the Ottomans, who used the opportunity to show off their imperial grandeur by staging elaborate ceremonies for the circumcision of princes Mustafa, Mehmed, and Selim.[31]

Ferdinand I erected a funeral monument for the German mercenary Nicholas, Count of Salm, head of the mercenary relief force dispatched to Vienna, as a token of appreciation of his efforts. Nicholas survived the initial siege attempt, but had been injured during the last Ottoman assault and died on 4 May 1530.[32] The Renaissance sarcophagus is now on display in the baptistery of the Votivkirche cathedral in Vienna. Ferdinand's son, Maximilian II, later built the Castle of Neugebaeude on the spot where Suleiman is said to have pitched his tent during the siege.[33]

References

- Shaw, Stanford J. (29 October 1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-521-29163-7. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- Turnbull says the garrison was "over 16,000 strong". The Ottoman Empire, p 50; Keegan and Wheatcroft suggest 17,000. Who's Who in Military History, p 283; Some estimates are just above 20,000, for example: "Together with Wilhelm von Roggendorf, the Marshal of Austria, Salm conducted the defense of Vienna with 16,000 regulars and 5,000 militia." Dupuy, Trevor, et al., The Encyclopedia of Military Biography, p 653.

- Turnbull suggests Suleiman had "perhaps 120,000" troops when he reached Osijek on 6 August. The Ottoman Empire, p 50; Christopher Duffy suggests "Suleiman led an army of 125,000 Turks". Siege Warfare: Fortresses in the Early Modern World 1494–1660, p 201. For higher estimates, see further note on Suleiman's troops.

- Turnbull, Stephen. The Ottoman Empire 1326–1699. New York: Osprey, 2003. p. 51

- https://repositorio.uam.es/bitstream/handle/10486/1235/17116_C6.pdf?sequence=1

- It was an "afterthought towards the end of a season of campaigning". Riley-Smith, p 256; "A last-minute decision following a quick victory in Hungary". Shaw and Shaw, p 94; Other historians, including Stephen Turnbull, regard the suppression of Hungary as the calculated prologue, to an invasion further into Europe: "John Szapolya [sic] became a footnote in the next great Turkish advance against Europe in the most ambitious campaign of the great Sultan's reign." Turnbull, p 50.

- "Battle of Mohács". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- "Louis II: king of Hungary and Bohemia". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- "Süleyman the Magnificent". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- Jean Berenger; C.A. Simpson (2014). A History of the Habsburg Empire 1273-1700. Routledge. pp. 189–190. ISBN 9781317895701.

- Turnbull, Stephen. The Ottoman Empire 1326–1699. New York: Osprey, 2003. p. 49

- Turnbull, Stephen. The Ottoman Empire 1326–1699. New York: Osprey, 2003. pp. 49–50

- Turnbull suggests Suleiman had "perhaps 120,000" troops when he reached Osijek on 6 August. Turnbull, p 50; Very high figures appear in nineteenth-century histories, for example that of Augusta Theodosia Drane in 1858, "more than 300,000 men"; such estimates may derive from contemporary accounts: the Venetian diarist Marino Sanuto, on 29 October 1529, for example, recorded the Turkish army as containing 305,200 men (mentioned in Albert Howe Lyber's The Government of the Ottoman Empire in the Time of Suleiman the Magnificent, p 107). Modern books sometimes repeat the higher figures—for example, Daniel Chirot, in The Origins of Backwardness in Eastern Europe, 1980, p 183, says "some 300,000 men besieged Vienna in 1529"; an alternative figure appears in Islam at War: "The sultan's army of 250,000 appeared before the gates of Vienna in the first siege of that great city", Walton, et al., 2003, p 104.

- E. Liptai: Magyarország hadtörténete I. Zrínyi Military Publisher 1984. ISBN 963-326-320-4 p. 165.

- In April, the diploma by which Suleiman confirmed Ibrahim Pasha's appointment as serasker included the following: "Whatever he says and in whatever manner he decides to regard things, you are to accept them as if they were the propitious words and respect-commanding decrees issuing from my own pearl-dispensing tongue." Quoted by Rhoads Murphey in Ottoman Warfare 1500–1700, p 136.

- Turnbull, p 50-1.

- "Siege of Vienna: Europe [1529]". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- Hans H.A. Hötte (2014). Atlas of Southeast Europe: Geopolitics and History. Volume One: 1521-1699. BRILL. p. 8. ISBN 9789004288881.

- Stavrianos, p 77.

- Ferdinand I had withdrawn to the safety of Habsburg Bohemia following pleas for assistance to his brother, Emperor Charles V, who was too stretched by his war with France to spare more than a few Spanish infantry to the cause.

- Reston, James Jr, Defenders of the Faith: Charles V, Suleyman the Magnificent, and the Battle for Europe, 1520–1536, Marshall Cavendish, 2009, pg. 288 ISBN 1-59420-225-7, ISBN 978-1-59420-225-4

- Spielman, p 22.

- Stavrianos, p 78.

- Early Modern Wars 1500–1775 p.18

- Holmes et al p.953

- Skaarup, Harold A. (2003). Siegecraft - No Fortress Impregnable. Lincoln, Nevada: iUniverse. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-595-27521-2.

- Hötte, Hans H. A. (2015). Atlas of Southeast Europe: Geopolitics and History. Volume One: 1521-1699. Leiden, Holland: BRILL. p. 8. ISBN 978-90-04-28888-1.

- Wheatcroft (2009), p. 59.

- Tracy, p 140.

- Riley-Smith, p 256.

- Şahin, Kaya (2013). Empire and Power in the Reign of Süleyman: Narrating the Sixteenth-Century Ottoman World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-1-107-03442-6.

- Entry on Salm. Dupuy, et al., p 653.

- Louthan, p 43.

Bibliography

- Early Modern Wars 1500–1775. London: Amber Books Ltd. 2013. ISBN 978-1-78274-121-3.

- Chirot, Daniel (1980). The Origins of Backwardness in Eastern Europe. ISBN 0-520-07640-0.

- Dupuy, Trevor N.; Johnson, Curt; Bongard, David. L. (1992). The Encyclopedia of Military Biography. I.B.Tauris & Co. ISBN 1-85043-569-3.

- Fisher, Sydney Nettleton (1979). The Middle East: A History (3rd ed.). Knopf. ISBN 0-394-32098-0.

- Holmes, Richard; Strachan, Hew; Bellamy, Chris; Bicheno, Hugh; Strachan, Hew (2001). The Oxford Companion to Military History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866209-9.

- Kann, Robert Adolf (1980). A History of the Habsburg Empire: 1526–1918. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04206-9.

- Keegan, John; Wheatcroft, Andrew (1996). Who's Who in Military History: From 1453 to the Present Day. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12722-X.

- Louthan, Howard (1997). The Quest for Compromise: Peacemakers in Counter-Reformation Vienna. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-58082-X.

- Lyber, Albert Howe (1913). The Government of the Ottoman Empire in the Time of Suleiman the Magnificent. Harvard University Press.

- Murphey, Rhoads (1999). Ottoman Warfare 1500–1700. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2685-X.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2002). The Oxford History of the Crusades. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280312-3.

- Sáez Abad, Rubén (2013), El Sitio de Viena, 1529. Zaragoza (Spain): HRM Ediciones. ISBN 978-8494109911.

- Şahin, Kaya (2013). Empire and Power in the Reign of Süleyman: Narrating the Sixteenth-Century Ottoman World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03442-6.

- Sellés Ferrando, Xavier (2000), "Carlos V y el primer cerco de Viena en la literatura hispánica del XVI", In: Carlos V y la Quiebra del Humanismo Político en Europa (1530-1558) : International Congress, Madrid (Spain) 3–6 July 2000].

- Shaw, Stanford Jay; Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29163-1.

- Spielman, John Philip (1993). The City and the Crown: Vienna and the Imperial Court. Purdue University Press. ISBN 1-55753-021-1.

- Stavrianos, Leften Stavros (2000). The Balkans Since 1453. London: Hurst. ISBN 978-1-85065-551-0.

- Toynbee, Arnold (1987). A Study of History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505080-0.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003). The Ottoman Empire: 1326–1699. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-569-4.

- Tracy, James D. (2006). Europe's Reformations: 1450–1650. Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-3789-7.

- Walton, Mark W.; Nafziger, George. F.; Mbanda, Laurent W. (2003). Islam at War: A History. Praeger/Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-98101-0.

- Wheatcroft, Andrew (2009). The Enemy at the Gate: Habsburgs, Ottomans, and the Battle for Europe. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465013746.