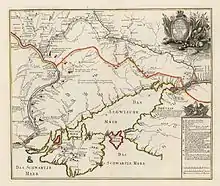

Russo-Turkish War (1735–1739)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1735–1739 between Russia and the Ottoman Empire was caused by the Ottoman Empire's war with Persia and continuing raids by the Crimean Tatars.[1] The war also represented Russia's continuing struggle for access to the Black Sea. In 1737, the Habsburg Monarchy joined the war on Russia's side, known in historiography as the Austro-Turkish War of 1737–1739.

| Russo-Turkish War of 1735–1739 Austro-Turkish War of 1737–1739 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Wallachian ruler: Constantin Mavrocordat Moldavian ruler: Grigore Ghica | |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Serbian Militia | |||||||||

Russian diplomacy before the war

By the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish war, Russia had managed to secure a favorable international situation by signing treaties with the Persian Empire in 1732–1735 (which was at war with Ottoman Empire in 1730–1735) and supporting the accession to the Polish throne of Augustus III in 1735 instead of the French protégé Stanislaw Leszczynski, nominated by pro-Turkish France. Austria had been Russia's ally since 1726.

The course of the war in 1735–1738

The casus belli were the raids of the Crimean Tatars on Cossack Hetmanate (Ukraine) in the end of 1735 and the Crimean khan's military campaign in the Caucasus. In 1736, the Russian commanders envisioned the seizure of Azov and the Crimea.

In 1735, on the eve of the war, the Russians made peace with Persia, giving back all the remaining territory conquered during the Russo-Persian War (Treaty of Ganja).[2]

On 20 May 1736, the Russian Dnieper Army (62,000 men) under the command of Field Marshal Burkhard Christoph von Münnich took by storm the Crimean fortifications at Perekop and occupied Bakhchysarai on June 17.[3] Crimean khans failed to defend their territory and repel the invasion, and in 1736, 1737 and 1738 Russian expeditionary armies broke through their defensive positions, pushing deep into the Crimean peninsula, driving the Tatar noblemen into the hills and forcing Khan Fet’ih Girey to take refuge at sea.[4] They burned Gozlev, Karasubazar, the khan's palace in the Crimean capital, Bakhchysarai, and captured the Ottoman fortress at Azov.[4] Khans Kaplan Girey and Fat’ih Girey were deposed by the Ottoman sultan for their incompetence.[4] However, 1737 to 1739 were notable plague years and all sides of the conflict were crippled by disease and unsanitary conditions.[5] Despite his success and a string of battlefield victories,[4] the outbreak of an epidemic coupled with short supplies[6] forced Münnich to retreat to Ukraine. On 19 June, the Russian Don Army (28,000 men) under the command of General Peter Lacy with the support from the Don Flotilla under the command of Vice Admiral Peter Bredahl seized the fortress of Azov.[3] In July 1737, Münnich's army took by storm the Turkish fortress of Ochakov. Lacy's army (already 40,000 men strong) marched into the Crimea the same month and captured Karasubazar. However, Lacy and his troops had to leave the Crimea due to lack of supplies. The Crimean campaign of 1736 ended in Russian withdrawal into Ukraine, after an estimated 30,000 losses, only 2,000 of which were lost to war-related causes and the rest to disease, hunger and famine.[7]

In July 1737, Austria entered the war against the Ottoman Empire, but was defeated a number of times, amongst others in the Battle of Banja Luka on 4 August 1737,[8] Battle of Grocka at 18, 21–22 July 1739,[9] and then lost Belgrade after an Ottoman siege from 18 July to September 1739. In August, Russia, Austria and Ottoman Empire began negotiations in Nemirov, which would turn out to be fruitless. There were no significant military operations in 1738. The Russian Army had to leave Ochakov and Kinburn due to the plague outbreak.

According to an Ottoman Muslim account of the war translated into English by C. Fraser, Bosnian Muslim women fought in battle since they "acquired the courage of heroes" against the Austrian Germans at the siege of Osterwitch-atyk (Östroviç-i âtık) fortress.[11] Women also fought in the defense of the fortresses of Būzin (Büzin) and Chetin (Çetin). Their bravery was described in a French account, too.[13] Yeni Pazar, Izvornik, Gradişka, and Banaluka were also struck by the Austrians.[14]

The final stage of the war

In 1739, the Russian army, commanded by Field Marshal Münnich, crossed the Dnieper, defeated the Turks at Stavuchany and occupied the fortress of Khotin (August 19) and Iaşi. However, Austria was defeated by the Turks at Grocka and signed a separate treaty in Belgrade with the Ottoman Empire on 21 August,[15] probably being alarmed at the prospect of Russian military success.[16] This, coupled with the imminent threat of a Swedish invasion,[17] and Ottoman alliances with Prussia, Poland and Sweden,[18] forced Russia to sign the Treaty of Niš with Turkey on 29 September, which ended the war.[19] The peace treaty granted Azov to Russia and consolidated Russia's control over the Zaporizhia.[20]

For Austria, the war proved a stunning defeat. The Russian forces were much more successful on the field, but they lost tens of thousands to disease.[21] The loss and desertion figures for the Ottomans are impossible to estimate.[5]

References

- Stone 2006, p. 64.

- Mikaberidze 2011, p. 329.

- Tucker 2010, p. 732.

- Davies L. B. The Russo-Turkish War, 1768–1774: Catherine II and the Ottoman Empire. 2016

- The Seven Years' War: Global Views. BRILL. 2012. P. 184

- Stone D. R. A Military History of Russia: From Ivan the Terrible to the War in Chechnya. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2006. P. 66

- Aksan 2007, p. 103.

- Ingrao, Samardžić & Pešalj 2011, p. 136-137.

- Ingrao, Samardžić & Pešalj 2011, p. 29.

- Oriental Translation Fund (1830). Publications. Royal Asiatic Society. pp. 17–.

- Michael Robert Hickok (1995). Looking for the Doctor's Son: Ottoman Administration of 18th Century Bosnia. University of Michigan. p. 34.

- Michael Robert Hickok (1997). Ottoman Military Administration in Eighteenth-Century Bosnia. BRILL. pp. 15–. ISBN 90-04-10689-8.

- Mikaberidze 2011, p. 210.

- Cook Ch., Broadhead Ph. The Routledge Companion to Early Modern Europe, 1453–1763. Routledge. 2006. P. 126

- Grinevetsky S., Zonn I., Zhiltsov S., Kosarev A., Kostianoy A. The Black Sea Encyclopedia. Springer. 2014. P. 661

- Somel S. Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire. Scarecrow Press. 2003. P. 169

- Mikaberidze 2011, p. 647.

- Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Volume 4. 1993. P. 476

- Black. J. European Warfare, 1660–1815. Routledge. 2002

Sources

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- Stone, David R. (2006). A Military History of Russia: From Ivan the Terrible to the War in Chechnya. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, Vol. II. ABC-CLIO.

- Ingrao, Charles; Samardžić, Nikola; Pešalj, Jovan, eds. (2011). The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557535948.

- Aksan, Virginia H. (2007). Ottoman Wars 1700–1870: An Empire Besieged. Routledge.

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas; Steinberg, Mark (2010). The History of Russia. Oxford University Press.