Sisodia

The Sisodia is an Indian Rajput clan, who claim Suryavanshi lineage. A dynasty belonging to this clan ruled over the kingdom of Mewar in Rajasthan. The name of the clan is also transliterated as Sesodia, Shishodia, Sishodia, Shishodya, Sisodya, Sisodia or Sisodiya.

Origins

The Sisodia dynasty traced its ancestry to Rahapa, a son of the 12th century Guhila king Ranasimha. The main branch of the Guhila dynasty ended with their defeat against the Khalji dynasty at the Siege of Chittorgarh (1303). In 1326, Rana Hammir who belonged to a cadet branch of that clan; however reclaimed control of the region, re-established the dynasty, and also became the propounder of the Sisodia dynasty clan, a branch of the Guhila dynasty, to which every succeeding Maharana of Mewar belonged, the Sisodias regain control of the former Guhila capital Chittor.[1][2][3]

Sisodias, like many other Rajput clans, claim origin from the legendary Suryavansha or solar dynasty.[4] Rajprashasti Mahakavyam, a 17th-century laudatory text commissioned by Mewar's ruler Rana Raj Singh, contains a partly mythical, partly legendary and partly historical genealogy of the Sisodias. The work was authored by Ranchhod Bhatt, a Telangana Brahmin whose family received regular gifts from the Sisodias. The genealogy traces the dynasty's origin to the rulers of Ayodhya, starting with Manu, who was succeeded by several emperors from the Ikshvaku dynasty, such as Rama. One ruler Vijaya left Ayodhya for "the south" as per a heavenly command (the exact place of his settlement is not mentioned). He was succeeded by 14 rulers whose names end in the suffix –aditya ("sun"). Grahaditya, the last of these, established a new dynasty called Grahaputra (that is, the Guhila dynasty). His eldest son Vashapa is said to have conquered Chitrakuta (modern Chittor) in the 8th century, and adopted the title Rawal, thanks to a boon from Shiva.[5] Third son of Raj Singh I, Rana Bahadur Singh embraced Islam and became a founder of "Ethaar" Dynasty. However, scholars suggest that the ancestor glorifying traditions of the Mughals was the reason behind the Sisodias claiming ancestry from an ancient dynasty mentioned in Ramayana.[6]

Grahaditya and Vashapa (better known as Bappa Rawal) are both popular figures in the Rajasthani folklore.[7] Their successors include people who are known to be historical figures. According to the Rajprashasti genealogy, one of these – Samar Singh – married Prithi, the sister of Prithviraj Chauhan. His grandson Rahapa adopted the title Rana (monarch). Rahapa's descendants spent some time at a place called Sisoda, and therefore, came to be known as "Sisodia".[5]

According to Persian text Maaser-al-Omra, the Sisodia Ranas of Udaipur originated from Noshizad, son of Noshirwan-i-Adil, the eldest daughter of Yazdegerd III.[8]

History

| Sisodia Rajputs of Mewar II (1326–1884) | |

|---|---|

| Hammir Singh | (1326–1364) |

| Kshetra Singh | (1364–1382) |

| Lakha Singh | (1382–1421) |

| Mokal Singh | (1421–1433) |

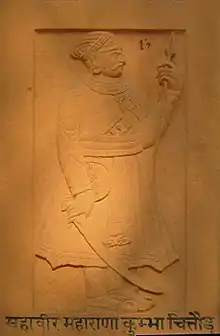

| Rana Kumbha | (1433–1468) |

| Udai Singh I | (1468–1473) |

| Rana Raimal | (1473–1508) |

| Rana Sanga | (1508–1527) |

| Ratan Singh II | (1528–1531) |

| Vikramaditya Singh | (1531–1536) |

| Vanvir Singh | (1536–1540) |

| Udai Singh II | (1540–1572) |

| Pratap Singh I | (1572–1597) |

| Amar Singh I | (1597–1620) |

| Karan Singh II | (1620–1628) |

| Jagat Singh I | (1628–1652) |

| Raj Singh I | (1652–1680) |

| Jai Singh | (1680–1698) |

| Amar Singh II | (1698–1710) |

| Sangram Singh II | (1710–1734) |

| Jagat Singh II | (1734–1751) |

| Pratap Singh II | (1751–1754) |

| Raj Singh II | (1754–1762) |

| Ari Singh II | (1762–1772) |

| Hamir Singh II | (1772–1778) |

| Bhim Singh | (1778–1828) |

| Jawan Singh | (1828–1838) |

| Sardar Singh | (1828–1842) |

| Swarup Singh | (1842–1861) |

| Shambhu Singh | (1861–1874) |

| Sajjan Singh | (1874–1884) |

| Fateh Singh | (1884–1930) |

| Bhupal Singh | (1930—1955) |

| Bhagwant Singh | (1955-1971) |

| Arvind Singh | (1971) |

The most notable Sisodia rulers were Rana Hamir (r. 1326-64), Rana Kumbha (r. 1433-68), Rana Sanga (r.1508–1528) and Rana Pratap (r. 1572-97). The Bhonsle clan, to which the Maratha empire's founder Shivaji belonged, also claimed descent from a branch of the royal Sisodia family.[9] Similarly, Rana dynasty of Nepal also claimed descent from Ranas of Mewar.[10]

According to the Sisodia chronicles, when the Delhi Sultan Alauddin Khalji attacked Chittorgarh in 1303, the Sisodia men performed saka (fighting to the death), while their women committed jauhar (self-immolation in preference to becoming enemy captives). This was repeated twice: when Bahadur Shah of Gujarat besieged Chittorgarh in 1535, and when the Mughal emperor Akbar conquered it in 1567.[11]

Frequent skirmishes with the Mughals greatly reduced the Sisodia power and the size of their kingdom. The Sisodias ultimately accepted the Mughal suzerainty, and some even fought in the Mughal army. However, the art and literary works commissioned by the subsequent Sisodia rulers emphasized their pre-Mughal past.[11] The Sisodias were the last Rajput dynasty to ally with the Mughals, and unlike other Rajput clans, never intermarried with the Mughal imperial family. Women from other Rajput clans that had marital relations with the Mughals were disallowed from marrying with the Sisodias.[12] The Sisodias cultivated an elite identity distinct from other Rajput clans through the poetic legends, eulogies and visual arts commissioned by them. James Tod, an officer of the British East India Company, relied on these works for his book Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, or the central and western Rajpoot states of India (1829-1832). His widely read work further helped spread the views of the Sisodias as a superior Rajput clan in colonial and post-colonial India.[11][13]

See also

References

- Rima Hooja (2006). A history of Rajasthan. Rupa. pp. 328–329. ISBN 9788129108906. OCLC 80362053.

- The Rajputs of Rajputana: a glimpse of medieval Rajasthan by M. S. Naravane ISBN 81-7648-118-1

- Manoshi, Bhattacharya. The Royal Rajputs. pp. 42–46. ISBN 9788129114013.

- Joanna Williams, Kaz Tsuruta, ed. (2007). Kingdom of the sun. Asian Art Museum - Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture. pp. 15–16. ISBN 9780939117390.

- Sri Ram Sharma (1971). Maharana Raj Singh and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 2–12. ISBN 9788120823983.

- Talbot, Cynthia (9 December 2015). The Last Hindu Emperor: Prithviraj Chauhan and the Indian Past, 1200–2000. ISBN 9781316432556.

- Dineschandra Sircar (1963). The Guhilas of Kiṣkindhā. Sanskrit College. p. 25.

- Wessly Lukose (2013). Contextual Missiology of the Spirit: Pentecostalism in Rajasthan, India. Wipf & Stock Publishers. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-62032-894-1.

- Singh K S (1998). India's communities. Oxford University Press. p. 2211. ISBN 978-0-19-563354-2.

- Greater Game: India's Race with Destiny and China by David Van Praagh

- Melia Belli Bose (2015). Royal Umbrellas of Stone. Brill. pp. 248–251. ISBN 9789004300569.

- Melia Belli Bose (2015). Royal Umbrellas of Stone. Brill. p. 37. ISBN 9789004300569.

- Freitag, Jason (2009). Serving empire, serving nation: James Tod and the Rajputs of Rajasthan. Leiden: Brill. pp. 3–5, 49. ISBN 978-90-04-17594-5. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

Further readings

- Gopinath Sharma (1954). Mewar & the Mughal Emperors (1526-1707 A.D.). S.L. Agarwala.