Slavery in Madras Presidency

Slavery in the Madras Presidency during the British Raj affected close to 20% of the population. The landlords were predominantly higher caste individuals. When those from the lower castes borrowed money against their land and defaulted, they entered a life of debt bondage. The slaves formed 12.2% of the total population in 1930.

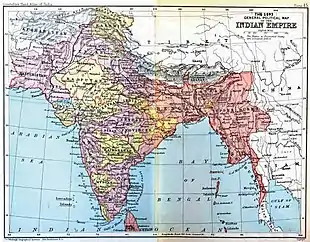

Imperial entities of India | |

| Dutch India | 1605–1825 |

|---|---|

| Danish India | 1620–1869 |

| French India | 1668–1954 |

| Casa da Índia | 1434–1833 |

| Portuguese East India Company | 1628–1633 |

| East India Company | 1612–1757 |

| Company rule in India | 1757–1858 |

| British Raj | 1858–1947 |

| British rule in Burma | 1824–1948 |

| Princely states | 1721–1949 |

| Partition of India | 1947 |

The patterns of slavery and slave population varied between districts. Various laws were passed during 1811, 1812 and 1823 to restrict slavery and prevent child labour, though the slave trade was only ended with the Indian Slavery Act of 1843, and the sale of slaves became a criminal offence in 1862 under the new Indian Penal Code.

Pattern

The Mirasdars, or landlords, were usually from the higher castes. Lower caste individuals borrowed money against their holdings from the mirasdars for marriage expenses, housing, or farming costs. On defaulting, they would find themselves obliged to repay the debt through labour. Hereditary relationships continued between debtors and their masters, as generations found themselves in debt bondage, leading to slavery. The opinion is divided on whether Brahmins directly used slaves or employed hired labourers. A theory, emitting from the note of the collector of Trichonopoly in 1819, states that the Brahmins employed lower castes labourers and the non-Brahmin landlords used lower caste slaves. Slavery was observed in almost all castes, both Brahmin and non-Brahmin.[1]

The pattern of slavery varied between different districts of the presidency, as did the sale of workers with land[2] In South Arcot and Coimbatore, slaves could be sold to anyone. In Coimbatore, slavery during the early 19th century was predominantly debt based. Serfs were sold along with land in Trichonopoly. The collector of Tinnevelly reported in 1919 that there was no specific pattern for selling serfs with land or slaves alone. It was later observed that slaves were sold with land, a situation closer to what would be called serfdom. A similar pattern was observed in Tanjore, where the sale of slaves to other estates was rare. In Madurai, slavery was in gradual decline as early as 1819. Some slaves, after liberation joined the Presidency army as Sepoys. In the northern parts of the Presidency, like Masulipatnam and Ganjam, agrarian slavery was minimal. In the Telugu speaking districts, the slaves were of three kinds – servants to zamindars, servants to Muslims, and labourers attached to land.

Distribution

The Law Commission report on slavery in 1841 contained the indicative figures on the number of slaves, based the numbers categorised as Pallars and Paraiyar.[3] In South Arcot , the number of slaves was 17,000 in 1819, comprising less than 4% of the population. In Tanjore, the numbers were reported to be more numerous, while in Madurai it was less. The Tinnelvely collector reported 38% of the whole population as slaves. In Trichonopoly, the collector estimated 10,000 slaves in wet parts and 600 in dry parts of the district. In Nellore, the slave population was 14.6% of the total population in 1827 and 16% in 1930. Slaves formed 12.2% of the total population in 1930.[4]

Laws

The Slave Trade Felony Act of 1811, created a criminal penalty for the importation of slaves into British Territory. There were proposed regulations in 1823 to prevent child labour.[5] In 1833, the Slavery Abolition Act received Royal Assent, though the Act did not "extend to any of the Territories in the Possession of the East India Company, or to the Island of Ceylon, or to the Island of Saint Helena."[6] Act V of 1843 finally ended the slave trade in India, and this was incorporated in 1862 under the new Indian Penal Code.[7]

See also

Notes

- British and Foreign Anti-slavery Society 1841, p. 5

- Kumar pp. 43–48

- British and Foreign Anti-slavery Society 1841, p. 4

- Kumar pp. 52–53

- British and Foreign Anti-slavery Society 1841, p. 27

- "3&4 Will. IV, cap. 73". www.pdavis.nl. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- Chatterjee, Indrani; Eaton, Richard Maxwell (2006). Slavery & South Asian History. Indiana University Press. p. 231. ISBN 0-253-34810-2.

Bibliography

- British and Foreign Anti-slavery Society (1841). Slavery and the slave trade in British India: with notices of the existence of these evils in the islands of Ceylon, Malacca, and Penang, drawn from official documents. T. Ward, and to be had at the office of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery society.

- Dharma, Kumar (1965). Land and Caste in South India: Agricultural Labor in the Madras Presidency During the Nineteenth Century. CUP Archive.