Slavery in India

Slavery was an established institution in ancient India by the start of the common era, or likely earlier.[1] However, its study in ancient times is problematic and contested because it depends on the translations of terms such as dasa and dasyu.[1][2]

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Slavery in India escalated during the Muslim domination of northern India after the 11th-century, after Muslim rulers re-introduced slavery to the Indian subcontinent.[1] It became a predominant social institution with the enslavement of Hindus, along with the use of slaves in armies for conquest, a long-standing practice within Muslim kingdoms at the time.[3][4] According to Muslim historians of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire era, after the invasions of Hindu kingdoms, Indians were taken as slaves, with many exported to Central Asia and West Asia.[5][6] Many slaves from the Horn of Africa were also imported into the Indian subcontinent to serve in the households of the powerful or the Muslim armies of the Deccan Sultanates and the Mughal Empire.[7][8][9]

Slavery in India continued through the 18th- and 19th-century. During colonial times Indians were taken into different parts of the world as slaves by the British East India Company,[9] and the British Empire.[10] Over a million indentured labourers also called girmitiyas from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar were taken as slave labourers to European colonies of British and Dutch in Fiji, South Africa, and Trinidad & Tobago.[11][12] The Portuguese imported African slaves into their Indian colonies on the Konkan coast between about 1530 and 1740.[13][14] Slavery was abolished in the possessions of the East India Company by the Indian Slavery Act, 1843.[15][16][17][18]

Slavery in Ancient India

The term dāsa and dāsyu in Vedic and other ancient Indian literature has been interpreted by as "servant" or "slave", but others have contested such meaning.[1][19] The term dāsa in the Rigveda, has been also been translated as an enemy, but overall the identity of this term remains unclear and disputed among scholars.[20] According to Scott Levi, if the term dasas is interpreted as slaves, then it was an established institution in ancient India by the start of the common era based on texts such as the Arthashastra, the Manusmriti[21] and the Mahabharata.[1] Slavery was "likely widespread by the lifetime of the Buddha" and it "likely existed in the Vedic period", states Levi, but adds that this association is problematic.[1]

Upinder Singh states that the Rig Veda is familiar with slavery, referring to enslavement in course of war or as a result of debt. She states that the use of dasa (Sanskrit: दास) and dasi in later times were used as terms for male and female slaves.[22] In contrast, Suvira Jaiswal states that dasa tribes were integrated in the lineage system of Vedic traditions, wherein dasi putras could rise to the status of priests, warriors and chiefs as shown by the examples of Kaksivant Ausija, Balbutha, Taruksa, Divodasa and others.[23] Some scholars contest the earlier interpretations of the term dasa as "slave", with or without "racial distinctions". According to Indologists Stephanie W. Jamison and Joel P. Brereton, known for their recent translation of the Rigveda, the dasa and dasyu are human and non-human beings who are enemies of Arya.[24] These according to the Rigveda, state Jamison and Brereton, are destroyed by the Vedic deity Indra.[24] The interpretation of "dasas as slaves" in the Vedic era is contradicted by hymns such as 2.12 and 8.46 that describe "wealthy dasas" who charitably give away their wealth. Similarly, state Jamison and Brereton, the "racial distinctions" are not justified by the evidence.[24] According to the Indologist Thomas Trautmann, the relationship between the Arya and Dasa appears only in two verses of the Rigveda, is vague and unexpected since the Dasa were "in some ways more economically advanced" than the Arya according to the textual evidence.[25]

According to Asko Parpola, the term dasa in ancient Indian texts has proto-Saka roots, where dasa or daha simply means "man".[26] Both "dasa" and "dasyu" are uncommon in Indo-Iranian languages (including Sanskrit and Pali), and these words may be a legacy of the PIE root "*dens-", and the word "saka" may have evolved from "dasa", states Parpola.[26] According to Micheline Ishay – a professor of human rights studies and sociology, the term "dasa" can be "translated as slave". The institution represented unfree labor with fewer rights, but "the supposed slavery in [ancient] India was of mild character and limited extent" like Babylonian and Hebrew slavery, in contrast to the Hellenic world.[27] The "unfree labor" could be of two types in ancient India: the underadsatva and the ahitaka, states Ishay.[27] A person in distress could pledge themselves for work leading to underadsatava, while under ahitaka a person's "unfree labor" was pledged or mortgaged against a debt or ransom when captured during a war.[27] These forms of slavery limited the duration of "unfree labor" and such a slave had rights to their property and could pass their property to their kin, states Ishay.[27]

The term dasa appears in early Buddhist texts, a term scholars variously interpret as servant or slave.[28] Buddhist manuscripts also mention kapyari, which scholars have translated as a legally bonded servant (slave).[29] According to Gregory Schopen, in the Mahaviharin Vinaya, the Buddha says that a community of monks may accept dasa for repairs and other routine chores. Later, the same Buddhist text states that the Buddha approved the use of kalpikara and the kapyari for labor in the monasteries and approved building separate quarters for them.[30] Schopen interprets the term dasa as servants, while he interprets the kalpikara and kapyari as bondmen and slave respectively because they can be owned and given by laity to the Buddhist monastic community.[30] According to Schopen, since these passages are not found in Indian versions of the manuscripts, but found in a Sri Lankan version, these sections may have been later interpolations that reflect a Sri Lankan tradition, rather than early Indian.[30] The discussion of servants and bonded labor is also found in manuscripts found in Tibet, though the details vary.[30][31]

The discussion of servant, bonded labor and slaves, states Scopen, differs significantly in different manuscripts discovered for the same Buddhist text in India, Nepal and Tibet, whether they are in Sanskrit or Pali language.[31] These Buddhist manuscripts present a set of questions to ask a person who wants to become a monk or nun. These questions inquire if the person is a dasa and dasi, but also ask additional questions such as "are you ahrtaka" and "are you vikritaka". The later questions have been interpreted in two ways. As "are you one who has been seized" (ahrtaka) and "are you one who has been sold" (vikritaka) respectively, these terms are interpreted as slaves.[31] Alternatively, they have also been interpreted as "are you doubtless" and "are you blameworthy" respectively, which does not mean slave.[31] Further, according to these texts, Buddhist monasteries refused all servants, bonded labor and slaves an opportunity to become a monk or nun, but accepted them as workers to serve the monastery.[31][30]

The Indian texts discuss dasa and bonded labor along with their rights, as well as a monastic community's obligations to feed, clothe and provide medical aid to them in exchange for their work. This description of rights and duties in Buddhist Vinaya texts, says Schopen, parallel those found in Hindu Dharmasutra and Dharmasastra texts.[32] The Buddhist attitude to servitude or slavery as reflected in Buddhist texts, states Schopen, may reflect a "passive acceptance" of cultural norms of the Brahmanical society midst them, or more "justifiably an active support" of these institutions.[33] The Buddhist texts offer "no hint of protest or reform" to such institutions, according to Schopen.[33]

Kautilya's Arthashastra dedicates the thirteenth chapter on dasas, in his third book on law. This Sanskrit document from the Maurya Empire period (4th century BCE) has been translated by several authors, each in a different manner. Shamasastry's translation of 1915 maps dasa as slave, while Kangle leaves the words as dasa and karmakara. According to Kangle's interpretation, the verse 13.65.3–4 of Arthasastra forbids any slavery of "an Arya in any circumstances whatsoever", but allows the Mlecchas to "sell an offspring or keep it as pledge".[34] Patrick Olivelle agrees with this interpretation. He adds that an Arya or Arya family could pledge itself during times of distress into bondage, and these bonded individuals could be converted to slave if they committed a crime thereby differing with Kangle's interpretation.[35] According to Kangle, the Arthasastra forbids enslavement of minors and Arya from all four varnas and this inclusion of Shudras stands different from the Vedic literature.[36] Kangle suggests that the context and rights granted to dasa by Kautilya implies that the word had a different meaning than the modern word slave, as well as the meaning of the word slave in Greek or other ancient and medieval civilizations.[37] According to Arthashastra, anyone who had been found guilty of nishpatitah (Sanskrit: निष्पातित, ruined, bankrupt, a minor crime)[38] may mortgage oneself to become dasa for someone willing to pay his or her bail and employ the dasa for money and privileges.[37][39]

The term dasa in Indic literature when used as a suffix to a bhagavan (deity) name, refers to a pious devotee.[40][41]

Slavery in Medieval India

Slavery escalated during the medieval era in India with the arrival of Islam.[1][4] Wink summarizes the period as follows,

Slavery and empire-formation tied in particularly well with iqta and it is within this context of Islamic expansion that elite slavery was later commonly found. It became the predominant system in North India in the thirteenth century and retained considerable importance in the fourteenth century. Slavery was still vigorous in fifteenth-century Bengal, while after that date it shifted to the Deccan where it persisted until the seventeenth century. It remained present to a minor extent in the Mughal provinces throughout the seventeenth century and had a notable revival under the Afghans in North India again in the eighteenth century.

— Al Hind, André Wink[42]

Slavery as a predominant social institution emerged from the 8th century onwards in India, particularly after the 11th century, as part of systematic plunder and enslavement of infidels, along with the use of slaves in armies for conquest.[3]

But unlike other parts of the medieval Muslim world, slavery was not widespread in Kashmir. Except for the Sultans, there is no evidence the elite kept slaves. The Kashmiris despised slavery. Concubinage was also not practised.[43]

Islamic invasions (8th to 12th century AD)

Andre Wink summarizes the slavery in 8th and 9th century India as follows,

(During the invasion of Muhammad al-Qasim), invariably numerous women and children were enslaved. The sources insist that now, in dutiful conformity to religious law, 'the one-fifth of the slaves and spoils' were set apart for the caliph's treasury and despatched to Iraq and Syria. The remainder was scattered among the army of Islam. At Rūr, a random 60,000 captives reduced to slavery. At Brahamanabad 30,000 slaves were allegedly taken. At Multan 6,000. Slave raids continued to be made throughout the late Umayyad period in Sindh, but also much further into Hind, as far as Ujjain and Malwa. The Abbasid governors raided Punjab, where many prisoners and slaves were taken.

— Al Hind, André Wink[44]

Levi notes that these figures cannot be entirely dismissed as exaggerations since they appear to be supported by the reports of contemporary observers. In the early 11th century Tarikh al-Yamini, the Arab historian Al-Utbi recorded that in 1001 the armies of Mahmud of Ghazni conquered Peshawar and Waihand (capital of Gandhara) after Battle of Peshawar (1001), "in the midst of the land of Hindustan", and enslaved thousands.[45][46] Later, following his twelfth expedition into India in 1018–19, Mahmud is reported to have returned to with such a large number of slaves that their value was reduced to only two to ten dirhams each. This unusually low price made, according to Al-Utbi, "merchants came from distant cities to purchase them, so that the countries of Central Asia, Iraq and Khurasan were swelled with them, and the fair and the dark, the rich and the poor, mingled in one common slavery".

Delhi Sultanate (12th to 16th century AD)

During the Delhi Sultanate period (1206–1555), references to the abundant availability of low-priced Indian slaves abound.[1] Many of these Indian slaves were used by Muslim nobility in the subcontinent, but others were exported to satisfy the demand in international markets. Some slaves converted to Islam to receive protection. Children fathered by Muslim masters on non-Muslim slaves would be raised Muslim. Non-Muslim women, who Muslim soldiers and elites had slept with, would convert to Islam to avoid rejection by their own communities.[47] Scott Levi states that "Movement of considerable numbers of Hindus to the Central Asian slave markets was largely a product of the state building efforts of the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire in South Asia".[48]

The revenue system of the Delhi Sultanate produced a considerable proportion of the Indian slave population as these rulers, and their subordinate shiqadars, ordered their armies to abduct large numbers of locals as a means of extracting revenue.[49][50] While those communities that were loyal to the Sultan and regularly paid their taxes were often excused from this practice, taxes were commonly extracted from other, less loyal groups in the form of slaves. Thus, according to Barani, the Shamsi "slave-king" Balban (r. 1266–87) ordered his shiqadars in Awadh to enslave those peoples resistant to his authority, implying those who refused to supply him with tax revenue.[51] Sultan Alauddin Khalji (r. 1296–1316) is similarly reported to have legalised the enslavement of those who defaulted on their revenue payments.[51] This policy continued during the Mughal era.[52][53][54][55][56]

An even greater number of people were enslaved as a part of the efforts of the Delhi Sultans to finance their expansion into new territories.[57] For example, while he himself was still a military slave of the Ghurid Sultan Muizz u-Din, Qutb-ud-din Aybak (r. 1206–10 as the first of the Shamsi slave-kings) invaded Gujarat in 1197 and placed some 20,000 people in bondage. Roughly six years later, he enslaved an additional 50,000 people during his conquest of Kalinjar. Later in the 13th century, Balban's campaign in Ranthambore, reportedly defeated the Indian army and yielded "captives beyond computation".[56][58]

Levi states that the forcible enslavement of non-Muslims during Delhi Sultanate was motivated by the desire for war booty and military expansion. This gained momentum under the Khalji and Tughluq dynasties, as being supported by available figures.[1][56] Zia uddin Barani suggested that Sultan Alauddin Khalji owned 50,000 slave-boys, in addition to 70,000 construction slaves. Sultan Firuz Shah Tughluq is said to have owned 180,000 slaves, roughly 12,000 of whom were skilled artisans.[49][56][59][60][55][61] A significant proportion of slaves owned by the Sultans were likely to have been military slaves and not labourers or domestics. However earlier traditions of maintaining a mixed army comprising both Indian soldiers and Turkic slave-soldiers (ghilman, mamluks) from Central Asia, were disrupted by the rise of the Mongol Empire reducing the inflow of mamluks. This intensified demands by the Delhi Sultans on local Indian populations to satisfy their need for both military and domestic slaves. The Khaljis even sold thousands of captured Mongol soldiers within India.[50][59][62] China, Turkistan, Persia, and Khurusan were sources of male and female slaves sold to Tughluq India.[63][64][65][66] The Yuan Dynasty Emperor in China sent 100 slaves of both sexes to the Tughluq Sultan, and he replied by also sending the same number of slaves of both sexes.[67]

Mughal Empire (16th to 19th century)

The slave trade continued to exist in the Mughal Empire, however it was greatly reduced in scope, primarily limited to domestic servitude and debt bondage, and deemed "mild" and incomparable to the Arab slave trade or transatlantic slave trade.[68][69]

One Dutch merchant in the 17th century writes about Abd Allah Khan Firuz Jang, an Uzbek noble at the Mughal court during the 1620s and 1630s, who was appointed to the position of governor of the regions of Kalpi and Kher and, in the process of subjugating the local rebels, beheaded the leaders and enslaved their women, daughters and children, who were more than 200,000 in number.[70]

When Shah Shuja was appointed as governor of Kabul, he carried out a war in Indian territory beyond the Indus. Most of the women burnt themselves to death to save their honour. Those captured were "distributed" among Muslim mansabdars.[52][71][72][73] The Augustinian missionary Fray Sebastian Manrique, who was in Bengal in 1629–30 and again in 1640, remarked on the ability of the shiqdār—a Mughal officer responsible for executive matters in the pargana, the smallest territorial unit of imperial administration to collect the revenue demand, by force if necessary, and even to enslave peasants should they default in their payments.[71]

A survey of a relatively small, restricted sample of seventy-seven letters regarding the manumission or sale of slaves in the Majmua-i-wathaiq reveals that slaves of Indian origin (Hindi al-asal) accounted for over fifty-eight percent of those slaves whose region of origin is mentioned. The Khutut-i-mamhura bemahr-i qadat-i Bukhara, a smaller collection of judicial documents from early-eighteenth-century Bukhara, includes several letters of manumission, with over half of these letters referring to slaves "of Indian origin". Even in the model of a legal letter of manumission written by the chief qazi for his assistant to follow, the example used is of a slave "of Indian origin".[74]

The export of slaves from India was limited to debt defaulters and rebels against the Mughal Empire. The Ghakkars of Punjab acted as intermediaries for such slave for trade to Central Asian buyers.[69]

Fatawa-i Alamgiri

The Fatawa-e-Alamgiri (also known as the Fatawa-i-Hindiya and Fatawa-i Hindiyya) was sponsored by Aurangzeb in the late 17th century.[75] It compiled the law for the Mughal Empire, and involved years of effort by 500 Muslim scholars from South Asia, Iraq and Saudi Arabia. The thirty volumes on Hanafi-based sharia law for the Empire was influential during and after Auruangzeb's rule, and it included many chapters and laws on slavery and slaves in India.[76][77][78]

Some of the slavery-related law included in Fatawa-i Alamgiri were,

- the right of Muslims to purchase and own slaves,[77]

- a Muslim man's right to have sex with a captive slave girl he owns or a slave girl owned by another Muslim (with master's consent) without marrying her,[79]

- no inheritance rights for slaves,[80]

- the testimony of all slaves was inadmissible in a court of law[81]

- slaves require permission of the master before they can marry,[82]

- an unmarried Muslim may marry a slave girl he owns but a Muslim married to a Muslim woman may not marry a slave girl,[83]

- conditions under which the slaves may be emancipated partially or fully.[78]

Export of Indian slaves to international markets

Alongside Buddhist Oirats, Christian Russians, Afghans, and the predominantly Shia Iranians, Indian slaves were an important component of the highly active slave markets of medieval and early modern Central Asia. The all pervasive nature of slavery in this period in Central Asia is shown by the 17th century records of one Juybari Sheikh, a Naqshbandi Sufi leader, owning over 500 slaves, forty of whom were specialists in pottery production while the others were engaged in agricultural work.[84] High demand for skilled slaves, and India's larger and more advanced textile industry, agricultural production and tradition of architecture demonstrated to its neighbours that skilled-labour was abundant in the subcontinent leading to enslavement and export of large numbers of skilled labour as slaves, following their successful invasions.[85]

After sacking Delhi, Timur enslaved several thousand skilled artisans, presenting many of these slaves to his subordinate elite, although reserving the masons for use in the construction of the Bibi-Khanym Mosque in Samarkand.[86] Young female slaves fetched higher market price than skilled construction slaves, sometimes by 150%.[87]

Under early European colonial powers

According to one author, in spite of the best efforts of the slave-holding elite to conceal the continuation of the institution from the historical record, slavery was practised throughout colonial India in various manifestations.[88] In reality, the movement of Indians to the Bukharan slave markets did not cease and Indian slaves continued to be sold in the markets of Bukhara well into the nineteenth century.

17th century

Slavery existed in Portuguese India after the 16th century. "Most of the Portuguese," says Albert. D. Mandelslo, a German itinerant writer, "have many slaves of both sexes, whom they employ not only on and about their persons, but also upon the business they are capable of, for what they get comes with the master."

The Dutch, too, largely dealt in slaves. They were mainly Abyssian, known in India as Habshis or Sheedes. The curious mixed race in Kanara on the West coast has traces of these slaves.[89]

The Dutch Indian Ocean slave trade was primarily mediated by the Dutch East India Company, drawing captive labour from three commercially closely linked regions: the western, or Southeast Africa, Madagascar, and the Mascarene Islands (Mauritius and Reunion); the middle, or Indian subcontinent (Malabar, Coromandel, and the Bengal/Arakan coast); and the eastern, or Malaysia, Indonesia, New Guinea (Irian Jaya), and the southern Philippines.

The Dutch traded slaves from fragmented or weak small states and stateless societies in the East beyond the sphere of Islamic influence, to the company's Asian headquarters, the "Chinese colonial city" of Batavia (Jakarta), and its regional centre in coastal Sri Lanka. Other destinations included the important markets of Malacca (Melaka) and Makassar (Ujungpandang), along with the plantation economies of eastern Indonesia (Maluku, Ambon, and Banda Islands), and the agricultural estates of the southwestern Cape Colony (South Africa).

On the Indian subcontinent, Arakan/Bengal, Malabar, and Coromandel remained the most important source of forced labour until the 1660s. Between 1626 and 1662, the Dutch exported on an average 150–400 slaves annually from the Arakan-Bengal coast. During the first thirty years of Batavia's existence, Indian and Arakanese slaves provided the main labour force of the company's Asian headquarters. Of the 211 manumitted slaves in Batavia between 1646 and 1649, 126 (59.71%) came from South Asia, including 86 (40.76%) from Bengal. Slave raids into the Bengal estuaries were conducted by joint forces of Magh pirates, and Portuguese traders (chatins) operating from Chittagong outside the jurisdiction and patronage of the Estado da India, using armed vessels (galias). These raids occurred with the active connivance of the Taung-ngu (Toungoo) rulers of Arakan. The eastward expansion of the Mughal Empire, however, completed with the conquest of Chittagong in 1666, cut off the traditional supplies from Arakan and Bengal. Until the Dutch seizure of the Portuguese settlements on the Malabar coast (1658–63), large numbers of slaves were also captured and sent from India's west coast to Batavia, Ceylon, and elsewhere. After 1663, however, the stream of forced labour from Cochin dried up to a trickle of about 50–100 and 80–120 slaves per year to Batavia and Ceylon, respectively.

In contrast with other areas of the Indian subcontinent, Coromandel remained the centre of a sporadic slave trade throughout the seventeenth century. In various short-lived expansions accompanying natural and human-induced calamities, the Dutch exported thousands of slaves from the east coast of India. A prolonged period of drought followed by famine conditions in 1618–20 saw the first large-scale export of slaves from the Coromandel coast in the seventeenth century. Between 1622 and 1623, 1,900 slaves were shipped from central Coromandel ports, like Pulicat and Devanampattinam. Company officials on the coast declared that 2,000 more could have been bought if only they had the funds.

The second expansion in the export of Coromandel slaves occurred during a famine following the revolt of the Nayaka Indian rulers of South India (Tanjavur, Senji, and Madurai) against Bijapur overlordship (1645) and the subsequent devastation of the Tanjavur countryside by the Bijapur army. Reportedly, more than 150,000 people were taken by the invading Deccani Muslim armies to Bijapur and Golconda. In 1646, 2,118 slaves were exported to Batavia, the overwhelming majority from southern Coromandel. Some slaves were also acquired further south at Tondi, Adirampatnam, and Kayalpatnam.

A third phase in slaving took place between 1659 and 1661 from Tanjavur as a result of a series of successive Bijapuri raids. At Nagapatnam, Pulicat, and elsewhere, the company purchased 8,000–10,000 slaves, the bulk of whom were sent to Ceylon while a small portion were exported to Batavia and Malacca. A fourth phase (1673–77) started from a long drought in Madurai and southern Coromandel starting in 1673, and intensified by the prolonged Madurai-Maratha struggle over Tanjavur and punitive fiscal practices. Between 1673 and 1677, 1,839 slaves were exported from the Madurai coast alone. A fifth phase occurred in 1688, caused by poor harvests and the Mughal advance into the Karnatak. Thousands of people from Tanjavur, mostly girls and little boys, were sold into slavery and exported by Asian traders from Nagapattinam to Aceh, Johor, and other slave markets. In September 1687, 665 slaves were exported by the English from Fort St. George, Madras. Finally, in 1694–96, when warfare once more ravaged South India, a total of 3,859 slaves were imported from Coromandel by private individuals into Ceylon.[90] [91] [92][93]

The volume of the total Dutch Indian Ocean slave trade has been estimated to be about 15–30% of the Atlantic slave trade, slightly smaller than the trans-Saharan slave trade, and one-and-a-half to three times the size of the Swahili and Red Sea coast and the Dutch West India Company slave trades.[94]

18th to 20th century

.jpg.webp)

Between 1772 and 1833, the British parliament debates, as recorded in Hansard confirm the existence of extensive slavery in India.[95] A slave market is noted as operating in Calcutta, and the Company Court House permitted slave ownership to be registered, for a fee of Rs. 4.25 or Rs.4 and 4 annas.[96]

A number of abolitionist missionaries, including Rev. James Peggs, Rev. Howard Malcom, Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, and William Adams offered commentaries on the Parliamentary debates, and added their own estimates of the numbers effected by, and forms of slavery in South Asia, by region and caste, in the 1830s. In a series of publications that included their: "India’s Cries to British Humanity, Relative to Infanticide, British Connection with Idolatry, Ghau Murders, Suttee, Slavery, and Colonization in India", "Slavery and the slave trade in British India; with notices of the existence of these evils in the islands of Ceylon, Malacca, and Penang, drawn from official documents", and "The Law and Custom of Slavery in British India: In a Series of Letters to Thomas Fowell Buxton, Esq" tables were published detailing the estimates.

| Province or Kingdom | Est. Slaves | |

|---|---|---|

| Malabar | 147,000 | |

| Malabar and Wynad (Wayanad) | 100,000 | |

| Canara, Coorg, Wynad, Cochin, and Travancore | 254,000 | |

| Tinnevelly (Tirunelveli) | 324,000 | |

| Trichinopoly | 10,600 | |

| Arcot | 20,000 | |

| Canara | 80,000 | |

| Assam | 11,300 | |

| Surat | 3,000 | |

| Ceylon (Sri Lanka) | 27,397 | |

| Penang | 3,000 | |

| Sylhet and Buckergunge (Bakerganj) | 80,000 | |

| Behar | 22,722 | |

| Tizhoot | 11,061 | |

| Southern Mahratta Country | 7,500 | |

| Sub Total | 1,121,585 |

The publications suggest slavery was endemic, with individual published letters, or reports discussing the practice in a small geographic areas often mentioning thousand of slaves, e.g.

Slavery in Bombay. In Mr. Chaplin's report, made in answer to queries addressed to the collectors of districts, he says, "Slavery in the Deccan is very prevalent and we know that it has been recognized by the Hindu law, and by the custom of the country, from time immemorial'." Mr. Baber gives more definite information of the number of slaves in one of the divisions of the Bombay territory, viz., that " lying between the rivers Kistna and Toongbutra," the slaves in which he estimates at 15,000 ; and in the southern Mahratta country, he observes, " All the Jagheerdars, Deshwars, Zemindars, principal Brahmins, and Sahookdars, retain slaves in their domestic establishments ; in fact, in every Mahratta household of consequence, they are, both male and female, especially the latter, to be found, and indeed are considered to be indispensable."

— Par. Pap. No. 128, 1834, p. 4.

While Andrea Major, in Slavery, Abolitionism and Empire in India, 1772–1843, published in 2014:

In fact, eighteenth century Europeans, including some Britons, were involved in buying, selling and exporting Indian slaves, transferring them around the subcontinent or to European slave colonies across the globe. Moreover, many eighteenth century European households in India included domestic slaves, with the owners' right of property over them being upheld in law. Thus, although both colonial observers and subsequent historians usually represent South Asian slavery as an indigenous institution, with which the British were only concenred as colonial reforms, until the end of the eighteenth century Europeans were deeply implicated in both slave-holding and slave-trading in the region.

Regulation and prohibition

In Bengal the East India Company, in 1773, opted to codify the pre-existing pluralistic judicial system, with Europeans subject to English Common law, Muslims to the sharia based Fatawa-e-Alamgiri, and Hindus to an adaptation of a Dharmaśāstra named Manusmriti, that became known as the Hindu law,[101] with the applicable legal traditions, and for Hindus an interpretation of verse 8.415 of the Manusmriti,[21] regulating the practice of slavery.[97] The Company later passed regulations 9, and 10 of 1774, prohibiting the trade in slaves without written deed, and the sale of anyone not already enslaved.,[100] and reissued the legislation in 1789, after a Danish Captain, Peter Horrebow, was caught, prosecuted, fined, and jailed for attempting to smuggle 150 Bengali slaves to Ceylon.[100] The Company subsequently issued regulations 10 of 1811, prohibiting the transport of slaves into Company territory.[100]

When the United Kingdom abolished slavery in its overseas territories, through the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, it excluded the non Crown territories administered by the East India Company from the scope of the statute.[102]

The Indian Slavery Act of 1843 prohibit Company employees from owning, or dealing, along with granting limited protection under the law, that included the ability for a slave to own, transfer or inherit property, notionally benefitting the millions held in Company territory, that in an 1883 article on Slavery in India and Egypt, Sir Henry Bartle Frere (who sat on the Viceroy's Council 1859-67), estimated that within the Companies territory, that did not yet extend to half the sub-continent, at the time of the act:

Comparing such information, district by district, with the very imperfect estimates of the total population fifty years ago, the lowest estimate I have been able to form of the total slave population of British India, in 1841, is between eight and nine millions of souls. The slaves set free in the British colonies on the 1st of August, 1834, were estimated at between 800,000 and 1,000,000; and the slaves in North and South America, in 1860, were estimated at 4,000,000. So that the number of human beings whose liberties and fortunes, as slaves and owners of slaves, were at stake when the emancipation of the slaves was contemplated in British India, far exceeded the number of the same classes in all the slaveholding colonies and dominions of Great Britain and America put together.

— Fortnightly Review, 1883, p. 355[103]

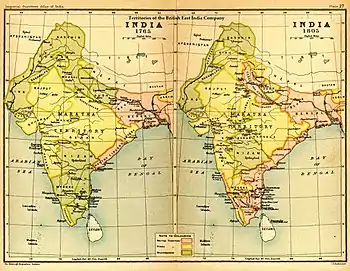

Growth of East India Company controlled territories (pink) between 1765, 1805, 1837 and 1857

Growth of East India Company controlled territories (pink) between 1765, 1805, 1837 and 1857

Portugal gradually prohibited the importation of slaves into Portuguese India, following the 1818 Anglo-Portuguese anti slavery treaty, a subsequent 1836 Royal Edict, and a second Anglo-Portuguese treaty in 1842 reduced the external trade, but the institution itself was only prohibited in 1876.[104]

France prohibited slavery, in French India, via the Proclamation of the Abolition of Slavery in the French Colonies, 27 April 1848.[105]

- British Indian Empire

Provisions of the Indian Penal Code of 1861 effectively abolished slavery in British India by making the enslavement of human beings a criminal offense.[15][16][106][18] Criminalisation of the institution was required of the princely states, with the likes of the 1861 Anglo-Sikkimese treaty requiring Sikkim to outlaw the institution.[96]

Officials that inadvertently used the term "slave" would be reprimanded, but the actual practices of servitude continued unchanged. Scholar Indrani Chatterjee has termed this "abolition by denial."[107] In the rare cases when the anti-slavery legislation was enforced, it addressed the relatively smaller practices of export and import of slaves, but it did little to address the agricultural slavery that was pervasive inland. The officials in the Madras Presidency turned a blind eye to agricultural slavery claiming that it was a benign form of bondage that was in fact preferable to free labour.[108]

Indentured labor system

After the United Kingdom prohibited slavery by the mid 19th century, it introduced a new indentured labor system that scholars suggest was slavery by contract.[109][110][111] According to Richard Sheridan, quoting Dookhan, "[the plantation owners] continued to apply or sanction the means of coercion common to slavery, and in this regard the Indians fared no better than the ex-slaves".[112]

In this new system, they were called indentured labourers. South Asians began to replace Africans previously brought as slaves, under this indentured labour scheme to serve on plantations and mining operations across the British empire.[113] The first ships carrying indentured labourers left India in 1836.[113] In the second half of the 19th century, indentured Indians were treated as inhumanely as the enslaved people previously had been. They were confined to their estates and paid a pitiful salary. Any breach of contract brought automatic criminal penalties and imprisonment.[113] Many of these were brought away from their homelands deceptively. Many from inland regions over a thousand kilometers from seaports were promised jobs, were not told the work they were being hired for, or that they would leave their homeland and communities. They were hustled aboard the waiting ships, unprepared for the long and arduous four-month sea journey. Charles Anderson, a special magistrate investigating these sugarcane plantations, wrote to the British Colonial Secretary declaring that with few exceptions, the indentured labourers are treated with great and unjust severity; plantation owners enforced work in plantations, mining and domestic work so harshly, that the decaying remains of immigrants were frequently discovered in fields. If labourers protested and refused to work, they were not paid or fed: they simply starved.[113][114]

Contemporary slavery

According to a Walk Free Foundation report in 2018, there were 46 million people enslaved worldwide in 2016, and there were 8 million people in India were living in the forms of modern slavery, such as bonded labour, child labour, forced marriage, human trafficking, forced begging, among others,[115] compared to 18.3 million in 2016.[116][117][118][119][120]

The existence of slavery, especially child slavery, in South Asia and the world has been alleged by NGOs and the media.[121][122] With the Bonded Labour (Prohibition) Act 1976 and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (concerning slavery and servitude), a spotlight has been placed on these problems in the country. One of the areas identified as problematic were granite quarries.[123][124]

See also

- Veth (India), a system of forced labour

- History of slavery in Asia

- Child labour in India

- Labour in India

References

- Scott C. Levi (2002). "Hindus Beyond the Hindu Kush: Indians in the Central Asian Slave Trade". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press. 12 (3): 277–288. doi:10.1017/S1356186302000329. JSTOR 25188289., Quote: "Sources such as the Arthasastra, the Manusmriti and the Mahabharata demonstrate that institutionalized slavery was well established in India by beginning of the common era. Earlier sources suggest that it was likely to have been equally widespread by the lifetime of the Buddha (sixth century BC), and perhaps even as far back as the Vedic period. [footnote 2: (...) While it is likely that the institution of slavery existed in India during the Vedic period, the association of the Vedic 'Dasa' with 'slaves' is problematic and likely to have been a later development."

- Ram Sharan Sharma (1990). Śūdras in Ancient India: A Social History of the Lower Order Down to Circa A.D. 600. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-81-208-0706-8.

- Andre Wink (1991), Al-Hind: the Making of the Indo-Islamic World, vol. 1, Brill Academic (Leiden), ISBN 978-9004095090, pages 14-32, 172-207

-

- Burjor Avari (2013), Islamic Civilization in South Asia, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415580618, pages 41-68;

- Abraham Eraly (2014), The Age of Wrath: A History of the Delhi Sultanate, Part VIII, Chapter 2, Penguin, ISBN 978-0670087181;

- Vincent A. Smith, The early history of India, 3rd Edition, Oxford University Press, Reprinted in 1999 by Atlantic Publishers, Books IV and V - Muhammadan Period;

- K. S. Lal, Muslim Slave System in Medieval India (New Delhi, 1994);

- Salim Kidwai, "Sultans, Eunuchs and Domestics: New Forms of Bondage in Medieval India", in Utsa Patnaik and Manjari Dingwaney (eds), Chains of Servitude: bondage and slavery in India (Madras, 1985).

- Utsa Patnaik and Manjari Dingwaney (eds), Chains of Servitude: bondage and slavery in India (Madras, 1985)

- Scott C. Levi (2002). "Hindus Beyond the Hindu Kush: Indians in the Central Asian Slave Trade". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press. 12 (3): 278–288. JSTOR 25188289.

- Bernard Lewis (1992). Race and Slavery in the Middle East: An Historical Enquiry. Oxford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-19-505326-5.

- Indrani Chatterjee; Richard M. Eaton (2006). Slavery and South Asian History. Indiana University Press. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-0-253-11671-0., Quote: "The importation of Ethiopian slaves into the western Deccan profoundly altered the region's society and culture [...]"

- [a] Andrea Major (2012). Slavery, Abolitionism and Empire in India, 1772-1843. Liverpool University Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-1-78138-903-4.;

[b]David Eltis; Stanley L. Engerman (2011). The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420–AD 1804. Cambridge University Press. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-1-316-18435-6., Quote: "The war was considered a major reason for the importation of Ethiopian slaves into India during the sixteen century. Africans of slave origins played a major role in the politics of Mughal India [...]" - William Gervase Clarence-Smith (2013). The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century. Routledge. pp. 4–5, 64–66 with footnotes on 69. ISBN 978-1-135-18214-4.

- Andrea Major (2014), Slavery, Abolitionism and Empire in India, 1772-1843, Liverpool University Press, ISBN 9781781381113, p. 43

- Ghoshal, Devjyot. "The forgotten story of India's colonial slave workers who began leaving home 180 years ago". Quartz India. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- William, Eric (1942). History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago. Buffalo: Effworld Inc. pp. 1–4. ISBN 9781617590108.

- Carole Elizabeth Boyce Davies (2008). Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture [3 volumes]: Origins, Experiences, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 553–556. ISBN 978-1-85109-705-0.

- Walker, Timothy (2004). "Abolishing the slave trade in Portuguese India: documentary evidence of popular and official resistance to crown policy, 1842–60". Slavery & Abolition. Taylor & Francis. 25 (2): 63–79. doi:10.1080/0144039042000293045. S2CID 142692153.

- "Slavery :: Britannica Concise Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- "Historical survey > Slave-owning societies". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Islamic Law and the Colonial Encounter in British India Archived 29 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Levi, Scott C. (1 November 2002). "Hindus Beyond the Hindu Kush: Indians in the Central Asian Slave Trade". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 12 (3): 277–288. doi:10.1017/S1356186302000329.

- Sharma, Arvind (2005), "Dr. BR Ambedkar on the Aryan invasion and the emergence of the caste system in India", Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 73 (3): 843–870, doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfi081,

[Paraphrasing B. R. Ambedkar]: "The fact that the word Dāsa later came to mean a slave may not by itself indicate such a status of the original people, for a form of the word "Aryan" also means a slave.

- West, Barbara (2008). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase. p. 182. ISBN 978-0816071098.

- Manusmriti with the Commentary of Medhatithi by Ganganatha Jha, 1920, ISBN 8120811550

- Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education. p. 191. ISBN 9788131711200.

- Jaiswal, Suvira (1981). "Women in Early India: Problems and Perspectives". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 42: 55. JSTOR 44141112.

- Stephanie Jamison; Joel Brereton (2014). The Rigveda: 3-Volume Set. Oxford University Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-19-972078-1.

- Thomas R. Trautmann (2006). Aryans and British India. Yoda Press. pp. 213–215. ISBN 978-81-902272-1-6.

- Asko Parpola (2015). The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0-19-022691-6.

- Micheline Ishay (2008). The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalization Era. University of California Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-520-25641-5.

- Gregory Schopen (2004). Buddhist Monks and Business Matters: Still More Papers on Monastic Buddhism in India. University of Hawaii Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-8248-2547-8.

- Gregory Schopen (2004), Buddhist Monks and Business Matters, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0824827748, page 202-206

- Gregory Schopen (1994). "The Monastic Ownership of Servants and Slaves". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 17 (2): 156–162 with footnotes, context: 145–174.

- Gregory Schopen (2010). "On Some Who Are Not Allowed to Become Buddhist Monks or Nuns: An Old List of Types of Slaves or Unfree Laborers". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 130 (2): 225–234 with footnotes.

- Gregory Schopen (1994). "The Monastic Ownership of Servants and Slaves". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 17 (2): 169–171 with footnotes, context: 145–174.

- Gregory Schopen (2010). "On Some Who Are Not Allowed to Become Buddhist Monks or Nuns: An Old List of Types of Slaves or Unfree Laborers". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 130 (2): 231–232 with footnotes.

- Kauṭalya; R. P. Kangle (1986). The Kautiliya Arthasastra, Part 2. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 235–236. ISBN 978-81-208-0042-7.

- Kautilya; Patrick Olivelle (Transl) (2013). King, Governance, and Law in Ancient India: Kautilya's Arthasastra. Oxford University Press. pp. 208–209, 614. ISBN 978-0-19-989182-5.

- Kauṭalya; R. P. Kangle (1972). The Kautiliya Arthasastra, Part 3. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-81-208-0042-7.

- R.P. Kangle (1960), The Kautiliya Arthasastra - a critical edition, Part 3, University of Bombay Studies, ISBN 978-8120800427, page 186

- निष्पातित Sanskrit English dictionary

- Shamasastry (Translator, 1915), Arthashastra of Chanakya

- Rajendra Prasad (1992). Dr. Rajendra Prasad: Correspondence and Select Documents : Presidency Period. Allied Publishers. p. 508. ISBN 978-81-7023-343-5.

- Charlotte Vaudeville (1993). A weaver named Kabir: selected verses with a detailed biographical and historical introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-19-563078-7.

- Andre Wink (1991), Al-Hind: the Making of the Indo-Islamic World, vol. 1, Brill Academic (Leiden), ISBN 978-9004095090, pages 14-15

- Hasan, Mohibbul (2005). Kashmir Under The Sultans. p. 244. ISBN 9788187879497.

- Andre Wink (1991), Al-Hind: the Making of the Indo-Islamic World, vol. 1, Brill Academic (Leiden), ISBN 978-9004095090, pages 172-173

- Muhammad Qasim Firishta, Tarikh-i-Firishta (Lucknow, 1864).

- Andre Wink, Al-Hind: the Making of the Indo-Islamic World, vol. 2, The Slave Kings and the Islamic Conquest, 11th–13th Centuries (Leiden, 1997)

- Hardy, Peter. Muslims of British India. Cambridge University Press. p. 9.

- Scott C. Levi (2002). "Hindus Beyond the Hindu Kush: Indians in the Central Asian Slave Trade". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press. 12 (3): 284.https://www.jstor.org/stable/25188289?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Raychaudhuri and Habib, The Cambridge Economic History of India, I

- Kidwai, "Sultans, Eunuchs and Domestics"

- Zia ud-Din Barani, Tarikh-i-Firuz Shahi, edited by Saiyid Ahmad Khan, William Nassau Lees and Kabiruddin, Bib. Ind. (Calcutta, 1860–62),

- Niccolao Manucci, Storia do Mogor, or Mogul India 1653–1708, 4 vols, translated by W. Irvine (London, 1907-8), II

- Sebastian Manrique, Travels of Frey Sebastian Manrique, 2 vols, translated by Eckford Luard (London, 1906), II

- Francois Bernier, Travels in the Mogul Empire, AD 1656–1668, revised by Vincent Smith (Oxford, 1934)

- Kidwai, "Sultans, Eunuchs and Domestics",

- Lal, Slavery in India

- The sultans and their Hindu subjects' in Jackson, The Delhi Sultanate,

- Minhaj us-Siraj Jurjani, Tabaqat-i Nasiri, translated by H. G. Raverty, 2 vols (New Delhi, 1970), I,

- Barani, Tarikh-i-Firuz Shahi

- Shams-i Siraj Tarikh-i-Fruz Shahi, Bib. Ind. (Calcutta, 1890)

- Vincent A. Smith, Oxford History of India, 3rd ed. (Oxford, 1961),

- Jackson, The Delhi Sultanate,

- Bhanwarlal Nathuram Luniya (1967). Evolution of Indian culture, from the earliest times to the present day. Lakshini Narain Agarwal. p. 392. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- P. N. Ojha (1978). Aspects of medieval Indian society and culture. B.R. Pub. Corp. ISBN 9788170180241. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- Arun Bhattacharjee (1988). Bhāratvarsha: an account of early India with special emphasis on social and economic aspects. Ashish Pub. House. p. 126. ISBN 978-81-7024-169-0. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- Radhakamal Mukerjee (1958). A history of Indian civilisation, Volume 2. Hind Kitabs. p. 132. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- Richard Bulliet; Pamela Kyle Crossley; Daniel Headrick; Steven Hirsch; Lyman Johnson (2008). The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History. Cengage Learning. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-618-99221-8. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- Khwajah Ni‘mat Allah, Tārīkh-i-Khān Jahānī wa makhzan-i-Afghānī, ed. S. M. Imam al-Din (Dacca: Asiatic Society of Pakistan Publication No. 4, 1960), 1: 411.

- Chatterjee, Indrani (2006). Slavery and South Asian History. pp. 10–13. ISBN 978-0-253-21873-5. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Francisco Pelsaert, A Dutch Chronicle of Mughal India, translated and edited by Brij Narain and Sri Ram Sharma (Lahore, 1978), p. 48.

- Sebastian Manrique, Travels of Frey Sebastian Manrique, 2 vols, translated by Eckford Luard (London, 1906), II,

- https://web.archive.org/web/20190327142056/https://www.rct.uk/collection/1005025-ag/the-departure-of-prince-shah-shuja-for-kabul-16-march-1638

- Badshah Nama, Qazinivi & Badshah Nama, Abdul Hamid Lahori

- Said Ali ibn Said Muhammad Bukhari, Khutut-i mamhura bemahr-i qadaah-i Bukhara, OSIASRU, Ms. No. 8586/II. For bibliographic information, see Sobranie vostochnykh rukopisei Akademii Nauk Uzbekskoi SSR, 11 vols (Tashkent, 1952–85).

- The Administration of Justice in Medieval India, MB Ahmad, The Aligarh University (1941)

- M. Reza Pirbhai (2009), Reconsidering Islam in a South Asian Context, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004177581, pp. 131-154

- Fatawa i-Alamgiri, Vol 5, p. 273 - Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980)

- A digest of the Moohummudan law pp. 386 with footnote 1, Neil Baillie, Smith Elder, London

- Fatawa i-Alamgiri, Vol 1, pp. 395-397; Fatawa-i Alamgiri, Vol 1, pp. 86-88, Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980)

- Fatawa i-Alamgiri, Vol 6, p. 631 - Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980); The Muhammadan Law p. 275 annotations

- A digest of the Moohummudan law pp. 371 with footnote 1, Neil Baillie, Smith Elder, London

- Fatawa i-Alamgiri, Vol 1, page 377 - Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980); The Muhammadan Law p. 298 annotations

- Fatawa i-Alamgiri, Vol 1, pp. 394-398 - Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980)

- Muhammad Talib, Malab al-alibn, Oriental Studies Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan , Ms. No. 80, fols 117a-18a.

- Peter Jackson, The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History (Cambridge, 1999), See also Indian textile industry in Scott Levi, The Indian Diaspora in Central Asia and its Trade, 1550–1900 (Leiden, 2002)

- Beatrice Manz, The Rise and Rule of Tamerlane (Cambridge, 1989); Tapan Raychaudhuri and Irfan Habib, eds, The Cambridge Economic History of India, vol. 1, (Hyderabad, 1984); Surendra Gopal, 'Indians in Central Asia, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries', Presidential Address, Medieval India Section of the Indian History Congress, New Delhi, February 1992 (Patna, 1992)

- E. K. Meyendorff, Puteshestvie iz Orenburga v Bukharu, Russian translation by N. A. Khalin (Moscow, 1975),

- Chatterjee, Gender, Slavery and Law in Colonial India, p. 223.

- "The Tribune - Windows - Slice of history".

- S. Subrahmanyam, "Slaves and Tyrants: Dutch Tribulations in Seventeenth-Century Mrauk-U," Journal of Early Modern History 1, no. 3 (August 1997); O. Prakash, European Commercial Enterprise in Pre-Colonial India, The New Cambridge History of India II:5 (New York, 1998); O. Prakash, The Dutch East India Company and the Economy of Bengal; J. F. Richards, The Mughal Empire, The New Cambridge History of India I:5 (New York, 1993),; Raychaudhuri and Habib, eds., The Cambridge Economic History of India I,; V. B. Lieberman, Burmese Administrative Cycles: Anarchy and Conquest, c. 1580–1760 (Princeton, N.J., 1984); G. D. Winius, "The 'Shadow Empire' of Goa in the Bay of Bengal," Itinerario 7, no. 2 (1983):; D.G.E. Hall, "Studies in Dutch relations with Arakan," Journal of the Burma Research Society 26, no. 1 (1936):; D.G.E. Hall, "The Daghregister of Batavia and Dutch Trade with Burma in the Seventeenth Century," Journal of the Burma Research Society 29, no. 2 (1939); Arasaratnam, "Slave Trade in the Indian Ocean in the Seventeenth Century,".

- VOC 1479, OBP 1691, fls. 611r-627v, Specificatie van Allerhande Koopmansz. tot Tuticurin, Manaapar en Alvatt.rij Ingekocht, 1670/71-1689/90; W. Ph. Coolhaas and J.van Goor, eds., Generale Missiven van Gouverneurs-Generaal en Raden van Indiaan Heren Zeventien der Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (The Hague, 1960–present), passim; T. Raychaudhuri, Jan Company in Coromandel, 1605–1690: A Study on the Interrelations of European Commerce and Traditional Economies (The Hague, 1962); S. Arasaratnam, "Slave Trade in the Indian Ocean in the Seventeenth Century," in K. S. Mathew, ed., Mariners, Merchants and Oceans: Studies in Maritime History (New Delhi, 1995).

- For exports of Malabar slaves to Ceylon, Batavia, see Generale Missiven VI,; H.K. s'Jacob ed., De Nederlanders in Kerala, 1663–1701: De Memories en Instructies Betreffende het Commandement Malabar van de Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, Rijks Geschiedkundige Publication, Kleine serie 43 (The Hague, 1976),; R. Barendse, "Slaving on the Malagasy Coast, 1640–1700," in S. Evers and M. Spindler, eds., Cultures of Madagascar: Ebb and Flow of Influences (Leiden, 1995). See also M. O. Koshy, The Dutch Power in Kerala (New Delhi, 1989); K. K. Kusuman, Slavery in Travancore (Trivandrum, 1973); M.A.P. Meilink-Roelofsz, De Vestiging der Nederlanders ter Kuste Malabar (The Hague, 1943); H. Terpstra, De Opkomst der Westerkwartieren van de Oostindische Compagnie (The Hague, 1918).

- M.P.M. Vink, "Encounters on the Opposite Coast: Cross-Cultural Contacts between the Dutch East India Company and the Nayaka State of Madurai in the Seventeenth Century," unpublished dissertation, University of Minnesota (1998); Arasaratnam, Ceylon and the Dutch, 1600–1800 (Great Yarmouth, 1996); H. D. Love, Vestiges from Old Madras (London, 1913).

- Of 2,467 slaves traded on 12 slave voyages from Batavia, India, and Madagascar between 1677 and 1701 to the Cape, 1,617 were landed with a loss of 850 slaves, or 34.45%. On 19 voyages between 1677 and 1732, the mortality rate was somewhat lower (22.7%). See Shell, "Slavery at the Cape of Good Hope, 1680–1731," p. 332. Filliot estimated the average mortality rate among slaves shipped from India and West Africa to the Mascarene Islands at 20–25% and 25–30%, respectively. Average mortality rates among slaves arriving from closer catchment areas were lower: 12% from Madagascar and 21% from Southeast Africa. See Filliot, La Traite des Esclaves, p. 228; A. Toussaint, La Route des Îles: Contribution à l'Histoire Maritime des Mascareignes (Paris, 1967),; Allen, "The Madagascar Slave Trade and Labor Migration."

- Hansard Parliamentary Papers 125 (1828), 128 (1834), 697 (1837), 238 (1841), 525 (1843), 14 (1844), London, House of Commons

- Sen, Jahar (1973). "Slave trade on the Indo-Nepal border, in the 19th century" (PDF). Calcutta: 159 – via Cambridge Apollo.

- Slavery and the slave trade in British India; with notices of the existence of these evils in the islands of Ceylon, Malacca, and Penang, drawn from official documents

- The Law and Custom of Slavery in British India: In a Series of Letters to Thomas Fowell Buxton, Esq

- The British and Foreign Anti-slavery Reporter, Volumes 1-3

- Andrea Major (2012). Slavery, Abolitionism and Empire in India, 1772-1843. Liverpool University Press. pp. 43–54. ISBN 978-1-84631-758-3.

- John Griffith (1986), What is legal pluralism?, The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law, Volume 18, Issue 24, pages 1-55

- An Act for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Colonies 3° & 4° Gulielmi IV, cap. LXXIII (August 1833)

- "Slavery In British India : Banaji, D. R. : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Internet Archive. 1 July 2015. p. 202. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Walker, Timothy (2004). "Abolishing the slave trade in Portuguese India: documentary evidence of popular and official resistance to crown policy, 1842–60". Slavery & Abolition. 25 (2): 63–79. doi:10.1080/0144039042000293045. S2CID 142692153.

- Peabody, Sue (2014). "French Emancipation". doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199730414-0253. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Islamic Law and the Colonial Encounter in British India Archived 29 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Campbell, G. (Ed.). (2005). Abolition and Its Aftermath in the Indian Ocean Africa and Asia. London: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203493021

- Viswanath, Rupa (29 July 2014), The Pariah Problem: Caste, Religion, and the Social in Modern India, Columbia University Press, p. 5, ISBN 978-0-231-53750-6

- Walton Lai (1993). Indentured labor, Caribbean sugar: Chinese and Indian migrants to the British West Indies, 1838–1918. ISBN 978-0-8018-7746-9.

- Steven Vertovik (Robin Cohen, ed.) (1995). The Cambridge survey of world migration. pp. 57–68. ISBN 978-0-521-44405-7.

- Tinker, Hugh (1993). New System of Slavery. Hansib Publishing, London. ISBN 978-1-870518-18-5.

- Sheridan, Richard B. (2002). "The Condition of slaves on the sugar plantations of Sir John Gladstone in the colony of Demerara 1812 to 1849". New West Indian Guide. 76 (3/4): 265–269. doi:10.1163/13822373-90002536.

- "Forced Labour". The National Archives, Government of the United Kingdom. 2010.

- K Laurence (1994). A Question of Labour: Indentured Immigration Into Trinidad & British Guiana, 1875–1917. St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-12172-3.

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/8-million-people-live-in-modern-slavery-in-india-says-report-govt-junks-claim/articleshow/65060986.cms

- Browne, Rachel (31 May 2016). "Andrew Forrest puts world's richest countries on notice: Global Slavery Index". Sydney Morning Herald. Australia. Fairfax. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Gladstone, Rick (31 May 2016). "Modern Slavery Estimated to Trap 45 Million People Worldwide". The New York Times.

- "India".

- "Bonded labourers, sex workers, forced beggars: India leads world in slavery". 31 May 2016.

- Mazumdar, Rakhi (June 2016). "India ranks fourth in global slavery survey". The Economic Times.

- Vilasetuo Suokhrie, "Human Market for Sex & Slave?!!", The Morung Express (8 April 2008)

- Choi-Fitzpatrick, Austin (7 March 2017). What Slaveholders Think: How Contemporary Perpetrators Rationalize What They do. ISBN 9780231543828.

- "Modern slavery and child labour in Indian quarries - Stop Child Labour". Stop Child Labour. 11 May 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- "Modern slavery and child labour in Indian quarries". www.indianet.nl. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

Further reading

- Scott C. Levi (2002), Hindus Beyond the Hindu Kush: Indians in the Central Asian Slave Trade, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society

- Lal, K. S. (1994). Muslim slave system in medieval India. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

- Salim Kidwai, "Sultans, Eunuchs and Domestics: New Forms of Bondage in Medieval India", in Utsa Patnaik and Manjari Dingwaney (eds), Chains of Servitude: bondage and slavery in India (Madras, 1985).

- Utsa Patnaik and Manjari Dingwaney (eds), Chains of Servitude: bondage and slavery in India (Madras, 1985)

- Andrea Major (2014), Slavery, Abolitionism and Empire in India, 1772–1843, Liverpool University Press,

- R.C. Majumdar, The History and Culture of the Indian People, Bombay.

- Andre Wink (1991), Al-Hind: the Making of the Indo-Islamic World, Brill Academic (Leiden), ISBN 978-9004095090

- KT Rammohan (2009). 'Modern Bondage: Atiyaayma in Post-Abolition Malabar'. in Jan Breman, Isabelle Guerin and Aseem Prakash (eds). India's Unfree Workforce: Of Bondage Old and New. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-019-569846-6

External links

- The law and custom of slavery in British India in a series of letters to Thomas Fowell Buxton, esq., by William Adam., 1840 Open Library

- Modern Slavery, Human bondage in Africa, Asia, and the Dominican Republic

- The Small Hands of Slavery, Bonded Child Labor In India

- India – bonded labour: the gap between illusion and reality

- Child Slaves in Modern India: The Bonded Labor Problem

- Legislative Redress Rather Than Progress? From Slavery to Bondage in Colonial India by Stefan Tetzlaff