British rule in Burma

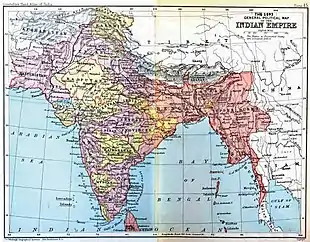

British rule in Burma lasted from 1824 to 1948, from the successive three Anglo-Burmese wars through the creation of Burma as a Province of British India to the establishment of an independently administered colony, and finally independence. The region under British control was known as British Burma. Various portions of Burmese territories, including Arakan (Rakhine State) or Tenasserim were annexed by the British after their victory in the First Anglo-Burmese War; Lower Burma was annexed in 1852 after the Second Anglo-Burmese War. The annexed territories were designated the minor province (a chief commissionership) of British India in 1862.[2]

Colony of Burma မြန်မာကိုလိုနီ | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1824–1948 | |||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Flag

(1939–1948) | |||||||||||||||||

British Burma during World War II Dark green: Japanese occupation of Burma Light silver: Remainder of British Burma Light green: Occupied and annexed by Thailand | |||||||||||||||||

| Status | Division of the Bengal Presidency (1826–1862) Province of British India (1862–1937) Colony of the United Kingdom (1937–1948) | ||||||||||||||||

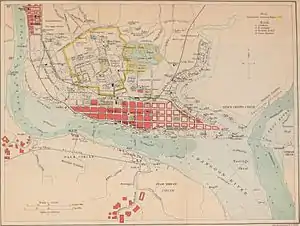

| Capital | Moulmein (1826–1852) Rangoon (1853–1942) Shimla (1942-1945) Rangoon (1945–1948) | ||||||||||||||||

| Capital-in-exile | Shimla, British India (1942–1945) | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | English (official) Burmese | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam | ||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||

• 1862–1901 | Victoria | ||||||||||||||||

• 1901–1910 | Edward VII | ||||||||||||||||

• 1910–1936 | George V | ||||||||||||||||

• 1936 | Edward VIII | ||||||||||||||||

• 1936–1948 | George VI | ||||||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||||||

• 1862–1867 (first) | Sir Arthur Purves Phayre[1] | ||||||||||||||||

• 1946–1948 (last) | Sir Hubert Rance | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Legislative Council of Burma (1897–1936) Legislature of Burma (1936–1947) | ||||||||||||||||

| Senate | |||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | |||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Colonial era | ||||||||||||||||

| 5 March 1824 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1824–1826, 1852, 1885 | |||||||||||||||||

• Separation from British India | 1937 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1942–1945 | |||||||||||||||||

• Independence from the United Kingdom | 4 January 1948 | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Burmese rupee, Indian rupee, Pound sterling | ||||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | MM | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||

After the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885, Upper Burma was annexed, and the following year, the province of Burma in British India was created, becoming a major province (a lieutenant-governorship) in 1897.[2] This arrangement lasted until 1937, when Burma began to be administered separately by the Burma Office under the Secretary of State for India and Burma. British rule was disrupted during the Japanese occupation of much of the country during the World War II. Burma achieved independence from British rule on 4 January 1948.

Burma is sometimes referred to as "the Scottish Colony" owing to the heavy role played by Scotsmen in colonising and running the country, one of the most notable being Sir James Scott.

| History of Myanmar |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

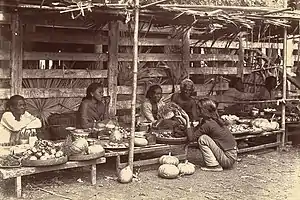

Prior to British conquest

Because of its location, trade routes between China and India passed through the country, keeping Burma wealthy through trade, although self-sufficient agriculture was still the basis of the economy. Indian merchants traveled along the coasts and rivers (especially the Irrawaddy River) throughout the regions where the majority of Burmese lived, bringing Indian cultural influences into the country that still exist there today. As Burma had been one of the first Southeast Asian countries to adopt Buddhism on a large scale, it continued under the British as the officially patronised religion of most of the population.[3]

Before the British conquest and colonisation, the ruling Konbaung dynasty practiced a tightly centralized form of government. The king was the chief executive with the final say on all matters, but he could not make new laws and could only issue administrative edicts. The country had two codes of law, the Dhammathat and the Hluttaw, the center of government, was divided into three branches—fiscal, executive, and judicial. In theory, the king was in charge of all of the Hluttaw, but none of his orders got put into place until the Hluttaw approved them, thus checking his power. Further dividing the country, provinces were ruled by governors, who were appointed by the Hluttaw, and villages were ruled by hereditary headmen approved by the king.[4]

Arrival of the British

Conflict began between Burma and the British when the Konbaung dynasty decided to expand into Arakan in the state of Assam, close to British-held Chittagong in India. This led to the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–26). The British dispatched a large seaborne expedition that took Rangoon without a fight in 1824. In Danuphyu, at the Ayeyarwadddy Delta, Burmese General Maha Bandula was killed and his armies routed. Burma was forced to cede Assam and other northern provinces.[5] The 1826 Treaty of Yandabo formally ended the First Anglo-Burmese War, the longest and the most expensive war in the history of British India. Fifteen thousand European and Indian soldiers died, together with an unknown number of Burmese army and civilian casualties.[6] The campaign cost the British between 5 and 13 million pounds sterling (between 18 and $48 billion in 2020 U.S. dollars)[7] which led to an economic crisis in British India in 1833.[8]

In 1852, the Second Anglo-Burmese War was provoked by the British, who sought the teak forests in Lower Burma as well as a port between Calcutta and Singapore. After 25 years of peace, British and Burmese fighting started afresh and continued until the British occupied all of Lower Burma. The British were victorious in this war and as a result obtained access to the teak, oil, and rubies of their newly conquered territories.

In Upper Burma, the still unoccupied part of the country, King Mindon had tried to adjust to the thrust of imperialism. He enacted administrative reforms and made Burma more receptive to foreign interests. But the British initiated the Third Anglo-Burmese War, which lasted less than two weeks during November 1885. The British government justified their actions by claiming that the last independent king of Burma, Thibaw Min, was a tyrant and that he was conspiring to give France more influence in the country. British troops entered Mandalay on 28 November 1885. Thus, after three wars gaining various parts of the country, the British occupied all the area of present-day Myanmar, making the territory a Province of British India on 1 January 1886.[4][9]

Early British rule

Imperial entities of India | |

| Dutch India | 1605–1825 |

|---|---|

| Danish India | 1620–1869 |

| French India | 1668–1954 |

| Casa da Índia | 1434–1833 |

| Portuguese East India Company | 1628–1633 |

| East India Company | 1612–1757 |

| Company rule in India | 1757–1858 |

| British Raj | 1858–1947 |

| British rule in Burma | 1824–1948 |

| Princely states | 1721–1949 |

| Partition of India | 1947 |

Burmese armed resistance continued sporadically for several years, and the British commander had to coerce the High Court of Justice to continue to function. Though war officially ended after only a couple of weeks, resistance continued in northern Burma until 1890, with the British finally resorting to systematic destruction of villages and appointment of new officials to finally halt all guerrilla activity.

Traditional Burmese society was drastically altered by the demise of the monarchy and the separation of religion and state. Intermarriage between Europeans and Burmese gave birth to an indigenous Eurasian community known as the Anglo-Burmese who would come to dominate the colonial society, hovering above the Burmese but below the British.

After Britain took over all of Burma, they continued to send tribute to China to avoid offending them, but this unknowingly lowered the status they held in Chinese minds.[10] It was agreed at the Burma convention in 1886 that China would recognise Britain's occupation of Upper Burma while Britain continued the Burmese payment of tribute every ten years to Peking.[11]

Administration

The British controlled their new province through direct rule, making many changes to the previous governmental structure. The monarchy was abolished, King Thibaw sent into exile, and religion and state separated. This was particularly harmful, because the Buddhist monks, collectively known as the Sangha, were strongly dependent on the sponsorship of the monarchy. At the same time, the monarchy was given legitimacy by the Sangha, and monks as representatives of Buddhism gave the public the opportunity to understand national politics to a greater degree.[4]

The British also implemented a secular education system. The colonial Government of India, which was given control of the new colony, founded secular schools, teaching in both English and Burmese, while also encouraging Christian missionaries to visit and found schools. In both of these types of schools, Buddhism and traditional Burmese culture was frowned upon.[4]

Divisions

The province of Burma, after 1885 was administered as follows:

- Ministerial Burma (Burma proper)

- Tenasserim Division (Toungoo, Thaton, Amherst, Salween, Tavoy, and Mergui Districts)

- Arakan Division (Akyab, Northern Arakan or Arakan Hill Tracts, Kyaukpyu and Sandoway Districts)

- Pegu Division (Rangoon City, Hanthawaddy, Pegu, Tharrawaddy and Prome Districts)

- Irrawaddy Division (Bassein, Henzada, Thayetmyo, Maubin, Myaungmya and Pyapon Districts)

- Scheduled Areas (Frontier Areas)

- Shan States

- Pakokku Chin Hills

- Kachin tracts

The "Frontier Areas", also known as the "Excluded Areas" or the "Scheduled Areas", compose the majority of states within Burma today. They were administered separately by the British with a Burma Frontier Service and later united with Burma proper to form Myanmar's geographic composition today. The Frontier Areas were inhabited by ethnic minorities such as the Chin, the Shan, the Kachin and the Karenni.

By 1931 Burma had 9 divisions, split into a number of districts.[12]

- Arakan Division (Akyab, Arakan Hill, Kyaukpyu and Sandoway Districts)

- Minbu Division ( Magway, Minbu and Thayetmyo Districts)

- Mandalay Division (Kyaukse, Mandalay, Meiktila and Myingyan Districts)

- Tenasserim Division (Toungoo, Thaton, Amherst, Salween, Tavoy, and Mergui Districts)

- Pegu Division (Rangoon City, Hanthawaddy, Pegu, Tharrawaddy and Prome Districts)

- Irrawaddy Division (Bassein, Henzada, Maubin, Myaungmya and Pyapon Districts)

- Sagaing Division (Bhamo, Lower Chindwin, Upper Chindwin, Katha, Myitkyina, Sagaing Districts, the Hukawng Valley and The Triangle Native areas)

- Federated Shan States (Northern, Eastern, Central, Myelat, Karenni, Kengtung and Yawnghwe)

- Pakokku Hill Tracts (Chin Hills, Manipur, Lushai Hills , Pakokku District , Cachar and Jaintia )

Economy

The traditional Burmese economy was one of redistribution with the prices of the most important commodities set by the state. For the majority of the population, trade was not as important as self-sufficient agriculture, but the country's position on major trade routes from India to China meant that it did gain a significant amount of money from facilitating foreign trade. With the arrival of the British, the Burmese economy became tied to global market forces and was forced to become a part of the colonial export economy.[4]

Burma's annexation ushered in a new period of economic growth. The economic nature of society also changed dramatically. The British began exploiting the rich soil of the land around the Irrawaddy delta and cleared away the dense mangrove forests. Rice, which was in high demand in Europe, especially after the building of the Suez Canal in 1869, was the main export. To increase the production of rice, many Burmese migrated from the northern heartland to the delta, shifting the population concentration and changing the basis of wealth and power.[4]

To prepare the new land for cultivation, farmers borrowed money from Indian moneylenders called chettiars at high interest rates, as British banks would not grant mortgages. The Indian moneylenders offered mortgage loans but foreclosed on them quickly if the borrowers defaulted.

At the same time, thousands of Indian laborers migrated to Burma (Burmese Indians) and, because of their willingness to work for less money, quickly displaced Burmese farmers. As the Encyclopedia Britannica states: "Burmese villagers, unemployed and lost in a disintegrating society, sometimes took to petty theft and robbery and were soon characterized by the British as lazy and undisciplined. The level of dysfunction in Burmese society was revealed by the dramatic rise in homicides."[13]

With this quickly growing economy came industrialisation to a certain degree, with a railway being built throughout the valley of the Irrawaddy, and hundreds of steamboats traveled along the river. All of these modes of transportation were owned by the British. Thus, although the balance of trade was in favour of British Burma, the society was changed so fundamentally that many people did not gain from the rapidly growing economy.[4]

The civil service was largely staffed by Anglo-Burmese and Indians, and the ethnic Burmese were excluded almost entirely from military service, which was staffed primarily with Indians, Anglo-Burmese, Karens and other Burmese minority groups. A British General Hospital Burmah was set up in Rangoon in 1887.[14] Though the country prospered, the Burmese people largely failed to reap the rewards. (See George Orwell's novel Burmese Days for a fictional account of the British in Burma.) An account by a British official describing the conditions of the Burmese people's livelihoods in 1941 describes the Burmese hardships:

“Foreign landlordism and the operations of foreign moneylenders had led to increasing exportation of a considerable proportion of the country’s resources and to the progressive impoverishment of the agriculturist and of the country as a whole…. The peasant had grown factually poorer and unemployment had increased….The collapse of the Burmese social system led to a decay of the social conscience which, in the circumstances of poverty and unemployment caused a great increase in crime.”[15]

Nationalist movement

By the turn of the century, a nationalist movement began to take shape in the form of the Young Men's Buddhist Association (YMBA), modelled after the YMCA, as religious associations were allowed by the colonial authorities. They were later superseded by the General Council of Burmese Associations (GCBA) which was linked with Wunthanu athin or National Associations that sprang up in villages throughout Burma Proper.[16] Between 1900 and 1911 the "Irish Buddhist" U Dhammaloka publicly challenged Christianity and imperial power, leading to two trials for sedition.

A new generation of Burmese leaders arose in the early twentieth century from amongst the educated classes, some of whom were permitted to go to London to study law. They returned with the belief that the Burmese situation could be improved through reform. Progressive constitutional reform in the early 1920s led to a legislature with limited powers, a university and more autonomy for Burma within the administration of India. Efforts were undertaken to increase the representation of Burmese in the civil service. Some people began to feel that the rate of change was not fast enough and the reforms not extensive enough.

In 1920 a students strike broke out in protest against the new University Act which the students believed would only benefit the elite and perpetuate colonial rule. 'National Schools' sprang up across the country in protest against the colonial education system, and the strike came to be commemorated as 'National Day'.[16] There were further strikes and anti-tax protests in the later 1920s led by the Wunthanu athins. Prominent among the political activists were Buddhist monks (hpongyi), such as U Ottama and U Seinda in the Arakan who subsequently led an armed rebellion against the British and later the nationalist government after independence, and U Wisara, the first martyr of the movement to die after a protracted hunger strike in prison.[16]

In December 1930, a local tax protest by Saya San in Tharrawaddy quickly grew into first a regional and then a national insurrection against the government. Lasting for two years, the Galon rebellion, named after the mythical bird Garuda – enemy of the Nagas i.e. the British – emblazoned on the pennants the rebels carried, required thousands of British troops to suppress along with promises of further political reform. The eventual trial of Saya San, who was executed, allowed several future national leaders, including Dr Ba Maw and U Saw, who participated in his defense, to rise to prominence.[16]

In May 1930, the Dobama Asiayone (We Burmans Association) was founded, whose members called themselves Thakin (an ironic name as thakin means "master" in the Burmese language – rather like the Indian 'sahib' – proclaiming that they were the true masters of the country entitled to the term usurped by the colonial masters).[16] The second university students strike in 1936 was triggered by the expulsion of Aung San and Ko Nu, leaders of the Rangoon University Students Union, for refusing to reveal the name of the author who had written an article in their university magazine, making a scathing attack on one of the senior university officials. It spread to Mandalay leading to the formation of the All Burma Students Union. Aung San and Nu subsequently joined the Thakin movement progressing from student to national politics.[16]

Separation from India

The British separated Burma Province from British India in 1937[17] and granted the colony a new constitution calling for a fully elected assembly, with many powers given to the Burmese, but this proved to be a divisive issue as some Burmese felt that this was a ploy to exclude them from any further Indian reforms. Ba Maw served as the first prime minister of Burma, but he was forced out by U Saw in 1939, who served as prime minister from 1940 until he was arrested on 19 January 1942 by the British for communicating with the Japanese.

A wave of strikes and protests that started from the oilfields of central Burma in 1938 became a general strike with far-reaching consequences. In Rangoon student protesters, after successfully picketing the Secretariat, the seat of the colonial government, were charged by the British mounted police wielding batons and killing Rangoon University student. In Mandalay, the police shot into a crowd of protesters led by Buddhist monks killing 17 people. The movement became known as Htaung thoun ya byei ayeidawbon (the '1300 Revolution' named after the Burmese calendar year),[16] and 20 December, the day the first martyr Aung Kyaw fell, commemorated by students as 'Bo Aung Kyaw Day'.[18]

World War II

The Empire of Japan invaded Burma in 1942; this continued through 1943 when the State of Burma was proclaimed in Rangoon. Japan never succeeded in fully conquering all of the colony, however, and insurgent activity was pervasive, though not as much of an issue as it was in other former colonies. By 1945, British-led troops, mainly from the British Indian Army, had regained control over most of the colony.

From the Japanese surrender to Aung San's assassination

The surrender of the Japanese brought a military administration to Burma. The British administration sought to try Aung San and other members of the British Indian Army for treason and collaboration with the Japanese.[19] Lord Mountbatten realised that a trial was an impossibility considering Aung San's popular appeal.[16] After the war ended, the British Governor, Colonel Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, returned. The restored government established a political programme that focused on the physical reconstruction of the country and delayed discussion of independence. The Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League (AFPFL) opposed the government leading to political instability in the country. A rift had also developed in the AFPFL between the communists and Aung San together with the socialists over strategy, which led to Than Tun being forced to resign as general secretary in July 1946 and the expulsion of the CPB from the AFPFL the following October.[16]

Dorman-Smith was replaced by Major-General Sir Hubert Rance as the new governor, and the Rangoon police went on strike. The strike, starting in September 1946, then spread from the police to government employees and came close to becoming a general strike. Rance calmed the situation by meeting with Aung San and convincing him to join the Governor's Executive Council along with other members of the AFPFL.[16] The new executive council, which now had increased credibility in the country, began negotiations for Burmese independence, which were concluded successfully in London as the Aung San-Attlee Agreement on 27 January 1947.[16]

The agreement left parts of the communist and conservative branches of the AFPFL dissatisfied, sending the Red Flag Communists led by Thakin Soe underground and the conservatives into opposition. Aung San also succeeded in concluding an agreement with ethnic minorities for a unified Burma at the Panglong Conference on 12 February, celebrated since as 'Union Day'.[16][20] Shortly after, rebellion broke out in the Arakan led by the veteran monk U Seinda, and it began to spread to other districts.[16] The popularity of the AFPFL, dominated by Aung San and the socialists, was eventually confirmed when it won an overwhelming victory in the April 1947 constituent assembly elections.[16]

Then a momentous event stunned the nation on 19 July 1947. U Saw, a conservative pre-war Prime Minister of Burma, engineered the assassination of Aung San and several members of his cabinet including his eldest brother Ba Win, the father of today's National League for Democracy exile-government leader Dr Sein Win, while meeting in the Secretariat.[16][21] Since then 19 July has been commemorated since as Martyrs' Day in Burma. Thakin Nu, the Socialist leader, was now asked to form a new cabinet, and he presided over Burmese independence instituted under the Burma Independence Act 1947 on 4 January 1948. Burma chose to become a fully independent republic, and not a British Dominion upon independence. This was in contrast to the independence of India and Pakistan which both resulted in the attainment of dominion status. This may have been on account of anti-British popular sentiment being strong in Burma at the time.[16]

See also

References

Citations

- Chief Commisoner

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1908, p. 29

- For the history of all major religious groups in Burma and modern Myanmar, see the article on Religion in Myanmar.

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- World Book Encyclopedia

- Thant Myint-U (2001). The Making of Modern Burma. Cambridge University Press. pp. 18. ISBN 0-521-79914-7.

- Thant Myint-U (2006). The River of Lost Footsteps—Histories of Burma. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 113, 125–127. ISBN 978-0-374-16342-6.

- Webster, Anthony (1998). Gentlemen Capitalists: British Imperialism in South East Asia, 1770–1890. I.B.Tauris. pp. 142–145. ISBN 978-1-86064-171-8.

- Dictionary of Indian Biography. Ardent Media. 1906. p. 82. GGKEY:BDL52T227UN.

- Alfred Stead (1901). China and her mysteries. LONDON: Hood, Douglas, & Howard. p. 100. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

burma was a tributary state of china british forward tribute peking.

(Original from the University of California) - William Woodville Rockhill (1905). China's intercourse with Korea from the XVth century to 1895. LONDON: Luzac & Co. p. 5. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

tribute china.

(Colonial period Korea ; WWC-5)(Original from the University of California) - Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. XXVI 1931

- "Myanmar - The initial impact of colonialism". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Service record held in Army Medical Service Museum, Aldershot, page 145, return no 5155.

- Chew, Ernest (1969). "The Withdrawal of the Last British Residency from Upper Burma in 1879". Journal of Southeast Asian History. 10 (2): 253–278. doi:10.1017/S0217781100004403. JSTOR 20067745.

- Martin Smith (1991). Burma – Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London and New Jersey: Zed Books. pp. 49, 91, 50, 53, 54, 56, 57, 58–59, 60, 61, 60, 66, 65, 68, 69, 77, 78, 64, 70, 103, 92, 120, 176, 168–169, 177, 178, 180, 186, 195–197, 193, 202, 204, 199, 200, 270, 269, 275–276, 292–3, 318–320, 25, 24, 1, 4–16, 365, 375–377, 414.

- Sword For Pen, TIME Magazine, 12 April 1937

- "The Statement on the Commemoration of Bo Aung Kyaw". All Burma Students League. 19 December 1999. Retrieved 23 October 2006.

- Stephen Mccarthy (2006). The Political Theory of Tyranny in Singapore and Burma. Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 0-415-70186-4.

- "The Panglong Agreement, 1947". Online Burma/Myanmar Library.

- "Who Killed Aung San? – an interview with Gen. Kyaw Zaw". The Irrawaddy. August 1997. Archived from the original on 19 August 2006. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

Sources

- Chew, Ernest. "The Withdrawal of the Last British Residency from Upper Burma in 1879." Journal of Southeast Asian History 10.2 (1969): 253–78. Jstor. Web. 1 March 2010. http://jstor.org/stable/20067745

- "CIA – The World Factbook." Welcome to the CIA Web Site Central Intelligence Agency. 18 February 2010. Web. 4 March 2010. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-%5B%5D

- factbook/geos/countrytemplate_bm.html

- Encyclopædia Britannica. Web. 1 March 2010. <https://web.archive.org/web/20110726001100/http://media-2.web.britannica.com/eb-media/35/4035-004-4ECC016C.gif%3E.

- Furnivall, J. S. "Burma, Past and Present." Far Eastern Survey: American Institute of Pacific Relations 25 February 1953, XXII ed., No. 3 sec.: 21–26. JStor. Web. 1 March 2010. http://jstor.org/stable/3024126

- Guyot, James F. "Myanmar." The World Book Encyclopedia; Vol. 13. Chicago: World Book, 2004. 970-70e. Print.

- Marshall, Andrew. The Trouser People: A Story of Burma in the Shadow of the Empire. Washington D.C.: Counterpoint, 2002. Print.

- "Myanmar (Burma) – Charles' George Orwell Links." Charles' George Orwell Links – Biographies, Essays, Novels, Reviews, Images. Web. 4 March 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20110923185216/http://www.netcharles.com/orwell/articles/col-burma.htm

- "Myanmar." Encyclopædia Britannica. 15th ed. 2005. Print.

- Tucker, Shelby. Burma: The Curse of Independence. London: Pluto, 2001. Print.

This article incorporates text from China and her mysteries, by Alfred Stead, a publication from 1901, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from China and her mysteries, by Alfred Stead, a publication from 1901, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from China's intercourse with Korea from the XVth century to 1895, by William Woodville Rockhill, a publication from 1905, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from China's intercourse with Korea from the XVth century to 1895, by William Woodville Rockhill, a publication from 1905, now in the public domain in the United States.

Further reading

- Baird-Murray, Maureen [1998]. A World Overturned: a Burmese Childhood 1933–47. London: Constable. ISBN 0094789207 Memoirs of the Anglo-Irish-Burmese daughter of a Burma Frontier Service officer, including her stay in an Italian convent during the Japanese occupation.

- Charney, Michael (2009). A History of Modern Burma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Desai, Walter Sadgun (1968). History of the British Residency in Burma. London: Gregg International. ISBN 0-576-03152-6.

- Fryer, Frederick William Richards (1905). . The Empire and the century. London: John Murray. pp. 716–727.

- Harvey, Godfrey (1992). British Rule in Burma 1824–1942. London: AMS Pr. ISBN 0-404-54834-2.

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV (1908), The Indian Empire, Administrative, Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, pp. xxx, 1 map, 552

- Naono, Atsuko (2009). State of Vaccination: The Fight Against Smallpox in Colonial Burma. Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan. p. 238. ISBN 978-81-250-3546-6. ( http://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/4729301/Cite)

- Richell, Judith L. (2006). Disease and Demography in Colonial Burma. Singapore: NUS Press. p. 238.

- Myint-U, Thant (2008). The River of Lost Footsteps: a Personal History of Burma. London: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

External links

- J. S. Furnivall, "Burma, Past and Present", Far Eastern Survey, Vol. 22, No. 3 (25 February 1953), pp. 21–26, Institute of Pacific Relations. <http://jstor.org/stable/3024126>

- Ernest Chew, "The Withdrawal of the Last British Residency from Upper Burma in 1879", Journal of Southeast Asian History, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Sep. 1969), pp. 253–278, Cambridge University Press. <http://jstor.org/stable/20067745>

- Michael W. Charney: Burma, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

.svg.png.webp)