Sobekneferu

Sobekneferu (sometimes written "Neferusobek") reigned as Pharaoh of Egypt after the death of Amenemhat IV. She was the last ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt and ruled Egypt for approximately four years from 1806 to 1802 BC.[1] Her name means "the beauty of Sobek".

| Sobekneferu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neferusobek Skemiophris (in Manetho) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

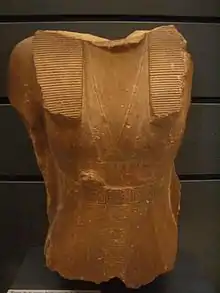

.jpg.webp) Statue of Sobekneferu, Pharaoh of Egypt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1806–1802 BC (Twelfth Dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Amenemhat IV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | uncertain, Sekhemre Khutawy Sobekhotep[1] or, in older studies, Wegaf | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Amenemhat III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1802 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Northern Mazghuna pyramid (?) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Family

Sobekneferu was the daughter of Pharaoh Amenemhat III. Manetho's Aegyptiaca states that she also was the sister of Amenemhat IV, but this claim is unproven. Researchers have yet to find proof of Manetho's claim and none of Sobekneferu's documented titles support the claim.

Sobekneferu had an older sister named Neferuptah, who was the heir next in line after Amenemhat IV. Neferuptah's name was enclosed in a cartouche and she had her own pyramid at Hawara. Neferuptah died at an early age, however, putting Sobekneferu as be next in line.[2]

Reign

Sobekneferu is the first woman for whom there is confirmed proof that she reigned as Pharaoh of Egypt.[3] There are earlier women who are known to have ruled, as early as the First Dynasty, such as Neithhotep and Meritneith, but there is no definitive proof they ruled in their own right. Another candidate, Nitocris, would have ruled in the Sixth Dynasty; however, there is little proof of her historicity. Some scholars believe the kingship of Nitocris is merely a legend derived from an incorrect translation of Pharaoh Neitiqerty Siptah's name.

Amenemhat IV most likely died without a male heir; consequently, Amenemhat III's daughter, Sobekneferu, assumed the throne as the heir of her father. According to the Turin Canon, she ruled for three years, ten months, and 24 days[4] in the late nineteenth century BC.

Sobekneferu died without an heir and the end of her reign concluded Egypt's Twelfth Dynasty and the Golden Age of the Middle Kingdom. Her death inaugurated the Thirteenth Dynasty.

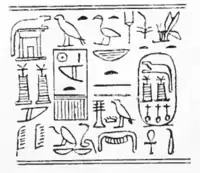

Sobekneferu's name appears on multiple King Lists, namely the Karnak, Saqqara and Turin King Lists, making her the only female Pharaoh to appear on these lists. Later female rulers, namely Hatshepsut, Neferneferuaten and Twosret were all omitted from official King Lists for a number of reasons. Sobekneferu is however absent from the Abydos King List, the only king from the 12th Dynasty who was not included. The reason for this is unknown.

Monuments and tomb

Few monuments have been discovered for Sobekneferu, although many (headless) statues of her have been preserved, including the base of a statue that bears her name and is identified as the representation of a king's royal daughter. It was discovered in Gezer.[6] One statue with her head is known. A bust in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin (Inv. no. 14476), lost in World War II, could be identified as belonging to her, as well. Today, the sculpture is known only from photographic images and plaster casts. It came to the museum in 1899. The head fits on top of the lower part of a royal statue discovered at Semna. The latter can definitely be identified as royal because the royal symbol "unification of the two countries" appears on the side of her throne.[7]

It is known that Sobekneferu made additions to the funerary complex of Amenemhat III at Hawara (called a "labyrinth" by Herodotus) and also, that she built structures at Heracleopolis Magna.

A fine cylinder seal bearing her name and royal titulary is located in the British Museum.[8] A Nile graffito, at the Nubian fortress of Kumma records the Nile inundation height of 1.83 meters in Year 3 of her reign.[9] Another inscription discovered in the Eastern Desert records "year 4, second month of the Season of the Emergence".[10]

Her monumental works consistently associate her with Amenemhat III rather than Amenemhat IV, supporting the theory that she was the royal daughter of Amenemhat III and perhaps, only a stepsister to Amenemhat IV, whose mother was not royal.[6] The Danish Egyptologist, Kim Ryholt, notes that the contemporary sources from her reign show that Sobekneferu never adopted the title of King's Sister-only "King's Daughter", which further supports this hypothesis.[6]

Her tomb has not been identified positively, although Sobekneferu may have been interred in a pyramid complex in Mazghuna that lacks inscriptions. It is immediately north of a similar complex ascribed to Amenemhat IV. A place called Sekhemneferu is mentioned in a papyrus found at Harageh. This might be the name of her pyramid.

See also

References

- Ryholt, Kim S. B., The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c.1800-1550 BCE, Museum Tusculanum Press, Carsten Niebuhr Institute Publications 20, Museum Tusculanum Press (1997), p. 185, ISBN 87-7289-421-0.

- Dodson, Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Egypt, 2004, p. 98.

- Wilkinson, Toby (2010). The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 181, 230. ISBN 978-1-4088-1002-6.

- Ryholt, The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period (1997), p. 15.

- Petrie, Flinders: Scarabs and cylinders with names (1927), available copyright-free here, pl. XIV.

- Ryholt, p. 213.

- Fay, B., R. E. Freed, T. Schelper, F. Seyfried: "Neferusobek Project: Part I", in: G. Miniaci, W. Grajetzki: The World of Middle Kingdom Egypt (2000-1550 BC), Vol. I, London, 2015, ISBN 978-1906137434, pp. 89–91

- Callender, Gae, "The Middle Kingdom Renaissance", in Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford University Press: 2003), paperback, p. 159.

- Callender (203), p. 159.

- Almásy, A., Catalogue of Inscriptions, in U. Luft (ed.), Bi'r Minayh, Report on the Survey 1998-2004, Budapest, 2011, ISBN 978-9639911116, pp. 174–175.

Bibliography

- Dodson, Aidan, and Dyan Hilton. 2004. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, London: Thames & Hudson

- W. Grajetzki, The Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt: History, Archaeology and Society, London: Duckworth, 2006 ISBN 0-7156-3435-6, 61-63

- Shaw, Ian, and Paul Nicholson. 1995. The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers.

- Shaw, Ian, ed. 2000. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press. Graffito ref. p. 170.