Somalis in Sweden

Somalis in Sweden are citizens and residents of Sweden who are of Somali ancestry or are Somali citizens. A large proportion of these emigrated after the civil war in Somalia, with most arriving in Sweden after the year 2006.[2][3] [4]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 70,173 (born in Somalia)[1]

29,524 (born in Sweden to Somali-born parents) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Stockholm, Gothenburg, Malmö | |

| Languages | |

| Somali · Swedish | |

| Religion | |

| Islam |

Demographics

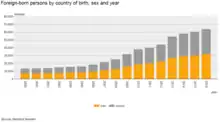

According to Statistics Sweden, Somalis began arriving in Sweden from the late 1980s primarily due to the civil conflict in their country of origin. In 1990, there were just under 1,000 Somalia-born asylum seekers residing in Sweden. This number rose to around 2,000 Somalia-born asylum seekers by 1994, but decreased sharply to close to zero in 2000. As the conflict in Somalia intensified at the turn of the millennium, the number of Somalia-born asylum seekers residing in Sweden increased to a high of just over 5,000 in 2010. That same year, the Swedish government introduced stricter identification document requirements for relatives of earlier migrants, which made it more difficult for Somalia-born individuals and other migrants to obtain a residence permit in Sweden. Consequently, the number of Somalia-born asylum seekers residing in Sweden markedly decreased to slightly over 1,000 in 2014.[6] In 2016, there were 132 registered emigrations from Sweden to Somalia.[7]

A 2007 report on Somalis in Gothenburg found that half of the Somali women in the sample were not living with the fathers of their children, and that only 3 out of 10 young Somalis have passing grades in primary education (Swedish: Grundskola).[8]

According to Statistics Sweden, as of 2016, there are a total 63,853 Somalia-born immigrants living in Sweden.[5] Of those, 41,335 are citizens of Somalia (20,554 men, 20,781 women).[9] Most of the residents are young, primarily belonging to the 15–24 years (8,679 men, 7,728 women), 25–34 years (7,043 men, 7,958 women), and 5–14 years (5,882 men, 5,629 women) age groups.[5] Around 3,000 Somalis inhabit Borlänge.[10] 2,878 Somalia-born individuals also live in Rinkeby-Kista.[11] In 2005, the majority of Somali inhabitants in Gothenburg were concentrated to the Biskopsgården and Bergsjön/Angered area.[12]

In 2013, a Somalia national bandy team was also formed in Borlänge, which participated in the 2014 Bandy World Championship. It is part of the Federation of International Bandy.[10]

Education

In 2010, the governmental Regeringskansliet Statsrådsberedningen bureau estimated that 44% of Somalis in Sweden aged 16–64 were educated to a low level (Förgymnasial), 22% had attained secondary education level (Gymnasial[13]), 9% had attained a post-secondary education level of less than 3 years (Eftergymnasial[13]), and 25% had attained an unknown education level (Okänd[13]).

The Open Society Foundation (OSF) project At Home in Europe counted the proportion of those with a low-level or "unknown" education at 60-70%. The OSF also found that the education level of this group of Somalis made it difficult for them to understand Swedish society and expressions used in the Swedish language.[14]

Over the 2006-2010 period, Somali immigrants to Canada and the United States had higher levels of upper secondary and post-secondary education than Somalis in Sweden, who included a greater proportion of those with "unknown" education level (25%).[15]

According to Statistics Sweden, in 2008-2009, there were 769 pre-school pupils and 7,369 compulsory school pupils who had Somali as their mother tongue.[16] As of 2012-2013, there are 1,011 pre-school pupils and 10,164 compulsory school pupils who have Somali as their mother tongue.[17]

In 2010, there were 4,269 students with Somali as their mother tongue who participated in the state-run Swedish for Immigrants adult language program. Of these pupils, 2,747 had 0–6 years of education in their home country (Antal utbildningsår i hemlandet), 797 had 7–9 years of education in their home country, and 725 had 10 years education or more in their home country.[18] As of 2012, 10,525 pupils with Somali as their mother tongue and 10,355 Somalia-born students were enrolled in the language program.[19]

In 2013, Statistics Sweden found that, of the ten most common countries of origin among persons aged 25–64 who had immigrated to Sweden during the 21st century, 57% of individuals from Somalia were educated to a low level; this was the largest proportion of any of the ten groups.[20]

Employment

In 2005 in Gothenburg, 45% of adult Somalis had zero income from employment, compared to 27% of all born abroad and 10% of those born in Sweden. 7 of 10 Somalis had an income less than 5000 SEK per month (1 euro ~ 10 SEK).[21]

The education level was in 2010 found to be closely correlated with the employment rate since Somalia-born individuals aged 16–64 with a primary and lower secondary education level had an employment rate of around 15%, individuals with an upper secondary education level had an employment rate of roughly 42%, individuals with a post-secondary education level of less than 3 years had an employment rate of about 41%, and individuals with an unknown education level had an employment rate of approximately 3%.[22]

According to a 2011 report by the Herbert Felix Institutet, Somalis tend to reside in Sweden during the non-occupational parts of their lives, when they are in childcare, of school age or in university, or when they are of retirement age and elderly. They instead more commonly spend their occupational years in the United Kingdom and other Anglophone countries, where Somali entrepreneurship is more robust, interconnected and better established.[23]

A 2012 Malmö University report based on Statistics Sweden labor force data indicates that Somalia-born immigrants aged 16–24 had an employment rate of around 7% for males and 6% for females in 1998, which increased to about 13% for males and 16% for females in 2003. Somalia-born immigrants aged 25–54 had an employment rate of approximately 16% for males and 10% for females in 1998, which also rose to roughly 35% for males and 24% for females in 2003. As of 2008, Somalia-born immigrants aged 16–24 have an estimated employment rate of 16% for males and 12% for females, and Somalia-born immigrants aged 25–54 have an estimated employment rate of 35% for males and 25% for females. Additionally, Somalia-born immigrants aged 16–24 had an unemployment rate of around 19% for males and 11% for females in 1998, which decreased to about 14% for males and 7% for females in 2003. Somalia-born immigrants aged 25–54 had an unemployment rate of approximately 43% for males and 20% for females in 1998, which dropped to roughly 24% for males and 13% for females in 2003. As of 2008, Somalia-born immigrants aged 16–24 have an estimated unemployment rate of 15% for males and 10% for females, and Somalia-born immigrants aged 25–54 have an estimated unemployment rate of 28% for males and 21% for females.[24] According to the researchers, the unemployment rates were higher than expected because the Labour Force Surveys on which these figures were based counted individuals that were enrolled in schooling as unemployed.[25]

| Employment [%][2] | Self-employment [%][2] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Somalis | Gap | Total | Somalis | Gap | |

| Sweden 2010 (aged 16–64) | 73 | 21 | 52 | 4.9 | 0.5 | 4.4 |

| USA 2010 (aged 16–64) | 67 | 54 | 13 | 4.3 | 5.1 | -0.8 |

| Canada 2006 (aged 15–65) | 73 | 46 | 27 | 9.2 | 5.3 | 3.9 |

In 2012 SVT reported that four out of five Somali immigrants in Sweden are unemployed, while 70% only have primary education of some form or less.[26]

The governmental Regeringskansliet Statsrådsberedningen bureau in 2012 compared the labor market situation of Somali immigrants in Sweden with other Somali immigrants in Canada and the United States, which identified that Somali workers in North America, although also faced with challenges, generally fared better than their counterparts in Sweden.[27] According to the bureau, since 2000, the employment rate among Somalia-born individuals in Sweden had varied between 20% to 30%. The Somali-owned businesses in North America were also estimated to be 10 times more prevalent than those in Sweden.[28][2]

According to the Regeringskansliet Statsrådsberedningen, these discrepancies in the employment and self-employment rates were due to a number of factors, including a greater proportion of low-educated Somalis in Sweden at compared to those in North America (~70% of Somalis in Sweden were low-educated); a shorter time spent in Sweden compared to North America (around 60% of Somalis residing in Sweden arrived after 2006); easier start-up potential in North America for Somalis who are conversant with the English language; greater trust in, facility with, and incentives to establishing businesses in the free market-based system of North America than in the government-centered public system of Sweden; an entrenched unemployment crisis in Sweden during the late 20th century; and easier access to simple jobs for new arrivals in the North American labor market than in the Swedish labor market due to lower minimum wages and less employment protection.[2]

| Sweden labor market

(Somalis aged 15–64, in percentages) |

2014[7][29] |

|---|---|

| Employment | 33 |

| Employment Population Ratio | 22 |

| Unemployment | 25 |

According to Statistics Sweden, as of 2014, Somalia-born immigrants aged 25–64 in Sweden have an employment rate of approximately 33%. The share of employment among these foreign-born individuals varies according to education level, with employment rates of around 23% (32% males, 16% females) among Somalia-born individuals who have attained a primary and lower secondary education level (16,010 individuals), 51% (51% males, 50% females) among those who have attained an upper secondary education level (8,115 individuals), 51% (51% males, 49% females) among those who have attained a post-secondary education level of less than 3 years (1,937 individuals), and 61% (60% males, 63% females) among those who have attained a post-secondary education level of more than 3 years (1,517 individuals).[30]

As of 2014, according to the Institute of Labor Economics, Somalia-born residents in Sweden have an employment-population ratio of about 22%. They also have an unemployment rate of approximately 25%.[29]

Community

When Somalis go to Sweden, they enter a country which has not experienced a major war in over two hundred years, a state apparatus stretching over a five-century time span, strong institutions, high-tech industry, an advanced knowledge-based economy with a generally high level of education. Sweden is also one of the most secularized societies with liberal values in areas that are central to traditional Somali culture: family, sexuality and gender. These circumstances combine to make a society which is radically different from that of Somalia.[31]

According to an official report in 1999, most Somalis in Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö lived in multicultural neighbourhoods where few Swedes and Swedish-speakers lived, this also applied to Somalis in smaller towns. A contributing factor to this development was that these were the districts where mosques were located where they could practice Islam and that Somali community organisations were established in these districts.[32]

According to an interview study done by Malmö University in 2013, Somalis express strong concerns about losing their culture and Islamic religion. Adult Somalis stated their greatest worry was to ensure a Somali identity among their children, which led to endless conflicts with daycare institutions and schools who "ignore their cultural preferences and teach children things which are the exact opposite of what their parents preach".[31]

Clans

Somali clan culture is preserved into exile for two predominant reasons:[33] the first is that every individual is a product of his upbringing and processes for change can be lengthy and difficult. The second that technical developments have enabled easy communication with relatives in the home country both with telecommunications and cheap flights to Somalia.[31]

Somali clan culture plays an important role in new host countries for the Somali diaspora and new arrivals join already established social environments. The clan system also serves as an arena for sharing information which is crucial for making decisions about whether to move to other countries. The clan system also facilitates money transactions to relatives who live in the Horn of Africa, via a form of banking where no receipts are used.[3] Relatives in Somalia are often dependent upon remittance from their relatives in exile, who in turn struggle economically due to their contributions.[31]

Somali settlement patterns follow clan lines in Gothenburg, where Hjällbo and Hammarkullen districts are dominated by the Darod clan, Hawiye clan members are mostly found in Hisingen and the Isaaq clan in the Frölunda district.[34]

Community organisations

Somalis residing in Sweden have established various organisations to serve their community. Except for the multi-clan Somalilandföreningen, the Somali community associations are generally based on clan affiliation, although a few individuals from different clans can also be found in the Somaliska kulturföreningen and other larger organisations.[35]

In 2015-16, Somaliska riksförbundet i Sverige (SRFS) community organisation was granted funding from the governmental Swedish Inheritance Fund for the Navigator project, which, through seminars and workshops, aims to counteract extremism and prevent religiously-inspired violence and potential terrorist recruitment.[36][37] As of 2016, there are around 100 Somali community organizations in Sweden according to the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.[38] Several of them receive state funding from the Swedish Agency for Youth and Civil Society, including the Somaliska riksförbundet i Sverige, Somaliland riksförbund i Sverige, Riksföreningen för khaatumo state of Somalia, Somaliska ungdomsföreningen i Sverige, Barahley somaliska förening, Somali Dialogue Center and Somalilands förening.[39]

According to the Herbert Felix Institutet, as of 2011, the three principal active Somali community organisations based in the Scania region are the Somalilandföreningen and the Hiddo Iyo Dhaqan in Malmö, as well as the Somaliska kulturföreningen in Kristianstad. The Somalilandföreningen has around 500 members primarily hailing from the Somaliland region in northwestern Somalia, the Hiddo Iyo Dhaqan has a few hundred members mainly from southern Somalia, and the Somaliska kulturföreningen has about 100 members. Many other smaller associations have been established in the region, but these do not operate regularly and are essentially single person organisations ("one man show").[35]

According to the Herbert Felix Institutet, a number of European Union-funded projects have been launched around Scania in conjunction with the Somali community organisations. Among these endeavours are the Somalier startar företag, which helps Somali entrepreneurs establish companies; Integration på arbetsmarknaden för somalier FIAS, which assists in labor market integration in the Eskilstuna municipality; Integration genom arbete, which facilitates labor market integration in and near the Åstorp Municipality; Partnerskap Skåne, which is centered on developmental work; Samhälls-och hälsokommunikatör, which provides customized and interactive cultural information; Integration i förening, which assists newcomers by connecting them with and offering information on the local business community; Ökad inkludering genom språk, which in conjunction with industry leaders helps with language acquisition through vocational education; Bazar, Integration och Arbetsmarknad, Malmö Stad, which explores the possibilities and obstacles for establishing an entrepreneurial bazaar in the Malmö, Gothenburg, Västerås, Södertälje and Eskilstuna municipalities; and Uppstart Malmö, which liaises job-creating entrepreneurs with experienced investors in Malmö and provides interest-free loans and free financial guidance.[40]

Notable individuals

- Farhiya Abdi, basketball player

- Amun Abdullahi, journalist

- Ferid Ali, football player

- Cherrie, stage name of singer Shiriihan Mohamed Abdulle

- Dree Low, stage name of Salah Abdi Abdulle, rap musician

- Rizak Dirshe, middle distance runner

- Bilal Hussein, football player

- Mohamoud Jama and Bille Ilias Mohamed, jihadists

- Ali Yassin Mohamed, militant Islamist

- Mustafa Mohamed, long distance runner

- Bilan Osman, journalist and author

- Abdirizak Waberi, politician and Islamic organization leader

- Mona Walter, Islam-critical social commentator

References

- "Population by country of birth, age and sex. Year 2000 - 2019". Statistikdatabasen. Retrieved 2020-06-21.

- Carlson, Magnusson & Rönnqvist (2012). Somalier på arbetsmarknaden - har Sverige något att lära? : underlagsrapport 2 till Framtidskommissionen. Stockholm: Regeringskansliet - Fritzes. pp. 13–16. ISBN 978-91-38-23810-3. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- Johnsdotter, Sara (October 2010). Somaliska föreningar som överbryggare (PDF). Hälsa och samhälle, Malmö University. pp. 5, 13. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- Mångfaldsbarometern 2014 (PDF). Gävle University College. 2014. p. 57.

- "Foreign-born persons by country of birth, age, sex and year". Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- "Sveriges framtida befolkning 2015–2060 - The future population of Sweden 2015–2060" (PDF). Statistics Sweden. pp. 98, 99, 102, 104. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Immigrations and emigrations by country of emi-/immigration, observations and year". Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- "28/10 -07: Göteborgs somalier - ett folk i kris". Göteborgs-Posten (in Swedish). Retrieved 2018-08-01.

Jag har inte stött på så grov våldsbrottslighet tidigare. Vanligtvis trappas våldet upp efter hand som gärningsmännen begår flera brott, men i många av de här fallen har man gått in med kniven direkt och redan i unga år.

- "Foreign citizens by country of citizenship, sex and year". Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- "Swede to coach first Somalia bandy team". Radio Sweden. 13 May 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- "Welcome to Rinkeby-kista" (PDF). City District Council. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- "28/10 -07: Göteborgs somalier - ett folk i kris". Göteborgs-Posten (in Swedish). Retrieved 2018-04-01.

- "Statistisk årsbok 2014" (PDF). Statistics Sweden. pp. 448–449. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Somalier i Malmö - At Home in Europe Project (PDF). Open Society Foundations. 2014. p. 2.

- Carlson, Magnusson & Rönnqvist (2012). Somalier på arbetsmarknaden - har Sverige något att lära? : underlagsrapport 2 till Framtidskommissionen. Stockholm: Regeringskansliet - Fritzes. p. 42. ISBN 978-91-38-23810-3. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- "Statistisk årsbok för Sverige - Statistical Yearbook of Sweden 2010" (PDF). Statistics Sweden. pp. 505, 510. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- "Statistisk årsbok för Sverige - Statistical Yearbook of Sweden 2014" (PDF). Statistics Sweden. pp. 452, 455. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- centralbyrån, SCB - Statistiska (2010). Statistical Yearbook of Sweden 2010 (PDF). [S.l.]: Statistiska Centralbyran. p. 198. ISBN 9789161814961. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- "Utbildning och forskning - Statistisk årsbok 2014" (PDF). Statistics Sweden. p. 456. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- "Hög utbildning bland 2000-talets invandrare". Statistiska Centralbyrån (in Swedish). 3 Mar 2015. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

Många invandrare från Somalia och Thailand har kort utbildning[...] Utbildningsnivå 2013 för utrikes födda från de tio vanligaste födelseländerna. Personer i åldern 25–64 år som invandrat under 2000-talet[...] De personer som invandrat från Somalia och Thailand under 2000-talet har i stor utsträckning en förgymnasial utbildning som högsta utbildning, 57 respektive 46 procent.

- "28/10 -07: Göteborgs somalier - ett folk i kris". Göteborgs-Posten (in Swedish). Retrieved 2018-04-01.

- Carlson, Magnusson & Rönnqvist (2012). Somalier på arbetsmarknaden - har Sverige något att lära? : underlagsrapport 2 till Framtidskommissionen. Stockholm: Regeringskansliet - Fritzes. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-91-38-23810-3. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- Sandberg, P (2011). "Somaliskt informations- och kunskapscenter i Skåne" (PDF). Herbert Felix Institutet. pp. 6–7.

Den somaliska diasporan i flera anglosaxiska länder är känd för sitt entreprenörskap, sina internationella nätverk världen över, tillit inom gruppen vid affärsuppgörelser där kontrakt sker endast muntligt, en stor flyttbenägenhet världen över samt stort risktagande vid företagande. I stort sett samtliga som intervjuades kände mer samhörighet med Sverige än Storbritannien och många längtade tillbaka. Men samtidigt såg de sig oerhört begränsade i Sverige. Vi noterade att många bor i Sverige den tid då de inte är yrkesverksamma, d.v.s. då de befinner sig i barnomsorgen, grundskolan, gymnasieskolan, universitetet eller då de är äldre för pension och sjukvård. Den yrkesverksamma delen av sitt liv är de istället bosatta i Storbritannien. Intervjumaterialet kommer att sammanställas och presenteras i Almedalen 4 juli.

- Pieter Bevelander and Inge Dahlstedt. "Sweden's Population Groups Originating from Developing Countries: Change and Integration" (PDF). Malmö University. pp. 51–61. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- Pieter Bevelander and Inge Dahlstedt. "Sweden's Population Groups Originating from Developing Countries: Change and Integration" (PDF). Malmö University. p. 58. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

we use register data to calculate our indicators. For the indicator unemployment this means that an individual can only be in one state, e.g. employed, enrolled in education (see Chapter 4), unemployed or inactive. Regularly published unemployment figures are based on Labour Force Surveys in which the informant can be both enrolled in education and unemployed, and due to this have higher unemployment rates.

- Nyheter, SVT. "Bara var femte somalier har jobb i Sverige". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 2017-09-14.

- Carlson, Magnusson & Rönnqvist (2012). Somalier på arbetsmarknaden - har Sverige något att lära? : underlagsrapport 2 till Framtidskommissionen. Stockholm: Regeringskansliet - Fritzes. p. 13. ISBN 978-91-38-23810-3. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

Denna rapport har utarbetats på uppdrag av regeringens framtidskommission och haft att besvara fem frågor: Hur är arbetsmarknadssituationen för somalier i Sverige? Varför går det så dåligt för dem här? Varför går det bättre för dem i ett urval av jämförbara länder som Storbritannien, Kanada och USA? Går det att dra några slutsatser för framtiden av detta och kan andra invandrargrupper möta samma problem i Sverige? Vilka policyrekommendationer bör följa av detta?

- Carlson, Magnusson & Rönnqvist (2012). Somalier på arbetsmarknaden - har Sverige något att lära? : underlagsrapport 2 till Framtidskommissionen. Stockholm: Regeringskansliet - Fritzes. p. 14. ISBN 978-91-38-23810-3. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

Av kapitel 2 framgår att andelen sysselsatta med födelseland Somalia sedan sekelskiftet 2000 pendlat mellan 20 och 30 procent[...] Deras företagande är omkring tio gånger kraftigare där än här.

- "Mapping Diasporas in the European Union and the United States - Comparative analysis and recommendations for engagement" (PDF). Institute of Labor Economics. Retrieved 20 October 2017. - cf. Appendix 4: Diaspora characteristics - labour force indicators by sending countries

- "Befolkningens utbildning och sysselsättning 2014 - Educational attainment and employment of the population 2014" (PDF). Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- Brinkemo, Per. Mellan klan och stat : somalier i Sverige. ISBN 978-91-7703-217-5. OCLC 1140682924.

- Delaktighet för integration – att stimulera integrationsprocessen för somalisktalande i Sverige. Integrationsverkets rapportserie 1999:4. Integrationsverket. 1999.

- Lewis, I. M. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. pp. 11–14. ISBN 0852552807. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Larsson, Göran, 1970- (2014). Islam och muslimer i Sverige : en kunskapsöversikt. Sverige. Nämnden för statligt stöd till trossamfund. Bromma: Nämnden för statligt stöd till trossamfund. p. 115. ISBN 978-91-980611-6-1. OCLC 941538793.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Sandberg, P (2011). "Somaliskt informations- och kunskapscenter i Skåne" (PDF). Herbert Felix Institutet. p. 7.

Sammanhållningen i den somaliska diasporan i Skåne är inte oproblematisk. Ett stort antal somaliska föreningar har startats runtom i regionen som kallas för "enmansshows" av de flesta somalier jag träffat.[...] Alla somaliska föreningar utom Somalilandföreningen i Malmö är baserade på klantillhörighet (även om det finns ett fåtal personer från andra klaner i de större föreningarna som t.ex. Somaliska kulturföreningen i Kristianstad). Det blir minst sagt en spretig och rörig bild över vilka personer ska anses vara företrädare för somalierna. Det som tidigare påvisats under förberedelsearbetet är att somalier är en oerhört heterogen grupp där klantillhörighet och släktskapsband dominerar. Kartläggningen har visat att endast tre föreningar har en reguljär verksamhet som kan anses av större vikt och som kan ha en betydelse för det framtida somaliska informations- och kunskapscentrat. Somalilandföreningen, Malmö: Fungerar redan idag som en klanöverskridande organisation, dock med koncentration av personer från Somaliland i nordvästra Somalia. Somalilandföreningen med ca 500 medlemmar har en omfattande verksamhet i dagsläget. Hiddo Iyo Dhaqan, Malmö: Har en hel del främst ungdomsverksamhet och består i dagsläget av ett par hundra personer. De flesta härstammar från södra Somalia. Somaliska kulturföreningen, Kristianstad: Har ca 100 medlemmar enligt egna uppgifter och begränsad aktivitet. I dagsläget pågår interna konflikter i föreningen vilket paralyserat dess handlingskraft.

- "Ekonomiskt stöd & slutrapporter - 2015". www.bra.se (in Swedish). 2015. Retrieved 2017-11-11.

Somaliska Riksförbundet i Sverige (SRFS) har beviljats finansiering från Allmänna Arvsfonden (AA) för projektet Navigator. Projektet syftar till att förebygga religiöst inspirerad våldsbejakande extremism samt sprida kunskap för att avvärja eventuell rekrytering till terrorverksamheter. Dessutom vill SRFS bryta den tystnadskultur som finns runt problemet genom att anordna seminarier för ungdomar och föräldrar, besöka skolor och samarbeta med andra somaliska föreningar. Beslutet avser en utvärdering av hur väl de uppsatta målen har nåtts och hur effektivt aktiviteterna har genomförts. I utvärderingen ingår också en granskning av om rutiner och genomförande fungerar bra eller behöver förändras för att uppnå de uppsatta målen.

- "Navigator - fredsbejakande unga vuxna somalier | Arvsfonden". www.arvsfonden.se (in Swedish). 20 August 2016. Retrieved 2017-11-11.

Projektets syfte är att förebygga våldsbejakande extremism och extremismmiljöer.

- "Sida lanserar svensk-somaliskt företagarprogram". www.sida.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 2017-11-10.

I Sverige finns ett hundratal civilsamhällesorganisationer med somalisk anknytning.

- "Vi har fått bidrag - Organisationsbidrag, Projektbidrag, EU-bidrag | MUCF". www.mucf.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 2017-11-10.

- Sandberg, P (2011). "Somaliskt informations- och kunskapscenter i Skåne" (PDF). Herbert Felix Institutet. pp. 5–6.