Malmö

Malmö (/ˈmælmoʊ, ˈmɑːlmɜː/;[4][5][6] Swedish: [ˈmâlmøː] (![]() listen); Danish: Malmø [ˈmælmˌøˀ]) is the largest city in the Swedish county (län) of Skåne. It is the third-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm and Gothenburg, and the sixth-largest city in Scandinavia, with a population of 316,588 (municipal total 338,230 in 2018).[7] The Malmö Metropolitan Region is home to over 700,000 people,[8] and the Öresund region, which includes Malmö, is home to 4 million people.[9]

listen); Danish: Malmø [ˈmælmˌøˀ]) is the largest city in the Swedish county (län) of Skåne. It is the third-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm and Gothenburg, and the sixth-largest city in Scandinavia, with a population of 316,588 (municipal total 338,230 in 2018).[7] The Malmö Metropolitan Region is home to over 700,000 people,[8] and the Öresund region, which includes Malmö, is home to 4 million people.[9]

Malmö | |

|---|---|

From top left to right: Malmö Live, Turning Torso, Emporia, Griffin Sculpture, Lönngården 1950s apartments, and the Öresund Bridge | |

Coat of arms | |

| Motto(s): Mångfald, Möten, Möjligheter (Eng.: Diversity, Meetings, Possibilities) | |

Malmö Location within Skåne County  Malmö Location within Sweden | |

| Coordinates: 55°36′21″N 13°02′09″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| County | Skåne County |

| Municipality | Malmö Municipality and Burlöv Municipality |

| Charter | 13th century |

| Government | |

| • Chair of the City Administration | Katrin Stjernfeldt Jammeh (Social Democrats) |

| Area | |

| • City | 332.6 km2 (128.4 sq mi) |

| • Land | 156.9 km2 (60.6 sq mi) |

| • Water | 175.8 km2 (67.9 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,522 km2 (974 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 12 m (39 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2019)[2] | |

| • City | 344,166 |

| • Density | 4,049/km2 (10,490/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 740,840[3] |

| Demonym(s) | Malmöit |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 2xx xx |

| Area code(s) | (+46) 40 |

| Website | www |

Malmö was one of the earliest and most industrialised towns in Scandinavia, but it struggled to adapt to post-industrialism. Since the 2000 completion of the Öresund Bridge, Malmö has undergone a major transformation, producing new architectural developments, supporting new biotech and IT companies, and attracting students through Malmö University and other higher education facilities. Over time, Malmö's demographics have changed and by the turn of the 2020's almost half the municipal population had a foreign background.[10] The city contains many historic buildings and parks, and is also a commercial center for the western part of Skåne County. It is also home to Malmö FF, the Swedish football club with the most national championships and the only Nordic club to have reached the European Cup final.

Malmö has a very mild climate for the latitude and normally remains above freezing in winter, with prolonged snow cover being rare.

History

The earliest written mention of Malmö as a city dates from 1275.[11] It is thought to have been founded shortly before that date,[11] as a fortified quay or ferry berth of the Archbishop of Lund,[12] some 20 kilometres (12 miles) to the north-east. Malmö was for centuries Denmark's second-biggest city. Its original name was Malmhaug (with alternate spellings), meaning "Gravel pile" or "Ore Hill". An alternate story stems from a more gruesome tale that suggests that a maiden was once ground up in a mill on what is now the town square. The name would originate from 'Mal Mö', which translates to 'Ground up maiden.' A millstone that was placed in 1538 can still be found on the town square today.[13][14][15]

In the 15th century, Malmö became one of Denmark's largest and most visited cities, reaching a population of approximately 5,000 inhabitants. It became the most important city around the Øresund, with the German Hanseatic League frequenting it as a marketplace, and was notable for its flourishing herring fishery. In 1437, King Eric of Pomerania (King of Denmark from 1396 to 1439) granted the city's arms: argent with a griffin gules, based on Eric's arms from Pomerania. The griffin's head as a symbol of Malmö extended to the entire province of Skåne from 1660.

In 1434, a new citadel was constructed at the beach south of the town. This fortress, known today as Malmöhus, did not take its current form until the mid-16th century. Several other fortifications were constructed, making Malmö Sweden's most fortified city, but only Malmöhus remains.

Lutheran teachings spread during the 16th century Protestant Reformation, and Malmö became one of the first cities in Scandinavia to fully convert (1527–1529) to this Protestant denomination.

In the 17th century, Malmö and the Skåneland region came under control of Sweden following the Treaty of Roskilde with Denmark, signed in 1658. Fighting continued, however; in June 1677, 14,000 Danish troops laid siege to Malmö for a month, but were unable to defeat the Swedish troops holding it.

By the dawn of the 18th century, Malmö had about 2,300 inhabitants. However, owing to the wars of Charles XII of Sweden (reigned 1697–1718) and to bubonic plague epidemics, the population dropped to 1,500 by 1727. The population did not grow much until the modern harbor was constructed in 1775. The city started to expand and the population in 1800 was 4,000. 15 years later, it had increased to 6,000.[16]

In 1840, Frans Henrik Kockum founded the workshop from which the Kockums shipyard eventually developed as one of the largest shipyards in the world. The Southern Main Line was built between 1856 and 1864; this enabled Malmö to become a center of manufacture, with major textile and mechanical industries. In 1870, Malmö overtook Norrköping to become Sweden's third-most populous city, and by 1900 Malmö had strengthened this position with 60,000 inhabitants. Malmö continued to grow through the first half of the 20th century. The population had swiftly increased to 100,000 by 1915 and to 200,000 by 1952.

1900–1969

In 1914 (15 May to 4 October) Malmö hosted the Baltic Exhibition. The large park Pildammsparken was arranged and planted for this large event. The Russian part of the exhibition was never taken down, owing to the outbreak of World War I.

On 18 and 19 December 1914, the Three Kings Meeting was held in Malmö. After a somewhat infected period (1905–1914), which included the dissolution of the Swedish-Norwegian Union, King Oscar II was replaced with King Håkon VII in Norway, who was the younger brother of the Danish King Christian X. As Oscar died in 1907, and his son Gustav V became the new King of Sweden, the tensions within Scandinavia were still unclear, but during this historical meeting, the Scandinavian Kings found internal understanding, as well as a common line about remaining neutral in the ongoing war.

Within sports, Malmö has mostly been associated with football. IFK Malmö participated in the first ever edition of Allsvenskan 1924/25, but from the mid-1940s Malmö FF started to rise, and ever since it has been one of the most prominent clubs within Swedish football. They have won Allsvenskan 23 times in all (as of February 2018) between 1943/44 and 2017.

1970s and later

By 1971, Malmö reached 265,000 inhabitants, but this was the peak which would stand for more than 30 years. (Svedala was, for a few years in the early 1970s, a part of Malmö municipality.)

By the mid-1970s Sweden experienced a recession that hit the industrial sector especially hard; shipyards and manufacturing industries suffered, which led to high unemployment in many cities of Skåne. Kockums shipyard had become a symbol of Malmö as its largest employer and, when shipbuilding ceased in 1986, confidence in the future of Malmö plummeted among politicians and the public. In addition, many middle-class families moved into one-family houses in surrounding municipalities such as Vellinge Municipality, Lomma Municipality and Staffanstorp Municipality, which profiled themselves as the suburbs of the upper-middle class. By 1985, Malmö had lost 35,000 inhabitants and was down to 229,000.

The Swedish financial crises of the early 1990s exacerbated Malmö's decline as an industrial city; between 1990 and 1995 Malmö lost about 27,000 jobs and its economy was seriously strained. However, from 1994 under the leadership of the then mayor Ilmar Reepalu, the city of Malmö started to create a new economy as a center of culture and knowledge. Malmö reached bottom in 1995, but that same year marked the commencement of the massive Öresund Bridge road, railway and tunnel project, connecting it to Copenhagen and to the rail lines of Europe. The new Malmö University opened in 1998 on Kockums' former dockside. Further redevelopment of the now disused south-western harbor followed; a city architecture exposition (Bo01) was held in the area in 2001, and its buildings and villas form the core of a new city district. Designed with attractive waterfront vistas, it was intended to be and has been successful in attracting the urban middle-class.

Since 1974, the Kockums Crane had been a landmark in Malmö and a symbol of the city's manufacturing industry, but in 2002 it was disassembled and moved to South Korea. In 2005, Malmö gained a new landmark with completion of Turning Torso, the tallest skyscraper in Scandinavia. Although the transformation from a city with its economic base in manufacturing has returned growth to Malmö, the new types of jobs have largely benefited the middle and upper classes.

In its 2015 and 2017 reports, Police in Sweden placed the Rosengård and the Södra Sofielund/Seved district in the most severe category of urban areas with high crime rates.[17][18]

Geography

Malmö is located at 13°00' east and 55°35' north, near the southwestern tip of Sweden, in Skåne County.

The city is part of the transnational Öresund Region and, since 2000, has been linked by the Öresund Bridge across the Öresund to Copenhagen, Denmark. The bridge opened on 1 July 2000, and measures 8 kilometres (5 miles) (the whole link totalling 16 km), with pylons reaching 204.5 metres (670.9 feet) vertically. Apart from the Helsingborg-Helsingør ferry links further north, most ferry connections have been discontinued.

Climate

Malmö, like the rest of southern Sweden, has an oceanic climate (Cfb). Despite its northern location, the climate is mild compared to other locations at similar latitudes, mainly because of the influence of the Gulf Stream and also its westerly position on the Eurasian landmass. Owing to its northern latitude, daylight lasts 17 hours 31 minutes in midsummer, but only around seven hours in midwinter. According to data from 2002–2014 Falsterbo, to the south of the city, received an annual average of 1,895 hours of sunshine while Lund, to the north, received 1,803 hours. The sunshine data in the weather box is based on the data for Falsterbo.[19]

Summers are mild with average high temperatures of 20 to 23 °C (68 to 73 °F) and lows of around 11 to 13 °C (52 to 55 °F). Heat waves during the summer arise occasionally. Winters are fairly cold and windy, with temperatures steady between −3 to 4 °C (27 to 39 °F), but it rarely drops below −10 °C (14 °F).

Rainfall is light to moderate throughout the year with 169 wet days. Snowfall occurs mainly in December through March, but snow covers do not remain for a long time,[20] and some winters are virtually free of snow.

| Climate data for Malmö, 2002–2018; extremes since 1901 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) |

12.5 (54.5) |

19.5 (67.1) |

26.2 (79.2) |

29.6 (85.3) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.6 (92.5) |

28.0 (82.4) |

22.8 (73.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 8.0 (46.4) |

7.7 (45.9) |

13.8 (56.8) |

19.2 (66.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

26.9 (80.4) |

29.2 (84.6) |

28.2 (82.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

9.2 (48.6) |

29.9 (85.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

6.7 (44.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

17.6 (63.7) |

20.5 (68.9) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.3 (72.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

12.6 (54.7) |

8.0 (46.4) |

4.8 (40.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.8 (33.4) |

0.8 (33.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

12.7 (54.9) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.7 (58.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

5.8 (42.4) |

2.8 (37.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.4 (29.5) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

0.0 (32.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

6.4 (43.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

0.7 (33.3) |

5.7 (42.3) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −11.1 (12.0) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

1.0 (33.8) |

5.8 (42.4) |

9.4 (48.9) |

8.0 (46.4) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−7.7 (18.1) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −28.0 (−18.4) |

−23.1 (−9.6) |

−23.3 (−9.9) |

−12.1 (10.2) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

−22.2 (−8.0) |

−28.0 (−18.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58.0 (2.28) |

39.7 (1.56) |

38.5 (1.52) |

30.0 (1.18) |

39.9 (1.57) |

67.3 (2.65) |

71.1 (2.80) |

86.3 (3.40) |

42.3 (1.67) |

66.7 (2.63) |

64.2 (2.53) |

69.4 (2.73) |

673.2 (26.50) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 43.6 | 64.4 | 138.9 | 222.9 | 274.4 | 271.5 | 272.1 | 236.0 | 188.1 | 115.9 | 56.8 | 33.1 | 1,917.7 |

| Source 1: SMHI Open Data[21] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: SMHI Average Data 2002–2018[22] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Malmö 2014-2020 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4.0 (39.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.9 (64.2) |

21.4 (70.5) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.8 (73.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

13.3 (55.9) |

8.6 (47.5) |

6.0 (42.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

4.3 (39.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

16.9 (62.4) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

10.3 (50.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

4.4 (39.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

0.1 (32.2) |

0.9 (33.6) |

3.8 (38.8) |

8.1 (46.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

11.3 (52.3) |

7.5 (45.5) |

4.4 (39.9) |

2.1 (35.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Source 1: SMHI Open Data[23] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: SMHI Average Data 2002–2018[24] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Malmö | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C | 4.0 |

2.9 |

3.5 |

6.2 |

10.9 |

15.7 |

18.2 |

18.7 |

16.3 |

12.8 |

9.3 |

6.0 |

10.4 |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 8.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 14.0 | 16.0 | 17.0 | 16.0 | 15.0 | 13.0 | 11.0 | 9.0 | 7.0 | 12.4 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Source: Weather Atlas[25] | |||||||||||||

Transport

Öresund Line trains cross the Öresund Bridge every 20 minutes (hourly late night) connecting Malmö to Copenhagen, and the Copenhagen Airport. The trip takes around 35–40 minutes. Additionally, some of the X 2000 and Intercity trains to Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Kalmar cross the bridge, stopping at Copenhagen Airport. In March 2005, excavation began on a new railway connection called the City Tunnel, which opened for traffic on 4 December 2010. The tunnel runs south from Malmö Central Station through an underground station at the Triangeln railway station to Hyllievång (Hyllie Meadow). Then, the line comes to the surface to enter Hyllie Station, also created as part of the tunnel project. From Hyllie Station, the line connects to the existing Öresund line in either direction, with the Öresund Bridge lying due west.

Besides the Copenhagen Airport, Malmö has an airport of its own, Malmö Airport, today chiefly used for domestic Swedish destinations, charter flights and low-cost carriers.

The motorway system has been incorporated with the Öresund Bridge; the European route E20 goes over the bridge and then, together with the European route E6 follows the Swedish west coast from Malmö–Helsingborg to Gothenburg. E6 goes further north along the west coast and through Norway to the Norwegian town Kirkenes at Barents Sea. The European route to Jönköping–Stockholm (E4) starts at Helsingborg. Main roads in the directions of Växjö–Kalmar, Kristianstad–Karlskrona, Ystad (E65), and Trelleborg start as freeways.

Malmö has 410 kilometres (250 mi) of bike paths; approximately 40% of all commuting is done by bicycle.

Ports

The city has two industrial harbors; one is still in active use and is the largest Nordic port for car importation.[26] It also has two marinas: the publicly owned Limhamn Marina (55°35′N 12°55′E) and the private Lagunen (55°35′N 12°56′E), both offering a limited number of guest docks.

Public transport consisted of a tram network from 1887 until 1973. Afterwards, it was replaced by a bus network.

Malmö S-Train

A local train line with circular traffic at seven stations was opened in December 2018. The stations are Malmö Central Station (underground platforms) – Triangeln station – Hyllie station – Malmö South/Svågertorp – Persborg – Rosengård – Östervärn – Malmö Central Station (main overground terminus). Some trains arrive from Kristianstad and finish with a lap around Malmö, whilst other trains at this circular line, never drive outside the city limits. There is at least a 30 minutes service between each departure, but far more between the Central Station and Hyllie. Extension plans of a minor network system exists.[27][28]

Proposed metro

The Öresundsmetro is a proposed rapid transit network linking Malmö with the existing Copenhagen Metro through a 22 km tunnel under the Öresund.[29]

Municipality

Malmö Municipality is an administrative unit defined by geographical borders, consisting of the City of Malmö[30] and its immediate surroundings.

Malmö (Malmö tätort) consists of the urban part of the municipality together with the small town of Arlöv in the Burlöv Municipality. Both municipalities also include smaller urban areas and rural areas, such as the suburbs of Oxie and Åkarp. Malmö tätort is to be distinguished from Malmö stad (the city of Malmö), which is a semi-official name of Malmö Municipality.

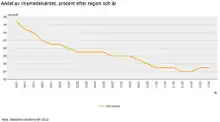

The leaders in Malmö created a commission for a socially sustainable Malmö in November 2010. The commissions were tasked with providing evidence-based strategies for reducing health inequalities and improve living conditions for all citizens of Malmö, especially for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged and issued its final report in December 2013.[31]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 198,856 | — |

| 1960 | 234,453 | +17.9% |

| 1970 | 265,505 | +13.2% |

| 1980 | 233,803 | −11.9% |

| 1990 | 233,887 | +0.0% |

| 2000 | 259,579 | +11.0% |

| 2010 | 298,963 | +15.2% |

| 2015 | 320,147 | +7.1% |

| Note: Svedala municipality was included in Malmö municipality during the large municipality reforms in Sweden, which occurred from the late 1960s until 1974, but Svedala soon became a new municipality of its own, which explains a good part of the decreased population between 1970 and 1980. (Statistics for the municipality)[32][33] | ||

Malmö has a young population by Swedish standards, with almost half of the population under the age of 35 (48.2%).[34]

After 1971, Malmö had 265,000 inhabitants, but the population then dropped to 229,000 by 1985.[35] The total population of the urban area was 280,415 in December 2010. It then began to rise again, and had passed the previous record by the 1 January 2003 census, when it had 265,481 inhabitants.[36] On 27 April 2011, the population of Malmö reached the 300,000 mark.[37] In 2017 the total population of the city was 316,588 inhabitants out of a municipal total of 338,230.[7]

In 2019, approximately 55.5% of the population of Malmö municipality (190,849 residents) had at least one parent born abroad.[38] The Middle East, Horn of Africa, former Yugoslavia and Denmark are the main sources of immigration.[39][40] In addition, 14.8% (50 999 residents) of the population in 2019 were foreign nationals.[41]

Foreign-born population by country, 31 December 2018:

| 11,790 | |

| 7,721 | |

| 7,446 | |

| 7,440 | |

| 6,912 | |

| 6,403 | |

| 4,061 | |

| 4,004 | |

| 2,463 | |

| 2,422 | |

| 2,033 | |

| 1,559 | |

Greater Malmö is one of Sweden's three officially recognized metropolitan areas (storstadsområden) and since 2005 is defined as the municipality of Malmö and 11 other municipalities in the southwestern corner of Skåne County.[42] As of 2019, its population was recorded as 740,840.[43] The region covers an area of 2,522 square kilometres (974 sq mi).[1] The municipalities included, apart from Malmö, are Burlöv, Eslöv, Höör, Kävlinge, Lomma, Lund, Skurup, Staffanstorp, Svedala, Trelleborg and Vellinge. Together with Lund, Malmö is the region's economic and education hub.

Economy

The economy of Malmö was traditionally based on shipbuilding (Kockums) and construction-related industries, such as concrete factories. The region's leading university, along with its associated hi-tech and pharmaceutical industries, is located in Lund about 16 kilometres (10 miles) to the north-east.

Malmö had a troubled economic situation following the mid-1970s. Between 1990–1995, 27,000 jobs were lost, and the budget deficit was more than one billion Swedish krona (SEK). In 1995, Malmö had Sweden's highest unemployment rate.[44]

However, during the last two decades, there has been a revival. One contributing factor has been the economic integration with Denmark brought about by the Öresund Bridge, which opened in July 2000. Also the university founded in 1998 and the effects of integration into the European Union have contributed. In 2017 the unemployment rate is still high but Malmö has, in the last 20 years, had one of the strongest employment growth rates in Sweden. But a lot of those jobs are taken by workers outside the neighboring municipalities.[45]

As of 2016, the largest companies were:[46]

- Skanska – heavy construction

- Nobina – transport

- PostNord – postal services

- Pågen – bakery

- IKEA – furniture

Almost 30 companies have moved their headquarters to Malmö during the last seven years, generating around 2,300 jobs. Among them are IKEA who has most of its headquarter functions based in Malmö.[47]

The number of start-up companies is high in Malmö. Around 7 new companies are started every day in Malmö. In 2010, the renewal of the number of companies amounted to 13.9%, which exceeds both Stockholm and Gothenburg. Especially strong growth is in the gaming area with Massive entertainment and King being the flagship companies for the industry. Among the industries that continue to increase their share of companies in Malmö are transport, financial and business services, entertainment, leisure and construction.[48]

Education

Malmö has the country's ninth-largest school of higher education, Malmö University, established in 1998. It has 1,600 employees and 24,000 students (2014).

In addition nearby Lund University (established in 1666) has some education located in Malmö:

- Malmö Art Academy (Konsthögskolan i Malmö)

- Malmö Academy of Music (Musikhögskolan i Malmö)

- Malmö Theatre Academy (Teaterhögskolan i Malmö)

- The Faculty of Medicine, which is located in both Malmö and Lund.

The United Nations World Maritime University is also located in Malmö. The World Maritime University (WMU)[49] operates under the auspices of the International Maritime Organization (IMO), a specialized agency of the United Nations. WMU thus enjoys the status, privileges and immunities of a UN institution in Sweden.

Culture

Film and television

A striking depiction of Malmö (in the 1930s) was made by Bo Widerberg in his debut film Kvarteret Korpen (Raven's End) (1963), largely shot in the shabby Korpen working-class district in Malmö. With humour and tenderness, it depicts the tensions between classes and generations. The movie was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1965. In 2017, the film Medan Vi Lever (While We Live) was awarded the prize for best film by an African living abroad at the Africa Movie Academy Awards.[50] It was filmed in Malmö and Gambia, and deals with identity, integration and everyday racism.[51]

The cities of Malmö and Copenhagen are, with the Öresund Bridge, the main locations in the television series The Bridge (Bron/Broen).[52]

Theatre

In 1944, Malmö Stadsteater (Malmö Municipal Theatre) was established with a repertoire comprising stage theatre, opera, musical, ballet, musical recitals and experimental theatre. In 1993 it was split into three units, Dramatiska Teater (Dramatical Theatre), Malmö Musikteater (Music Theatre) and Skånes Dansteater (Skåne Dance Theatre) and the name was abandoned. The ownership of the last two were transferred to Region Skåne in 2006 Dramatiska Teatern regained its old name. In the 1950s Ingmar Bergman was the Director and Chief Stage Director of Malmö Stadsteater and many of his actors, like Max von Sydow and Ingrid Thulin became known through his films. Later stage directors include Staffan Valdemar Holm and Göran Stangertz.[53] Malmö Musikteater were renamed Malmö Operan and plays operas and musicals, classics as newly composed, on one of Scandinavia's large opera scenes with 1,511 seats.[54] Skånes dansteater is active and plays contemporary dance repertory and present works by Swedish and international choreographers in their house in Malmö harbor.[55]

Since the 1970s the city has also been home to independent theatre groups and show/musical companies. It also hosts a rock/dance/dub culture; in the 1960s The Rolling Stones played the Klubb Bongo, and in recent years stars like Morrissey, Nick Cave, B.B. King and Pat Metheny have made repeated visits.

The Cardigans debuted in Malmö and recorded their albums there. On 7 January 2009 CNN Travel broadcast a segment called "MyCity_MyLife" featuring Nina Persson taking the camera to some of the sites in Malmö that she enjoys.

The Rooseum Center for Contemporary Art, founded in 1988 by the Swedish art collector and financier Fredrik Roos and housed in a former power station which had been built in 1900, was one of the foremost centers for contemporary art in Europe during the 1980s and 1990s. By 2006, most of the collection had been sold off and the museum was on a time-out; by 2010 Rooseum had been dismantled and a subsidiary of the National Museum of Modern Art inaugurated in its place.

Music

In 1992 and in 2013 Malmö was the host of the Eurovision Song Contest.[56]

Museums

Moderna Museet Malmö was opened in December 2009 in the old Rooseum building. It is a part of the Moderna Museet, with independent exhibitions of modern and contemporary art. The collection of Moderna Museet holds key pieces of, among others, Marcel Duchamp, Louise Bourgeois, Pablo Picasso, Niki de Saint Phalle, Salvador Dalí, Carolee Schneemann, Henri Matisse and Robert Rauschenberg[57][58]

Malmö Museum (Malmö Museer) is a municipal and regional museum. The museum features exhibitions on technology, shipping, natural history and history. Malmö Museum has an aquarium and an art museum. Malmöhus Castle is also operated as a part of the museum. Exhibitions are primarily shown at Slottsholmen and at the Technology and Maritime Museum (Teknikens och sjöfartens hus).[59] [60] [61] [62]

Malmö Konsthall is one of the largest exhibition halls in Europe for contemporary art, opened in 1975.[63]

Architecture

Malmö's oldest building is St. Peter's Church (Swedish: Sankt Petri). It was built in the early 14th century in Baltic Brick Gothic probably after St Mary's Church in Lübeck. The church is built with a nave, two aisles, a transept and a tower. Its exterior is characterized above all by the flying buttresses spanning its airy arches over the aisles and ambulatory. The tower, which fell down twice during the 15th century, got its current look in 1890.[64] Another major church of significance is the Church of Our Saviour, Malmö, which was founded in 1870.

Another old building is Tunneln, 300 metres (1,000 ft) to the west of Sankt Petri Church, which also dates back to around 1300.

The oldest parts of Malmö were built between 1300–1600 during its first major period of expansion. The central city's layout, as well as some of its oldest buildings, are from this time. Many of the smaller buildings from this time are typical Scanian: two-story urban houses that show a strong Danish influence.

Recession followed in the ensuing centuries. The next expansion period was in the mid 19th century and led to the modern stone and brick city. This expansion lasted into the 20th century and can be seen by a number of Art Nouveau buildings, among those in the Malmö synagogue. Malmö was relatively late to be influenced by modern ideas of functionalist tenement architecture in the 1930s.

Around 1965, the government initiated the so-called Million Programme, intending to offer affordable apartments in the outskirts of major Swedish cities. But this period also saw the reconstruction (and razing) of much of the historical city center.

Since the late 1990s, Malmö has seen a more cosmopolitan architecture. Västra Hamnen (The Western Harbor), like most of the harbor to the north of the city center, was industrial. In 2001 its reconstruction began as an urban residential neighbourhood, with 500 residential units, most were part of the exhibition Bo01.[65] The exhibition had two main objectives: develop self-sufficient housing units in terms of energy and greatly diminish phosphorus emissions. Among the new building's towers were the Turning Torso, a skyscraper with a twisting design, 190 metres (620 ft) tall, the majority of which is residential. It became Malmö's new landmark.[66][67] The most recent addition (2015) is the new development of Malmö Live. This new building features a hotel, a concert hall, congress hall and a sky bar in the center of Malmö. Point Hyllie is a new 110 m commercial tower that is under construction as of 2018.

Other sights

The beach Ribersborg, by locals usually called Ribban,[68] south-west of the harbor area, is a man-made shallow beach, stretching along Malmö's coastline. Despite Malmö's chilly climate, it is sometimes referred to as the "Copacabana of Malmö".[69] It is the site of Ribersborgs open-air bath, opened in the 1890s.

The long boardwalk at The Western Harbor, Scaniaparken and Daniaparken, has become a favorite summer hang-out for the people of Malmö and is a popular place for bathing.[70] The harbor is particularly popular with Malmö's vibrant student community and has been the scene of several impromptu outdoor parties and gatherings.

Annual events

In the third week of August each year a festival, Malmöfestivalen, fills the streets of Malmö with different kinds of cuisines and events.

BUFF International Film Festival, an international children and young people's film festival, is held in Malmö every year in March.

Nordisk Panorama – Nordic Short & Doc Film Festival, a film festival for short and documentary films by filmmakers from the Nordic countries, is held every year in September.

Malmö Arab Film Festival (MAFF), the largest Arabic film festival in Europe, is held in Malmö.

The Nordic Game conference takes place in Malmö every April/May.[71][72] The event consists of conference itself, recruitment expo and game expo and attracts hundreds of gamedev professionals every year.

Malmö also hosts other 3rd party events that cater to all communities that reside in Malmö, including religious and political celebrations.

Media

Sydsvenskan, founded in 1870, is Malmö's largest daily newspaper. It has an average circulation of 130,000. Its main competitor is the regional daily Skånska Dagbladet, which has a circulation of 34,000. The tabloid Kvällsposten still has a minimal editorial staff but is today just a version of a Stockholm tabloid. The Social Democratic Arbetet was edited and printed at Malmö between 1887 and 2000.[73]

In addition to these, a number of free-of-charge papers, generally dealing with entertainment, music and fashion have local editions (for instance City, Rodeo, Metro and Nöjesguiden). Malmö is also home to the Egmont Group's Swedish magazine operations. A number of local and regional radio and TV broadcasters are based in the Greater Malmö area.

Football

Malmö is home to several football teams. Malmö FF, who play in the top-level Allsvenskan league, had their most successful periods in the 1970s and 1980s, when they won the league several times. In 1979, they advanced to the final of the European Cup, defeating AS Monaco, Dynamo Kiev, Wisła Kraków and Austria Wien. In the final, played at the Munich Olympic Stadium against Nottingham Forest, they lost by a single goal scored by Trevor Francis just before half time. To date, they are the only Swedish football club to have reached the final of the competition. Bosse Larsson and Zlatan Ibrahimović began their football careers at Malmö FF. A second football team, IFK Malmö, played in Sweden's top flight for about 20 years. The club's greatest achievement was reaching the quarterfinal in the European Cup. Today IFK Malmö club play in the sixth tier of the Swedish league system.

FC Rosengård (former LdB Malmö) are playing in the top level in Damallsvenskan, women's football league. FC Rosengård girls have won the league 10 times and the national cup title 5 times. In 2014, they reached the semi-final in Champions League, which they ultimately went on to lose to the German side 1. FFC Frankfurt. Brazilian football player Marta, widely regarded the best female football player of all time, played in FC Rosengård between 2014 and 2017.

Malmö Stadion was inaugurated for the opening match of the 1958 FIFA World Cup. The then world champions, West Germany, defeated Argentina 3–1 in front of a crowd of 31,156. A further two games in the cup were decided at the stadium.[74]

Other sports

Malmö has athletes competing in a variety of sport.

Ice hockey

The most notable other sports team is the ice hockey team Malmö Redhawks. They were the creation of millionaire Percy Nilsson and quickly rose to the highest rank in the early to mid-1990s and won two Swedish championships, but for a number of years found themselves residing outside of the top flight. As of the 2015/2016 season they are once again competing in the top flight SHL league.

Rugby

Rugby union team, Malmö RC, founded in 1954, have won 6 national championships. The club has teams for men, women and juniors.[75]

Gaelic football

Gaelic football has also been introduced to Malmö. The men of Malmö G.A.A. have won the Scandinavian Championships twice and the women once.[76]

Additional Team and Individual Sport

Other notable team a sports are baseball, American football and Australian football. Among non-team sports, badminton and athletics are the most popular, together with east Asian martial arts and boxing. Basketball is also fairly a big sport in the city, including the clubs Malbas and SF Srbija among others.

Women are permitted by the city council to swim topless in public swimming pools.[77][78] Everyone must wear bathing attire, but covering of the breasts is not mandatory.[79][80]

Notable events

Notable people

See also

References

- Facts & Figures about Malmö, 2005 at the Wayback Machine (archived 7 October 2006) – in English. From the municipal webpage, PDF format.

- "Malmö stad — Statistik" (in Swedish). Malmö.se. Archived from the original on 21 February 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- Notes

- "Kommunarealer den 1 January 2012" [Municipalities in Sweden and their areas, as of 1 January 2012] (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 30 May 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- https://kommunsiffror.scb.se/?id1=1280&id2=null%5B%5D

- "Folkmängden efter region, civilstånd, ålder och kön. År 1968 – 2015" [Population by region, age and sex. In 1968 – 2015]. Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "Malmö". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "Malmö". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "Malmö definition and meaning". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__MI__MI0810__MI0810A/LandarealTatort/?rxid=546e87f6-5dc3-4535-994e-b301c2515080%5B%5D

- "Folkmängd i riket, län och kommuner 30 september 2016 och befolkningsförändringar 1 juli–30 september 2016. Totalt" [Population in the country, counties and municipalities, 30 September 2016 and population changes 1 July to 30 September 2016. Total]. Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Geography". Tendens Øresund. Archived from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- "Antal personer efter region, utländsk/svensk bakgrund och år" (in Swedish). Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- Lilja, Sven; Nilsson, Lars. "Malmö: Historia". Nationalencyklopedin (in Swedish). NE Nationalencyklopedin. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- "Malmös uppkomst" [Malmö Origins Part 1] (in Swedish). Fotevikens Museum. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ÅRGÅNGEN, TJUGOFEMTE (1957). MALMÖ FORNMINNESFÖ RENING (PDF). Sweden. p. 40.

- "MM 061911:002075 :: Malmö, Centrum, Stortorget, Kvarnstenen, Malmöstenen". malmo.se. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Granskare (1903). "Rikt Folk". Fäderneslandet. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "Så har Malmö vuxit genom åren" (in Swedish). Malmö Municipality. 20 February 2011. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- Utsatta områden – sociala risker, kollektiv förmåga och oönskade händelser (PDF). Police in Sweden – Nationella Operativa Avdelningen – December 2015. p. 29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2016.

- Utsatta områden – Social ordning, kriminell struktur och utmaningar för polisen / Dnr HD 44/14A203.023/2016 (PDF). Police in Sweden – Nationella operativa avdelningen – Underrättelseenheten. June 2017. p. 41. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- "Nederbörd Solsken Och Strålning Året 2014" [Precipitation and Sunshine 2014 (Historical Normals section)] (PDF). Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- "Average Weather in Malmö, Sweden, Year-Round – Weather Spark". weatherspark.com. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- "SMHI Open Data" (in Swedish). SMHI. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Statistics from Weather Stations" (in Swedish). SMHI. 21 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Nederbörd för Lund" (in Swedish). SMHI. April 2015. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- "SMHI Data för väder och vatten" (in Swedish). Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- "Malmö, Sweden – Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- "Cars". Copenhagen Malmö Port. 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- https://www.skane.se/organisation-politik/Vart-uppdrag-inom-kollektivtrafik/Nya-linjer-och-fordon/Nya-taglinjer-och-stationer/Malmoringen/

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Denmark – Sweden cross-border metro project moves forward". Metro Report. 30 May 2018. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- In all official contexts, the town Malmö calls itself "Malmö stad" (or City of Malmö), as does a small number of other Swedish municipalities, and especially the other two metropolitans of Sweden: Stockholm and Gothenburg. However, the term city has administratively been discontinued in Sweden.

- Malmö´s path towards a sustainable future (PDF). The Commission for a Socially Sustainable Malmö. December 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- Befolkningsutveckling Malmö, Malmö Stad. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Befolkningsstatistik 2015. SCB. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Population by region, marital status, age and sex. Year 1968 - 2019". Statistikdatabasen. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Nationalencyklopedin, Article Malmö

- "Befolkningsprognos för Malmö" [Population forecast for Malmö] (in Northern Sami). Malmö Stad. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- "Nu är vi över 300 000" [We are now more than 300,000]. Sydsvenskan. 27 April 2011. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- "Number of persons with foreign or Swedish background (detailed division) by region, age and sex. Year 2002–2018". www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Statistik om Malmö". ssd.scb.se Search data for Malmö through the search bar.

- Necmi Incegül. "Statistik om Malmö – Malmö stad". Malmo.se. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "Foreign citizens by region, age in ten year groups and sex. Year 1973 - 2019". Statistikdatabasen. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Definitions of Metropolitan Areas in Sweden". Archived from the original on 30 December 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2008.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Population by region, marital status, age and sex. Year 1968 - 2019". Statistikdatabasen. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Alexandru Panican, Håkan Johansson, Max Koch, Anna Angelin (2013). The local arena for combating poverty Malmö, Sweden (PDF).CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Region Skåne".

- "Malmö City" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- Malmö Snapshot Facts and figures on trade and industry in Malmö, Malmö stad.

- Malmö Snapshot Facts and figures on trade and industry in Malmö, Malmö stad

- "World Maritime University". Wmu.se. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "Africa Movie Academy Awards 2017 Nominees & Winners". Africa Movie Academy Awards. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- Larsson, Camilla (7 October 2016). "Malmöfilmen berör – men spretar". Sydsvenskan. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- The Bridge at IMDb

- "Malmö Stadsteater" (in Swedish). Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- "Malmö Opera och Musikteater". Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- "About us | Skånes Dansteater". Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- "Malmö to host Eurovision Song Contest 2013!". eurovision.tv. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- "Malmö stad — Moderna Museet Malmö" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 17 April 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- "Samlingen — Moderna Museet" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- "Malmö Museer". malmo.se. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Malmöhus Castle". malmo.se. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Slottsholmen". slottsholmen.com. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Teknikens och Sjöfartens hus". malmo.se. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "About Malmö Konsthall". Malmö Konsthall. Archived from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- "Svenska kyrkan — Malmö S:t Petri församling — S:t Petri kyrka — Malmös katedral" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- City of Malmö website. "Western Harbour/Bo01". Archived from the original on 6 January 2010.

- Arkitekterna som formade Malmö, Tyke Tykesson (1996), ISBN 91-7203-113-1

- Web site Malmö Arkitekturhistoria Arkitekturhistoria Archived 22 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine, a brief compilation made by Malmö Public Library website. Accessed 19/05 -06. Has a substantial reference section. (in Swedish)

- City of Malmö website. "Strandliv: Ribersborgsstranden" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 18 April 2013.

- City of Malmö website. "Kulturarv: Ribersborgsstranden" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 8 August 2011.

- City of Malmö website. "Strandliv: Scaniabadet" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 7 July 2013.

- "Nordic Game". Nordic Game. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Nordic Game Conference | Media Evolution". Mediaevolution.se. 7 April 2011. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "History". Malmö FF. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- "Teams – Malmo Rugby". Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- "About Us – Malmö GAA". Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- "Malmö win for topless Swedish bathers — The Local". Thelocal.se. Archived from the original on 27 June 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- "Women fight for right to bare breasts — The Local". Thelocal.se. 1 July 2009. Archived from the original on 21 September 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- The Earthtimes. "Swedish feminists win partial approval for topless swimming: Europe World". Earthtimes.org. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- "Swedish city legalizes topless bathing....at public swimming pools". Inquisitr.com. 27 June 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

Further reading

- "Malmö", Norway, Sweden, and Denmark (8th ed.), Leipsic: Karl Baedeker, 1903, OL 16522424M

- Article Malmö from Nordisk familjebok, 1912 (in Swedish)

External links

| Look up Malmö in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malmö. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Malmö. |

- Official municipal site in Swedish and English

- Malmotown.com, Malmö official visitor site

- Malmöfestivalen

- Maps of Malmö (in Swedish)

- Malmo