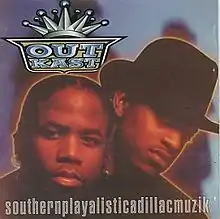

Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik

Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik is the 1994 debut album of American hip hop duo Outkast. After befriending each other in 1992, rappers André 3000 and Big Boi pursued recording music as a duo and worked with production team Organized Noize, which led to their signing to LaFace Records. The album was produced by the team and recorded at the Dungeon, D.A.R.P. Studios, Purple Dragon, Bosstown, and Doppler Studios in Atlanta.

| Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | April 26, 1994 | |||

| Recorded | 1993–94 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | Southern hip hop | |||

| Length | 64:33 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | Organized Noize | |||

| Outkast chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Southernplaya listicadillacmuzik | ||||

| ||||

A Southern hip hop record, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik features live instrumentation in its hip hop production and musical elements from funk and soul genres. Wanting to make a statement about urban life as an African American in the South, Outkast wrote and recorded the album as teenagers and addressed coming of age themes with the album's songs. They also incorporated repetitive hooks and Southern slang in their lyrics.

Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik was released by LaFace on April 26, 1994, and peaked at number 20 on the Billboard 200, eventually being certified platinum in the United States. The record received positive reviews from critics and helped distinguish Southern hip hop as a credible hip hop scene, amid East Coast and West Coast hip hop's market dominance at the time. The album has since been viewed by music journalists as an important release in both hip hop and Atlanta's music scene.

Background

André 3000 and Big Boi met in 1992 at the Lenox Square shopping mall when they were both 16 years old.[1] The two lived in the East Point section of Atlanta and attended Tri-Cities High School.[1] During school, they participated in rap battles in the cafeteria.[1] André 3000 dropped out of high school at age 17 and worked a series of jobs before he and Big Boi formed a group called 2 Shades Deep;[2] he returned to obtain his GED at a night school following the release of Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik.[3] They briefly dabbled in street-hustling to save up for recording money.[4]

The duo also spent time at their friend Rico Wade's basement recording studio, known as the Dungeon,[5] with Wade's production team Organized Noize and future members of hip hop group Goodie Mob.[1][6] Outkast recorded demos at the studio,[6] and Organized Noize member Ray Murray helped Big Boi, whose strength lay in songwriting, develop his rapping skills.[3] After several local productions, the team was hired by LaFace Records to produce remixes to songs from TLC's 1992 album Ooooooohhh... On the TLC Tip.[6] The team had André 3000 and Big Boi rap over them, which led to a record deal from LaFace for both Organized Noize and OutKast.[6] The commercial success of Arrested Development's 1992 alternative hip hop single "Tennessee" also encouraged LaFace to sign Outkast,[7] the label's first hip hop act.[8]

Recording and production

After receiving a $15,000 advance from LaFace in 1993, Outkast started recording the album at the Dungeon.[10] The studio featured mostly secondhand recording equipment.[5] Recording sessions also took place at Bosstown, Dallas Austin's D.A.R.P. Studios,[11] Doppler Studios, and Purple Dragon in Atlanta.[12] Located in midtown Atlanta, Bosstown developed a sentimental value for Outkast, who later bought the studio in 1999 and renamed it "Stankonia" after their fourth studio album.[11] Throughout the album's recording, the duo refined their artistry and drew on ideas from funk, contemporary R&B, and soul music.[13] André 3000 also smoked marijuana during the sessions.[14] They recorded over 30 songs for the album.[13]

Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik was produced entirely by Organized Noize, which was made up of Rico Wade, Ray Murray, and Sleepy Brown.[12] Production team Organized Noize utilized live instrumentation on the album, emphasizing musical instruments, including bass, keyboards, guitar,[15] and organ,[16] over conventional hip hop techniques such as DJing and sampling.[17] They viewed that the feel of live instruments made the music sound more authentic and immediate.[15] With their production, the team sought an organic, celebratory, "down-home" vibe, as Brown later recalled, "We wanted Atlanta brothers to be proud of where they were from".[18] Brown also sung vocals for several tracks.[12]

Along with Organized Noize, other members of the Dungeon Family worked on the album,[18] including Goodie Mob, Mr. DJ, Debra Killings, and Society of Soul.[12] The album was mixed at Sound on Sound in New York City, Bosstown, D.A.R.P. Studios, Tree Sound, and Studio LaCoCo in Atlanta.[12]

Music and lyrics

A Southern hip hop album, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik incorporates analog elements such as Southern-styled guitar licks, languid soul melodies, and mellow 1970s funk grooves.[20][21] It also features digital hip hop production elements such as programmed snare beats, booty bass elements,[20] including Roland TR-808 clave rhythms,[9] and old school hip hop elements, including E-mu SP-1200-styled drums and turntable scratches.[22] Music writers characterize the album's music and beats as "clanky" and "mechanical".[20][23] Roni Sarig of Rolling Stone comments that the music shows "clear debts to East Coast bohos like the Native Tongues and a West Coast level of attention to live instruments and smooth, irresistible melodies".[17] In Oliver Wang's Classic Material, music writer Tony Green delineates the album's release "at the tail end of a second hip-hop 'golden age,' a two-year period (1993–94) that spawned Wu-Tang's Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), Snoop Dogg's Doggystyle, De La Soul's Buhloone Mindstate, Nas's Illmatic, and A Tribe Called Quest's Midnight Marauders", and comments that "like many albums released during that period, Southernplayalistic alluded to its roots ... while clearing the way for a new direction that used the peach cobbler soul funk of the Organized Noize production crew as a starting point."[22]

With the album, Outkast wanted to make a statement about urban life as an African American in the South, particularly Atlanta.[15] Written when they were teenagers, much of the album addresses coming of age topics,[17][23] and has themes of self-empowerment and reflections on life in the New South.[24] Encyclopedia of Popular Music editor Colin Larkin writes that the album "compris[es] tales of the streets of their local East Point and Decatur neighbourhoods".[25] The album's segue tracks illustrate Southern life.[26] The lyrics incorporate tongue-twisters, triplet rhyme schemes,[22] repetitive vocal hooks, Southern slang, such as the recurring phrase "ain't no thang but a chicken wing" repeated throughout "Ain't No Thang".[17][20] The duo also intersperse their lyrics with references to classic cars, marijuana use, pimps,[18] and players,[23] which Big Boi defines as "somebody who can take care of they business in the game, the game of life".[27] His flow is frenetic and has a rapid delivery, while André 3000 raps in a more relaxed cadence, with staccato rhymes,[28] and occasionally sings on the album.[26] Writer Martin C. Strong views that both rappers' "lyrical panache" on the album has an "ebb and flow" similar to Kool Keith and Del the Funky Homosapien.[29]

The song "Call of da Wild" discusses the temptation to drop out of school, while "Git Up, Git Out" encourages teenagers to follow their passions, be productive,[21] and stop using drugs.[23][30] The latter is an intertextual track that mixes themes of consciousness and political awareness with images of violence, sex, drugs, and gangsta culture.[8] It features guest rapper Cee Lo Green exploring perspectives of both man child and maternal figure.[23] "Funky Ride" has no rappers and is instead sung by R&B group Society of Soul,[12] a side project of Organized Noize.[31] It has an extended guitar solo and musical similarities to Funkadelic and Bootsy Collins.[16][32] "Crumblin' Erb" explores themes of hedonism and addresses black-on-black violence and the negative effect it has on African-American culture: "There's only so much time left in this crazy world / I'm just crumblin' erb / Niggas killin' niggas, they don't understand (it's the master plan), I'm just crumblin' erb"[23]

Marketing and sales

The album's lead single, "Player's Ball", was released on November 19, 1993,[33] Originally intended as a Christmas release, it featured the sound of sleigh bells in its original mix, but it was removed once the single began receiving more airplay.[34] The single received its highest exposure in February 1994 with heavy airplay and promotion, including a music video directed by Sean "Puffy" Combs.[34] Combs had received a copy of the single from LaFace founder L.A. Reid and invited Outkast to New York to perform as an opening act for The Notorious B.I.G.[34] By March, the single had sold 500,000 copies and risen to number one on the Billboard Hot Rap Singles, topping the chart for six weeks.[27] Its popularity among young black college students during Freaknik increased its sales and helped it break into the Top 40, a rare achievement for a hip hop song at the time.[35] "Player's Ball" spent 20 weeks and peaked at number 37 on the Billboard Hot 100.[36] On May 12, 1994, it was certified gold by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in the United States.[33] The single helped create buzz for the album.[37]

LaFace released Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik on April 26, 1994.[33] On May 14, it peaked at number 20 on the US Billboard 200.[38] The album ultimately spent 26 weeks on the chart.[38] It also reached number three on the Billboard Top R&B Albums, remaining on the chart for 50 weeks.[38] By June, the album had sold 500,000 copies.[39] The album's sales increased after Outkast's appearance at the 1995 Source Awards in January.[40] On April 5, 1995, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik was certified platinum by the RIAA, for shipments of one million copies in the US.[33] By August, it had sold 715,000 copies, according to Nielsen SoundScan.[41] The album was reissued by LaFace in September 1998.[29]

Neither of the album's next two singles performed as well.[42] The title track was released in July 1994,[29] reaching number 74 on the Billboard Hot 100 in August.[38] Its music video was directed by F. Gary Gray.[43] "Git Up, Git Out" was released in October.[29] It only charted on the Billboard Hot R&B Singles, peaking at number 59.[44]

Critical reception

Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik was met with generally positive reviews. James Bernard of Entertainment Weekly preferred the album's Southern hip hop over "Arrested Development's suspiciously peppy, idealized version of down-home" and stated, "it's about time someone told today's weed-obsessed youth to 'get up, get out and get something/Don't spend all your time trying to get high.'"[30] Dennis Hunt of the Los Angeles Times cited "Git Up, Git Out" as the album's highlight and commended the duo's "sauntering, hard-core tales of the 'hood", writing that they "bristle with clever humor and sharp insights rather than rage."[21] Rob Marriott of The Source complimented the duo's "organic" P-Funk influence and praised their lyrics' honesty, commenting that "while their rhyme style may swing a little too close to Hiero for my comfort, what really makes this album so listenable is that ... truthfulness reigns."[23] However, Robert Christgau dismissed the album as a "dud" in his consumer guide for The Village Voice.[48]

Despite the album's success, some reacted negatively to the musical style, particularly hip hop tastemakers.[35] At the 1995 Source Awards, Outkast won in the "Best Newcomer" category,[29] but were booed upon taking the stage and delivering their acceptance speech; Big Boi managed to deliver his shout outs, while André 3000 was nervous and only said, "The South got somethin' to say."[8] The latter recalled how the album was received by some listeners, "People thought that the South basically only had bass music. At first people were looking at us like 'Um, I don't know.'"[35] Hip hop magnate Russell Simmons reacted negatively to the album at the time, but later expressed regret and said of the album in retrospect, "At the time, I didn't understand their music—it sounds so different from what I was used to that I foolishly ... claim[ed] that they 'weren't hip-hop.' The same way people didn't understand 'Sucker MCs' a decade earlier, I didn't understand that instead of operating outside of hip-hop, OutKast was actually expanding hip-hop. They were offering one of the most honest expressions, and expression so honest that it went completely over my head at first."[49]

In retrospect, Christgau remarked said, "If Dre and Big Boi were addressing real 'real life situations' on Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik or ATLiens, they were drawling too unreconstructedly for any Yankee to tell."[50] Steve Juon of RapReviews was more receptive, calling it "a stellar debut album", albeit with some musical flaws, including the "monotonous bassline and chorus" of "D.E.E.P.", the "out of place" "Funky Ride", and the album's segue tracks.[51] Music journalist Peter Shapiro found its production "rich, deep and detailed, but never as seductive or crowd-pleasing as Dr. Dre's" and commended the album as "a melancholy depiction of the game that never shied away from its consequences".[9] Although he found "occasional dull and mediocre spots", AllMusic editor Stanton Swihart called the album "an extremely strong showing" and praised the duo's "inventive sense of rhyme flow" and "mixture of lyrical acuity, goofball humor, Southern drawl, funky timing, and legitimate offbeat personalities."[20]

Legacy and influence

After the album was certified platinum, LaFace Records gave Outkast more creative control and advanced money for their 1996 follow-up album ATLiens.[52] After acquiring their own recording studio, the duo immediately started working on new material and assimilated themselves with music recording and studio equipment, as they sought to become more ambitious artists and less dependent on other producers.[53] The two also became more accustomed to playing live, particularly Big Boi, and André 3000 significantly changed his lifestyle, as he adopted a more eccentric fashion sense, became a vegetarian, and stopped smoking marijuana.[54] The album's success also opened up more opportunities for Organized Noize, who subsequently worked on TLC's CrazySexyCool (1994).[31] The Organized Noize-produced hit "Waterfalls" became a massive success and earned the production team enough clout with LaFace to endorse Goodie Mob to the label.[55] Organized Noize produced Goodie Mob's acclaimed 1995 debut Soul Food and continued their crossover into R&B production, including work on Curtis Mayfield's 1997 album New World Order.[31]

Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik was a seminal album for Southern hip hop.[56] During the early 1990s, the scene was largely discredited by the rest of the hip hop community as misogynistic and inferior to other scenes, particularly East Coast and West Coast hip hop.[23] Those scenes dominated the hip hop market, and acts from other regional scenes were often produced by either East Coast or West Coast producers.[8] The album offered an artistically credible alternative, both musically and lyrically, to those regional scenes and was produced by an Atlanta-based production team.[8][26] Music journalist T. Hasan Johnson notes "Outkast's first submission to the music industry" as significant for how they "broke from the binary production options split by California and New York artists", viewing that their decision to boast their region and a native production team "signaled a break from the conventional split between East and West hip hop aesthetics and openly demonstrated that the South could produce street-certified, quality music."[8] Nicole Hodges Persley cites its release as a critical moment in hip hop and writes that it "marked a break in bicoastal hip hop sound".[57]

The album presaged hip hop's "Dirty South" aesthetic, which later achieved mainstream recognition.[32] Its smooth musical style, drawing on soul and funk musical traditions,[8] and the duo's clever lyrics helped define Southern hip hop's sound,[25][58] which influenced acts like Goodie Mob, Joi, and Bubba Sparxxx.[57] In The New Rolling Stone Album Guide, Rolling Stone journalist Roni Sarig writes that the album "marked a coming out for a region that would dominate hip-hop by the decade's end", commenting that, with it, Outkast "helped define a new stream of hip-hop that would rejuvenate the music in the late '90s and early 2000s."[17] AllMusic's Stanton Swihart comments that "no one sounded like OutKast in 1994" and that the album showcased Organized Noize as it "began forging one of the most distinctive production sounds in popular music in the '90s".[20]

Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik was also a significant release during the burgeoning Hotlanta music scene.[32][34] The scene started as a black music revival in Atlanta during the late 1980s,[59] and developed with the success of LaFace Records and the national attention received by Atlanta-based recording artists and producers such as Toni Braxton, Kris Kross, Jermaine Dupri, and Babyface.[32][34] The album offered realistic depictions of the city and veered from the Afrocentric themes of Arrested Development and Dupri's mainstream stylings.[32] It was named the third best album of 1994 in ego trip's list of "Hip Hop's 25 Greatest Albums by Year 1980–98".[60] Vibe included it as one of the "150 Essential Albums of the Vibe Era (1992–2007)".[61] The magazine also included the album on their 2004 list of "51 Essential Albums" that represent "a generation, a sound, and in many cases, a movement", writing that "[OutKast] determined the South had something to say, and after emerging form the Dungeon production lab, they said it all, sometimes sang it all—pointedly, funkdafied, and putting on absolutely no East Coast pretense. Classic."[62]

Track listing

- All tracks produced by Organized Noize

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Peaches (Intro)" | 0:51 | |

| 2. | "Myintrotoletuknow" | 2:40 | |

| 3. | "Ain't No Thang" |

| 5:39 |

| 4. | "Welcome to Atlanta (Interlude)" | 0:58 | |

| 5. | "Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik" |

| 5:18 |

| 6. | "Call of da Wild" (featuring Goodie Mob) |

| 6:06 |

| 7. | "Player's Ball" |

| 4:21 |

| 8. | "Claimin' True" |

| 4:43 |

| 9. | "Club Donkey Ass (Interlude)" |

| 0:25 |

| 10. | "Funky Ride" |

| 6:31 |

| 11. | "Flim Flam (Interlude)" | 1:15 | |

| 12. | "Git Up, Git Out" (featuring Goodie Mob) |

| 7:27 |

| 13. | "True Dat (Interlude)" | 1:16 | |

| 14. | "Crumblin' Erb" |

| 5:10 |

| 15. | "Hootie Hoo" |

| 3:59 |

| 16. | "D.E.E.P." |

| 5:31 |

| 17. | "Player's Ball (Reprise)" |

| 2:20 |

- Notes

- "Funky Ride" is sung by Society of Soul.[51]

- "Flim Flam (Interlude)" contains a sample of "Ghetto Head Hunta" by P.A.[12]

Personnel

Credits are adapted from the album's liner notes.[12]

|

|

Charts

| Chart (1994) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard 200[38] | 20 |

| US Billboard Top R&B Albums[38] | 3 |

See also

References

- Guzman, Isaac (October 22, 2000). "Melody Makers of Hip-Hop". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles: Tribune Company. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Lester, Paul (May 18, 2001). "PARTNERS IN RHYME: One of them is a blonde-wigged, teetotal vegetarian who reads Pushkin. The other breeds pitbulls in his spare time. Together they have been called the 'greatest living hip-hop act'. Paul Lester hits the road with OutKast". The Guardian. London: Guardian Media Group.

- Nickson (2004), p. 23.

- Norris, Chris (December 2000). "Funk Soul Brothers". Spin. Vibe/Spin Ventures. 16 (12): 146. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Nickson (2004), p. 21.

- Nickson (2004), pp. 24–25.

- Nickson (2004), p. 26.

- Johnson et al. Hess (2007), pp. 460–461.

- Shapiro et al. Buckley (2003), p. 762.

- Nickson (2004), pp. 29–30.

- Bry, David (December 2000). "Scentimental Journey". Vibe. Vibe/Spin Ventures. 8 (10): 144. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik (CD liner). OutKast. LaFace Records. 1994. 73008-26010-2.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Nickson (2004), p. 32.

- Westhoff (2011), p. 110.

- Nickson (2004), p. 31.

- Nickson (2004), p. 40.

- Sarig et al. Brackett & Hoard (2004), p. 610.

- Westhoff (2011), p. 103.

- Dersch (2010), p. 4.

- Swihart, Stanton. "Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik – OutKast". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Hunt, Dennis (June 26, 1994). "OutKast, 'Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik,' LaFace". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles: Tribune Company. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Green et al. Wang (2003), p. 132.

- Marriott, Rob (July 1994). "Outkast: Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik". The Source. New York (58): 83. Archived from the original on July 6, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Baker, Soren (October 25, 1998). "OutKast Aquemini (LaFace-Arista) As one of the ..." Chicago Tribune. Chicago: Tribune Company. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Larkin (2006), p. 357.

- Nickson (2004), p. 39.

- Nickson (2004), p. 34.

- Westhoff (2011), p. 102.

- Strong (2004), p. 1134.

- Bernard, James (May 27, 1994). "Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik". Entertainment Weekly. New York: Time Inc. (224): 88. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Nickson (2004), p. 41.

- Green et al. Wang (2003), p. 133.

- "Searchable Database". Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). If necessary, click Advanced, then click Format, then select Album, then click SEARCH. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Nickson (2004), pp. 32–33.

- Nickson (2004), p. 35.

- "Player's Ball [Original Version] – OutKast". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Bush, John. "Outkast – Biography". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- "Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik – OutKast". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Nickson (2004), p. 36.

- Nickson (2004), p. 43.

- Reynolds, J. R. (August 5, 1995). "Production Group Makes Positive Noize; Get Those Grammy Nominations Mailed". Billboard. BPI Communications. 107 (31): 19. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Nickson (2004), p. 37.

- Itzkoff, David (February 2005). "Exposure". Spin. Vibe/Spin Ventures. 21 (2): 34. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- "Git Up, Git Out – OutKast". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Murray, Sonia (May 7, 1994). "Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik: OutKast". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Christgau, Robert (2000). "OutKast: Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik". Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 237. ISBN 0312245602. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- "Outkast – Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik User Opinions". Sputnikmusic. Scroll down to Louis Arp. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Christgau, Robert (July 11, 1995). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Simmons (2008), p. 54.

- Christgau, Robert. "Albums: OutKast: Aquemini". Robert Christgau. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Juon, Steve (April 21, 2002). "OutKast :: Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik :: LaFace/Arista Records". RapReviews. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Black Diaspora. New York: Black Diaspora Communications. 18: 25. 1997. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Nickson (2004), p. 42.

- Nickson (2004), p. 46.

- Westhoff (2011), p. 104.

- Joyner (2008), p. 292.

- Persley et al. Hess (2007), p. xxviii.

- Mack (2009), p. 21.

- Nickson (2004), pp. 19–20.

- Jenkins (1999), p. 335.

- "Revolutions". Vibe. Vibe Media Group. 15 (3): 212. March 2007. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- "51 Essential Albums". Vibe. Vibe/Spin Ventures. 12 (9): 210. September 2004. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

Bibliography

- Buckley, Peter, ed. (November 1, 2003). The Rough Guide to Rock (3rd ed.). Rough Guides. ISBN 1-84353-105-4.

- Dersch, Timo (December 6, 2010). "Gangsta Rap" – The Move from Inner City Slums to Profitable Entertainment. GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-640-77004-5.

- Hess, Mickey, ed. (2007). Icons of Hip Hop: An Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-33903-5.

- Jenkins, Sacha; Wilson, Elliott (December 3, 1999). Jenkins, Sacha (ed.). Ego Trip's Book of Rap Lists. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-24298-0.

- Joyner, David Lee (June 27, 2008). American Popular Music (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 978-0-07-352657-7.

- Larkin, Colin, ed. (2006). "Outkast". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Indexes, Volume 10 (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-531373-9.

- Mack, Jim (September 1, 2009). Hip-Hop. Heinemann-Raintree Library. ISBN 978-1-4109-3393-5.

- Nickson, Chris (September 1, 2004). Hey Ya!: The Unauthorized Biography Of Outkast. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-33735-3.

- Sarig, Roni (November 1, 2004). "OutKast". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Simmons, Russell; Morrow, Chris (April 22, 2008). Do You!: 12 Laws to Access the Power in You to Achieve Happiness and Success. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-1-59240-368-4.

- Strong, Martin Charles (October 21, 2004). The Great Rock Discography (7th ed.). Canongate U.S. ISBN 1-84195-615-5.

- Wang, Oliver, ed. (May 1, 2003). Classic Material: The Hip-Hop Album Guide. ECW Press. ISBN 1-55022-561-8.

- Westhoff, Ben (May 1, 2011). Dirty South: OutKast, Lil Wayne, Soulja Boy, and the Southern Rappers Who Reinvented Hip-Hop. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-56976-606-4.

External links

- Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik at Discogs (list of releases)