St Cuthbert Gospel

The St Cuthbert Gospel, also known as the Stonyhurst Gospel or the St Cuthbert Gospel of St John, is an early 8th-century pocket gospel book, written in Latin. Its finely decorated leather binding is the earliest known Western bookbinding to survive, and both the 94 vellum folios and the binding are in outstanding condition for a book of this age. With a page size of only 138 by 92 millimetres (5.4 in × 3.6 in), the St Cuthbert Gospel is one of the smallest surviving Anglo-Saxon manuscripts. The essentially undecorated text is the Gospel of John in Latin, written in a script that has been regarded as a model of elegant simplicity.

The book takes its name from Saint Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, North East England, in whose tomb it was placed, probably a few years after his death in 687. Although it was long regarded as Cuthbert's personal copy of the Gospel, to which there are early references, and so a relic of the saint, the book is now thought to date from shortly after Cuthbert's death. It was probably a gift from Monkwearmouth–Jarrow Abbey, where it was written, intended to be placed in St Cuthbert's coffin in the few decades after this was placed behind the altar at Lindisfarne in 698. It presumably remained in the coffin through its long travels after 875, forced by Viking invasions, ending at Durham Cathedral. The book was found inside the coffin and removed in 1104 when the burial was once again moved within the cathedral. It was kept there with other relics, and important visitors were able to wear the book in a leather bag around their necks. It is thought that after the Dissolution of the Monasteries in England by Henry VIII between 1536 and 1541, the book passed to collectors. It was eventually given to Stonyhurst College, the Jesuit school in Lancashire.

From 1979 it was on long-term loan from the British province of the Jesuit order to the British Library, catalogued as Loan 74. On 14 July 2011 the British Library launched a fundraising campaign to buy the book for £9 million, and on 17 April 2012 announced that the purchase had been completed and the book was now British Library Add MS 89000.[1]

The library plans to display the Gospel for equal amounts of time in London and Durham. It describes the manuscript as "the earliest surviving intact European book and one of the world's most significant books".[2] The Cuthbert Gospel returned to Durham to feature in exhibitions in 2013 and 2014, and was in the British Library's Anglo-Saxon exhibition in 2018/19; it also spends periods "resting" off display. A new book on the gospel was published in 2015, incorporating the results of research since the purchase; among other things this pushed the likely date from the late 7th century to between around 700 and 730.

Description

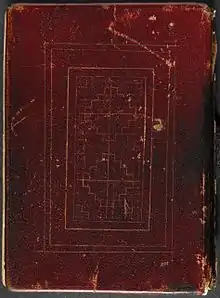

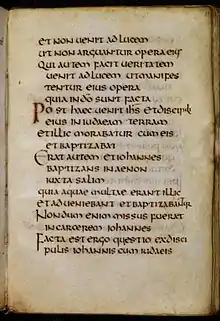

The St Cuthbert Gospel is a pocket-sized book, 138 by 92 millimetres (5.4 × 3.6 in), of the Gospel of St John written in uncial script on 94 vellum folios. It is bound in wooden cover boards, covered with tooled red leather.[3]

Context

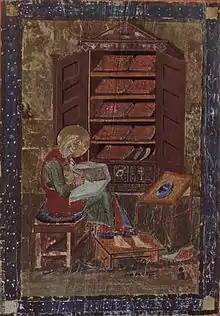

The St Cuthbert Gospel is significant both intrinsically as the earliest surviving European book complete with its original binding and by association with the 7th-century Anglo-Saxon saint Cuthbert of Lindisfarne.[2] A miniature in the Codex Amiatinus, of the Prophet Ezra writing in his library, shows several books similarly bound in red decorated with geometric designs. This miniature was probably based on an original in the Codex Grandior, a lost imported Italian Bible at Jarrow, which showed Cassiodorus and the nine volumes he wrote of commentary on the Bible. Whether the bindings depicted, which were presumably of leather, included raised elements cannot be detected, but the books are stored singly flat in a cupboard, which would reduce the wear on any raised patterns.[4]

Early medieval treasure bindings with a structure in precious metal, and often containing gems, carved ivory panels or metal reliefs, are perhaps better known today than leather bindings, but these were for books used in church services or as "book-icons" rather than for use in libraries.[5] Of treasure bindings from this period, only the lower cover of the Lindau Gospels (750–800, Morgan Library) now survives complete, though there are several references to them, most famously to that of the Book of Kells, which was lost after a theft in 1007. Various metal fragments of what were probably book-mounts have survived, usually adapted as jewellery by Vikings. In the context of the cult of Cuthbert, the lavishly illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels were made at Lindisfarne, probably shortly after the St Cuthbert Gospel, with covers involving metalwork, perhaps entirely made in it, which are also now lost.[6] Plainer, very early bindings in leather are almost as rare as treasure bindings, as the bindings of books in libraries usually wore out and needed to be renewed, and earlier collectors did not consider most historical bindings worth retaining.[7]

Text

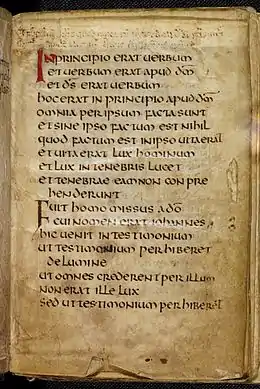

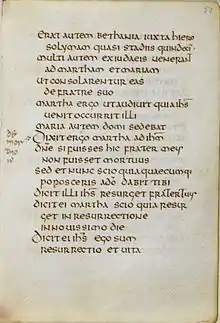

The text is a very good and careful copy of the single Gospel of John from what has been called the "Italo-Northumbrian" family of texts, other well-known examples of which are several manuscripts from Wearmouth–Jarrow, including the Codex Amiatinus, and in the British Library the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Gospel Book MS Royal 1. B. VII. This family is presumed to have derived from a hypothetical "Neapolitan Gospelbook" brought to England by Adrian of Canterbury, a companion of Theodore of Tarsus who Bede says had been abbot of Nisida, an equally hypothetical monastery near Naples. In the rubrics of the Lindisfarne Gospels are several that are "specifically Neapolitan", including festivals which were celebrated only in Naples such as The Nativity of St. Januarius and the Dedication of the Basilica of Stephen. The Neapolitan manuscript was probably at Wearmouth–Jarrow.[8]

Apart from enlarged and sometimes slightly elaborated initials opening the Ammonian Sections (the contemporary equivalent of the modern division into verses), and others in red at the start of chapters, the text has no illumination or decoration,[9] but Sir David Wilson, historian of Anglo-Saxon art and Director of the British Museum, used it as his example in writing "some manuscripts are so beautifully written that illumination would seem only to spoil them".[10] Julian Brown wrote that "the capitular uncial of the Stonyhurst Gospel owes its beauty to simple design and perfect execution. The decorative elements in the script never interfere with the basic structure of the letter-forms; they arise naturally from the slanted angle at which the pen was held".[11]

The pages with the text have been ruled with a blind stylus or similar tool, leaving just an impression in the vellum. It can be shown that this was done for each gathering with just two sets of lines, ruled on the outermost and innermost pages, requiring a very firm impression to carry the marks through to the sheets behind. Impressed lines mark the vertical edges of the text area, and there is an outer pair of lines. Each line of text is ruled, only as far as the inner vertical lines, and there are prick marks where the horizontal lines meet the verticals. The book begins with 19 lines on a page, but at folio 42 changes to 20 lines per page, requiring the re-ruling of some pages. This change was evidently a departure from the original plan, and may have been caused by a shortage of the very fine vellum, as two different sorts are used, though the change does not coincide exactly with the change in the number of lines.[12]

Four passages are marked in the margin, which correspond to those used as readings in Masses for the Dead in the Roman lectionary of the mid-7th century. This seems to have been done hastily, as most left offset marks on the opposite pages from the book being closed before the ink was dry.[13] This seems to indicate that the book was used at least once as the gospel book for a Mass for the Dead, perhaps on the occasion of Cuthbert's elevation in 698. In the example illustrated at left, the start of the reading at line 10 is marked with a cross, and de mortuorum ("for the dead") written beside. The reading ends on the next page, which is also marked.[14]

Binding

_is_the_oldest_intact_European_book._-_Upper_cover_(Add_Ms_89000)_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The original tooled red goatskin binding is the earliest surviving intact Western binding, and the virtually unique survivor of decorated Insular leatherwork.[15] The decoration of the front cover includes colour, and the main motif is raised, which is unique among the few surviving Early Medieval bindings.[16] The panels of geometrical decoration with two-stranded interlace closely relate to Insular illuminated manuscripts, and can be compared to the carpet pages found in these.[17] Elements of the design also relate to Anglo-Saxon metalwork in the case of the general origin of interlace in manuscripts,[18] and Coptic and other East Mediterranean designs.[19]

The decoration of the covers includes three pigments filling lines engraved with a sharp pointed instrument, which now appear as two shades of yellow, one bright and the other pale, and a dark colour that now appears as blue-grey, but was recorded as blue in the earliest descriptions. The front cover includes all three colours, but the pale yellow is not used on the back cover. The pigments have been analysed for the first time, as one benefit of the purchase of the manuscript by the British Library, and identified by Raman spectroscopy as orpiment (yellow) and indigo (grey-blue).[20] The balance of the designs on both covers is now affected by what appears to be the greater fading of the dark blue-grey pigment.[21] The bookbinder Roger Powell speculated that the "pale lemon-yellow ... may once have been green", giving an original colour scheme of blue, green and yellow on the red background,[22] although the recent testing suggests this was not the case.

Given the lack of surviving objects, we cannot know how common the techniques employed were, but the quality of the execution suggests that the binder was experienced in them.[23] At the same time, an analysis by Robert Stevick suggests that the designs for both covers were intended to follow a sophisticated geometric scheme of compass and straightedge constructions using the "two true measures of geometry", the ratio between Pythagoras' constant and one, and the golden section. However slips in the complicated process of production, some detailed below, mean that the finished covers do not quite exhibit the intended proportions, and are both slightly out of true in some respects.[24]

Although it seems clear from the style of the script that the text was written at Monkwearmouth–Jarrow, it is possible that the binding was then added at Lindisfarne; the form of the plant scrolls can be compared to those on the portable altar also found in Cuthbert's coffin, presumed to have been made there, though also to other works of the period, such as the shaft of an Anglo-Saxon cross from Penrith and the Vespasian Psalter. Small holes in the folds of each gathering seem to represent a "temporary sewing" together of the pages, one explanation of which is a journey made by the unbound pages.[25]

Front cover

The decoration of the front cover is divided into fields bordered by raised lines. The central field contains a plant motif representing a stylised chalice in the centre with a bud and scrolling vine stems leading from it, fruit and several small leaves.[26] Above and below the central motif are fields containing interlace ornament in finely incised lines. The three motifs are enclosed within a border containing further interlacing.

Continuous vine scrolls in a great variety of designs of the same general type as the central motif, with few leaves and round fruits, were very common in slightly later religious Anglo-Saxon art, and are often combined with interlace in the same work, especially on Anglo-Saxon crosses, for example the Bewcastle Cross and the Easby Cross now in the Victoria and Albert Museum.[27] One face of the fragmentary silver cover of the portable altar also recovered from Cuthbert's coffin has a similar combination of elements, with both areas of interlace and, in the four corners, a simple plant motif with a central bud or leaf and a spiral shoot on either side.[28] The combination of different types of ornament within a panelled framework is highly typical of Northumbrian art, above all the Lindisfarne Gospels.[29] Interlace may well have still been believed to have some quasi-magical protective power, which seems to have been its function in pre-Christian Germanic art.[30] The vine motif here differs from the common continuous scroll type in that the stems cross over each other twice on each side, but crossing stems are also seen on the upper north face of the Bewcastle Cross and a cross in the church at Hexham.[31] Meyer Schapiro compares the motif with one in an initial in the later Book of Kells.[32] It was suggested by Berthe van Regemorter that in the St Cuthbert Gospel this design represents Christ (as the central bud) and the Four Evangelists as the grapes, following John 15:5, "I am the vine, ye are the branches", but this idea has been treated with caution by other scholars.[33]

The two panels of interlace use the same design, of what David H. Wright describes as the "alternating pair thin-line type" which he calls "perhaps the most sophisticated of Insular interlace types".[31] The panels are symmetrical about a vertical axis, except for the left end of the upper panel, which is different. Whereas the other ends of the pattern finish in a flat line parallel with the vertical framing line, part of a shape like an incomplete D, the top left finishes in two ellipses pointing into the corners. The lines forming the interlace patterns are coloured in the dark blue/black and the bright yellow, but differently. In the lower panel the yellow colours the left half of the design, but the upper panel begins at the (deviant) left in the dark colour, then switches to yellow once the pattern changes to that used for the rest of the panels. It continues in yellow until the central point, then changes to the dark colour for the right hand side of the design.

The transition between the top left, perhaps where the artist began, and the standard pattern, is somewhat awkward, leaving a rather bald spot (for an interlace pattern) to the left of the first curving yellow vertical. The change in pattern pushes the halfway point of the upper panel rather off-centre to the right, whereas in the lower panel it falls slightly to the left of dead centre. These vagaries in the design suggest that it was done freehand, without marking-out the pattern using compasses for example.[34] The lowest horizontal raised line is not straight, being higher at the left, probably because of an error in the marking or drilling of the holes in the cover board through which the ends of the cord run.[35] The simple twist or chain border in yellow between the two raised frames resembles an element in an initial in the Durham Gospel Book Fragment, an important earlier manuscript from Lindisfarne.[36]

Back cover

The back cover is decorated more simply, with no raised elements and purely geometric decoration of engraved lines, which are filled in with two pigments which now appear as the bright yellow and the dark colour, once apparently blue. Within several framing lines making rectangles of similar proportions to the cover itself, a central rectangular panel is marked with pricks to make a grid of 3mm squares, 21 tall and 10 wide. Lines on the grid are engraved and coloured in yellow to form two stepped "crosses", or squares standing on one corner, with additional stepped elements in the four corners and halfway up the vertical sides, between the two "crosses". The vertical axial line down the grid and the two horizontal axes through the crosses are also coloured in the yellow pigment right to the edges of the grid. The remaining lines on the grid and all the lines along the edges of the grid are coloured in the dark colour.[37] This is a simple version of the sort of design found on Insular carpet pages, as well as in Coptic manuscript decoration and textiles, and small stepped crosses decorate the main panels of the famous Sutton Hoo shoulder-clasps.[38] The alignment of the various outer framing lines with the innermost frame and the panel with the grid is noticeably imperfect, as the top framing line was extended too far to the left. Traces of an uncoloured first attempt at this line can be seen on the right hand side, above the coloured line.[39]

Construction

Although the binding had never been taken apart for examination before it was bought by the British Library, a considerable amount can be said about its construction. A combination of looseness through wear and tear, damage in certain places, and the failure of the paste that glued the pages to the inside of the covers, now allow non-intrusive inspection of much of the binding construction, including the rear of the actual wooden front cover board, and some of the holes made through it.[40]

The raised framing lines can be seen from the rear of the front cover to have been produced by gluing cord to the board and tooling the leather over it, in a technique of Coptic origin, of which few early examples survive – one of the closest is a 9th- or 10th-century Islamic binding found in the Mosque of Uqba in Kairouan, Tunisia. There are holes in the board in which the cut-off ends can be seen from behind.[41]

_is_the_oldest_intact_European_book._-_Sewing_(Add_Ms_89000).jpg.webp)

The chalice and plant motif on the front, of which there is no trace from behind, has been built up using some clay-like material underneath the leather, as shown by CT-scans since the purchase. In the 2015 book, Nicholas Pickwoad suggests that this raised decoration was formed using a matrix which was pressed into the damp leather over the clay-like substance and the wooden board. Previous authors had suggested that the material under the relief decoration might have been built up in gesso as well as cord and leather scraps before applying the cover leather.[42] A broadly similar plant motif in similar technique is found on a later Middle Eastern pouch in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.[43]

_is_the_oldest_intact_European_book._-_Headband_(Add_Ms_89000).jpg.webp)

The boards of the covers, previously assumed to be limewood, are now thought to be birch, an unusual wood in later bindings, but one easily available in northern England.[44] Both have four holes where the binding threads were laced through; the two threads were run round the inner edges of the cover and knotted back at the holes. The front cover has an additional 12 holes where the ends of the cords for the raised framing lines went through, at the four corners of the two main frames, and the ends of the horizontal bars between the interlace panels and the central vine motif.[45]

The stitching of the binding uses "Coptic sewing", that is "flexible unsupported sewing (produced by two needles and thread looping round one another in a figure-of-eight sewing pattern)"[46] Coptic sewing uses small threads both to attach the leaves together and, knotted together, to attach the pages to the cover boards. Normal Western binding uses thread for the former and thicker cord running across the spine of the book for the latter, with the thread knotted onto the cords. Coptic sewing is also found in the earliest surviving leather bookbindings, which are from Coptic libraries in Egypt from the 7th and 8th centuries; in particular the design of the cover of one in the Morgan Library (MS M.569) has been compared to the St Cuthbert Gospel.[47] In the techniques used in the binding, apart from the raised decoration, the closest resemblance is to an even smaller Irish pocket gospel book from some 50 years later, the Cadmug Gospels at Fulda, which is believed to have belonged to Saint Boniface. This is also in red goatskin, with coloured incised lines, and uses a similar unsupported or cordless stitching technique. The first appearance of the cords or supports that these "unsupported" bindings lack is found in two other books at Fulda, and they soon became universal in, and characteristic of, Western bookbinding until the arrival of modern machine techniques. The cords run horizontally across the spine, and are thicker than the threads that hold the pages together. They are attached, typically by lacing through holes or glue, to the two boards of the cover, and the threads holding the gatherings are knotted to them, resulting in a stronger binding.[48]

Dating

The manuscript itself carries no date but a rather precise dating has been given to it, based mainly on its palaeography or handwriting, and also the known facts of Cuthbert's burial. The dating was revised after the acquisition by the British Library, who added to their online catalogue entry:

Previously dated to the end of the 7th century (The Stonyhurst Gospel, ed. T. J. Brown (1969), pp. 12–13), R. Gameson dates the script to c. 710–c. 730 and L. Webster dates the decoration on the covers to c. 700–c. 730 (The St Cuthbert Gospel, eds C. Breay and B. Meehan (2015), pp. 33, 80).[49]

The script is the "capitular" form of uncial, with just a few emphasized letters at the start of sections in "text" uncial.[50] Close analysis of the changing style of details of the forms of letters allows the manuscript to be placed with some confidence within a chronological sequence of the few other manuscripts thought to have been produced at Wearmouth-Jarrow. The Northumbrian scribes "imitate very closely the best Italian manuscripts of about the sixth century",[51] but introduced small elements that gave their script a distinct style, which has always been greatly admired. However, there were several scribes, seven different ones working on the Codex Amiatinus, whose scripts may not all have developed at the same pace.[52]

Key to this sequence is the Codex Amiatinus, an almost complete Bible for which we have a very precise terminus ante quem, and within which, because of its size, developments in style can be seen in a single manuscript. The Codex Amiatinus can be precisely located as leaving Wearmouth-Jarrow with a party led by Abbot Ceolfrith on 4 June 716, bound for Rome. The codex was to be presented to Pope Gregory II, a decision only announced by Ceolfrith very shortly before the departure, allowing the dedication page to be dated with confidence to around May 716, though the rest of the manuscript was probably already some years old, but only begun after Ceolfrith succeeded as abbot in 689.[53] The script of the dedication page differs slightly from that of the main text, but is by the same hand and in the same "elaborated text uncial" style as some pages at Durham (MS A II 17, part ii, ff 103-11). At the end of the sequence, it may be possible to date the Saint Petersburg Bede to 746 at the earliest, from references in memoranda in the text, although this remains a matter of controversy.[54]

There survive parts of a gospel book, by coincidence now bound up with the famous Utrecht Psalter, which are identifiable as by the same scribe as the Cuthbert Gospel, and where "the capitular uncial of the two manuscripts is indistinguishable in style or quality, so they may well be very close to each other in date". Since the Utrecht pages also use Rustic capital script, which the Cuthbert Gospel does not, it allows another basis for comparison with further manuscripts in the sequence.[55]

From the palaeographical evidence, T. Julian Brown concluded that the Cuthbert manuscript was written after the main text of the Codex Amiatinus, which was finished after 688, perhaps by 695, though it might be later. Turning to the historical evidence for Cuthbert's burial, this placed it after his original burial in 687 but possibly before his elevation to the high altar in 698. If this is correct, the book was never a personal possession of Cuthbert, as has sometimes been thought, but was possibly created specifically to be placed in his coffin, whether for the occasion of his elevation in 698 or at another date.[56] The less precise hints about dating that can be derived from the style of the binding compared to other works did not conflict with these conclusions,[57] though in the new 2015 study, Leslie Webster now dates the cover to "c. 700–c. 730", and Richard Gameson "dates the script to c. 710–c. 730", as quoted above.

History

Background

Cuthbert was an Anglo-Saxon, perhaps of a noble family, born in the Kingdom of Northumbria in the mid-630s, some ten years after the conversion of King Edwin to Christianity in 627, which was slowly followed by that of the rest of his people. The politics of the kingdom were violent, and there were later episodes of pagan rule, while spreading understanding of Christianity through the kingdom was a task that lasted throughout Cuthbert's lifetime. Edwin had been baptised by Paulinus of York, an Italian who had come with the Gregorian mission from Rome, but his successor Oswald also invited Irish monks from Iona to found the monastery at Lindisfarne where Cuthbert was to spend much of his life. This was around 635, about the time Cuthbert was born.[59]

The tension between the Roman and Irish traditions, often exacerbated by Cuthbert's near-contemporary Saint Wilfrid, an intransigent and quarrelsome supporter of Roman ways, was to be a major feature of Cuthbert's lifetime. Cuthbert himself, though educated in the Irish tradition, followed his mentor Eata in accepting the Roman forms without apparent difficulty after the Synod of Whitby in 664.[60] The earliest biographies concentrate on the many miracles that accompanied even his early life, but he was evidently indefatigable as a travelling priest spreading the Christian message to remote villages, and also well able to impress royalty and nobility. Unlike Wilfrid, his style of life was austere, and when he was able he lived the life of a hermit, though still receiving many visitors.[61]

He grew up near the new Melrose Abbey, an offshoot from Lindisfarne which is today in Scotland, but was then in Northumbria. He had decided to become a monk after seeing a vision on the night in 651 that St Aidan, the founder of Lindisfarne, died, but seems to have seen some military service first. He was quickly made guest-master at the new monastery at Ripon, soon after 655, but had to return with Eata to Melrose when Wilfrid was given the monastery instead.[62] About 662 he was made prior at Melrose, and around 665 went as prior to Lindisfarne. In 684 he was made Bishop of Lindisfarne, but by late 686 he resigned and returned to his hermitage as he felt he was about to die, although he was probably still only in his early 50s. After a few weeks of illness he died on the island on 20 March 687, and his body was carried back to Lindisfarne and buried there the same day.[63]

Lindisfarne

Although first documented in 1104, the book is presumed to have been buried with Cuthbert at Lindisfarne, and to have stayed with the body during the wanderings forced by the Viking invasions two centuries later. Bede's Life recounts that Cuthbert was initially buried in a stone sarcophagus to the right of the altar in the church at Lindisfarne; he had wanted to be buried at the hermitage on Inner Farne Island where he died, but before his death was persuaded to allow his burial at the main monastery.[64] His burial was first disturbed eleven years after his death, when his remains were moved to behind the altar to reflect his recognition, in the days before a formal process of canonisation, as a saint. The sarcophagus was opened and his body was said to have been found perfectly preserved or incorrupt.[65] This apparent miracle led to the steady growth of Cuthbert's posthumous cult, to the point where he became the most popular saint of Northern England.[66]

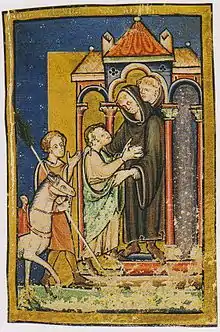

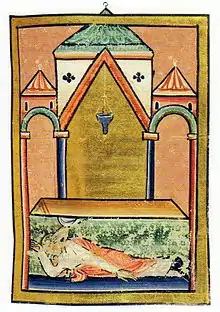

Numerous miracles were attributed to his intercession and to intercessory prayer near his remains. In particular, Alfred the Great, King of Wessex, was inspired and encouraged in his struggle against the Danes by a vision or dream he had of Cuthbert. Thereafter, the royal house of Wessex, who became the kings of England, made a point of devotion to Cuthbert, which also had a useful political message, as they came from opposite ends of the united English kingdom. Cuthbert was "a figure of reconciliation and a rallying point for the reformed identity of Northumbria and England" after the absorption of the Danish populations into Anglo-Saxon society, according to Michelle Brown.[67] The 8th-century historian Bede wrote both a verse and a prose life of St Cuthbert around 720. He has been described as "perhaps the most popular saint in England prior to the death of Thomas Becket in 1170."[68] In 698, Cuthbert was reburied in the decorated oak coffin now usually meant by St Cuthbert's coffin, though he was to have many more coffins.[69] The book was believed to have been produced for this occasion and perhaps placed in his coffin at this time,[70] but according to the new dating it was only created up to 30 years after 698.

Fleeing the Danes

In 793 Lindisfarne was devastated by the first serious Viking raid in England, but Cuthbert's shrine seems to have escaped damage. In 875 the Danish leader Halfdene (Halfdan Ragnarsson), who shared with his brother Ivar the Boneless the leadership of the Great Heathen Army that had conquered much of the south of England, moved north to spend the winter there, as a prelude to settlement and further conquest. Eardulf, the Bishop of Lindisfarne, decided the monastery must be abandoned, and orderly preparations were made for the whole community, including lay people and children, to evacuate.[71]

It was possibly at this point that a shelf or inner cover was inserted some way under the lid of Cuthbert's coffin, supported on three wooden bars across the width, and probably with two iron rings fixed to it for lifting it off.[72] Eardulf had decided to take the most important remains and possessions of the community with them, and whether new or old, the shelf in Cuthbert's coffin was probably loaded with the St Cuthbert Gospel, which was found there in 1104. It may also have held the Lindisfarne Gospels, now also in the British Library, and other books from Lindisfarne that were, and in several cases still are, at Durham Cathedral. Other bones taken by the party were those remains of St Aidan (d. 651), the founder of the community, that had not been sent to Melrose, and the head of the king and saint Oswald of Northumbria, who had converted the kingdom and encouraged the founding of Lindisfarne. These and other relics were reverently packaged in cloth and labelled, as more recent relics are. The community also took a stone Anglo-Saxon cross, and although they had a vehiculum of some sort, probably a cart or simple wagon, Cuthbert's coffin was carried by seven young men who had grown up in the community.[73]

They set off inland and spent the first months at an unknown location in west Cumberland, near the River Derwent, probably in the modern Lake District, and according to Symeon of Durham's Libellus de exordio, the main source for this period, Eardulf tried to hire a ship on the west coast to take them to Ireland. Then they left the more remote west side of the country and returned to the east, finding a resting-place at Craike near Easingwold, close to the coast, well south of Lindisfarne, but also sufficiently far north of the new Viking kingdom being established at York.

Over the next century the Vikings of York and the north became gradually Christianized, and Cuthbert's shrine became a focus of devotion among them also. The community established close relations with Guthred (d. 895), Halfdene's successor as king, and received land from him at Chester-le-Street. In 883 they moved the few miles there, where they stayed over a century, building St Cuthbert's Church, where Cuthbert's shrine was placed. In 995 a new Danish invasion led the community to flee some 50 miles south to Ripon, again taking the coffin with them. After three or four months it was felt safe to return, and the party had nearly reached Chester-le-Street when their wagon became definitively stuck close to Durham, then a place with cultivated fields, but hardly a settlement, perhaps just an isolated farm. It was thought that Cuthbert was expressing a wish to settle where he was, and the community obeyed. A new stone church—the so-called White Church—was built, the predecessor of the present Durham Cathedral.[74]

Durham Cathedral

In 1104, early in the bishopric of Ranulf Flambard, Cuthbert's tomb was opened again and his relics translated to a new shrine behind the main altar of the half-built Norman cathedral. According to the earlier of the two accounts of the event that survive, known as "Miracles 18–20" or the "anonymous account", written by a monk of the cathedral, when the monks opened the decorated inner coffin, which was for the first time in living memory, they saw "a book of the Gospels lying at the head of the board", that is on the shelf or inner lid.[75] The account in "Miracle 20" adds that Bishop Flambard, during his sermon on the day the new shrine received Cuthbert's body, showed the congregation "a Gospel of Saint John in miraculously perfect condition, which had a satchel-like container of red leather with a badly frayed sling made of silken threads".[76] In addition the book itself has an inscription on folio 1r "written in a modest book-hand apparently of the later twelfth century" recording that it was found in the translation.[77]

As far as is known the book remained at Durham for the remainder of the Middle Ages, until the Dissolution, kept as a relic in three bags of red leather, normally resting in a reliquary, and there are various records of it being shown to visitors, the more distinguished of which were allowed to hang it round their neck for a while. According to Reginald of Durham (d. c 1190) "anyone approaching it should wash, fast and dress in an alb before touching it", and he recorded that a scribe called John who failed to do this during a visit by the Archbishop of York in 1153–54, and "held it with unwashed hands after eating was struck down with a chill".[78] Books treated as relics are especially characteristic of Celtic Christianity; several of the surviving Irish book-shrines were worn in this way.[79]

Another recorded copy of the Gospel of John has also been associated with Cuthbert, and sometimes thought to be the St Cuthbert Gospel. Saint Boisil (d. 664) of Melrose Abbey was Cuthbert's teacher. Bede's prose life of Cuthbert records that during Boisil's last illness, he and Cuthbert read daily one of the seven gatherings or quaternions of Boisil's manuscript of the Gospel of John.[80] The sermon in Miracle 20 identifies this manuscript with the one at Durham, and says that both saints had worn it round their necks, ignoring that it has twelve gatherings rather than seven. There are further references from Durham to Boisil's book, such as a list of relics in the cathedral in 1389, and some modern scholars were attracted to the idea that they were the same,[81] but Brown's palaeographical evidence seems to remove the possibility of Boisil's book being the St Cuthbert Gospel. In the 11th century Boisil's remains had also been brought to Durham, and enshrined next to those of Cuthbert. Around the same time Bede's own remains were stolen from Monkwearmouth–Jarrow for Durham, by a "notably underhand trick", and placed in Cuthbert's coffin, where they remained until 1104.[82]

After the Reformation

It is thought likely that the book remained at Durham until the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII, although the various late medieval records of books and relics held there do not allow it to be identified with certainty.[83] Durham Cathedral Priory closed in 1540, and some decades later the book was recorded by Archbishop Ussher in the library of the Oxford scholar, antiquary and astrologer Thomas Allen (1542–1632) of Gloucester Hall (now Worcester College, Oxford). However it is not in a catalogue of Allen's library of 1622, and was not in the collection of Allen's manuscripts that was presented to the Bodleian Library by Sir Kenelm Digby in 1634. Nothing is then known of its whereabouts for a century or so.[84]

According to an 18th-century Latin inscription pasted to the inside cover of the manuscript, the St Cuthbert Gospel was given by the 3rd Earl of Lichfield (1718–1772) to the Jesuit priest Thomas Phillips S.J. (1708–1774) who donated it to the English Jesuit College at Liège on 20 June 1769. Lichfield was an Anglican, but knew Phillips as the latter was chaplain to his neighbour in Oxfordshire, the recusant George Talbot, 14th Earl of Shrewsbury (1719–1787).[85] The manuscript was owned between 1769 and 2012 by the British Province of the Society of Jesus, and for most of this period was in the library of Stonyhurst College, Lancashire, successor to the Liège college.[86]

The manuscript was first published when in 1806 it was taken to London and displayed when a letter on it by the Rev. J. Milner, presumably Bishop John Milner, Catholic Vicar Apostolic of the Midland District, was read to a meeting of the London Society of Antiquaries, which was subsequently printed in their journal Archaeologia.[87] Milner followed the medieval note in relating the book to Cuthbert, and compared its script to that of the Lindisfarne Gospels, by then in the British Museum, examining the two side by side. However he thought that "the binding seems to be of the time of Queen Elizabeth"![88] After the lecture it took some years to return to Stonyhurst as an intermediary forgot to forward it.[89] That the binding was original, and the earliest European example, was realised during the 19th century, and when exhibited in 1862 it was described in the catalogue as "In unique coeval (?) binding".[90] The whole appearance and feel of the book, and the accuracy of the text and beauty of the script was highly praised by scholars such as Bishop Christopher Wordsworth (1807–1885), nephew of the poet and an important New Testament textual scholar, who described the book as "surpassing in delicate simplicity of neatness every manuscript that I have seen".[91]

From 1950

_is_the_oldest_intact_European_book._-_Fore_edge_(Add_Ms_89000).jpg.webp)

From 1950 onwards the binding was examined several times, but not altered, at Stonyhurst and the British Museum by Roger Powell, "the leading bookbinder of his day", who had rebound both the Book of Kells and the Book of Durrow,[92] and also fully photographed by Peter Walters.[93] Powell contributed chapters on the binding to the two major works covering the book, the first being The Relics of St Cuthbert in 1956, a large work with chapters on Cuthbert's coffin and each of the objects recovered from it. The main chapter on the St Cuthbert Gospel was by Sir Roger Mynors, and Powell's chapter incorporated unpublished observations by the leading bindings expert Geoffrey Hobson.[94] The second came in 1969, when T.J. (Julian) Brown, Professor of Palaeography at King's College, London, published a monograph on the St Cuthbert Gospel with another chapter by Powell, who had altered his views in minor respects. Brown set out arguments for the dating of the manuscript to close to 698, which has been generally accepted. The book was placed on loan to the British Library in 1979 where it was very regularly on display, first in the British Museum building, and from 1999 in the Ritblat Gallery at the new St Pancras site of the Library, usually displaying the front cover. Despite minor damages, some of which appear to have occurred during the 20th century, the book is in extremely good condition for its age.[95]

In 2011 an agreement was reached with the Jesuit British Province for the British Library to buy the book for £9 million. This required the purchase money to be raised by 31 March 2012, and a public appeal was launched. In the early stages the emphasis was on raising large individual donations, which included £4,500,000 from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, which distributes some of the money from the profits of the National Lottery,[96] £250,000 pledged by the Art Fund,[97] and "a similar sum" by The Garfield Weston Foundation,[98] and a large gift from the Foyle Foundation.[99] By early March 2012 the British Library reported that there was "only £1.5M left to raise",[100] and on 17 April announced that the purchase had been completed, after their largest ever public appeal. The purchase "involved a formal partnership between the Library, Durham University and Durham Cathedral and an agreement that the book will be displayed to the public equally in London and the North East." There was a special display at the British Library until June 2012, and after coming off display for detailed investigation the book went on display in Durham in July 2013 in Durham University's Palace Green Library. Subsequently it has been on display in both London and Durham, but with periods "resting" off display. All the pages are accessible on the British Library website.[101]

The Gospel of John as an amulet

There was a long and somewhat controversial tradition of using manuscripts of the Gospel of John, or extracts such as the opening verse, as a protective or healing amulet or charm, which was especially strong in early medieval Britain and Ireland. Manuscripts containing the text of one gospel only are very rare, except for those with lengthy explanatory glosses, and all the examples known to Julian Brown were of John.[102] Disapproving references to such uses can be found in the writings of Saints Jerome and Eligius, and Alcuin, but they are accepted by John Chrysostom, Augustine, who "expresses qualified approval" of using manuscripts as a cure for headaches, and Gregory the Great, who sent one to Queen Theodelinda for her son.[103] Bede's prose Life mentions that Cuthbert combated the use of amulets and charms in the villages around Melrose.[104] However, like many other leading figures of the church, he may have distinguished between amulets based on Christian texts and symbols and other types.[105]

The size of the Cuthbert Gospel places it within the Insular tradition of the "pocket gospels", of which eight Irish examples survive,[106] including the Book of Dimma, Book of Mulling, and Book of Deer, although all the others are or were originally texts of all four gospels, with the possible exception of a few pages from the Gospel of John enshrined with the Stowe Missal in its cumdach or book-reliquary. There was a tradition of even smaller books, whose use seems to have been often amuletic, and a manuscript of John alone, with a page size of 72 x 56 mm, was found in a reliquary at Chartres Cathedral in 1712. It is probably Italian from the 5th or 6th century, and the label it carried in 1712 saying it was a relic of St Leobinus, a bishop of Chartes who died in about 556, may be correct. The other examples are mostly in Greek or the Coptic language and contain a variety of biblical texts, especially psalters. Julian Brown concludes that the three Latin manuscripts of John "seem to attest an early medieval practice of placing a complete Gospel of St. John in a shrine, as a protective amulet; and it seems reasonable to conclude that our manuscript was placed in St. Cuthbert's coffin to protect it".[107]

Exhibitions

Apart from being usually on display at the British Museum and British Library (see above), the book has been in the following exhibitions ( * denotes that there was a detailed published catalogue):

- 1862, Victoria & Albert Museum, Loan Exhibition[108]

- 1930, Victoria & Albert Museum, Medieval English Art *

- 1987, Durham Cathedral Treasury, An exhibition of manuscripts brought together at Durham to celebrate the saint's 1300th anniversary and the work of his early community

- 1991, British Museum, The Making of England: Anglo-Saxon Art and Culture AD 600–900 *

- 1996, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, Treasures from the Lost Kingdom of Northumbria

- 1997, British Museum, The Heirs of Rome: The Shaping of Britain AD 400–900, part of the series The Transformation of the Roman World Ad 400–900 *

- 2003, British Library, Painted Labyrinth: The World of the Lindisfarne Gospels *

- 2007, British Library, Sacred: Discover What We Share

- 2013 Palace Green Library, Durham University, in an exhibition which also included the Lindisfarne Gospels, items from the Staffordshire Hoard, the Yates Thompson 26 Life of Cuthbert (from which several illustrations here are taken), and the gold Taplow belt buckle.[109]

- 2014, Palace Green Library, Durham, "Book binding from the Middle Ages to the modern day".[110]

- 2018/19 British Library, "Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War" *[111]

A digital version[112] of the manuscript was produced to run on an Apple iPad,[113] which was exhibited in April 2012 at the British Library.

Notes

- "St Cuthbert Gospel Saved for the Nation", British Library Medieval and Earlier Manuscripts Blog, accessed 17 April 2012

- British Library press release, "British Library announces £9m campaign to acquire the St Cuthbert Gospel – the earliest intact European book", 13 July 2011, with good photos of the cover, and a video. Accessed 8 March 2012

- British Library, Digitized Manuscripts page, on the binding: Battiscombe, throughout Powell's section, 362–373; Brown (1969), 46–55

- Needham, 55–57

- Avrin, 310–311: Brown (2003), 66–69 on "book icons".

- Brown (2003), 208–210

- Needham, 55–60; Marks, 6–7; Avrin, 309–311

- Brown (1969), 6, 24–25, 61–62

- Brown (1969), 21, 61–62; in analysis after British Library purchase, the pigment for the red initials was identified as red lead.

- Wilson, 30

- Brown (1969), 59

- Brown (1969), 58–59; Battiscombe, 356

- Brown (1969), 25–26

- Brown (1969), 43–44

- Brown (2007), 16; Marks, 20. The leather cover of the Irish Faddan More Psalter, of about 800 and discovered in 2006, is an interesting comparison, but apparently only decorated as a trial piece.

- Regemorter, 45

- Calkins, 53, 61–62

- Wilson, 32–33; Calkins, 57–60

- Brown (1969), 16–18, who makes a number of specific comparisons; Wright, 154

- BL online page, "The lines of the left board are filled in yellow (orpiment) and grey-blue (indigo)". This is covered in the 2015 book

- Brown (1969), 14–21

- Battiscombe, 370

- Regemorter, 44–45

- Stevick, 9–18

- Brown (1969), 22, 57 (quote); Bonner, 237; 296-8; Brown (2003), 209

- "The left board is decorated with a rectangular frame with interlace patterns in the upper and lower fields and a larger central field containing a chalice from which stems project, terminating in a leaf or bud and four fruits" describes the BL online catalogue in 2015. Previously, eg in Battiscombe, 372, the chalice was not mentioned.

- Wilson, 63–67; 70–77

- Brown (1969), 21; illustrated at Wilson, 50, and in the chapter on it in Battiscombe.

- Brown (1969), 21

- Calkins, 61–62; Meehan, 25

- Wright, 154

- Schapiro, 224, note 82, comparing with Kells f 94, his figure 17 at page 216

- Regemorter, 45; Brown (1969), 21; Battiscombe, 373

- Battiscombe, 373; Brown (1969), 15–16

- Stevick, 11–12

- Battiscombe, 372. The chain runs down the centre of the two large verticals of the INI "monogram" on f2; it is illustrated at Brown (2007), 25.

- Brown (1969), 14–15; colour photo of back cover, British Library Database of Bookbindings, accessed 3 March 2012

- Wright, 154–155; Battiscombe, 372; Photo of the Sutton Hoo shoulder clasps

- Stevick, 15–18

- Battiscombe, throughout Powell's section, 362–373; Brown (1969), 46–55

- Battiscombe, 367–368; Wright, 154; Jones and Michell, 319; Szirmai, 96

- Bloxham & Rose; Brown (1969), 16 and note, suggesting the use of leather; Nixon and Foot, 1, suggesting gesso and cords.

- Wright, 153–154

- Brown (1969), 46; Battiscombe, 364. The identification as birch was first made by "Mr Embley, master-joiner at Stonyhurst" for Hobson, confirmed by samples and advice from the Forest Products Research Laboratory at Princes Risborough.

- Battiscombe, 367–368

- Brown (2007), 16, quoted; Brown (1969), 47–49

- Avrin, 309–310; Morgan Library, MS M.569, accessed 8 March 2012

- Marks, 8–10; Needham, 58; Avrin, 309–310; Szirmai, 95–97

- British Library Digitized manuscripts site, accessed 12 June 2015. see Further reading for the 2015 book

- Brown (1969), 6–7; 62

- Brown (1969), 6

- Brown (1969), 11–13: see also Wilson, 30–32

- Brown (1969), 9–11

- Brown (1969), 8, 13. Brown in 1969 accepted the arguments for the 746 dating. Quote re Durham page 8.

- Brown (1969), 7–8, 10; p. 8 quoted

- Brown (1969), 9–11, 28

- Brown (1969), 13–23

- British Library Archived 2011-12-16 at the Wayback Machine, Detailed record for Yates Thompson 26, accessed 8 March 2012

- Battiscombe, 115–116

- Battiscombe, 122–129; Farmer, 53–54, 60–66; Brown (2003), 64–66. At least Bede records no reluctance, though Farmer and others suspect he may be being less than frank in this, as a partisan of Jarrow.

- Battiscombe, 115–141; Farmer, 52–53, 57–60

- Battiscombe, 120–125; Farmer, 57

- Battiscombe, 125–141; Farmer, 60

- Bede, Chapters 37 and 40

- Battiscombe, 22–24; Bede, Chapter 42

- Farmer, 52–53; 68

- Battiscombe, 31–34; Brown (2003), 64 (quoted)

- Marner, 9, quoted; Farmer, 52–53

- Cronyn and Horie, 5–7, are the easiest guide to this very complicated history, or see Battiscombe, 2–22 and Ernst Kitzinger's chapter on the coffin; Bede, chapter 42 is the primary source

- Brown (1969), 28, 41–44

- Battiscombe, 25–28

- Cronyn & Horie, x, 4, 6–7; Battiscombe, 7, and the chapter on the coffin. Brown (1969), 28, thinks it more likely that the shelf was part of the original design from 698. Kitzinger, in Battiscombe, 217 n., seems indifferent. Two iron rings are mentioned in the early sources, but their precise location and function is unclear.

- Battiscombe, 27–28

- Battiscombe, 28–36

- Brown (1969), 2–3. The account uses the plural "gospels", which has caused a great deal of discussion. The majority of scholars who believe this to refer to the St Cuthbert Gospel take this as a slip by a chronicler writing some years after the event.

- Brown (1969), 3

- Brown (1969), 2

- Bonner, 460; Brown (1969), 4–5

- Brown (2003), 69–72, 210–211

- Bede, Ch. VIII

- Brown (1969), 4–5

- Brown (1969), 28

- Brown (1969), 1–2, 5. It seems probable that it was one of two books listed in 1383. See also Brown (2003) and Janet Backhouse's 1981 book on the Lindisfarne Gospels for more details on the Durham records and the various other gospel books that might be referred to.

- Brown (1969), 1–2. Intriguingly, Allen was an undergraduate at Trinity College, Oxford, which was on the former site of Durham College, Oxford, a cell of the Durham Cathedral Benedictines for their students. Gloucester Hall had also been the main college for Benedictine monks at Oxford. See "Houses of Benedictine monks: Durham College, Oxford", in A History of the County of Oxford, Volume 2, 1907, pp. 68–70, on British History Online, accessed 27 March 2012.

- Brown (1969), 1; Battiscombe, 360–361. Lichfield lived at Ditchley Park and Shrewsbury at Heythrop Hall, some 5 miles away.

- Brown (1969), 1

- Milner; Battiscombe, 362

- Milner, 19–21, 20 quoted; Brown (1969), 45; Battiscombe, 362

- "The case of the missing Gospel", Daily Telegraph story by Christopher Howse, 16 June 2007, reporting an article by Michelle Brown. Accessed 2 March 2012

- Weale, xxii, who in 1898 was sure it was the earliest.

- Quoted in Battiscombe, 358; Brown (1969), 45–46

- Meehan, 74–76, 74 quoted

- Battiscombe, 362–363

- All referenced here as Battiscombe

- Battiscombe, 362–368; Brown (1969), 45–55, 59

- NHMF Press release Archived 26 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine , 14 July 2011, accessed 28 February 2012

- Art Fund website Archived 7 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine , British Library campaigns to buy the earliest intact European book, accessed 9 October 2011

- British Library, Medieval and Earlier Manuscripts blog, accessed 24 February 2012; a breakdown of the funding from The Economist, as at July 2011, can be seen here

- BL Press release on purchase, see next ref.

- Support the BL, accessed 12 March 2012

- See first external link; "British Library acquires the St Cuthbert Gospel – the earliest intact European book", BL Press release, accessed 17 April 2012

- Brown (1969), 29–31, 35–37

- Brown (1969), 30; Skemer's subject is the wider use of textual amulets of all sorts

- Bede, Ch 9; Skemer, 50–51

- Skemer, 50–58

- Szirmai, 97, following McGurk

- Brown (1969), 32–36, 33 quoted

- Weale, xxii

- "Lindisfarne Gospels exhibition website". Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- Friends of Palace Green Library, "Events", accessed 7 December 2013.

- BL blog, 20 May 2020, "Remembering Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War" by Claire Breay

- "Digitised Manuscripts - Add MS 8900". British Library. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- "St Cuthbert Gospel iPad version". Clay Interactive Ltd. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

References

- Avrin, Leila, Scribes, Script, and Books, revised edn. 2010 (1st edn. 1991), ALA Editions, ISBN 0-8389-1038-6, ISBN 978-0-8389-1038-2, google books

- Battiscombe, C. F. (ed), The Relics of Saint Cuthbert, Oxford University Press, 1956, including R. A. B. Mynors and R. Powell on 'The Stonyhurst Gospel'

- Bede, Prose Life of Saint Cuthbert, written c. 721, online English text from Fordham University

- Bloxham, Jim & Rose, Kristine; St. Cuthbert Gospel of St. John, Formerly Known as the Stonyhurst Gospel, a summary of a lecture by two specialist bookbinders from Cambridge University given to the Guild of Bookworkers, New York Chapter in 2009, accessed 8 March 2012 (see also external links section below)

- Bonner, Gerald, Rollason, David & Stancliffe, Clare, eds., St. Cuthbert, his Cult and his Community to AD 1200, 1989, Boydell and Brewer, ISBN 978-0-85115-610-1

- Brown (1969); Brown, T. J. (Julian), et al., The Stonyhurst Gospel of Saint John, 1969, Oxford University Press, printed for the Roxburghe Club (reproduces all pages)

- Brown (2003), Brown, Michelle P., The Lindisfarne Gospels: Society, Spirituality and the Scribe, 2003, British Library, ISBN 978-0-7123-4807-2

- Brown (2007); Brown, Michelle P., Manuscripts from the Anglo-Saxon Age, 2007, British Library, ISBN 978-0-7123-0680-5

- Calkins, Robert G. Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages, 1983, Cornell University Press, ISBN 0-500-23375-6

- Cronyn, J. M., Horie, Charles Velson, St. Cuthbert's coffin: the history, technology & conservation, 1985, Dean and Chapter, Durham Cathedral, ISBN 0-907078-18-4, ISBN 978-0-907078-18-0

- Farmer, David Hugh, Benedict's Disciples, 1995, Gracewing Publishing, ISBN 0-85244-274-2, ISBN 978-0-85244-274-6, google books

- Jones, Dalu, Michell, George, (eds); The Arts of Islam, 1976, Arts Council of Great Britain, ISBN 0-7287-0081-6

- Marks, P. J. M., Beautiful Bookbindings, A Thousand Years of the Bookbinder's Art, 2011, British Library, ISBN 978-0-7123-5823-1

- Marner, Dominic, St. Cuthbert: His Life and Cult in Medieval Durham, 2000, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0-8020-3518-3

- Meehan, Bernard, The Book of Durrow: A Medieval Masterpiece at Trinity College Dublin, 1996, Town House Dublin, ISBN 978-1-86059-006-1

- Milner, John, "Account of an Ancient Manuscript of the St John's Gospel", in Archaeologia, Volume xvi (1812), pages 17–21 online text, accessed 3 March 2012

- Needham, Paul, Twelve Centuries of Bookbindings 400–1600, 1979, Pierpont Morgan Library/Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-211580-5

- Schapiro, Meyer, Selected Papers, volume 3, Late Antique, Early Christian and Mediaeval Art, 1980, Chatto & Windus, ISBN 0-7011-2514-4

- Regemorter, Berthe van, Binding Structures in the Middle Ages, (translated by J. Greenfield), 1992, Bibliotheca Wittockiana, Brussels

- Skemer, Don C., Binding Words: Textual Amulets in the Middle Ages, Penn State Press, 2006, ISBN 0-271-02722-3, ISBN 978-0-271-02722-7, Google books

- Stevick, Robert D., "The St. Cuthbert Gospel Binding and Insular Design", Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 8, No. 15 (1987), JSTOR

- Szirmai, J. A., The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding, 1999, Ashgate, ISBN 978-0-85967-904-6

- Weale, W. H. J., Bookbindings and Rubbings of Bindings in the National Art Library South Kensington, 1898, Eyre and Spottiswoode for HMSO

- Wilson, David M., Anglo-Saxon Art: From The Seventh Century To The Norman Conquest, 1984, Thames and Hudson (US edn. Overlook Press)

- Wright, David H., review of Battiscombe (1956), The Art Bulletin, Vol. 43, No. 2 (June 1961), pp. 141–160, JSTOR

Further reading

- Breay, Clare and Meehan, Bernard (eds), The St Cuthbert Gospel: Studies on the Insular Manuscript of the Gospel of John, 2015, British Library, ISBN 978-0-7123-5765-4, "scholarly pieces on Cuthbert in his historical context; the codicology, text, script and medieval history of the manuscript; the structure and decoration of the binding; the other relics found in Cuthbert's coffin; and the post-medieval ownership of the book".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St Cuthbert Gospel (c.698) - BL Add MS 89000. |

- British Library Digitized manuscripts site, with images of all pages

- "Getting Under the Covers of the St Cuthbert Gospel", BL blogpost, 25 June 2015, by Clare Breay, covering recent testing results

- British Library appeal campaign video, 4.55 minutes, with good views of the manuscript

- A shorter BBC video, 1.22 minutes, with the curator

- BBC Radio 4: 3 January 2012 episode of In Our Time with Melvyn Bragg and guests including Claire Breay of the British Library. The St Cuthbert Gospel is discussed between 8:40 and 14:10 of a 30-minute recording.

- British Library press release on the work and its background and acquisition, by Claire Breay

- More information at Earlier Latin Manuscripts