Iona

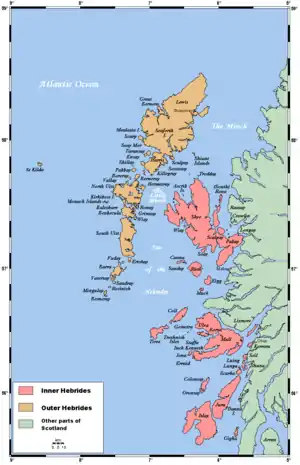

Iona (Scottish Gaelic: Ì Chaluim Chille (IPA:[ˈiːˈxaɫ̪ɯimˈçiʎə]), sometimes simply Ì; Scots: Iona) is a small island in the Inner Hebrides off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though there are other buildings on the island. Iona Abbey was a centre of Gaelic monasticism for three centuries[4] and is today known for its relative tranquility and natural environment.[7] It is a tourist destination and a place for spiritual retreats. Its modern Scottish Gaelic name means "Iona of (Saint) Columba" (formerly anglicised "Icolmkill").

| Scottish Gaelic name | Ì Chaluim Chille |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | [iː xalˠ̪əmˈçiʎə] ( |

| Scots name | Iona[1] |

| Old Norse name | Eyin Helga; Hioe (hypothetical) |

The Abbey as seen from the sea | |

| Location | |

Iona Iona shown within Argyll and Bute | |

| OS grid reference | NM275245 |

| Coordinates | 56°19′48″N 06°24′36″W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Mull |

| Area | 877 ha (3 3⁄8 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 56 [2] |

| Highest elevation | Dùn Ì, 101 m (331 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Argyll and Bute |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 177[3] |

| Population rank | 35 [2] |

| Largest settlement | Baile Mór |

| References | [4][5][6] |

One report summarizes the religious aspect of the island as: "known as the birthplace of Celtic Christianity in Scotland. St Columba came here in the year 563 to establish the Abbey which still stands".[8]

Etymology

The Hebrides have been occupied by the speakers of several languages since the Iron Age, and as a result many of the names of these islands have more than one possible meaning.[9] Nonetheless few, if any, can have accumulated as many different names over the centuries as the island now known in English as "Iona".

The earliest forms of the name enabled place-name scholar William J. Watson to show that the name originally meant something like "yew-place".[10] The element Ivo-, denoting "yew", occurs in Ogham inscriptions (Iva-cattos [genitive], Iva-geni [genitive]) and in Gaulish names (Ivo-rix, Ivo-magus) and may form the basis of early Gaelic names like Eógan (ogham: Ivo-genos).[11][fn 1] It is possible that the name is related to the mythological figure, Fer hÍ mac Eogabail, foster-son of Manannan, the forename meaning "man of the yew".[12]

Mac an Tàilleir (2003) lists the more recent Gaelic names of Ì,[fn 2] Ì Chaluim Chille and Eilean Idhe noting that the first named is "generally lengthened to avoid confusion" to the second, which means "Calum's (i.e. in latinised form "Columba's") Iona" or "island of Calum's monastery".[13][14] The confusion results from ì, despite its original etymology as the name of the island, being confused with the Gaelic noun ì "island" (now obsolete) of Old Norse origin (ey "island",[15][16] Eilean Idhe means "the isle of Iona", also known as Ì nam ban bòidheach ("the isle of beautiful women"). The modern English name comes of yet another variant, Ioua,[13][14] which was either just Adomnán's attempt to make the Gaelic name fit Latin grammar or else a genuine derivative from Ivova ("yew place").[17] Ioua's change to Iona, attested from c.1274,[18] results from a transcription mistake resulting from the similarity of "n" and "u" in Insular Minuscule.[19]

Despite the continuity of forms in Gaelic between the pre-Norse and post-Norse eras, Haswell-Smith (2004) speculates that the name may have a Norse connection, Hiōe meaning "island of the den of the brown bear".[14] The medieval English language version was "Icolmkill" (and variants thereof).[14]

| Table of earliest forms (incomplete) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form | Source | Language | Notes | |

| Ioua insula | Adomnán's Vita Columbae (c. 700) | Latin | Adomnán calls Eigg Egea insula and Skye Scia insula | |

| Hii, Hy | Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum | Latin | ||

| Eoa, Iae, Ie, I Cholaim Chille |

Annals of Ulster | Irish, Latin | U563 Nauigatio Coluim Chille ad Insolam Iae "The journey of St Columba to Í" U716 Pascha comotatur in Eoa ciuitate "The date of Easter is changed in the monastery of Í")[20] U717 Expulsio familie Ie "The expulsion of the community of Í" U778 Niall...a nn-I Cholaim Chille "Niall... in Í Cholaim Chille" | |

| Hi, Eu | Lebor na hUidre | Irish | Hi con ilur a mmartra "Hi with the multitude of its relics" in tan conucaib a chill hi tosuċ .i. Eu "the time he raised his church first i.e. Eu" | |

| Eo | Walafrid Strabo (c. 831) | Latin | Insula Pictorum quaedam monstratur in oris fluctivago suspensa salo, cognominis Eo "On the coasts of the Picts is pointed out an isle poised in the rolling sea, whose name is Eo"[21] | |

| Euea insula | Life of St Cathróe of Metz | Latin | ||

Folk etymology

Murray (1966) claims that the "ancient" Gaelic name was Innis nan Druinich ("the isle of Druidic hermits") and repeats a Gaelic story (which he admits is apocryphal) that as Columba's coracle first drew close to the island one of his companions cried out "Chì mi i" meaning "I see her" and that Columba's response was "Henceforth we shall call her Ì".[22]

Geology

The geology of Iona is quite complex given the island's size and quite distinct from that of nearby Mull. About half of the island's bedrock is Scourian gneiss assigned to the Lewisian complex and dating from the Archaean eon making it some of the oldest rock in Britain and indeed Europe. Closely associated with these gneisses are mylonite and meta-anorthosite and melagabbro. Along the eastern coast facing Mull are steeply dipping Neoproterozoic age metaconglomerates, metasandstones, metamudstones and hornfelsed metasiltstones ascribed to the Iona Group, described traditionally as Torridonian. In the southwest and on parts of the west coast are pelites and semipelites of Archaean to Proterozoic age. There are small outcrops of Silurian age pink granite on southeastern beaches, similar to those of the Ross of Mull pluton cross the sound to the east. Numerous geological faults cross the island, many in a E-W or NW-SE alignment. Devonian aged microdiorite dykes are found in places and some of these are themselves cut by Palaeocene age camptonite and monchiquite dykes ascribed to the 'Iona-Ross of Mull dyke swarm’. More recent sedimentary deposits of Quaternary age include both present day beach deposits and raised marine deposits around Iona as well as some restricted areas of blown sand.[23][24]

Geography

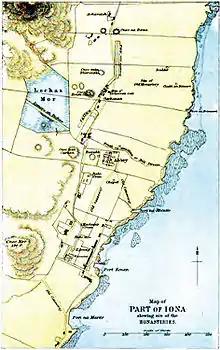

_by_John_Bartholomy_1874.jpg.webp)

*Ceann Tsear *Sliabh Meanach *Machar *Sliginach *Sliabh Siar *Staonaig

Iona lies about 2 kilometres (1 mile) from the coast of Mull. It is about 2 km (1 mi) wide and 6 km (4 mi) long with a resident population of 125.[25] Like other places swept by ocean breezes, there are few trees; most of them are near the parish church.

Iona's highest point is Dùn Ì, 101 m (331 ft), an Iron Age hill fort dating from 100 BC – AD 200. Iona's geographical features include the Bay at the Back of the Ocean and Càrn Cùl ri Éirinn (the Hill/Cairn of [turning the] Back to Ireland), said to be adjacent to the beach where St. Columba first landed.

The main settlement, located at St. Ronan's Bay on the eastern side of the island, is called Baile Mòr and is also known locally as "The Village". The primary school, post office, the island's two hotels, the Bishop's House and the ruins of the Nunnery are here. The Abbey and MacLeod Centre are a short walk to the north.[5][26] Port Bàn (white port) beach on the west side of the island is home to the Iona Beach Party.[27]

There are numerous offshore islets and skerries: Eilean Annraidh (island of storm) and Eilean Chalbha (calf island) to the north, Rèidh Eilean and Stac MhicMhurchaidh to the west and Eilean Mùsimul (mouse holm island) and Soa Island to the south are amongst the largest.[5] The steamer Cathcart Park carrying a cargo of salt from Runcorn to Wick ran aground on Soa on 15 April 1912, the crew of 11 escaping in two boats.[28][fn 3]

Subdivision

On a map of 1874, the following territorial subdivision is indicated (from north to south):[29]

- Ceann Tsear

- Sliabh Meanach

- Machar

- Sliginach

- Sliabh Siar

- Staonaig

History

Dál Riata

In the early Historic Period Iona lay within the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata, in the region controlled by the Cenél Loairn (i.e. Lorn, as it was then). The island was the site of a highly important monastery (see Iona Abbey) during the Early Middle Ages. According to tradition the monastery was founded in 563 by the monk Columba, also known as Colm Cille, who had been exiled from his native Ireland as a result of his involvement in the Battle of Cul Dreimhne.[30] Columba and twelve companions went into exile on Iona and founded a monastery there. The monastery was hugely successful, and played a crucial role in the conversion to Christianity of the Picts of present-day Scotland in the late 6th century and of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria in 635. Many satellite institutions were founded, and Iona became the centre of one of the most important monastic systems in Great Britain and Ireland.[31]

Iona became a renowned centre of learning, and its scriptorium produced highly important documents, probably including the original texts of the Iona Chronicle, thought to be the source for the early Irish annals.[31] The monastery is often associated with the distinctive practices and traditions known as Celtic Christianity. In particular, Iona was a major supporter of the "Celtic" system for calculating the date of Easter at the time of the Easter controversy, which pitted supporters of the Celtic system against those favoring the "Roman" system used elsewhere in Western Christianity. The controversy weakened Iona's ties to Northumbria, which adopted the Roman system at the Synod of Whitby in 664, and to Pictland, which followed suit in the early 8th century. Iona itself did not adopt the Roman system until 715, according to the Anglo-Saxon historian Bede. Iona's prominence was further diminished over the next centuries as a result of Viking raids and the rise of other powerful monasteries in the system, such as the Abbey of Kells.[31][32]

The Book of Kells may have been produced or begun on Iona towards the end of the 8th century.[31][33] Around this time the island's exemplary high crosses were sculpted; these may be the first such crosses to contain the ring around the intersection that became characteristic of the "Celtic cross".[31] The series of Viking raids on Iona began in 794 and, after its treasures had been plundered many times, Columba's relics were removed and divided two ways between Scotland and Ireland in 849 as the monastery was abandoned.[34]

Kingdom of the Isles

As the Norse domination of the west coast of Scotland advanced, Iona became part of the Kingdom of the Isles. The Norse Rex plurimarum insularum Amlaíb Cuarán died in 980 or 981 whilst in "religious retirement" on Iona.[35][36] Nonetheless the island was sacked twice by his successors, on Christmas night 986 and again in 987.[37] Although Iona was never again important to Ireland, it rose to prominence once more in Scotland following the establishment of the Kingdom of Scotland in the later 9th century; the ruling dynasty of Scotland traced its origin to Iona, and the island thus became an important spiritual centre for the new kingdom, with many of its early kings buried there.[31] However, a campaign by Magnus Barelegs led to the formal acknowledgement of Norwegian control of Argyll, in 1098.

Somerled, the brother-in-law of Norway's governor of the region (the King of the Isles), launched a revolt, and made the kingdom independent. A convent for Augustinian nuns was established in about 1208, with Bethóc, Somerled's daughter, as first prioress. The present buildings are of the Benedictine abbey, Iona Abbey, from about 1203, dissolved at the Reformation.

On Somerled's death, nominal Norwegian overlordship of the Kingdom was re-established, but de facto control was split between Somerled's sons, and his brother-in-law.

Kingdom of Scotland

Following the 1266 Treaty of Perth the Hebrides were transferred from Norwegian to Scottish overlordship.[38] At the end of the century, King John Balliol was challenged for the throne by Robert the Bruce. By this point, Somerled's descendants had split into three groups, the MacRory, MacDougalls, and MacDonalds. The MacDougalls backed Balliol, so when he was defeated by de Bruys, the latter exiled the MacDougalls and transferred their island territories to the MacDonalds; by marrying the heir of the MacRorys, the heir of the MacDonalds re-unified most of Somerled's realm, creating the Lordship of the Isles, under nominal Scottish authority. Iona, which had been a MacDougall territory (together with the rest of Lorn), was given to the Campbells, where it remained for half a century.

In 1354, though in exile and without control of his ancestral lands, John, the MacDougall heir, quitclaimed any rights he had over Mull and Iona to the Lord of the Isles (though this had no meaningful effect at the time). When Robert's son, David II, became king, he spent some time in English captivity; following his release, in 1357, he restored MacDougall authority over Lorn. The 1354 quitclaim, which seems to have been an attempt to ensure peace in just such an eventuality, took automatic effect, splitting Mull and Iona from Lorn, and making it subject to the Lordship of the Isles. Iona remained part of the Lordship of the Isles for the next century and a half.

Following the 1491 Raid on Ross, the Lordship of the Isles was dismantled, and Scotland gained full control of Iona for the second time. The monastery and nunnery continued to be active until the Reformation, when buildings were demolished and all but three of the 360 carved crosses destroyed.[39] The Augustine nunnery now only survives as a number of 13th century ruins, including a church and cloister. By the 1760s little more of the nunnery remained standing than at present, though it is the most complete remnant of a medieval nunnery in Scotland.

Post-Union

After a visit in 1773, the English writer Samuel Johnson remarked:

- The island, which was once the metropolis of learning and piety, now has no school for education, nor temple for worship.[40]

He estimated the population of the village at 70 families or perhaps 350 inhabitants.

In the 19th century green-streaked marble was commercially mined in the south-east of Iona; the quarry and machinery survive, see 'Marble Quarry remains' below.[41]

Iona Abbey

Iona Abbey, now an ecumenical church, is of particular historical and religious interest to pilgrims and visitors alike. It is the most elaborate and best-preserved ecclesiastical building surviving from the Middle Ages in the Western Isles of Scotland. Though modest in scale in comparison to medieval abbeys elsewhere in Western Europe, it has a wealth of fine architectural detail, and monuments of many periods. The 8th Duke of Argyll presented the sacred buildings and sites of the island to the Iona Cathedral trust in 1899.[4]

In front of the Abbey stands the 9th century St Martin's Cross, one of the best-preserved Celtic crosses in the British Isles, and a replica of the 8th century St John's Cross (original fragments in the Abbey museum).

The ancient burial ground, called the Rèilig Odhrain (Eng: Oran's "burial place" or "cemetery"), contains the 12th century chapel of St Odhrán (said to be Columba's uncle), restored at the same time as the Abbey itself. It contains a number of medieval grave monuments. The abbey graveyard is said to contain the graves of many early Scottish Kings, as well as Norse kings from Ireland and Norway. Iona became the burial site for the kings of Dál Riata and their successors. Notable burials there include:

- Cináed mac Ailpín, king of the Picts (also known today as "Kenneth I of Scotland")

- Domnall mac Causantín, alternatively "king of the Picts" or "king of Scotland" ("Donald II")

- Máel Coluim mac Domnaill, king of Scotland ("Malcolm I")

- Donnchad mac Crínáin, king of Scotland ("Duncan I")

- Mac Bethad mac Findlaích, king of Scotland ("Macbeth")

- Domnall mac Donnchada, king of Scotland ("Donald III")

- John Smith, Labour Party Leader

In 1549 an inventory of 48 Scottish, 8 Norwegian and 4 Irish kings was recorded. None of these graves are now identifiable (their inscriptions were reported to have worn away at the end of the 17th century). Saint Baithin and Saint Failbhe may also be buried on the island. The Abbey graveyard is also the final resting place of John Smith, the former Labour Party leader, who loved Iona. His grave is marked with an epitaph quoting Alexander Pope: "An honest man's the noblest work of God".[42]

Limited archaeological investigations commissioned by the National Trust for Scotland found some evidence for ancient burials in 2013. The excavations, conducted in the area of Martyrs Bay, revealed burials from the 6th–8th centuries, probably jumbled up and reburied in the 13–15th century.[43]

Other early Christian and medieval monuments have been removed for preservation to the cloister arcade of the Abbey, and the Abbey museum (in the medieval infirmary). The ancient buildings of Iona Abbey are now cared for by Historic Environment Scotland (entrance charge).

Marble quarry remains

The remains of a marble quarrying enterprise can be seen in a small bay on the south-east shore of Iona.[44] The quarry is the source of 'Iona Marble', a beautiful translucent green and white stone, much used in brooches and other jewellery.[45] The stone has been known of for centuries and was credited with healing and other powers. While the quarry had been used in a small way, it was not until around the end of the 18th century when it was opened up on a more industrial scale by the Duke of Argyle.[46] The then difficulties of extracting the hard stone and transporting it meant that the scheme was short lived. Another attempt was started in 1907, this time more successful with considerable quantities of stone extracted and indeed exported, but the First World War put paid to this as well, with little quarrying after 1914 and the operation finally closing in 1919. A painting showing the quarry in operation, The Marble Quarry, Iona (1909) by David Young Cameron, is in the collection of Cartwright Hall art gallery in Bradford.[47] Such is the site's rarity that it has been designated as a Scheduled Ancient Monument.[48]

Present day

The island, other than the land owned by the Iona Cathedral Trust, was purchased from the Duke of Argyll by Hugh Fraser in 1979 and donated to the National Trust for Scotland.[4] In 2001 Iona's population was 125[49] and by the time of the 2011 census this had grown to 177 usual residents.[3] During the same period Scottish island populations as a whole grew by 4% to 103,702.[50]

Iona Community

Not to be confused with the local island community, Iona (Abbey) Community is based within Iona Abbey.

In 1938 George MacLeod founded the Iona Community, an ecumenical Christian community of men and women from different walks of life and different traditions in the Christian church committed to seeking new ways of living the Gospel of Jesus in today's world. This community is a leading force in the present Celtic Christian revival.

The Iona Community runs 3 residential centres on the Isle of Iona and on Mull, where one can live together in community with people of every background from all over the world. Weeks at the centres often follow a programme related to the concerns of the Iona Community.

The 8 tonne Fallen Christ sculpture by Ronald Rae was permanently situated outside the MacLeod Centre in February 2008.[51]

Transport

Visitors can reach Iona by the 10-minute ferry trip across the Sound of Iona from Fionnphort on Mull. The most common route from the mainland is via Oban in Argyll and Bute, where regular ferries connect to Craignure on Mull, from where the scenic road runs 37 miles (60 kilometres) to Fionnphort. Tourist coaches and local bus services meet the ferries.

Car ownership is lightly regulated, with no requirement for an MOT Certificate or payment of Road Tax for cars kept permanently on the island, but vehicular access is restricted to permanent residents and there are few cars. Visitors must leave their car in Fionnphort, but upon landing on Iona they will find the village, the shops, the post office, the cafe, the hotels and the abbey are all within walking distance. Bike hire is available at the pier, and on Mull.

| Preceding station | Ferry | Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terminus | Caledonian MacBrayne Iona Ferry |

Fionnphort |

Accommodation

In addition to the hotels, there are several bed and breakfasts on Iona and various self-catering properties. The Iona Hostel at Lagandorain and the Iona campsite at Cnoc Oran also offer accommodation.

Iona in Scottish painting

The island of Iona has played an important role in Scottish landscape painting, especially during the Twentieth Century. As travel to north and west Scotland became easier from the mid C18 on, artists' visits to the island steadily increased. The Abbey remains in particular became frequently recorded during this early period. Many of the artists are listed and illustrated in the valuable book, Iona Portrayed – The Island through Artists' Eyes 1760–1960,[52] which lists over 170 artists known to have painted on the island.

The C20 however saw the greatest period of influence on landscape painting, in particular through the many paintings of the island produced by F C B Cadell and S J Peploe, two of the ‘Scottish Colourists’. As with many artists, both professional and amateur, they were attracted by the unique quality of light, the white sandy beaches, the aquamarine colours of the sea and the landscape of rich greens and rocky outcrops. While Cadell and Peploe are perhaps best known, many major Scottish painters of the C20 worked on Iona and visited many times – for example George Houston, D Y Cameron, James Shearer, John Duncan and John Maclauchlan Milne, among many.

Media and the arts

Samuel Johnson wrote "That man is little to be envied whose patriotism would not gain force upon the plains of Marathon, or whose piety would not grow warmer amid the ruins of Iona."[53]

In Jules Verne's novel The Green Ray, the heroes visit Iona in chapters 13 to 16. The inspiration is romantic, the ruins of the island are conducive to daydreaming. The young heroine, Helena Campbell, argues that Scotland in general and Iona in particular are the scene of the appearance of goblins and other familiar demons.

In Jean Raspail's novel The Fisherman's Ring (1995), his cardinal is one of the last to support the antipope Benedict XIII and his successors.

In the novel The Carved Stone (by Guillaume Prévost), the young Samuel Faulkner is projected in time as he searches for his father and lands on Iona in the year 800, then threatened by the Vikings.

"Peace of Iona" is a song written by Mike Scott that appears on the studio album Universal Hall and on the live recording Karma to Burn by The Waterboys. Iona is the setting for the song "Oran" on the 1997 Steve McDonald album Stone of Destiny.

Kenneth C. Steven published an anthology of poetry entitled Iona: Poems in 2000 inspired by his association with the island and the surrounding area.

Iona is featured prominently in the first episode ("By the Skin of Our Teeth") of the celebrated arts series Civilisation: A Personal View by Kenneth Clark (1969).

Iona is the setting of Jeanne M. Dams' Dorothy Martin mystery Holy Terror of the Hebrides (1998).

The Academy Award–nominated Irish animated film The Secret of Kells is about the creation of the Book of Kells. One of the characters, Brother Aiden, is a master illuminator from Iona Abbey who had helped to illustrate the Book, but had to escape the island with it during a Viking invasion.

After his death in 2011, the cremated remains of songwriter/recording artist Gerry Rafferty were scattered on Iona.[54]

Frances Macdonald the contemporary Scottish artist based in Crinian, Argyll, regularly paints landscapes on Iona.

Iona Abbey is mentioned in Tori Amos's "Twinkle" from her 1996 album Boys for Pele: "And last time I knew, she worked at an abbey in Iona. She said 'I killed a man, T, I've gotta stay hidden in this abbey' "

Iona is the name of a progressive Celtic rock band (first album released in 1990; not active at present), many of whose songs are inspired by the island of Iona and Columba's life.

Neil Gaiman's poem "In Relig Odhrain", published in Trigger Warning: Short Fictions and Disturbances (2015), retells the story of Oran's death, and the creation of the chapel on Iona. This poem was made into a short stop-motion animated film, released in 2019.[55]

Gallery

The Isle of Mull, showing the location of Iona

The Isle of Mull, showing the location of Iona St Martin's Cross (from the 9th century)

St Martin's Cross (from the 9th century)

Iona, showing the location of the Abbey and Dùn Ì

Iona, showing the location of the Abbey and Dùn Ì Abbey cloisters

Abbey cloisters Looking towards St. Columba's Bay

Looking towards St. Columba's Bay Iona Book Shop

Iona Book Shop Jetty at Baile Mòr

Jetty at Baile Mòr

Footnotes

- The name of the Gaulish god Ivavos is of similar origin, associated with the healing-well of Evaux in France.

- For etymology of Ì and Latinised derivative Iona, see Watson (2004), pp. 87–90.

- The record is tentative, the press cutting the record refers to identifying "'Sheep Island', one of the Torran Rocks near Iona" but there is no other obvious contender.

References

Sources

- Christian, J & Stiller, C (2000), Iona Portrayed – The Island through Artists' Eyes 1760–1960, The New Iona Press, Inverness, 96pp, numerous illustrations in B&W and colour, with list of artists.

- Dwelly, Edward (1911). Faclair Gàidhlig gu Beurla le Dealbhan/The Illustrated [Scottish] Gaelic- English Dictionary. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-874744-04-1.

- Fraser, James E. (2009). From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. 1. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1232-1.

- Gregory, Donald (1881) The History of the Western Highlands and Isles of Scotland 1493–1625. Edinburgh. Birlinn. 2008 reprint – originally published by Thomas D. Morrison. ISBN 1-904607-57-8.

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Hunter, James (2000). Last of the Free: A History of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Edinburgh. Mainstream. ISBN 1-84018-376-4

- Johnson, Samuel (1775). A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland. London: Chapman & Dodd. (1924 edition).

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003). "Placenames" (PDF). Edinburgh: Scottish Parliament. p. 67. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- Marsden, John (1995). The Illustrated Life of Columba. Edinburgh. Floris Books. ISBN 0-86315-211-2.

- Murray, W. H. (1966). The Hebrides. London. Heinemann.

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh (1998) Vikings in Ireland and Scotland in the Ninth Century CELT.

- Watson, W. J., The History of the Celtic Place-names of Scotland. Reprinted with an introduction by Simon Taylor, Birlinn, Edinburgh, 2004. ISBN 1-84158-323-5.

- Woolf, Alex (2007), From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070, The New Edinburgh History of Scotland, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-7486-1234-5

Citations

- "Map of Scotland in Scots - Guide and gazetteer" (PDF).

- Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 80–84

- Ordnance Survey. OS Maps Online (Map). 1:25,000. Leisure.

- Anderson, Joseph (Ed.) (1893) Orkneyinga Saga. Translated by Jón A. Hjaltalin & Gilbert Goudie. Edinburgh. James Thin and Mercat Press (1990 reprint). ISBN 0-901824-25-9

- Murray (1966) p 81

- The perfect way to go island hopping in the Hebrides

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. xiii

- Watson, Celtic Place-Names, pp. 87–90

- Watson, Celtic Place-Names, pp. 87–88.

- Watson, Celtic Place-Names, pp. 88–89

- Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 67.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 80.

- "eDIL – Irish Language Dictionary". dil.ie. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Dwelly (1911)

- Watson, Celtic Place-Names, p. 88

- Broderick, George (2013). "Some island names in the former 'Kingdom of the Isles': a reappraisal" (PDF). Journal of Scottish Name Studies. 7: 1–28: 13, fn.30.

- Fraser (2009) p. 71.

- original (translation)

- Watson, Celtic Place-Names, p. 88, n. 2

- Murray (1966) p. 81.

- "Onshore Geoindex". British Geological Survey. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Ross of Mull, Scotland sheet 43S, Solid and Drift Edition". BGS large map images. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Scotland Census 2001 – analyser

- Murray (1966) pp. 82–83.

- "It's Been Emotional" Archived 29 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine ionabeachparty.co.uk. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "Cathcart Park: Soa Island, Passage Of Tiree" RCAHMS. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- John Bartholomew: Modern Hy (1874)

- Admonan The Life of St. Columba, Founder of Hy ed. William Reeves (1857) University Press for the Irish Archaeological and Celtic Society. pp. 248–50.

- Koch, pp. 657–658.

- Forte, Angelo; Oram, Richard; Pedersen, Frederik (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 55–58. ISBN 9780521829922.

- Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2012). Pages from the Book of Kells. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00AN4JVI0

- "BBC – History – Scottish History". BBC. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Ó Corráin (1998) p. 11

- Gregory (1881) pp. 4–6

- Woolf (2007) pp. 217–18

- Hunter (2000) pp. 110–111

- "Isle of Iona Visitor Guide, Hotels, Cottages, Things to Do in Scotland". scotland.org.uk. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland, Project Gutenberg.

- Industrial Archaeology review, Vol I Number 1 Autumn 1976 The Marble Quarry, Iona, Inner Hebrides, D. J. Viner. Oxford University Press

- Walk Of The Month: The island of Iona Archived 22 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine The Independent 4 June 2006

- Alistair, Munro (17 May 2013). "Isle of Iona may be ancient burial site". The Scotsman. Edinburgh, Scotland. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- "Iona Marble Quarry from the Gazetteer for Scotland".

- "About Iona Marble".

- MacArthur, E Mairi, Iona, Colin Baxter Island Guide (1997) Colin Baxter Photography, Grantown-on-Spey, see Chapter 10, 128pp.

- "The Marble Quarry, Iona". ArtUK. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Iona Marble Quarry, quarry NE of An t-Aird (SM5255)". Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- "Scotland's 2011 census: Island living on the rise". BBC News. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "The Fallen Christ on Iona". iona.org.uk. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- Christian, Jessica & Stiller, Charles (2000), Iona Portrayed – The Island through Artists' Eyes 1760–1960, The New Iona Press, Inverness, 96pp, numerous illustrations in B&W and colour, with list of artists.

- Johnson (1775) p. 217

- "Gerry Rafferty went to meet his maker sober and unafraid, curious and brave". The Scotsman. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- "The Grave of St Oran". Retrieved 21 June 2020.

Further reading

- Campbell, George F. (2006). The First and Lost Iona. Glasgow: Candlemas Hill Publishing. ISBN 1-873586-13-2 (and on Kindle).

- MacArthur, E Mairi, Iona, Colin Baxter Island Guide (1997) Colin Baxter Photography, Grantown-on-Spey, 128pp.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iona. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Iona. |

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article "Iona". |

- Visit Mull & Iona (Official tourism website for the Isles of Mull and Iona)

- Isle of Iona, Scotland (A visitors guide to the Isle)

- The Iona Community

- Computer-generated virtual panorama Summit of Iona Index

- Map sources for Iona

- Photo Gallery of Iona by Enrico Martino

- National Trust for Scotland property page