St James' Church, Sydney

St James' Church, commonly known as St James', King Street, is an Australian heritage-listed Anglican parish church located at 173 King Street, in the Sydney central business district of the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales. Consecrated in February 1824 and named in honour of St James the Great, it became a parish church in 1835. Designed in the style of a Georgian town church by the transported convict architect Francis Greenway during the governorship of Lachlan Macquarie, St James' is part of the historical precinct of Macquarie Street which includes other early colonial era buildings such as the World Heritage listed Hyde Park Barracks.

| St James' Church, Sydney | |

|---|---|

| St James, King Street | |

St James' Church in about 1890, by Henry King | |

St James' Church, Sydney Location in the Sydney central business district | |

| 33°52′10″S 151°12′40″E | |

| Location | 173 King Street, Sydney central business district, City of Sydney, New South Wales |

| Country | Australia |

| Denomination | Anglican Church of Australia |

| Churchmanship | Anglo-Catholic |

| Website | sjks |

| History | |

| Status | Parish church |

| Founder(s) | Governor Macquarie |

| Dedication | St James |

| Consecrated | 11 February 1824 by Samuel Marsden |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | |

| Style | Georgian |

| Groundbreaking | 7 October 1819 |

| Administration | |

| Parish | St James', King Street |

| Diocese | Sydney |

| Clergy | |

| Rector | Andrew Sempell |

| Assistant | John Stewart |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Warren Trevelyan Jones |

| Organist(s) | Alistair Nelson |

| Official name | St. James' Anglican Church; St James' Church |

| Type | State heritage (built) |

| Criteria | a., b., c., d., e., f. |

| Designated | 3 September 2004[1] |

| Reference no. | 1703 |

| Type | Church |

| Category | Religion |

| Builders | Convict labour |

The church remains historically, socially and architecturally significant. The building is the oldest one extant in Sydney's inner city region. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 3 September 2004;[1] and was listed on the (now defunct) Register of the National Estate, and has been described as one of the world's 80 greatest man-made treasures.

The church has maintained its special role in the city's religious, civic and musical life as well as its close associations with the city's legal and medical professions through its proximity to the law courts and Sydney Hospital. Its original ministry was to the convict population of Sydney and it has continued to serve the city's poor and needy in succeeding centuries.

Worship at St James' is in a style commonly found in the High Church and moderate Anglo-Catholic traditions of Anglicanism. It maintains the traditions of Anglican church music, with a robed choir singing psalms, anthems and responses in contrast to the great majority of churches in the Anglican Diocese of Sydney where services are generally celebrated in styles associated with Low Church and Evangelical Christian practices. The teaching at St James' has a more liberal perspective than most churches in the diocese on issues of gender and the ordination of women.

Location

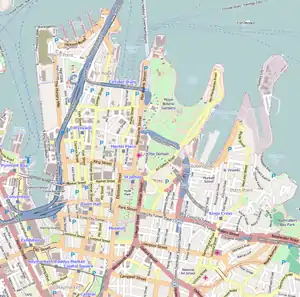

St James' Church is located at 173 King Street, Sydney, in the legal and commercial district, near Hyde Park and adjoining Queen's Square, adjacent to the Greenway Wing of the Supreme Court of New South Wales.[2] The church forms part of a group of notable colonial buildings along Macquarie Street, which runs from Queen's Square to Sydney Harbour. At the time of construction, the church and the buildings nearby were "Sydney's most distinguished structures ... on the highest ground, and, socially speaking, in the best part of the city".[3]

The geographical parish of St James' is one of the 57 parishes of Cumberland County, New South Wales, and it initially shared responsibility for an area that extended as far as Sydney Heads. St James' acquired its own parish in 1835.[4][5][6] Its boundaries have since remained essentially unchanged.[7]

The underground St James railway station is named after the church. The precinct around the church is informally known as St James'.[5][8][9]

History

Foundation and consecration

The building of St James' Church was commissioned by Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1819, designed by the convict architect Francis Greenway and constructed between 1820 and 1824 using convict labour.[1] Governor Macquarie and Commissioner John Bigge laid the foundation stone on 7 October 1819.[10][11] The building was originally intended to serve as a courthouse[12] as Macquarie had plans for a large cathedral to be built on the present location of St Andrew's Cathedral but they were put on hold by the intervention of Bigge who had been appointed to conduct a Royal Commission into the colonial government.[11][13] Bigge initially approved of the courthouse project but by February 1820, less than four months after his arrival, he strongly recommended its conversion into a church.

"The reason for Bigge's change of mind may be found in the appointment, three years later, of his brother-in-law [and secretary], Mr TH Scott, a wine merchant, as Archdeacon".[14] The design of the courthouse was modified before construction with the addition of a steeple at the western end, to serve as a church, while the adjacent school buildings were put into use as a courthouse.[10] The first service was held in the unfinished church on the Day of Epiphany, 6 January 1822, the text being from Isaiah, Chapter 60: "Arise! Shine, for thy light has come. The glory of the Lord has risen upon thee". It was anticipated in the Sydney Gazette's report of the event that the church, when fitted out with stalls and galleries, would hold 2,000 people.[11] The church was consecrated by the senior chaplain, Samuel Marsden, on 11 February 1824.[10][1]

First years: 1824–38

Before the building of St James', Sydney's growing population had been served by St Philip's Church, York Street. However, as St James' was able to hold more people than St Philip's and clergy meetings as well as ordinations were held there, it quickly became the centre of official church activity.[15]

There was both official and general concern about the lack of morality within the predominantly male population, and the establishment of churches and of education was seen as a method of combatting this. The 19th-century church historian, Edward Symonds, credited a "better moral and spiritual tone" in the colony to "decent churches" and "the advent of additional clergy, headed by William Cowper, in 1808".[16][17] The first rector of St James', Richard Hill, was ordained specifically for colonial ministry and sent from London as assistant to William Cowper at St Philip's.[18] Hill was energetic and a good organiser, with progressive views on education. He instigated a number of projects to aid the community, including an infants' school in the crypt of the church and a Sunday School.[19]

The focus of the church's liturgy at the time was on preaching and the church's interior reflected this. The east end of the church had a triple-decker pulpit placed centrally, from which the service was led and the sermon preached. From this pulpit Broughton, Pattison, Selwyn, Barker and Barry preached.[20] The parish clerk led the congregation in the responses from its lower level.[19] Between the three windows which at that time occupied the eastern wall, there were two large panels displaying the words of the Lord's Prayer, the Apostles' Creed and the Ten Commandments.[21] The church was full of box pews which faced each other across a central aisle. The western end had a gallery, which is still in place, for the convicts. Pews were rented to provide a source of income for the church and the whole was arranged in "rigid social order" with the poor occupying the free seats.[16][19] Sunday services consisted of Morning and Evening Prayer, with Holy Communion taking place only occasionally as an addition to the regular service. For this reason, there was no visual emphasis on the communion table, which was a small portable one, and no reredos.[19]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

St James' suffered from a major scandal in the late 1820s ("a period of personal quarrels and violent newspaper controversies")[22] when Commissioner Bigge's secretary and brother-in-law, Thomas Hobbes Scott, who had been made Archdeacon of New South Wales in 1825, came into conflict with a parishioner, Edward Smith Hall.[11] Archdeacon Scott ordered that Hall should vacate the pew he rented at St James' for himself and his six daughters.[11] As Hall continued to occupy the pew, constables attended Sunday services to prevent his occupation of the pew by boarding it up and making it secure with iron bands.[22] Hall, critical of both the archdeacon and Governor Ralph Darling, was also a partner with Arthur Hill in the ownership of newspaper The Monitor. He published an attack on the archdeacon, for which he was sued for libel. The courts fined him only £1 and placed him on a bond. Hall appealed to Reginald Heber, Bishop of Calcutta (who was the relevant ecclesiastical authority at the time)[20][23] and to the law where he was awarded £25 damages.[24] The archdeacon, who was extremely unpopular, returned to London in 1828.[11]

The first major alteration to the church was the enclosing of the south portico to form a vestry. In 1832 John Verge constructed another vestry at the eastern end of the church, in strict conformity with the architectural style of Greenway.[25] Growth of the congregation necessitated further changes. Galleries were added along the northern and eastern walls. As the three eastern windows had been blocked by Verge's vestry, the interior became increasingly badly lit with every change. Verge's solution was to pierce ocular windows high in the walls to light the galleries.[25]

In 1836, Richard Hill had a fit of apoplexy in the vestry and died.[18] Soon after this dramatic event, and while the church was still in mourning, William Grant Broughton was installed as Bishop of Australia during a service in St James' lasting five hours.[26][27] Since Macquarie's plans for a new cathedral on George Street had not come to fruition, Broughton acted as if St James' were a pro-cathedral.[28] Robert Cartwright and then Napoleon Woodd succeeded Richard Hill at St James'.[26][29]

Ministry of Robert Allwood: 1840–84

.jpg.webp)

In 1839, Robert Allwood, educated at Eton College and the University of Cambridge, arrived in Sydney[15][30] and was appointed to St James' by William Broughton,[15] in which parish he served for 44 years until his retirement in 1884. Allwood was an important patron of education in Victorian Sydney. Under him, the parish school expanded and his teacher training college became a "model school".[30] He was also the principal tutor at St James' College, which originally met in St James' parsonage (on the corner of King Street and Macquarie Street) until it was transferred to Lyndhurst at The Glebe.[31]

In 1848, St James' was the venue for a full military funeral, "attended by 150 carriages"[32] and in 1878 Allwood officiated at the wedding of Nora Robinson and Alexander Kirkman Finlay.[33] As the second vice-regal wedding in the colony this ceremony was attended by many dignitaries and attracted a "crushing" crowd of 10,000 cheering onlookers.[34][35] Edmund Barton, the first Prime Minister of Australia, was baptised at St James' on 4 July 1849.[36]

Unlike Hill, Allwood advocated the principles of the Oxford Movement (also known as "Tractarianism" after its publication of Tracts for the Times), which stressed the historical continuity of the Church of England, and placed a high importance upon the sacraments and the liturgy.[30][37] "The culmination" of a trend towards Tractarianism in the colony was the founding in 1845, of St James' College – "the first seminary for training local ordinands".[38] However, many colonial Anglicans were unhappy with Tractarian trends because Roman Catholics "were equated with Irish",[38] and with "Romanism". "Serious differences opinion in matters of doctrine" began to "escalate into public debate as the influences of the Oxford Movement began to be felt in the Australian colonies" in the 1840s.[39]

Allwood's sermons were brief and Holy Communion was celebrated every Sunday. The organ, which had been installed in 1827, was moved to the space of the southern vestry, and the pulpit and reading desk place in front of it where they could be seen from all parts of the church. The holy table continued to be located at the eastern end of the building.[37] Broughton supported the Tractarian views of Allwood, but his successor, Frederic Barker, who became bishop in 1855, was strongly Evangelical.[40] The division in style between St James' and the "low church" ethos that predominated in the Sydney Diocese began at this time.[37]

Changes: 1884–1904

During the 1880s Sydney became a prosperous city, commerce and industry flourished, and the suburbs expanded. As more churches were built and fewer people lived in the heart of the city, the congregation of St James' Church shrank. The challenge that it faced was to minister effectively to city workers, rather than dwellers, to serve the poor of the city, and to attract those whose preference was for the style of worship and intellectual, topical preaching that distinguished St James' from many of the newly created parish churches.[41] The young Henry Latimer Jackson, from Cambridge, was appointed in 1885. He introduced weekday services and a magazine called The Kalendar, one of Australia's first parish papers.[42] He also lectured at Sydney University, addressed conferences, spoke at synod and acted as secretary to the newly established Sydney Church of England Boys' Grammar School.[43] However, his sermons were described as "not so much opposed, as simply not understood".[44] He resigned in 1895 after accepting a position in the Diocese of Ely.[45]

Although Sydney was prospering, St James' had an acute shortage of money and "the government considered resuming the site for a city railway".[44][46] The trustees at this time leased the parsonage and, in 1894, used the money for urgent restoration to the exterior of the building. The architect Varney Parkes replaced the old spire, using copper that was pre-weathered so that there was no radical change in its appearance.[47] He removed infilling from the north portico and designed a new portico and entrance to the tower to match that of the eastern vestry. The result was to make the north face of the building its most significant aspect.[46]

Jackson's successor was William Carr Smith, a man with socialist ideals and a commitment to social reform and spiritual outreach.[48] He preached long and engaging sermons inside the church and for a time in the open air in The Domain as well.[49] Carr Smith had brought with him from England the "most recent developments" in the restoration of ancient liturgy, so he was able to help St James' play a "notable part" in Sydney's revival of Anglo-Catholicism, setting "new standards of ceremonial".[50] To serve these purposes the architect John H. Buckeridge was employed to transform the building's interior, completing the work in 1901.[48] The most significant change was the new emphasis given to the altar, which was made the focus of attention and "flanked by the pulpit, reading desks and lectern."[51] The "principal features" under the Carr Smith plan were the construction of the apse, set into the eastern vestry to create a sanctuary; the raising of the chancel floor which created a platform, five steps above the nave for the choir, framed by the organ divided into two sections; the making of a new, unobtrusive entrance to the tower and western gallery; and the removal of the box pews and the eastern and northern galleries.[52] The memorial plaques were also rearranged. The choir was ornamented with a mosaic floor and ornate brasswork which complemented the large brass eagle lectern by the English ecclesiastical suppliers, J. Wippell and Company, that commemorated Canon Robert Allwood.[41][48] The floor of the pulpit was made from parts of the old three-decker one.[20][53] The organ, refurbished and enlarged by Davidson of Sydney, was installed in 1903.[48] With the removal of the organ, the south vestry was made into a side chapel. Eight large stained glass windows were installed between 1903 and 1913, along with a new pulpit, altar and retable, all of which were given as memorials.[54] Another improvement was "the placing of double windows on the King-street side to shut out the sound of the traffic, which hitherto has been a serious annoyance to both the officiating clergymen and the congregation".[55] In 1897, St James' Hall was offered to Dorotheos Bakalliarios, a Greek Orthodox priest from Samos for Orthodox services in Sydney.[56] In 1904 the diocesan architect, John Burcham Clamp, was employed to design a new parish hall.[48]

20th century

In 1900, the Governor, Earl Beauchamp, presented to the church a number of embroidered stoles made by the Warham Guild of London, along with copes and chasubles.[57] The centenary of the laying of the foundation stone was celebrated in October 1919 with a program of events that extended over nine days. Festivities included services at which the Bishops of Armidale and Bathurst were special preachers, music, processions, a lantern lecture on "Old Sydney" by the municipal librarian, and social events such as a ferry outing and a luncheon at which the chief guest was the Governor Sir Walter Davidson accompanied by his wife Lady Davidson.[53] Also scheduled was a welcome to soldiers returned from the Great War.[11][58] An illustrated historical memoir was produced and sold for two shillings.[59]

The celebrations for the centenary of the Oxford Movement occurred during the tenure of the eighth rector of St James', Philip Micklem.[60] However, "they were not centred on the cathedral, but on St James'", Sydney being the only Australian diocese that "failed officially to observe the occasion".[61] Micklem chaired a rally on 19 July 1933 in St James' Hall that was attended by governor Philip Game and Lady Game, "and five bishops representing three states."[62] The 180th anniversary of the Oxford Movement fell in the 21st century, and the rector of St James' preached at the commemoration.[63]

Micklem was "a pioneer advocate of the preservation of early colonial architecture".[64] As the century progressed, there were a number of threats to the church's historic environment, which includes Greenway's Law Courts and Hyde Park Barracks.[65][66][67] In spite of the threats to these colonial era buildings, they survived to form an important Sydney precinct.[68] Both the building and the organisation continued to serve the city. During World War II, for example, the crypt was used as a "Hostel for Soldiers, Sailors and Airmen"[69] and the ninth rector, Edwin John Davidson, incumbent during that period, "gained fame" for the church with his "pungent sermons on current affairs".[70] The eleventh rector, Frank Cuttriss, had an ecumenical outlook – he was a member of a meeting of the World Council of Churches at Uppsala and an observer to the Second Vatican Council.[71]

St James' was the locus of many notable events throughout the 20th century, including weddings and funerals of famous, significant or notorious people, visits from theologians and senior clerics, and when needed, services for the Lutheran communities.[72] At the wedding of singer Gladys Moncrieff and Tom Moore on 20 May 1924, the crowd in the streets nearby was so large that traffic was brought to a standstill, several women fell and two were so badly hurt they were taken to hospital.[73] At the time Moncrieff was appearing in The Merry Widow and returned to the stage on the night of her wedding.[74][75] St James' was represented in the opening ceremonies of the Sydney Harbour Bridge by a float in the form of the church building.[76] The church was "packed to the doors" when the seventh rector, W.F. Wentworth-Sheilds, officiated at the "impressive funeral" of Walter Liberty Vernon in 1914.[77] In 1950, four thousand people were reported to have lined the streets after the State funeral at St. James' of the first Minister for Sweden in Australia, Constans Lundquist, who died suddenly at the Swedish Legation in Sydney.[78][79][80][81] Controversial former Governor-General, Sir John Kerr had a private funeral and memorial service in St James' in 1991 rather than a State funeral because of his fall from favour as the result of his decision to sack the Whitlam government in 1975.[82][83] Delivering the sermon at St James' during an ecumenical event on 14 October 1993, Desmond Tutu thanked Australians for supporting the struggle against apartheid.[84]

During the 20th century both choral and organ musical components developed to a high standard and were integral to the liturgy at St James'.[85] In addition, music was offered to the wider community in the form of recitals, often in ways that elucidate the liturgy and take advantage of church acoustics and sacred settings. Weekday recitals, such as the organ recitals given in 1936 of music by Bach,[86] continued in addition to the music played on Sundays.

21st century

In the 21st century, St James' continues its work in the city centre via its ministry and engagement in the issues of the day. In the 19th century, there were controversies about tractarianism; in the 20th, there was the impact of the two world wars; in the 21st century, the church has confronted the difficult and topical issues of violence, euthanasia,[87] refugees,[88][89] marriage and sexuality.[90] The church's relationship with government and the legal community began when the colony was under military government and the Church of England was the established church. Due to the church's history and its proximity to the convict barracks (later an immigration centre), the law courts (both the old and the new ones) as well as the New South Wales parliament, the relationship continues. It is evident in special services attended by the governor as well as the annual service to mark the opening of the law term.[91]

St James' commitment to social justice and education began in the 19th century with efforts to serve both convicts and settlers. It continued in the 20th with support for people affected by war, for example, when the church became "a busy centre of war-time life".[92] Since early in the 20th century, service to the community has included visits to those imprisoned or ill as well as practical help to the city's homeless[93][94][95] and an annual schedule of educational seminars at the St James' Institute.[96]

On 6 February 2012, the rector Andrew Sempell officiated at a thanksgiving for Queen Elizabeth II to mark the sixtieth anniversary of her accession to the throne in a service attended by the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, George Pell and the Governor of New South Wales, Marie Bashir and on 9 September 2015, when Queen Elizabeth II became the longest-serving British monarch and Queen of Australia, there was a special Choral Evensong service to give thanks.[97][98] At the Jubilee service, the Chief Justice of New South Wales, Tom Bathurst, read the first lesson and the service concluded with the Australian National Anthem and an organ postlude of Edward Elgar's Pomp and Circumstance March No. 4.[97] On 23 March 2012, a memorial service for Margaret Whitlam, wife of former Prime Minister of Australia, Gough Whitlam, was attended by Prime Minister Julia Gillard, and several former prime ministers.[99]

Description

Architecture

One of Greenway's finest works, St James' is listed on the (now defunct) Register of the National Estate.[100][101][102][103] It has been called an "architectural gem"[104] and was featured by Dan Cruickshank in the BBC television series Around the World in 80 Treasures.[105] From 1966 to 1993 the spire of St James' appeared on the Australian Australian ten-dollar note among other Greenway buildings.[106][107] In 1973, the church appeared on a 50 cent postage stamp, one of four in a series illustrating Australian architecture issued to commemorate the opening of the Sydney Opera House.[108] The Old Supreme Court building, also designed by Greenway with alternations by others, located next to the church is of the same date.[109] Across the square is Greenway's "masterpiece", the UNESCO World Heritage listed-Hyde Park Barracks, designed to align with the church.[110] Beside the barracks stands Sydney's oldest public building, part of the General Hospital built in 1811 and now known as the Mint Building. Separated from the Mint by the present-day Sydney Hospital is Parliament House, Sydney, of which the central section is a further part of the early hospital, and is now home to the New South Wales State Parliament.[111] In the mid-twentieth century St. James' was one of several historic buildings in the precinct that were threatened with demolition.[112]

The church was constructed between 1820 and 1824 with later additions made in 1834 by John Verge who designed the vestries at the eastern end.[113] Apart from these vestries, which retain the established style and proportions, the church externally remains "fine Georgian"[114] much as Greenway conceived it.[51][115] Relying on the "virtues of simplicity and proportion to achieve his end",[116] Greenway maintained the classical tradition, unaffected by the Revivalist styles that were being promoted in London at the time he arrived in the colony.[117] He planned the church to align with his earlier Hyde Park Barracks, constructed in 1817–19. The two buildings have similar proportions, pilasters and gables and together constitute an important example of town-planning.[101] Before the advent of high-rise buildings, the 46-metre (150 ft) spire used to "serve as a guide for mariners coming up Port Jackson".[4]

St James' originally took the form of a simple rectangular block, without transepts or chancel, with a tower at the western end and a classical portico of the Doric order on either side. To this has been added Verge's vestry framed by two small porticos, and a similar portico as an entrance to the tower. The church is built of local brick, its walls divided by brick pilasters into a series of bays. The walls are pierced by large windows with round arched heads in a colour that separates and defines them against the walls. The roof carries over the end walls with the gable forming triangular pediments of classical proportions carrying a cornice across the eaves line. Thus the architectural treatment on the side walls is continued around the end walls.[113]

Interior

The original interior differed greatly in layout from that of the present. There was no structural chancel, the focus of the church being a large pulpit. During the mid 19th century galleries overlooked the pulpit from three sides.[46] Of the original galleries, only the western one of Australian Red Cedar remains in place. The coffered ceiling (an addition from 1882 replacing the original lath and plaster ceiling), the low-backed pews (from shortly after) and the predominantly classical memorials all contribute to the present interior retaining the character of a Georgian church.[1]

At the eastern end, the communion table is set into a small apse with its semi-dome adorned with gold mosaic tiles that were added in 1960.[118] The altar is a commemorative gift from the Lloyd family, whose son was the first server appointed at St James'.[118] It generally has an altar frontal in the colour of the liturgical season or festival. With no structural choir area, the chancel is built out and into the body of the church as a platform enclosed within gated wrought iron and brass railings and approached by steps. The mosaic floor of the chancel is ornately with designs showing the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit (Wisdom, Understanding, Counsel, Ghostly Strength, Knowledge, Godliness and Holy Fear) along with symbols of St James the Great (the staff, scrip, palm, scallop shell and hat of the pilgrim).[118] The chancel is framed on either side by the organ pipes.[119]

There are five large stained glass windows on the northern and southern walls and additional windows in the stairwell to the belltower and on the western wall. Most of them are designed by Percy Bacon Brothers and the majority were donated as memorials by parishioners in the period from 1900 to 1910. The stained glass fanlight depicting James and John, the sons of Zebedee, was designed by Australian artist Norman Carter in 1930.[120][121] The window behind the baptismal font, depicting Christ with the Children, was repaired and rededicated in 2004 by the fifteenth rector in the presence of the then Primate, Peter Carnley.[122]

Chapel of the Holy Spirit

Previously enclosed and used as a vestry and then an organ chamber, the south porch became a chapel in 1903. In 1988, the side chapel was remodelled and dedicated as the Chapel of the Holy Spirit.[123] The parish and the Bicentennial Council of New South Wales funded the redesign which saw the removal of the infilling from between the columns of the portico and its replacement with stained glass. The award-winning "Creation Window", designed by Australian artist David Wright,[124][125] spreads across the three walls and represents the interaction of earth, air, fire and water, symbolic of the action of the Spirit in creation, in life and in rebirth in Christ.[126] The new furniture for the chapel was designed by Leon Sadubin.[127]

Crypt and Children's Chapel

Beneath the church is a large undercroft, built of brick and groin vaulted. It has been used for many purposes: as a residence by the widow of Richard Hill and later by a verger; by Canon Allwood as a part-time bedroom; for the parish's schools; and as a shelter by Australian, American and British armed forces during the two world wars.[4] Rector Francis Wentworth-Sheilds gave the city parish "a big role as a drop-in centre for servicemen" during the First World War.[128] During the Second World War bed and bedding were provided to over 30,000 Allied servicemen.[129]

The western bay on the south side of the crypt is the Chapel of St Mary and the Angels, better known simply as the "Children's Chapel". It was opened in 1929 as a chapel for younger children. A specially adapted form of Eucharist is celebrated there on the first Sunday of the month. All four walls of the chapel and its ceiling are decorated with murals designed by the writer and artist Ethel Anderson and executed by the Turramurra Wall Painters Union, a group of Modernist painters she founded in 1927.[130] The murals underwent extensive conservation in 1992–1993.[131]

The crypt was restored by Geoffrey Danks in 1977–78.[132] In the 21st century, the bays on either side of the crypt's central corridor are used for a variety of purposes. At the eastern end they house a commercial kitchen. Some bays are used as offices; one (The Chapel of All Souls) contains a columbarium; another houses a lending library for parishioners.[57]

Memorials, monuments, records

St James' provides a record of important elements of Sydney's history in both physical and documentary form.[134] There are over 300 memorials commemorating important members of 19th century colonial society, people who served the colony generally and parishioners from the 20th century. In addition, many of the stained glass windows and items of furniture have been donated as memorials. For example, the large stained glass window of Saint George on the northern wall is a memorial to Keith Kinnaird Mackellar, who died in the Second Boer War aged 20.[135] He was the brother of poet Dorothea Mackellar. These memorials are the reason the church was sometimes called "The Westminster Abbey of the South".[15] As early as 1876, the wall tablets were described as "full of sad memories to the old inhabitants, interesting reminiscences to those who have studied Australian history".[136]

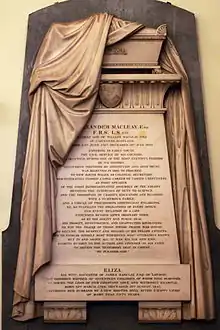

The first monument erected in the church was the memorial to Commodore Sir James Brisbane, who died in Sydney on his way to serve in South America in command of HMS Warspite. It was sculpted by Sir Francis Chantrey, sent to Sydney by Lady Brisbane and installed in the church in 1830. The Brisbane memorial began the tradition of memorial tablets to "prominent people".[137] The memorial to Robert Wardell in 1834 rendered "bushranger" into Latin as "a latrone vagante occiso".[4] Four other monuments were installed between 1830 and 1839. The only memorial on which an indigenous Australian appears is that of Edmund Kennedy[138] (said to have been "a communicant at St James’")[139] on whose tablet Jackey Jackey is remembered.[20][139] There are memorials to the Macleay family of naturalists, Alexander and William Sharp Macleay.

The largest single memorial of the 20th century is the war memorial, to the design of Hardy Wilson, dedicated on 14 June 1922. It commemorates more than 50 men associated with St James' who were killed in the First World War, throughout which the roll of honour was regularly read during the Eucharist.[140] In 2014, St James' was part of a series of commemorations of the bicentenary of the death of the colony's first Governor, Arthur Phillip. On 31 August, a memorial plaque, similar in form to one placed in the nave of Westminster Abbey on 9 July,[141][142] was unveiled by the 37th Governor, Marie Bashir.[143]

The church has all its baptismal and marriage registers dating from 1824 to the present day. These were originally handwritten; printed forms came into existence "by government order" in 1826.[144] Since it was not compulsory to register births, deaths and marriages until after 1855,[145] the records held by St James' are particularly valuable to historians and genealogists and copies are held in the National Library of Australia.[146]

Renovation, restoration, conservation

Since its erection, the building has undergone significant repair, renovation and conservation, including work on the building fabric, the stained glass windows, the mosaic floors in the chancel and sanctuary and conservation of the Children's Chapel. Major work was done on the interior and the spire in the 1890s[4] and on the crypt in the 1970s.[132]

The spire was extensively restored from 2008 to 2010, including the tower masonry, the interior framing, the copper covering and the orb and cross.[147] The spire was rededicated on 20 October 2010.[148] The restorations were awarded the National Trust of Australia Built Heritage Award on 4 April 2011[149] and the AIA Greenway Award for Heritage.[150][151] The jury said that the restoration work showed "consummate care by the architect, the engineer and the builder in conserving the original structure and fabric of the building, improving its strength, performance and waterproofing".[152]

Restoration continued with work on the church's slate roof and sandstone perimeter fence. The Spanish slates, installed in the 1970s, proved not to be durable in Sydney's climate due to their high iron content and their poor fixing had resulted in further damage. The solution to the deterioration was to replace the slates using Welsh slates. The roof project was completed after a fund-raising effort supported by the National Trust of Australia. In 2013, the interior was repainted after preparation that involved "colour testing and selection, memorial protection and ceiling acoustic repairs".[153] As a heritage-listed building, the church has a program of continual conservation. Its custodians remain "ever mindful" of their responsibility to the wider public as well as to the congregation.[104]

Worship and ministry

Liturgy

St James' offers three Eucharists on Sundays: a Said Eucharist, a Sung Eucharist and a Choral Eucharist. There is a regular Choral Evensong on Wednesdays and one Sunday each month. The Eucharist and other services are also celebrated during the week[1] and the robed choir contributes to its "cathedral style worship".[154] Festival services are popular and known for their standard of liturgy and music, particularly those services which celebrate high points of the church year such as Holy Week and Easter, the Advent carols, the Nine Lessons and Carols, the Christmas Eve Midnight Mass and the patronal festival of St James (son of Zebedee, also known as James the Great) in July. A series of orchestral Masses is held in January.[155]

St James' continues to maintain a formal and sacramental liturgy and has weathered the storm of criticism from a diocese with increasingly "Low church" practices.[48] It is one of the few Sydney Anglican churches that has upheld the norms of mainstream Anglican tradition, including the use of the stole by clergy during services, especially during sacraments such as baptisms and marriages; the Book of Common Prayer and sacred church music, including the singing of hymns from a hymnal.[156]

Theology

The Constitution of the Anglican Church of Australia "commit[s] Anglicans to mainstream Christian orthodoxy", but its ruling principles direct it to that particular tradition within as "represented by the Church of England".[157] The Australian church had to work out the meaning of its common heritage "in the context of the different cultures of the separate colonies"[158] but "the way in which that faith pedigree was appealed to and interpreted ... has highlighted differences."[157] Peter Carnley, former primate of the Anglican Church of Australia, has described Anglicanism's "unique or essential identity" as having "not so much a body of theological teaching, as a style of theological reflection"[159] that goes back to the Elizabethan theologian Richard Hooker.[160] St James' conforms to this Anglican tradition, part of which is a general dislike of what used to be referred to as 'Enthusiasm': that is, a dislike of "pious individualism and emotional exuberance".[161] St James' theological position in the liturgy is evidently consistent with Carnley's explanation that incarnational reality "might be experienced with the aid of aesthetic, symbolic or sacramental aids to worship."[162] Such an adherence to the importance of the sacred and the sublime in worship remains in sharp contradistinction to practice in the surrounding mostly evangelical diocese, which typically eschews beauty and holds to an "ultra-low ecclesiastical aesthetic" that is combined with "ultra-conservative social values".[163][164] Teaching at St James' takes account of both the Biblical and contemporary historical context.[165] In the Sydney diocese, St James's differing view has therefore been controversial since the 19th century as the various rectors led the church towards and away from Anglo-Catholicism.[166] Micklem, for example, renewed Anglo-Catholic churchmanship and Davidson "returned it firmly to a moderate position".[167]

St James' aims to be "an open and inclusive Christian community" that "welcomes all, regardless of age, race, sexual orientation or religion".[168] During the long debate in the diocese about the acceptability of women as priests and also as preachers, for example, women clergy were welcome. One of the first women ordained as a priest in the Anglican Church in Australia, Susanna Pain, served as a deacon at St James'[169] and women in leadership positions in the Anglican Church such as Kay Goldsworthy and Genieve Blackwell, have been invited to preach.[164][170] The current rector contributes to the public debate about the role and responsibilities of the church in a secularised world[171] and in response to statements about same-sex marriage from the Archbishop of Sydney, published a dissenting view.[90][172]

Congregation

In the beginning, convicts, soldiers, governors and civil authorities attended the church; in the 21st century, regular patronage by, and programs for, governors, politicians, the legal community and the homeless create a similarly diverse mix. In 1900, such a congregation was described by the sixth rector as representing "many types, many classes. Here we find rich and poor, old and new, the Governor and the Domain loafer, the passing visitor, and the grandchildren of those whose memorial tablets testify to a long connection with the church." William Carr Smith's observation was that "this makes the congregation a difficult one to handle."[20]

Nevertheless, the congregation provides volunteer labour and donates funds for many of church's activities, including laundry work, library administration, flower arrangements, bell ringing, singing in the parish choir and hospitality for the Sister Freda mission. Furnishings for the chapel in the Sydney Hospital were provided by the parishioners during Carr Smith's time, when he became chaplain to the hospital.[173]

Community service

St James' work for the poor, as well as for the city's legal and medical professions, has been continuous from the 19th century. Since early times work "for the poor of the parish"; the promotion of "overseas and inland missions"; liaison with "the city professions in law and medicine" and running "devotional and discussion groups" has been incorporated into the church's mission.[174] In the 20th century, the ninth and tenth rectors emphasised "the church's responsibility to society" and encouraged St James' role in the city.[175] In the 21st century, these activities have been supplemented by chaplaincy and professional counselling services directed at dealing with the problems associated with the stresses of city life.[176]

The "most direct part of St James' social welfare work" is the Sister Freda Mission, which began in 1899.[173] Among other things, this ministry provides weekly lunches to the needy and a full dinner at Christmas. Sister Freda (Emily Rich) was a member of the Community of the Sisters of the Church, a religious order which started the Collegiate School in Paddington in 1895. Sister Freda and other members of the order took over the organisation of its mission to the homeless in 1899.[177] On Christmas Day in 1901 "about 60 men were entertained at dinner at St James' parish hall, and later in the afternoon 250 unemployed men were treated to tea in the same building by the sisters of the church."[94] After her death in 1936, Sister Freda's name was given to the mission and St James' took over responsibility for its organisation.[173] Since 1954, this service has operated out of the church crypt, relying on donations, including food sourced by OzHarvest, and the efforts of volunteer parishioners.[95]

The church's ministry to Sydney's legal fraternity is facilitated by its proximity to buildings used by the profession, including the Law Courts, which is the main building of the Supreme Court of New South Wales and houses the Sydney registry of the High Court of Australia; the College of Law and the St James Campus of the University of Sydney, which is the former home of Sydney Law School, still mainly used for legal education by the university.[178] Phillip Street, which runs north from the church, is home to a large number of barristers' chambers as well as the Law Society of New South Wales.[179]

Due to this proximity, the church and legal profession have a longstanding relationship, anchored by an annual service to mark the beginning of the legal year which is attended by judges, solicitors and members of the Bar from the Supreme Court of New South Wales in ceremonial attire.[180][181][129] In the 19th century, the relationship was reported in the context of delays to the law and concerns about the need for a suitable set of new courts.[67] In the 20th, it was noted that the "relationship of law and religion" was one of "two co-operating forces, approaching, from different sides, a problem which was common to them both of securing right conduct";[182] and in the 21st century, the Governor still attends special services. Since 1950, there has also been an annual service for the members of the Order of St Michael and St George.[129]

Education

.jpg.webp)

The inscription reads:

Saint James's Grammar School Erected A:D: MDCCCXL [1840] William Grant Broughton D.D. Bishop of Australia

In the 19th century, religious denominations made a major contribution to education at all levels before this was taken over by the state. From its beginnings, St James' was involved in education for both children and adults. Richard Hill, the first incumbent, "began Australia's first kindergarten and William Cape managed a school based on new educational principles".[183][184] Hill worked with the Benevolent Society, the Bible Society, Aboriginals, the Hospital, "various convict establishments and a range of schools," including Industrial Schools.[177] By 1823 Greenway's school building had been erected in Elizabeth Street and the principal St James' School was situated there until 1882, becoming the Anglican "normal" school with more than 600 students and a range of experienced teachers.[31] In secondary education, a Sydney branch of the King's School operated briefly in the Greenway building and Broughton operated the St James' Grammar School in a building erected in Phillip Street. The Grammar School, presided over by C. Kemp was described as "of inestimable value to the then youth of the colony".[20] Broughton also set up St James' College to provide tertiary education for secular students as well as to prepare students for ordination. The St James' School closed in 1882 and the government resumed the Greenway building.[31] Tuition for the students of St Paul's College, University of Sydney was originally provided in the vestry of St James'.[31]

In the 20th century, St James' developed its education program for children and adults and continued them in the 21st century.[185] A Sunday school for children is held in the crypt. Educational activities for adults are offered through the St James' Institute which provides a range of programs open to all to explore the Christian faith and engage in debate about contemporary issues from a theological perspective.[186] For example, in 2012, the Institute hosted a seminar on "Women in the Australian Church: Untold Stories" in conjunction with the International Women's Network and MOWatch.[187][188] In 2013, there was a meeting of "deans and ministers from Anglican churches that serve the business districts in major cities around world" to discuss the churches' response to the Global Financial Crisis.[189]

Past and present clergy

Samuel Marsden delivered the first sermon on 6 July 1824.[190] In 1836 the first (and only) Bishop of Australia, William Grant Broughton, was installed at St James' as there was still no cathedral. Broughton regularly officiated at St James'[12] as at the first ordination of an Anglican priest in Australia (T. Sharpe) on 17 December 1836.[191]

The rector of St James' is assisted by associate rectors (it was not until the 1890s that the title "rector" was used).[42][43] The current (sixteenth) rector is Andrew Sempell and the associate rector is the John Stewart.[192][193]

- 1824–1836 Richard Hill

- 1836–1838 Robert Cartwright

- 1838–1840 George Napoleon Woodd

- 1840–1884 Robert Allwood

- 1885–1895 Henry Latimer Jackson

- 1896–1910 William Carr Smith

- 1910–1916 W.F. Wentworth-Sheilds[194]

- 1917–1937 Philip Arthur Micklem

- 1938–1955 Edwin John Davidson

- 1956–1962 William John Edwards

- 1962–1975 Frank Leslie Cuttriss

- 1976–1983 Howard Charles Hollis

- 1984–1997 Peter John Hughes

- 1997–2001 Richard Hurford

- 2001–2009 Peter Walter Kurti

- 2010–present Andrew John Sempell

Music

St James' has had a strong musical and choral tradition "integral" to its liturgies since the 1820s and is known both for the high standard of the sacred music as well as for its regular public recitals and concerts.[195][196] St James' has a choir, a fine three-manual pipe organ and a peal of bells hung for change ringing.[155] Isaac Nathan, who "constituted himself musical laureate to the colony"[197] and is considered "Australia's first composer", created a musical society at St James' in the 1840s.[198]

Organ

The original organ, installed in the west gallery, was built by John Gray of London and was played for the first time on 7 October 1827. It received the following praise in the colonial newspaper The Australian.

.jpg.webp)

"St. James's new organ pealed its notes of praise for the first time at noon service on Sunday, to an overflowing congregation, more numerous perhaps than any congregation St. James's had ever before witnessed. The organ was not in perfect harmony, owing, in a great measure, to its yet incomplete state. Its intonations, however, in many instances, was full, rich, and harmonious, and those of the congregation were not a few who felt its tones swell on the ear like the welcome voice of a long parted friend!"[199]

The organ was modernised and enlarged in the 1870s by William Davidson. After a number of moves around the galleries, it was placed in what had been intended as the south porch. At the time the church's interior was reconstructed at the turn of the 20th century, it was positioned on either side of the chancel platform at the eastern end where it remains.[119] Organ specialists Hill, Norman & Beard (Aust) Pty Ltd gave the organ a major refurbishment and reconstruction between 1970 and 1971 at a cost of $35,000.[200]

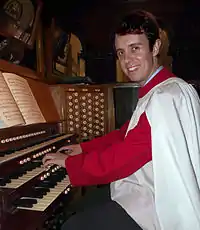

Choir

St James' has had a choir since early colonial times. James Pearson accepted the office of choir leader in 1827 and arranged some of the music that was sung.[201][202][203] He also offered to teach "a few steady persons, of either sex," if they would volunteer to join the choir.[204] In those early days, the choir was a "mixed one, of male and female voices, some of them professional", but by the end of the 19th century, the choristers were all males.[4] Until Anthony Jennings was appointed Director of Music in 1995, the choirmaster was also the organist.[205][206] Some choirmasters, such as James Furley, also composed original works for the choir.[207] Arthur J. Mason served 1898–1907 (and was City Organist 1901–1907),[208] was succeeded by George Faunce Allman in the role.[209]

The current choir is composed of about a dozen semi-professional adults. They sing on Sundays at the 11.00 am Choral Eucharist, Wednesdays at the 6:15 pm Choral Evensong, monthly at the 3.00 pm Choral Evensong held on the last Sunday of the month, as well as at a number of midweek feast days held during the year.[210] In January, during the summer holiday period, St James' presents three full orchestral Masses during which liturgical music by composers such as Mozart, Haydn and Schubert is used for its original purpose and incorporated into the service. On these occasions, the choir is joined by a small orchestra.[211]

On occasion, the St James' choir has combined with other choirs,[212] such as when it joined the choir of St Mary's Cathedral to present Monteverdi's Vespers in 2013.[213] It has recorded CDs,[214] performed with international touring groups such as with the Tallis Scholars' Summer School and broadcast on ABC Radio, both in their own right as well as with leading ensembles such as Australian Baroque Brass.[210]

Musical critique of the choir has appeared in the press from the beginning and continues to the present day. In 1827, one singer was criticised for her diction: "If her pronunciation were as pleasing as her notes, she would be entitled to unqualified praise" wrote a critic in 1827.[215] In 1845, St James' was being described as the "exception" to the prevailing low standard of church music in both England and New South Wales.[216] In 2013, singers from the combined choirs of St James' and St Mary's Cathedral were appraised as creating "a clear, well-defined edge that swirled gloriously".[213]

Music leaders

- 1827–1831 James Pearson

- 1831–1835 William Merritt

- 1836–1844 James and William Johnson

- 1844–1860 James Johnson

- 1860–1874 James Furley

- 1874–? Schofield

- 1876–1897 Hector Maclean

- 1897–1907 Arthur Mason

- 1907–1961 George Faunce Allman

- 1961–1965 Michael Dyer

- 1966–1994 Walter Sutcliffe

- Directors of Music[206]

- 1995 Anthony Jennings

- 1995–1997 David Barmby

- 1997–2007 David Drury

- Head of Music

Bells

The church's eight bells are rung by the Guild of St James' Bellringers which is affiliated with The Australian and New Zealand Association of Bellringers.[220] The tenor bell, weighing 10 cwt, was cast in 1795 by John Rudhall and hung previously in St Paul's Church, Bristol, England. Bells 1 – 7 were cast in 2002 by John Taylor Bellfounders in Loughborough, England.[221] The bells were dedicated on 27 July 2003 and are named after people associated with St James' Church, as follows:[222][223]

- Treble – Francis Greenway sounds the note of G, named for the architect

- 2 – Mary Reibey sounds the note of F#, named for an early pioneer

- 3 – Sister Freda sounds the note of E, named for a Sister of the Church with an important ministry in the City of Sydney

- 4 – King George IV sounds the note of D, named for the king at the time of the church's foundation

- 5 – Richard Hill sounds the note C, named for the first rector of St James'

- 6 – Lachlan Macquarie sounds the note B, named for the governor at the time of the church's foundation

- 7 – Eora sounds the note A, named for the traditional owners of the land

- Tenor – St James sounds the note G, named for the patron saint

There is also the service bell of 4¼ cwt, known as the Mears bell, cast by Thomas Mears II of Whitechapel Bell Foundry in 1820.[221] It was repaired there in 2011.[224]

See also

References

Citations

- "St. James' Anglican Church". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01703. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "St James', Sydney". Sydney Anglican Network. 2014. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- Cochrane 2006, p. 27.

- "A Historic Church". Illustrated Sydney News. 24 June 1893. p. 9. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- "St. James railway station". Sydney Architecture. 2013. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- "Early church codes". NSW Government. 2013. Archived from the original on 13 January 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 7.

- "St Mary's Cathedral – Things to do in Sydney". sydneyforall.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- James, Patrick (21 March 1999). "St. James' (City Railway)". NSW Railway Station Names and Origins. NSWrail.net. Archived from the original on 6 February 2008. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 5.

- "Hundredth Anniversary of Famous Sydney Church". The Sunday Times. 5 October 1919. p. 23. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- "Church history". St James' King Street. 2014. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- The Church 1963, p. 3.

- "King Street court complex". About the Supreme Court. Supreme Court of New South Wales. 2012. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 22.

- Judd & Cable 2000, pp. 6–18.

- Symonds, Edwards (1898). "The Story of the Australian Church (with map)". London: Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- Cable, K.J. (1966). "Hill, Richard (1782–1836)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- Cable & Annable 1999, pp. 8–11.

- Wright, Clyde (18 August 1900). "Restoration of St. James's Church, Sydney". Australian Town and Country Journal. p. 37. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 8-11.

- The Church 1963, p. 7.

- Until Broughton returned from England in 1836 "with the title and authority of Bishop of Australia ... Australia was under the See of Calcutta."

- Kenny, M. J. B. (1966). "Hall, Edward Smith (1786–1860)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 1. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- Cable & Annable 1999, pp. 11–19.

- Cable & Annable 1999, pp. 19–21.

- Dr. Micklem (18 May 1936). "Broughton Centenary". The Sydney Morning Herald). p. 6. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- Cable & Annable 1999, pp. 19–22.

- The Church 1963, p. 9.

- Cable, K.J. (1966). "Allwood, Robert (1803–1891)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 36.

- Samantha Frappell (2012). "O'Connell, Maurice". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Archived from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- "Family Notices". The Sydney Morning Herald. 8 August 1878. p. 1. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- "Marriage of Mr A.K. Finlay and Miss Robinson". Queanbeyan Age (NSW: 1867–1904). 14 August 1878. p. 1. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- "Mr. and Mrs. Finlay". Australian Town and Country Journal. 17 August 1878. p. 17. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- "Item 953: Baptism certificate of Edmund Barton, Parish of Saint James, Sydney 1849". Barton Papers. National Library of Australia. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Cable & Annable 1999, pp. 25–28.

- Porter 1989, p. 39.

- Frame 2007, p. 57.

- Cable, K.J. (1969). "Barker, Frederic (1808–1882)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- Cable & Annable 1999, pp. 26–34.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 9.

- The Church 1963, p. 10.

- The Church 1963, p. 11.

- "Religious". Newcastle Morning Herald & Miners' Advocate. 15 June 1895. p. 11. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- Cable & Annable 1999, pp. 26.

- Cable & Annable 1999, pp. 28.

- Cable & Annable 1999, pp. 34–41.

- St. James' Church (Sydney, NSW) 1919, p. 25.

- The Church 1963, p. 12.

- The Church 1963, p. 21.

- The Church 1963, p. 21–22.

- "The Churches – Centenary of St. James'". The Sydney Morning Herald. 4 October 1919. p. 7. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- Australian Heritage Commission 1981, pp. 2; 96.

- "St. James' Church". The Sydney Morning Herald. 12 February 1901. p. 6. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- Jupp 2001, p. 409.

- The Church 1963, p. 31.

- "Advertising – St James Church, King Street (1819–1919) – Programme of the centenary festival". The Sydney Morning Herald. 4 October 1919. p. 5. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- St. James' Church (Sydney, NSW) 1919.

- "Oxford Movement". The Sydney Morning Herald. NSW. 20 July 1933. p. 8. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- Frappell 1997, p. 133.

- Frappell 1997, p. 131.

- "Weekly pewsheet" (PDF). St James' King Street. 7 July 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- Cable, K. J. (1986). "Micklem, Philip Arthur (1876–1965)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 10. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Fitzgerald 1999, p. 39.

- Julie Blyth (2008). "Wyatt, Annie". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- "The Sydney Law Courts". The Sydney Morning Herald. NSW. 6 August 1895. p. 5. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 27.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 20.

- The Church 1963, p. 13.

- The Church 1963, p. 49.

- "King Gustav". The Sydney Morning Herald. 7 November 1950. p. 9. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- "Gladys Moncrieff's Wedding". The Advocate. 21 May 1924. p. 5. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- "Peer and skating star wed". The Australian Women's Weekly. Sydney. 18 November 1939. p. 13. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- "Theatrical Wedding". The Sydney Morning Herald. 21 May 1924. p. 14. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- "St James Church float at the opening ceremony of the Sydney Harbour Bridge". Digital Collections – Pictures – National Library of Australia. March 1932. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "Late Colonel Vernon". The Sydney Morning Herald. NSW. 20 January 1914. p. 7. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- "Envoy Dies Suddenly". The Sydney Morning Herald. 28 April 1950. p. 1. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- "Funeral of Diplomat". The Sydney Morning Herald. 1 May 1950. p. 3. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- "Funeral of Diplomat". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2 May 1950. p. 5. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- The Order of the state funeral service of his late Excellency Mr. O. C. G. Lundquist, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of Sweden, Monday, 1st May, 1950 at 3 p.m is in the collections of the National Library of Australia (call number JAFp BIO 286)

- "Sir John Kerr dies alone at 76: the storm goes on". The Canberra Times. 26 March 1991. p. 1. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- "Class traitor or saviour? Votes still out". The Canberra Times. 26 March 1991. p. 8. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- Osmond, Warren (16 October 1993). "Six years on, Tutu says thanks". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, NSW. p. 22. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- "St James' Church". The Sydney Morning Herald. 26 July 1897. p. 9. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- "St James's Church Organ". The Sydney Morning Herald. 25 March 1936. p. 7. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- "The Ethics of Voluntary Assisted Dying". The Videos from the Parliamentary Forum – 4 Nov 2013 Part 4: The Reverend Andrew Sempell – Rector St James Anglican Church Sydney (video). Dying with Dignity NSW. 14 November 2013. Archived from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- In February 2014, an information session about refugees and asylum seekers in Australia was chaired by the rector. Former Commonwealth Ombudsman Allan Asher was a participant. Dillon, Sarah (February–March 2014). "Understanding our Neighbours". St James' Parish Connections. St James' Church, Sydney: 1–2, 11.

- Horsburgh, Michael. "On Watching Satan Fall" (PDF). Sermon preached at St James' Church on 7 July 2013. St James' Church, Sydney. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- Jopson, Debra (2 July 2012). "Archbishop challenged over same-sex marriage message". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, NSW. Archived from the original on 9 December 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- "2013 Opening of Law Term – Anglican Church Service". Law Society of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 16.

- "St. James' Church". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 February 1899. p. 8. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- "St James' Church". The Sydney Morning Herald. 26 December 1901. p. 5. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- "Sister Freda Mission". St James' King Street. 2014. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- "2013 Programme" (PDF). St James' Institute. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- Flowers, John (15 February 2012). "Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee". Hansard: Legislative Assembly. Sydney: Parliament of New South Wales. p. 8328. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- Sempell, Andrew. "Long to Reign Over Us" (PDF). Parish Connections (October/November 2015): 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- Marr, David (24 March 2012). "Life of the party, but she was a woman of simple pleasures". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, NSW. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- Apperly & Lind 1971, p. 25.

- Australian Heritage Commission 1981, pp. 2; 95.

- "{{{2}}}". New South Wales Heritage Database. Office of Environment and Heritage.

- "St James Anglican Church, 173 King St, Sydney, NSW, Australia (Place ID 1820)". Australian Heritage Database. Department of the Environment. 21 March 1978. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- The Church 1963, p. 23.

- 2005, Episode 3.

- "Other Banknotes: paper series". Reserve Bank of Australia. 2013. Archived from the original on 27 January 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- Cable & Clarke 1982, p. 31.

- "New stamp series". The Canberra Times. 31 August 1973. p. 9. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- Freeland 1968, pp. 37–38: In comparison with the heights to which Greenway "soared" with his designs for St James', St Matthew's, Windsor and the Hyde Park Barracks, the Old Supreme Court "was formless, pedestrian and dully anonymous".

- Freeland 1968, p. 40.

- Leary & Leary 1972, pp. 34–40.

- Masey, Edward (29 September 1948). "Historic Buildings". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- Freeland 1968, p. 39.

- Judd & Cable 2000, p. 12.

- Apperly, Irving & Reynolds 1989, p. 28.

- Freeland 1968, p. 38.

- Freeland 1968, p. 37.

- The Church 1963, p. 22.

- Cable & Annable 1999, pp. 24–25.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 41.

- Lindsay, Frances (1979). "Carter, Norman St Clair (1875–1963)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- The Church 1963, p. 27.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 38.

- "David Wright – Glass Artist". davidwrightstudio.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- Beverley Sherry (2011). "Stained glass". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- Cable & Annable 1999, pp. 40–41.

- "Magazome: Arts Finely crafted furniture uses local timbers". The Canberra Times. 20 July 1991. p. 42. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 12.

- The Church 1963, p. 18.

- "The Children's Chapel (of St Mary and the Angels)". St James' King Street. 2014. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- "25 iconic projects". International Conservation Services. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- Cable & Clarke 1982, p. 50.

- Gift of Mr & Mrs L.T. Lloyd (The Church 1963, p. 24.)

- "Church Registers: St James Church of England, Sydney, NSW" (PDF). Biographical Database of Australia. November 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- The inscription reads: "To the Glory of God and in loving memory of Keith Kinnaird Mackellar Lieutenant 7th (Princess Royal) Dragoon Guards who was killed in action at Onderstepoort South Africa on the 11th July 1900 in the twentieth year of his age. 'Who shall ascend into the hill of the Lord: or who shall rise up in his holy place? He that hath clean hands and pure heart.'"

- "St. James's Church, Sydney". Australian Town and Country Journal. 8 July 1876. p. 20. Retrieved 8 October 2011. It contains a detailed list of the memorials

- Cable & Clarke 1982, p. 15.

- Memorial plaque to Edmund Beasley Court Kennedy. North wall, St James' Church, Sydney: Executive Government, Legislative Council of New South Wales. 1849. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- Horsburgh, Michael (Winter 1998). "The writing on the wall [St James' Anglican Church, Sydney]". St Mark's Review (174): 11–17. ISSN 0036-3103. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- St. James' Church (Sydney, NSW) 1919, p. 31.

- "Westminster Abbey honours father of modern Australia". Westminster Abbey. Westminster Abbey. 9 July 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Westminster Abbey honours the father of modern Australia" (PDF). Parish Connections. St James' Church, Sydney: 10. August–September 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- "Arthur Phillip Memorial Service". St James' Parish Connections. St James' Church, Sydney: 12–14. October–November 2014. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Cable & Clarke 1982, p. 8.

- "An Act for registering Births, Deaths, and Marriages 3rd December 1855" (PDF). NSW Legislative Council No. XXXIV. Australasian Legal Information Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- Registers of St. James' Anglican Church, King Street, Sydney, N.S.W. [microform], National Library of Australia catalogue records: 1835–1925; 1824–1963, and Baptismal register 1854–1924

- "Sydney's oldest church spire saved". Architecture And Design. 20 October 2010. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Annable, Rosemary (July 2009). "Saving our Spire". Parish Connections, the newsletter of St James' King Street.

- Davey, Melissa (5 April 2011). "Restorers get in touch with the 1820s, with verdigris and vertigo". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, NSW. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- Australian Institute of Architects (1 July 2011). "New centres helping young Australians scoop major NSW Architecture Awards". www.architecture.com.au. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "St James' Church Spire". Design 5 – Architects. 2012. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013. Restoration project sheet Archived 13 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Davey, Melissa (2 July 2011). "National accolade for the building blocks of health care". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, NSW. Archived from the original on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- Churchwardens of St James' Church (March–September 2013). Church Wardens' Report (Report). Sydney.

- Whiteoak & Scott-Maxwell 2003, p. 128.

- "Friends of Music at St James'". fom.org.au. 2013. Archived from the original on 18 August 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- Porter 2011, pp. 10–12.

- Kaye 2002, p. 171.

- Kaye 2002, p. 170.

- Carnley 2004, p. 81.

- Frame 2007, p. 56.

- This third theological tradition (later called the 'Broad Church' or 'Liberal' tradition) is in addition to those created by the "tensions between Evangelicals and Tractarians". It is one which also "claimed its origins in Richard Hooker's appeal to human reason ... as a rational account of the universe." (Frame (2006) p.56)

- Carnley 2004, pp. 70.

- Farrelly, Elizabeth (4 June 2014). "Sydney Anglicans reject the sacred feminine". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 4 June 2014. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- Lindsay & Scarfe 2012, p. 179.

- Sempell, Andrew. "Sermon: "That we may Evermore Live in Him and He in Us"" (PDF). St James' Church, Sydney. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- "St. James' Church". The Sydney Morning Herald. NSW. 1 August 1932. p. 6. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- Cable & Annable 1999, pp. 13,16.

- "Welcome". St James' King Street. 2014. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- Harris, Eleri (9 March 2012). "One for the ladies: 20 years of women's ordination in Australia". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 15 September 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

Although Pain was an ordained priest in the Diocese of Canberra and Goulburn at the time, in the Sydney diocese she was only allowed to minister as a deacon, the practical effect of which was that she was not permitted to preside at the Eucharist.

- Baird, Julia (1 December 2012). "Going backwards into the future". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, NSW. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- Sempell, Andrew (September 2012). "God, Society and Secularism". St Mark's Review. 3 (221): 56–65.

- Sempell, Andrew (20 June 2012). "Rector's response to Archbishop regarding redefining marriage" (PDF). St James' Church official website. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- The Church 1963, p. 17.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 11.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 17.

- "Counselling at St James" (PDF). St James' King Street. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 30.

- "Map of the New South Wales – Sydney City Campus". College of Law. 2013. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "Homepage of the Law Society of NSW". The Law Society of New South Wales. 2013. Archived from the original on 21 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "Law Term Opens". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 February 1940. p. 9. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- "Law Term Opens". The Sydney Morning Herald. 12 February 1946. p. 7. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- "Opening of law Term". The Sydney Morning Herald. NSW. 12 February 1936. p. 9. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Judd & Cable 2000, p. 14.

- Goodin, V. W. E. (1966). "Cape, William Timothy (1806–1863)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. pp. 209–210. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- "Education". St James' King Street. 2014. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- "St James' Institute". St James' King Street. 2014. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- "Twentieth anniversary events 10 MAY - Sydney 'Women in the Australian Church: the Untold Stories'". MOWatch. Archived from the original on 26 January 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- St James' Institute 2012 Program pp. 10–11

- Andrew West (presenter) (18 April 2012). "The church and corporate greed". Radio National. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- "The Court House & St James Church, Hyde Park Sydney, 1839 pencil drawing by Thomas Hatfield (SSV1/ Pub Ct H/2)". Gallery of Churches. State Library of New South Wales. 2013. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- The Church 1944, p. 6.

- "Clergy: The Reverend Andrew Sempell". St James' King Street. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- "Dean takes on new challenge". Central Western Daily. 15 March 2010. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- "Francis was to sign his name as Wentworth-Sheilds."Cable, K.J. (1990). "Wentworth-Shields, Wentworth Francis (1867–1944)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 24.

- "St. James' Church". The Sydney Morning Herald. 26 July 1897. p. 9. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- Catherine Mackerras (1967). "'Nathan, Isaac (1790–1864)'". Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography. Australian National University. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- Graeme Skinner (2008). "Nathan, Isaac". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- "Untitled". The Australian. 10 October 1827. p. 3. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- Mark Dunn (2008). "St James Anglican church Queens Square". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- "Untitled". The Monitor. 9 March 1827. p. 8. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- Skinner, Graeme. "A chronological checklist of colonial Australian musical compositions, arrangements, and transcriptions c. 1788–1840". Austral Harmony Music and musicians in colonial Australia. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- Bebbington 1997, p. 120.

- "Tristan d'Acunha". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW: 1803–1842). 21 July 1829. p. 2. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- Drummond 1978, p. 53.

- Cable & Annable 1999, p. 25.

- Furley, James (c. 1870). "Nunc dimittis". Composition for St James' choir. J. R. Clarke (music publisher). Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- "Church News". The Sydney Morning Herald. 9 January 1901. p. 5. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- Cable & Clarke 1982, p. 40.

- "Information about the choir" (PDF). St James' King Street. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- "Orchestral masses". St James' King Street. 2014. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- "Combined choirs". The Sydney Morning Herald. 25 August 1933. p. 4. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- McCallum, Peter (16 August 2013). "Brilliant compendium of Monteverdi's genius". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, NSW. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- The CDs are entitled Christmas at St James (2003), No Ordinary Sunday (2004), Any Given Sunday, A German Requiem by Johannes Brahms and Metamorphosis (2012), which includes original compositions by St James' choristers.

- "Domestic Intelligence". The Monitor (Evening ed.). 3 September 1827. p. 3. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- Rushworth 1988, p. 366.

- "St James' Music Staff". St James' Church, Sydney. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- "About The Consort of Melbourne". The Consort of Melbourne. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2014.