Arthur Phillip

Admiral Arthur Phillip (11 October 1738 – 31 August 1814) was an English Royal Navy officer and the first Governor of New South Wales who led the British settlement and colonisation of Australia. He established a British penal colony that later became the city of Sydney, Australia.[1]

Arthur Phillip | |

|---|---|

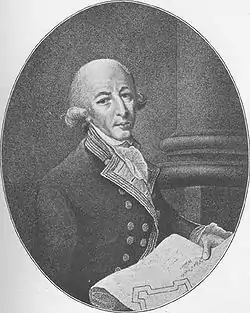

Captain Arthur Phillip, 1786, by Francis Wheatley | |

| 1st Governor of New South Wales | |

| In office 7 February 1788 – 10 December 1792 | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | Position Established |

| Succeeded by | John Hunter |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 11 October 1738 Cheapside, London, England |

| Died | 31 August 1814 (aged 75) Bath, Somerset, England |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Branch/service | Royal Navy |

| Rank | Admiral |

| Battles/wars | |

After much experience at sea, Phillip led the First Fleet as Governor-designate in the Australian settlement of New South Wales. In January 1788, he selected its location to be Port Jackson (encompassing Sydney Harbour).[2]

Phillip was a far-sighted governor who soon saw that New South Wales would need a civil administration and a system for emancipating the convicts. But his plan to bring skilled tradesmen on the voyage had been rejected, and he faced immense problems of labour, discipline and supply.

The arrival of the Second and Third Fleets placed new pressures on the scarce local resources, but by the time Phillip sailed home in December 1792, the colony was taking shape, with official land-grants and systematic farming and water-supply.

Phillip retired in 1805, but continued to correspond with his friends in New South Wales and to promote the colony's interests.

Early life

Captain Arthur Phillip was born on 11 October 1738, the youngest of two children to Jacob Phillip and Elizabeth Breach. His father Jacob was a languages teacher from Frankfurt who may also have served in the Royal Navy as an able seaman and purser's steward. His mother Elizabeth was the widow of an ordinary seaman, John Herbert, who had served in Jamaica aboard HMS Tartar and died of disease on 13 August 1732. At the time of Arthur Phillip's birth, his family maintained a modest existence as tenants near Cheapside in the City of London.[3]

There are no surviving records of Phillip's early childhood. His father Jacob died in 1739, after which the Phillip family may have fallen on hard times.[4] On 22 June 1751 Arthur was accepted into the Greenwich Hospital School, a charity school for the sons of indigent seafarers.[5] In keeping with the school's curriculum, his education was focused on literacy, arithmetic and navigational skills, including cartography. He was a competent student and something of a perfectionist. His headmaster, Reverend Francis Swinden observed that in personality Phillip was "unassuming, reasonable, business-like to the smallest degree in everything he undertakes".[6]

Phillip remained at the Greenwich School for two and a half years, considerably longer than the average student stay of twelve months.[7] At the end of 1753 he was granted a seven-year indenture as an apprentice aboard Fortune, a 210-ton whaling vessel commanded by merchant mariner Wiliam Readhead. He left the Greenwich School on 1 December and spent the winter aboard the Fortune awaiting the commencement of the 1754 whaling season.[8]

First voyages

Phillip spent the summer of 1754 hunting whales near Svalbard in the Barents Sea.[9] As an apprentice, his responsibilities included stripping blubber from whale carcasses and helping to pack it into barrels.[10] Food was scarce and Fortune's thirty crew members supplemented their diet with bird's eggs, scurvy grass and where possible, reindeer.[11] The ship returned to England on 20 July 1754. The whaling crew were paid off and replaced with twelve sailors for a winter voyage to the Mediterranean. As an apprentice, Phillip remained aboard as Fortune undertook an outward trading voyage to Barcelona and Livorno carrying salt and raisins, returning via Rotterdam with a cargo of grains and citrus.[12] The ship returned to England in April 1755 and sailed immediately for Svalbard for that year's whale hunt. Phillip was still a member of the crew, but abandoned his apprenticeship when the ship returned to England on 27 July.[13] On 16 October he enlisted in the Royal Navy and was assigned the rank of ordinary seaman aboard the 68-gun HMS Buckingham.[14]

As a member of Buckingham's crew, Phillip saw action in the Seven Years' War, including the Battle of Minorca in 1756. By 1762 he had transferred to HMS Stirling Castle, and was promoted to Lieutenant in recognition of active service in the Battle of Havana.[9] The War ended in 1763 and Phillip returned to England on half pay. In July 1763 he married Margaret Denison, a widow 16 years his senior, and moved to Glasshayes in Lyndhurst, Hampshire, establishing a farm there. The marriage was unhappy, and the couple separated in 1769 when Phillip returned to the Navy.[9] The following year he was posted as second lieutenant aboard HMS Egmont, a newly built 74-gun ship of the line.[9]

In 1774 Phillip joined the Portuguese Navy as a captain, serving in the War against Spain. While with the Portuguese Navy, Phillip commanded a frigate, the Nossa Senhora do Pilar. On this ship he took a detachment of troops from Rio de Janeiro to Colonia do Sacramento on the Río de la Plata (opposite Buenos Aires) to relieve the garrison there. This voyage also conveyed a consignment of convicts assigned to carry out work at Colonia. During a storm encountered in the course of the voyage, the convicts assisted in working the ship and, on arrival at Colonia, Phillip recommended that they be rewarded for saving the ship by remission of their sentences.[15] A garbled version of this eventually found its way into the English press when Phillip was appointed in 1786 to lead the expedition to Sydney.[16] Phillip played a leading part in the capture of the Spanish ship San Agustín, on 19 April 1777, off Santa Catarina. The San Agustin was commissioned into the Portuguese Navy as the Santo Agostinho, and command of her was given to Phillip. The action was reported in the English press:

Madrid, 28 Aug.. Letters from Lisbon bring the following Account from Rio Janeiro: That the St. Augustine, of 70 Guns, having been separated from the Squadron of M. Casa Tilly, was attacked by two Portugueze Ships, against which they defended themselves for a Day and a Night, but being next Day surrounded by the Portugueze Fleet, was obliged to surrender.[17]

In 1778 Britain was again at war, and Phillip was recalled to active service, and in 1779 obtained his first command, HMS Basilisk. He was promoted to post-captain on 30 November 1781 and given command of HMS Europa.[18][19]

Correspondence of Luís, 2nd Marquis Lavradio, Viceroy of Brazil, 1778.

In July 1782, in a change of government, Thomas Townshend became Secretary of State for Home and American Affairs, and assumed responsibility for organising an expedition against Spanish America. Like his predecessor, Lord Germain, he turned for advice to Arthur Phillip.[21] A letter from Phillip to Sandwich of 17 January 1781 records Phillip's loan to Sandwich of his charts of the Plata and Brazilian coasts for use in organising the expedition.[22] Phillip's plan was for a squadron of three ships of the line and a frigate to mount a raid on Buenos Aires and Monte Video, then to proceed to the coasts of Chile, Peru and Mexico to maraud, and ultimately to cross the Pacific to join the British Navy's East India squadron for an attack on Manila.[23] The expedition, consisting of the Grafton, 70 guns, Elizabeth, 74 guns, Europe, 64 guns, and the frigate Iphigenia, sailed on 16 January 1783, under the command of Commodore Robert Kingsmill.[24] Phillip was given command of the 64-gun HMS Europa, or Europe.[25] Shortly after sailing, an armistice was concluded between Great Britain and Spain. Phillip learnt of this in April when he put in for storm repairs at Rio de Janeiro. Phillip wrote to Townshend from Rio de Janeiro on 25 April 1783, expressing his disappointment that the ending of the American War had robbed him of the opportunity for naval glory in South America.[26]

After his return to England from India in April 1784, Phillip remained in close contact with Townshend, now Lord Sydney, and the Home Office Under Secretary, Evan Nepean. From October 1784 to September 1786 he was employed by Nepean, who was in charge of the Secret Service relating to the Bourbon Powers, France and Spain, to spy on the French naval arsenals at Toulon and other ports.[27] There was fear that Britain would soon be at war with these powers as a consequence of the Batavian Revolution in the Netherlands.[28]

Portraits of the time depict Phillip as shorter than average, with an olive complexion, dark eyes and a "smooth pear of a skull".[9][29] His features were dominated by a large and fleshy nose, and by a pronounced lower lip.[29]

Colonial service

At this time, Lord Sandwich, together with the President of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Banks, was advocating establishment of a British colony in New South Wales.[30] A colony there would be of great assistance to the British Navy in facilitating attacks on the Spanish possessions in Chile and Peru, as Banks's collaborators, James Matra, Captain Sir George Young and Sir John Call pointed out in written proposals on the subject. The British Government took the decision to settle what is now Australia and found the Botany Bay colony in August 1786.[31] Lord Sydney, as Secretary of State for the Home Office, was the minister in charge, and in September 1786 he appointed Phillip commodore of the fleet which was to transport the convicts and soldiers who were to be the new settlers to Botany Bay. Upon arrival there, Phillip was to assume the powers of Captain General and Governor in Chief of the new colony. A subsidiary colony was to be founded on Norfolk Island, as recommended by Sir John Call, to take advantage for naval purposes of that island's native flax (harakeke) and timber.

In October 1786, Phillip was appointed captain of HMS Sirius and named Governor-designate of New South Wales, the proposed British colony on the east coast of Australia, by Lord Sydney, the Home Secretary.[32][33]

Phillip had a very difficult time assembling the fleet which was to make the eight-month sea voyage to Australia. Everything a new colony might need had to be taken, since Phillip had no real idea of what he might find when he got there. There were few funds available for equipping the expedition. His suggestion that people with experience in farming, building and crafts be included was rejected. Most of the 772 convicts (of whom 732 survived the voyage) were petty thieves from the London slums. Phillip was accompanied by a contingent of marines and a handful of other officers who were to administer the colony.

The 11 ships of the First Fleet set sail from Portsmouth on 13 May 1787.[34][35] The fleet called at Rio de Janeiro for supplies from 6 August to 4 September.[36] The leading ship, HMS Supply reached Botany Bay setting up camp on the Kurnell Peninsula, on 18 January 1788.[37] Phillip soon decided that this site, chosen on the recommendation of Sir Joseph Banks, who had accompanied James Cook in 1770, was not suitable, since it had poor soil, no secure anchorage and no reliable water source. After some exploration Phillip decided to go on to Port Jackson, and on 26 January the marines and convicts landed at Sydney Cove, which Phillip named after Lord Sydney.[38]

Governor of New South Wales

Shortly after landing and establishing the settlement at Port Jackson, on 15 February 1788, Phillip sent Lieutenant Philip Gidley King with eight free men and a number of convicts to establish the second British colony in the Pacific at Norfolk Island. This was partly in response to a perceived threat of losing Norfolk Island to the French and partly to establish an alternative food source for the mainland colony.

The early days of the settlement in New South Wales were chaotic and difficult. With limited supplies, the cultivation of food was imperative, but the soils around Sydney were poor, the climate was unfamiliar, and moreover very few of the convicts had any knowledge of agriculture. The colony was on the verge of outright starvation for an extended period. The marines, poorly disciplined themselves in many cases, were not interested in convict discipline. Almost at once, therefore, Phillip had to appoint overseers from among the ranks of the convicts to get the others working. This was the beginning of the process of convict emancipation which was to culminate in the reforms of Lachlan Macquarie after 1811.

Phillip showed in other ways that he recognised that New South Wales could not be run simply as a prison camp. Lord Sydney, often criticised as an ineffectual incompetent, had made one fundamental decision about the settlement that was to influence it beneficially from the start. Instead of just establishing it as a military prison, he provided for a civil administration, with courts of law. Two convicts, Henry and Susannah Kable, sought to sue Duncan Sinclair, the captain of Alexander, for stealing their possessions during the voyage. Convicts in Britain had no right to sue, and Sinclair had boasted that he could not be sued by them. Despite this, the court found for the plaintiffs and ordered the captain to make restitution for the loss of their possessions.[39]

Further, soon after Lord Sydney appointed him governor of New South Wales, Arthur Phillip drew up a detailed memorandum of his plans for the proposed new colony. In one paragraph he wrote: "The laws of this country [England] will of course, be introduced in [New] South Wales, and there is one that I would wish to take place from the moment his Majesty's forces take possession of the country: That there can be no slavery in a free land, and consequently no slaves."[40] Nevertheless, Phillip believed in severe discipline; floggings and hangings were commonplace, although Phillip commuted many death sentences.

Phillip also had to adopt a policy towards the Eora Aboriginal people, who lived around the waters of Sydney Harbour.[2] Phillip ordered that they must be well treated, and that anyone killing Aboriginal people would be hanged. Phillip befriended an Eora man called Bennelong,[2] and later took him to England. On the beach at Manly, a misunderstanding arose and Phillip was speared in the shoulder: but he ordered his men not to retaliate.[41] Phillip went some way towards winning the trust of the Eora, although they remained wary of the settlers. Soon, a virulent disease, smallpox that was believed to be on account of the white settlers, and other European-introduced epidemics, ravaged the Eora population (see History of smallpox in Australia).

The Governor's main problem was with his own military officers, who wanted large grants of land, which Phillip had not been authorised to grant. Scurvy broke out, and in October 1788 Phillip had to send Sirius to Cape Town for supplies, and strict rationing was introduced, with thefts of food punished by hanging. He recorded: "The living conditions need to improve or my men won't work as hard, so I have come to a conclusion that I must hire surgeons to fix the convicts."

Stabilising the colony

Phillip insisted that no retaliation be taken to avenge his own non-fatal spearing. Convict John MacIntyre had been fatally speared during a hunting expedition by unknown Aboriginal people apparently without provocation. MacIntyre swore on his death bed that he had done them no harm, but marine officer Watkin Tench was suspicious of the claim. Tench was sent on a punitive expedition but finding no Aboriginal people other than Bennelong took no action.[42]

Phillip, growing frustrated with the burdens of upholding a colony and his health suffering, resigned soon after this episode.[43][44]

By 1790 the situation had stabilised. The population of about 2,000 was adequately housed and fresh food was being grown. Phillip assigned a convict, James Ruse, land at Rose Hill (now Parramatta) to establish proper farming, and when Ruse succeeded he received the first land grant in the colony. Other convicts followed his example. Sirius was wrecked in March 1790 at the satellite settlement of Norfolk Island, depriving Phillip of vital supplies. In June 1790 the Second Fleet arrived with hundreds more convicts, most of them too sick to work.

By December 1790 Phillip was ready to return to England, but the colony had largely been forgotten in London and no instructions reached him, so he carried on. In 1791 he was advised that the government would send out two convoys of convicts annually, plus adequate supplies. But July, when the vessels of the Third Fleet began to arrive, with 2,000 more convicts, food again ran short, and he had to send the ship Atlantic to Calcutta for supplies.[45]

By 1792 the colony was well established, though Sydney remained an unplanned huddle of wooden huts and tents. The whaling industry was established, ships were visiting Sydney to trade, and convicts whose sentences had expired were taking up farming. John Macarthur and other officers were importing sheep and beginning to grow wool. The colony was still very short of skilled farmers, craftsmen and tradesmen, and the convicts continued to work as little as possible, even though they were working mainly to grow their own food.

In late 1792, Phillip, whose health was suffering, relinquished his governorship and sailed for England on the ship Atlantic, taking with him many specimens of plants and animals. He also took Bennelong and his friend Yemmerrawanne, another young Indigenous Australian who, unlike Bennelong, would succumb to English weather and disease and not live to make the journey home. The European population of New South Wales at his departure was 4,221, of whom 3,099 were convicts. The early years of the colony had been years of struggle and hardship, but the worst was over, and there were no further famines in New South Wales. Phillip arrived in London in May 1793. He tendered his formal resignation and was granted a pension of £500 a year.[46]

Later life and death

Phillip's estranged wife, Margaret, had died in 1792 and was buried in St Beuno's Churchyard, Llanycil, Bala, Merionethshire.[47] In 1794 Phillip married Isabella Whitehead, and lived for a time at Bath. His health gradually recovered and in 1796 he went back to sea, holding a series of commands and responsible posts in the wars against the French. In January 1799 he became a Rear-Admiral. In 1805, aged 67, he retired from the Navy with the rank of Admiral of the Blue, and spent most of the rest of his life in Bath. He continued to correspond with friends in New South Wales and to promote the colony's interests with government officials.

Phillip died in Bath in 1814.[48] His Last Will and Testament has been transcribed and is online.[49]

Phillip was buried in St Nicholas's Church, Bathampton. Forgotten for many years, the grave was discovered in 1897[50] and the Premier of New South Wales, Sir Henry Parkes, had it restored. An annual service of remembrance is held here around Phillip's birthdate by the Britain–Australia Society to commemorate his life.

In 2007, Geoffrey Robertson QC alleged that Phillip's remains are no longer in St Nicholas Church, Bathampton and have been lost: "Captain Arthur Phillip is not where the ledger stone says he is: it may be that he is buried somewhere outside, it may simply be that he is simply lost. But he is not where Australians have been led to believe that he now lies."[51]

Legacy

A number of places in Australia bear Phillip's name, including Port Phillip, Phillip Island (Victoria), Phillip Island (Norfolk Island), Phillip Street in Sydney, the federal electorate of Phillip (1949–1993), the suburb of Phillip in Canberra, the Governor Phillip Tower building in Sydney, and many streets, parks and schools including a state high school in Parramatta. A monument to Phillip in Bath Abbey Church was unveiled in 1937. Another was unveiled at St Mildred's Church, Bread St, London, in 1932; that church was destroyed in the London Blitz in 1940, but the principal elements of the monument were re-erected at the west end of Watling Street, near Saint Paul's Cathedral, in 1968. A different bust and memorial is inside the nearby church of St Mary-le-Bow.[52] There is a statue of him in the Botanic Gardens, Sydney. There is a portrait of him by Francis Wheatley in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Percival Serle wrote of Phillip in his Dictionary of Australian Biography:

Steadfast in mind, modest, without self seeking, Phillip had imagination enough to conceive what the settlement might become, and the common sense to realize what at the moment was possible and expedient. When almost everyone was complaining he never himself complained, when all feared disaster he could still hopefully go on with his work. He was sent out to found a convict settlement, he laid the foundations of a great dominion.[53]

Michael Pembroke's biography of Phillip adds that he was also a highly skilled international spy employed by the British government.[54]

200th anniversary

As part of a series of events on the bicentenary of his death, a memorial was dedicated in Westminster Abbey on 9 July 2014.[55][56] In the service the Dean of Westminster, Very Reverend Dr John Hall, described Phillip as: "This modest, yet world-class seaman, linguist, and patriot, whose selfless service laid the secure foundations on which was developed the Commonwealth of Australia, will always be remembered and honoured alongside other pioneers and inventors here in the Nave: David Livingstone, Thomas Cochrane, and Isaac Newton."[55][57]

A similar memorial was unveiled by the outgoing 37th Governor of New South Wales, Marie Bashir, in St James' Church, Sydney on 31 August 2014.[58]

A bronze bust was installed at the Museum of Sydney,[59] and a full-day symposium planned on his contributions to the founding of modern Australia.[60]

In popular culture

Phillip is a principal character in the 1953 film Botany Bay.

Phillip is a prominent character in Timberlake Wertenbaker's play Our Country's Good, in which he commissions Lieutenant Ralph Clark to stage a production of The Recruiting Officer. He is shown as compassionate and just, but receives little support from his fellow officers.

Phillip is referred to in the John Williamson song "Chains Around My Ankle".

Phillip is a prominent character in the 2005 film The Incredible Journey of Mary Bryant where he is portrayed by Sam Neill.

Kate Grenville's 2008 novel The Lieutenant portrays Phillip through the character Commodore James Gilbert.

Phillip is a prominent character in the 2015 mini-series Banished where he is portrayed by David Wenham.

Memorials

The Arthur Phillip memorial on the wall of the Australia Chapel, Bathampton

The Arthur Phillip memorial on the wall of the Australia Chapel, Bathampton Tomb of Arthur Phillip in St Nicholas Church, Bathampton

Tomb of Arthur Phillip in St Nicholas Church, Bathampton Bust of Phillip at St Mary-le-Bow Church in London.

Bust of Phillip at St Mary-le-Bow Church in London. Memorial plaque to Governor Phillip in St James' Church, Sydney

Memorial plaque to Governor Phillip in St James' Church, Sydney

References

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (22 May 1944). "The Gilberts & Marshalls: A distinguished historian recalls the past of two recently captured Pacific groups". Life Magazine. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Leila Berney (10 October 2014). "On this day: Arthur Phillip born". Australian Geographic. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Pembroke 2013, p. 5

- Parker 2009, pp. 2–3

- Pembroke 2013, p. 9

- Correspondence, Rev. Francis Swinden, 22 June 1753, cited in Pembroke 2013, p. 12

- Parker 2009, p. 4

- Pembroke 2013, p. 12

- Tink 2009, pp. 30–31

- Pembroke 2013, p. 15

- Frost 1987, p. 16

- Frost 1987, p. 22

- Frost 1987, p. 25

- Parker 2009, p. 5.

- Gazeta de Lisboa, 3 de Abril de 1787: Maurine Goldston-Morris, OAM, The Life of Admiral Arthur Phillip, RN, 1738–1814, Naval Historical Society of Australia Monograph No.58, Garden Island [1997].

- See for example, The World, 16 April 1789: "BOTANY BAY.— Mr. Philip, who has this command, has the aid of experience. He had a similar expedition entrusted him by PORTUGAL, to carry convicts to South America.".

- The St. James's Chronicle, The London Chronicle, The Daily Advertiser, The Gazetteer and The Public Advertiser, 16 September 1777.

- "East India Trade". The World. B. MIllan, London. 1 April 1787. p. 3.

- King, Robert J. (25–29 October 1999). Arthur Phillip Defensor de Colónia, Governador de Nova Gales do Sul [Arthur Phillip: Defender of Colônia, Governor of New South Wales] (Speech). V Simpósio de HistóriaMarítimo e Naval Iber-americano. Ilha Fiscal, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Vancouver Island University.

- Correspondence, Luís de Almeida Portugal Soares de Alarcão d'Eça e Melo Silva Mascarenhas, 2nd Marquess of Lavradio, 1778. Cited in Tink 2009, p. 31

- Viscount Keppel, First Lord of the Admiralty, to Townshend, 25 September 1782; Clements Library (Ann Arbor), Sydney Papers, 9; British Library, India and Oriental, H 175, f.237. Cited in Frost 1995, p. 114

- Phillip to Sandwich, 17 January 1781; National Maritime Museum (Greenwich), Sandwich Papers, F/26/23.

- Blankett to Shelburne, August 1782; Clements Library (Ann Arbor), Sydney Papers, 9; quoted in Frost 1987, p. 114.

- Admiralty Lords to Kingsmill, 17 December 1782, National Archives, Kew, ADM 2/113: 522–3; Kingsmill to Admiralty Lords, 1 January 1783, National Archives, Kew, ADM 1/2015; Keppel to Middleton, 17 December 1782, National Archives, Kew, HO 28/2: 410–1; quoted in Alan Frost 1987, p. 114.

- National Archives, Kew, ADM 51/354; ADM 2/113; quoted in Alan Frost 1987, p. 114. The departure of the squadron from Portsmouth was reported in The General Evening Post, The London Chronicle, 18 January, The Morning Post, 20 January 1783; Phillip's return to Portsmouth in the Europe was reported in The Whitehall Evening Post, 24 April 1784.

- India Office Records, H 175, f.237; quoted in Alan Frost, Convicts & Empire: A Naval Question, 1776 1811, Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1980, p. 209. Phillip used the contemporary Portuguese spelling for Montevideo.

- Frost 1987, pp. 129–133

- Frost 1980, pp. 115–116, 129

- Hughes 1986, p. 66

- James Matra to Banks, 28 July 1783, British Library Additional MS 33979: 206. Cited in Frost 1995, p. 110

- George Burnett Barton (1889). "History of New South Wales From the Records, Volume I - Governor Phillip - Chapter 1.4". Project Gutenberg of Australia. Charles Potter, Government Printer. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Fletcher, B.H. (1967). "Phillip, Arthur (1738–1814)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 2. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 25 April 2019 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- "1790 HMS Sirius Anchor and Cannon". Objects Through Time. Migration Heritage Centre NSW. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- "The First Fleet". Project Gutenberg Australia. 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Arthur Phillip (1789). "The Voyage of Governor Phillip To Botany Bay with An Account of the Establishment of the Colonies of Port Jackson and Norfolk Island - Chapter II". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Robert J. King, “Arthur Phillip and the First Fleet at Rio de Janeiro”, Map Matters, Issue 35, Spring 2018, pp. 10–16.

- The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay With an Account of the Establishment of the Colonies of Port Jackson and Norfolk Island (1789) – from Project Gutenberg

- "Geographical Names Register Extract - Sydney". Place Name Search. Geographical Names Board of New South Wales. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- "Cable v. Sinclair [1788] NSWKR 7; [1788] NSWSupC 7". Macquarie University Law School. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Britton (ed.) 1978, p. 53

- Tink, Andrew (2009). Cavalier, Rodney (ed.). The Governors of New South Wales. The Federation Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 9781862877436.

- Watkin Tench. A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson (PDF).

- First Australians. Blackfella Films, SBS, and Screen Australia. 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- Watkin Tench, 1788 (ed: Tim Flannery), 1996, ISBN 1-875847-27-8, p. 167

- Hunter, Chapter XXIII

- Michael Pembroke, Arthur Phillip – Sailor, Mercenary, Governor, Spy, Melbourne, Hardie Grant Books, 2013.

- Michael Flynn, "New perspectives on Arthur Phillip, first Governor of New South Wales [Series of parts]: Part 1: Wives, graves and ghosts." Descent, Volume 43 Issue 2 (June 2013) : 65–81.

- Broughton, W. (1 April 1815). "Sydney: Sitting Magistrate W. Broughton Esq". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. G. Howe. p. 2. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- "The Last Will and Testament of Admiral Arthur Phillip a.k.a. Governor Arthur Phillip". spanglefish.com. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- St Nicholas Church, Bathampton, Burial place of Arthur Phillip

- "Lost the plot - story transcript". 60 Minutes. Ninemsn. 22 April 2007. Archived from the original on 30 January 2008. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Details of move

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Phillip, Arthur (1738–1814), admiral, and first governor of New South Wales". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Project Gutenberg Australia. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- Pembroke, Michael (2013). Arthur Phillip: Sailor, Mercenary, Governor, Spy. Melbourne: Hardie Grant. ISBN 978-1-74358-066-0.

- "Westminster Abbey honours father of modern Australia". Westminster Abbey. Westminster Abbey. 9 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- Withington, Ron (2014). "Peerless Pilgrimage" (PDF). Britain-Australia Society. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Westminster Abbey honours the father of modern Australia" (PDF). St James' Parish Connections: 10. August–September 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- "Arthur Phillip Memorial Service". St James' Parish Connections: 12–14. October–November 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Decent, Tom (28 August 2014). "Arthur Phillip, NSW's first governor, memorialised with bronze bust". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- "The First Governor – A Bicentenary Symposium on Arthur Phillip". Museum of Sydney. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

Bibliography

- Becke, Louis; Jeffery, Walter (1899). . Builders of Great Britain. London, England: T. Fisher Unwin.

- Britton, Alex R., ed. (1978). Historical records of New South Wales. Vol. 1, part 2. Phillip, 1783–1792. Lansdown Slattery & Co. p. 56. OCLC 219911274.

- Frost, Alan (1980). Convicts and empire : a naval question, 1776–1811. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195542554.

- Frost, Alan (1987). Arthur Phillip, 1738–1814 : his voyaging. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195547016.

- Frost, Alan; Moutinho, Isabel (1995). The precarious life of James Mario Matra : voyager with Cook, American loyalist, servant of empire. The Miegunyah Press. ISBN 9780522846676.

- Hunter, John (1793), An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island, London, England: Printed for John Stockdale, OCLC 154257649, OL 8025878W

- Parker, Derek (2009). Arthur Phillip: Australia's first governor. Woodslane Press. ISBN 9781921203992.

- Pembroke, Michael (2013). Arthur Phillip: sailor, mercenary, governor, spy. Hardie Grant Books. ISBN 9781742705088.

- Tink, Andrew (2009). Cavalier, Rodney (ed.). The Governors of New South Wales. The Federation Press. ISBN 9781862877436.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Arthur Phillip |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arthur Phillip. |

- Works by Arthur Phillip at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Arthur Phillip at Internet Archive

- Arthur Phillip High School, Parramatta – state high (years 7–12) school named for Phillip

- B. H. Fletcher, 'Phillip, Arthur (1738–1814)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 2, Melbourne University Press, 1967, pp 326–333.

- Royal Navy History Biographical Memoir of Arthur Phillip, Esq.

- The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay – National Museum of Australia

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New district | Governor of New South Wales 1788–1792 |

Succeeded by John Hunter |