Church bell

A church bell in the Christian tradition is a bell which is rung in a church for a variety of ceremonial purposes, and can be heard outside the building. Traditionally they are used to call worshippers to the church for a communal service, and to announce the fixed times of daily Christian prayer, called the canonical hours, which number seven and are contained in breviaries. They are also rung on special occasions such as a wedding, or a funeral service. In some religious traditions they are used within the liturgy of the church service to signify to people that a particular part of the service has been reached.[1] The ringing of church bells, in the Christian tradition, is also believed to drive out demons.[2][3][4]

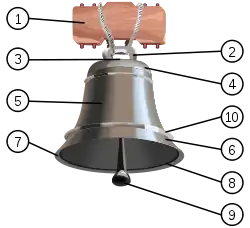

The traditional European church bell (see cutaway drawing) used in Christian churches worldwide consists of a cup-shaped metal resonator with a pivoted clapper hanging inside which strikes the sides when the bell is swung. It is hung within a steeple or belltower of a church or religious building,[5] so the sound can reach a wide area. Such bells are either fixed in position ("hung dead") or hung from a pivoted beam (the "headstock") so they can swing to and fro. A rope hangs from a lever or wheel attached to the headstock, and when the bell ringer pulls on the rope the bell swings back and forth and the clapper hits the inside, sounding the bell. Bells that are hung dead are normally sounded by hitting the sound bow with a hammer or occasionally by a rope which pulls the internal clapper against the bell.

A church may have a single bell, or a collection of bells which are tuned to a common scale. They may be stationary and chimed, rung randomly by swinging through a small arc, or swung through a full circle to enable the high degree of control of English change ringing.

Before modern communications, church bells were a common way to call the community together for all purposes, both sacred and secular.

Uses and traditions

Call to prayer

Oriental Orthodox Christians, such as Copts and Indians, use a breviary such as the Agpeya and Shehimo to pray the canonical hours seven times a day while facing in the eastward direction; church bells are tolled, especially in monasteries, to mark these seven fixed prayer times.[6][7]

In Christianity, some churches ring their church bells from belltowers three times a day, at 9 am, 12 pm and 3 pm to summon the Christian faithful to recite the Lord's Prayer;[8][9][10] the injunction to pray the Lord's prayer thrice daily was given in Didache 8, 2 f.,[11][12][13] which, in turn, was influenced by the Jewish practice of praying thrice daily found in the Old Testament, specifically in Psalm 55:17, which suggests "evening and morning and at noon", and Daniel 6:10, in which the prophet Daniel prays thrice a day.[11][12][14][15] The early Christians thus came to pray the Lord's Prayer at 9 am, 12 pm and 3 pm.[16]

Many Catholic Christian churches ring their bells thrice a day, at 6 am, 12 pm, and 6 pm to call the faithful to recite the Angelus, a prayer recited in honour of the Incarnation of God.[17][18]

Some Protestant Christian Churches ring church bells during the congregational recitation of the Lord's Prayer, after the sermon, in order to alert those who are unable to be present to "unite themselves in spirit with the congregation".[19][20]

In many historic Christian Churches, church bells are also rung on All Hallows' Eve,[21] as well as during the processions of Candlemas and Palm Sunday;[22] the only time of the Christian Year when church bells are not rung include Maundy Thursday through the Easter Vigil.[23] The Christian tradition of the ringing of church bells from a belltower is analogous to the Islamic tradition of the adhan from a minaret.[24][25]

Call to worship

Most Christian denominations ring church bells to call the faithful to worship, signalling the start of a mass or service of worship.[19][26]

In the United Kingdom predominantly in the Anglican church, there is a strong tradition of change ringing on full-circle tower bells for about half an hour before a service. This originated from the early 17th century when bell ringers found that swinging a bell through a large arc gave more control over the time between successive strikes of the clapper. This culminated in ringing bells through a full circle, which let ringers easily produce different striking sequences; known as changes.

Exorcism of demons

In Christianity, the ringing of church bells is traditionally believed to drive out demons and other unclean spirits.[2][27][4] Inscriptions on church bells relating to this purpose of church bells, as well as the purpose of serving as a call to prayer and worship, were customary, for example "the sound of this bell vanquishes tempests, repels demons, and summons men".[3] Some churches have several bells with the justification that "the more bells a church had, the more loudly they rang, and the greater the distance over which they could be heard, the less likely it was that evil forces would trouble the parish."[27]

Funeral and memorial ringing

The ringing of a church bell in the English tradition to announce a death is called a death knell. The pattern of striking depended on the person who had died; for example in the counties of Kent and Surrey in England it was customary to ring three times three strokes for a man and three times two for a woman, with a varying usage for children.[28] The age of the deceased was then rung out. In small settlements this could effectively identify who had just died.[29]

There were three occasions surrounding a death when bells could be rung. There was the "Passing Bell" to warn of impending death, the second the Death Knell to announce the death, and the last was the "Lych Bell", or "Corpse Bell" which was rung at the funeral as the procession approached the church.[29] This latter is known today as the Funeral toll.

A more modern tradition where there are full-circle bells is to use "half-muffles" when sounding one bell as a tolled bell, or all the bells in change-ringing. This means a leather muffle is placed on the clapper of each bell so that there is a loud "open" strike followed by a muffled strike, which has a very sonorous and mournful effect. The tradition in the United Kingdom is that bells are only fully muffled for the death of a sovereign. A slight variant on this rule occurred in 2015 when the bones of Richard III of England were interred in Leicester Cathedral 532 years after his death.[30]

Sanctus bells

The term "Sanctus bell" traditionally referred to a bell suspended in a bell-cot at the apex of the nave roof, over the chancel arch, or hung in the church tower, in medieval churches. This bell was rung at the singing of the Sanctus and again at the elevation of the consecrated elements, to indicate to those not present in the building that the moment of consecration had been reached. The practice and the term remain in common use in many Anglican churches.

Within the body of a church the function of a sanctus bell can also be performed by a small hand bell or set of such bells (called altar bells) rung shortly before the consecration of the bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ and again when the consecrated elements are shown to the people.[31] Sacring rings or "Gloria wheels" are commonly used in Catholic churches in Spain and its former colonies for this purpose.[32]

Orthodox Church

In the Eastern Orthodox Church there is a long and complex history of bell ringing, with particular bells being rung in particular ways to signify different parts of the divine services, Funeral tolls, etc. This custom is particularly sophisticated in the Russian Orthodox Church. Russian bells are usually stationary, and are sounded by pulling on a rope that is attached to the clapper so that it will strike the inside of the bell.

Clock chimes

Some churches have a clock chime which uses a turret clock to broadcast the time by striking the hours and sometimes the quarters. A well-known musical striking pattern is the Westminster Quarters. This is only done when the bells are stationary, and the clock mechanism actuates hammers striking on the outside of the sound-bows of the bells. In the cases of bells which are normally swung for other ringing, there is a manual lock-out mechanism which prevents the hammers from operating whilst the bells are being rung.

Warning of invasion

In World War II in Great Britain, all church bells were silenced, to ring only to inform of an invasion by enemy troops.[33] However this ban was lifted temporarily in 1942 and permanently in 1943 by order of Winston Churchill.

Design and ringing technique

Parts of a typical tower bell hung for swinging: 1. yoke, or headstock 2. canons, 3. crown, 4. shoulder, 5. waist, 6. sound bow, 7. lip, 8. mouth, 9. clapper, 10. bead line |

Christian church bells have the form of a cup-shaped cast metal resonator with a flared thickened rim, and a pivoted clapper hanging from its centre inside. It is usually mounted high in a bell tower on top of the church, so it can be heard by the surrounding community. The bell is suspended from a headstock which can swing on bearings. A rope is tied to a wheel or lever on the headstock, and hangs down to the bell ringer. To ring the bell, the ringer pulls on the rope, swinging the bell. The motion causes the clapper to strike the inside of the bell rim as it swings, thereby sounding the bell. Some bells have full-circle wheels, which is used to swing the bell through a larger arc, such as in the United Kingdom where full- circle ringing is practised.

Bells which are not swung are "chimed", which means they are struck by an external hammer, or by a rope attached to the internal clapper, which is the tradition in Russia.

Blessing of bells

In some churches, bells are often blessed before they are hung.

In the Roman Catholic Church the name Baptism of Bells has been given to the ceremonial blessing of church bells, at least in France, since the eleventh century. It is derived from the washing of the bell with holy water by the bishop, before he anoints it with the "oil of the infirm" without and with chrism within; a fuming censer is placed under it and the bishop prays that these sacramentals of the Church may, at the sound of the bell, put the demons to flight, protect from storms, and call the faithful to prayer.

History

Before the introduction of church bells into the Christian Church, different methods were used to call the worshippers: playing trumpets, hitting wooden planks, shouting, or using a courier.[34] In AD 604, Pope Sabinian officially sanctioned the usage of bells.[35][36] These tintinnabula were made from forged metal and did not have large dimensions.[34] Larger bells were made at the end of the 7th and during the 8th century by casting metal originating from Campania. The bells consequently took the name of campana and nola from the eponymous city in the region.[34] This would explain the apparently erroneous attribution of the origin of church bells to Paulinus of Nola in AD 400.[34][35][37] By the early Middle Ages, church bells became common in Europe.[38] They were first common in northern Europe, reflecting Celtic influence, especially that of Irish missionaries.[38] Before the use of church bells, Greek monasteries would ring a flat metal plate (see semantron) to announce services.[38] The signa and campanae used to announce services before Irish influence may have been flat plates like the semantron rather than bells.[38] The oldest surviving circle of bells in Great Britain is housed in St Lawrence Church, Ipswich.[39]

Controversies about noise

The sound of church bells is capable of causing noise that is damaging to human health, especially when it interrupts or prevents people from sleeping. A 2013 study from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich found that 'An estimated 2.5-3.5 percent of the population in the Canton of Zurich experiences at least one additional awakening per night due to church bell noise.' It concluded that 'The number of awakenings could be reduced by more than 99 percent by, for example, suspending church bell ringing between midnight and 06 h in the morning', or by 'about 75 percent (...) by reducing the sound-pressure levels of bells by 5 dB.'[40]

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, there have been many controversies and even lawsuits in 20th and early 21st century about church bell noise pollution experienced by nearby residents.[41] As of 2019, national legislation states that the sound of a church bell may not exceed 70 decibel between 7 am and 7 pm, no more than 65 decibel between 7 pm and 11 pm, and no more than 60 decibel between 11 pm and 7 am.[41]

The complaints are usually, but not always, raised by new local residents (or tourists who spend the night in the neighbourhood[42]) who are not used to the noise, especially at night and therefore cannot sleep (or sleep in on Sundays),[43][44][45] or during the day cannot hear the television, radio, telephone or understand each other in conversation.[42][44] Local residents who had been used to it for longer usually retort that the newcomers 'should have known this before they moved here' and that the ringing bells 'belong to the local tradition', which sometimes goes back more than a hundred years.[43][44][45][46][47] However, in some cases the local bell-playing tradition is not that old yet, or has allegedly recently increased in frequency or volume,[46][47][48] and it's also possible for residents who have already been living in the neighbourhood for decades to be or become bothered by it and start complaining.[44][45][48][49]

Some critics even wonder which function the church bells still serve in modern times[42][50] and why the right of churches to sound their bells so often prevails over the interests of people near it who do not need them to tell the time, do not go to that church (let alone adhere to the religion of that church), do not attend all the special ecclesiastical events such as weddings, funerals or award ceremonies of that church, and are not always pleased with the musical pieces coming from the steeples, but do experience noise pollution from it.[45][49][51] Medieval supplementary functions of church bells, such as warning for fires or other disasters, closing the city gates or collecting the tax have long fallen into disuse, and since the rise of watches in the 20th century and smartphones in the early 21st century their time-indicating function has also been largely rendered obsolete.[50]

- From the 1950s until 2011, a conflict lasting more than 50 years concerning the carillon of the St. Laurens Church in Weesp, which sounded throughout the night. The municipality invoked a 300-year-long tradition and the fact that most other inhabitants never complained, but the Court of Amsterdam ruled in favour of the complainants that the nocturnal bell-ringing was harmful to public health. When it turned out that it was impossible to diminish the sound, the city council decided on 23 June 2011 that the carillon would remain silent between 11 pm and 7 am.[52][53][54]

- In April and May 2005, resident J. Benedict brought his case to the Council of State against the college van burgemeester en wethouders of Amersfoort regarding the playing times and the volume of the Onze Lieve Vrouwetoren's church bells. A few years early, locals took their case to the National Ombudsman, which determined that the bell-playing fell within the jurisdiction of the Environmental Management Act (Wet milieubeheer) and thus required an environmental permit (milieuvergunning). The Council partially upheld the appeal: henceforth, there could be no bell-playing at night between 21:45 and 09:00, but the frequency by day complied to standards, and although the volume exceeded noise norms, it could not reasonably be reduced without sound distortion; therefore the chimes were maintained during the day because of their 'special historical and cultural significance'.[55][56]

- In December 2005, the college van burgemeester en wethouders of Nijmegen held a hearing with protesting local residents, and then decided the carillon of Saint Stephen's Church could henceforth only be sounded once per hour instead of every 15 minutes; the church had to obey its environmental permit that restricted the amount of noise it was allowed to produce.[47] Two locals and the Stephen's Church Foundation appealed, but the Council of State rejected their appeal in June 2006.[57]

- From 2006 until 2011, a legal battle raged between pastor Harm Schilder from the Margaret Mary Alacoque church in Tilburg, and nearby residents united in the action committee De Wakkere Luiden, who managed to get the municipality on their side. The Court of Breda eventually prohibited Schilder from sounding his chimes before 7:30 am, and forced him to keep the noise below 80 decibel.[58]

- 2017 saw several months of debate about the nocturnal bell-playing of the Dom Tower of Utrecht, which deprived several locals of sleep, and furthermore appeared to be illegal according to the municipality's own act to restrict noise from music at night. However, the college van burgemeester en wethouders claimed it was an 'error' and proposed to change the act to explicitly exclude the Dom Tower from it, supported by a large majority in the city council.[59]

- In Woerden, St. Bonaventura's Church's bells used to ring every 15 minutes, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week at a volume of 70 decibel, until a nearby resident complained that it kept him awake at night; the municipality then determined the church couldn't sound them after 11 pm, beginning in September 2019.[41]

- In September 2019 a resident, allegedly an expat, complained about the nocturnal bell-ringing of the Westertoren in Amsterdam in a letter to the college van burgemeester en wethouders; he suggested a 'break' between 0:00 and 6:00 so that people could sleep at night. The vast majority of other local residents was cross with the complainant, saying that he should go and live somewhere else, and that the sounds of the Westertoren carillon was part of the neighbourhood and their lives. A small group sympathised with the complaint, however. Over ten years earlier, other newcomers had also complained about the nightly noise, leading to the volume being toned down at night.[60]

Image gallery

Lullusglocke, cast in 1038, in monastery of Bad Hersfeld in Hesse, Germany

Lullusglocke, cast in 1038, in monastery of Bad Hersfeld in Hesse, Germany

.jpg.webp) Sigismund Bell in Kraków, Poland, cast in 1520 by Hans Beham

Sigismund Bell in Kraków, Poland, cast in 1520 by Hans Beham.JPG.webp) Pummerin in Stephansdom, Vienna

Pummerin in Stephansdom, Vienna Tsar Bell in Moscow, Russia, the heaviest existing bell in the world (over 196 tons)

Tsar Bell in Moscow, Russia, the heaviest existing bell in the world (over 196 tons) Belgian-made bell of St. Xavier's Church, Peyad, Trivandrum, Kerala, India

Belgian-made bell of St. Xavier's Church, Peyad, Trivandrum, Kerala, India Bell in the Cathedral Church of Saint Matthew, Dallas, Texas

Bell in the Cathedral Church of Saint Matthew, Dallas, Texas Bell in Cologne Cathedral

Bell in Cologne Cathedral Bell for San Miguel Mission

Bell for San Miguel Mission Ringing the bells at Ipatiev Monastery in Kostroma, Russia.

Ringing the bells at Ipatiev Monastery in Kostroma, Russia. Ring of eight bells in the tower of St Michael and All Angels' parish church, Blewbury, Oxfordshire

Ring of eight bells in the tower of St Michael and All Angels' parish church, Blewbury, Oxfordshire.jpg.webp) Bell in the Saint-Jacques church of Tournai

Bell in the Saint-Jacques church of Tournai.jpg.webp) Church bells of Ulm Minster seen from above (2019)

Church bells of Ulm Minster seen from above (2019)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Church bells. |

References

- Church Words: Origins and Meanings. Forward Movement. 1 August 1996. ISBN 9780880281720. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

There are two sorts of liturgical bells in the history of the Christian Church-church bells in spires or towers used to call the faithful to worship, and sanctuary bells used to call attention to the coming of Christ in the Holy Eucharist.

- Booth, Mark (11 February 2014). The Sacred History: How Angels, Mystics and Higher Intelligence Made Our World. Simon and Schuster. p. 274. ISBN 9781451698589.

Church bells would be rung to drive away demons.

- Cohen, I. Bernard (1990). Benjamin Franklin's Science. Harvard University Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780674066595.

The practice of ringing church bells to dissipate lightning storms and prevent their deleterious effects had a long tradition in Europe and had been a concomitant to the general belief in the diabolical agency manifested in storms. ... Typical inscriptions on church bells described their powr to "ward off lightning and malignant demons"; stated that "the sound of this bell vanquishes tempests, repels demons, and summons men," or exhorted it to "praise God, put to flight the coulds, affright the demons, and call the people"; or noted that "it is I who dissipate the thunders."

- Lewis, James R. (2001). Satanism Today. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576072929.

- Adato, Joseph; Judy, George. The Percussionist's Dictionary. Alfred Music. p. 11. ISBN 9781457493829.

- "What is the relationship between bells and the church? When and where did the tradition begin? Should bells ring in every church?". Coptic Orthodox Diocese of the Southern United States. 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Mary Cecil, 2nd Baroness Amherst of Hackney (1906). A Sketch of Egyptian History from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Methuen. p. 399.

Prayers 7 times a day are enjoined, and the most strict among the Copts recite one of more of the Psalms of David each time they pray. They always wash their hands and faces before devotions, and turn to the East.

- George Herbert Dryer (1897). History of the Christian Church. Curts & Jennings.

…every church-bell in Christendom to be tolled three times a day, and all Christians to repeat Pater Nosters (The Lord's Prayer)

- Joan Huyser-Honig (2006). "Uncovering the Blessing of Fixed-Hour Prayer". Calvin Institute of Christian Worship.

Early Christians prayed the Lord's Prayer three times a day. Medieval church bells called people to common prayer.

Missing or empty|url=(help) - "Church bells". Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod. 25 July 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Gerhard Kittel; Gerhard Friedrich (1972). Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, Volume 8. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 224. ISBN 9780802822505. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

The praying of the Lord's Prayer three times a day in Did., 8, 2 f. is connected with the Jewish practice --> 218, 3 ff.; II, 801, 16 ff.; the altering of other Jewish customs is demanded in the context.

- Roger T. Beckwith (2005). Calendar, Chronology, and Worship: Studies in Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity. Brill Publishers. p. 193. ISBN 9004146032. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

The Church had now two hours of prayer, observed individually on weekdays and corporately on Sundays – yet the Old Testament spoke of three daily hours of prayer, and the Church itself had been saying the Lord's Prayer three times a day.

- Matthew: A Shorter Commentary. Continuum International Publishing Group. 2005. ISBN 9780567082497. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

Moreover, the central portion of the Eighteen Benedictions, just like the Lord's Prayer, falls into two distinct parts (in the first half the petitions are for the individuals, in the second half for the nation); and early Christian tradition instructs believers to say the Lord's Prayer three times a day (Did. 8.3) while standing (Apost. const. 7.24), which precisely parallels what the rabbis demanded for the Eighteen Benedictions.

- James F White (1 September 2010). Introduction to Christian Worship 3rd Edition: Revised and Enlarged. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426722851. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

Late in the first century or early in the second, the Didache advised Christians to pray the Lord's prayer three times a day. Others sought disciplines in the Bible itself as ways to make the scriptural injunction to "pray without ceasing" (1 Thess. 5:17) practical. Psalm 55:17 suggested "evening and morning and at noon," and Daniel prayed three times a day (Dan. 6:10).

- Catechism Of The Catholic Church. Continuum International Publishing Group. 1999. ISBN 0-860-12324-3. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

Late in the first century or early in the second, the Didache advised Christians to pray the Lord's prayer three times a day. Others sought disciplines in the Bible itself as ways to make the scriptural injunction to "pray without ceasing" (1 Thess. 5:17) practical. Psalm 55:17 suggested "evening and morning and at noon," and Daniel prayed three times a day (Dan. 6:10).

- Beckwith, Roger T. (2005). Calendar, Chronology And Worship: Studies in Ancient Judaism And Early Christianity. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-14603-7.

So three minor hours of prayer were developed, at the third, sixth and ninth hours, which, as Dugmore points out, were ordinary divisions of the day for worldly affairs, and the Lord's Prayer was transferred to those hours.

- John P. Anderson (2009). Joyce's Finnegans Wake: The Curse of Kabbalah, Volume 2. Universal Publishers. ISBN 9781599429014. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

The Angelus is a Christian devotion in memory of the Incarnation. Its name is derived from the opening words, Angelus Domini nuntiavit Mariæ. It consists of three Biblical verses describing the mystery, recited as versicle and response, alternating with the salutation "Hail Mary!" and traditionally is recited in Catholic churches, convents and monasteries three times daily, 6:00 a.m., 12:00 noon and 6:00 p.m., accompanied by the ringing of the Angelus bell. Some High Church Anglican and Lutheran churches also use the devotion.

- The Anglican Service Book: A Traditional Language Adaptation of the 1979 Book of Common Prayer, Together with the Psalter Or Psalms of David and Additional Devotions. Good Shepherd Press. 1 September 1991. ISBN 9780962995507. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

The Angelus: In many churches the bell is run morning, noon, and evening in memory of the Incarnation of God, and the faithful say the following prayers, except during Eastertide, when the Regina coeli is said.

- The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Thought: Basilica-Chambers, Volume 2. Kessinger Publishing. 1952. p. 117.

The main use of bells has always been to announce the time of public worship. It is also a common Roman Catholic practise to ring the church bell at the consecration in the mass, as in some Protestant localities at the Lord's Prayer after the sermon, that those who are absent may unite themselves in spirit with the congregation.

- The Valley's Legends & Legacies IV. Quill Driver Books. 30 May 2002. p. 223. ISBN 9781884995217. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

At the end of the sermon, both bells began to ring and continued ringing through the Lord's Prayer.

- Bannatyne, Lesley (31 August 1998). Halloween. Pelican Publishing Company. p. 22. ISBN 9781455605538.

Priests in tiny Spanish villages still ring their church bells to remind parishioners to honor the dead on All Hallows Eve.

- Church Words: Origins and Meanings. Forward Movement. 1 August 1996. ISBN 9780880281720. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

It is also traditional that the church bells ring during the processions of Candlemas (the Feast of the Purification) and Palm Sunday.

- Church Words: Origins and Meanings. Forward Movement. 1 August 1996. ISBN 9780880281720. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

It is traditional that no bells be rung from the last service on Maundy Thursday until the Great Vigil of Easter.

- Church Words: Origins and Meanings. Psychology Press. 1 August 1996. ISBN 9780880281720. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

But even for Muslims who pray infrequently, the adhan marks the passage of time through the day (in much the same way as church bells do in many Christian communities) and serves as a constant reminder that they are living in a Muslim community.

- Islamic Beliefs, Practices, and Cultures. Marshal Cavendish. 1 September 2010. p. 77. ISBN 9780761479260. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

Muslims living in predominantly Islamic lands, however, have the benefit of the call to prayer (adhan). In the same way that much of the Christian world traditionally used bells to summon the faithful to church services, so the early Muslim community developed its own method of informing the community that the time for prayer had arrived.

- Church Words: Origins and Meanings. Forward Movement. 1 August 1996. ISBN 9780880281720. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

It became customary to ring the church bells to call the faithful to worship and on other important occasions, such as the death of a parishioner.

- Fanthorpe, Lionel; Fanthorpe, Patricia (1 October 2002). The World's Most Mysterious Objects. Dundurn. p. 100. ISBN 9781770707580.

- Stahlschmidt, J. C. L. (1887). The Church Bells of Kent: Their Inscriptions, Founders, Uses and Traditions. London: Elliot Stock. p. 126.

- H B Walters, The Church bells of England. published 1912 and republished 1977 by Oxford University Press. pp156-160

- Bob Triples, fully muffled bells on YouTube

- General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 150

- Herrera, Matthew D. (2005). Sanctus Bells. Their History and Use in the Catholic Church. Adoremus Bulletin. Retrieved on 2014-11-11.

- WW2 People's War - Recollections of a Wartime Childhood

- Buse, Adolf (1858). S. Paulin évêque de Nole et son siècle (350-450) (in French). Translated by Dancoisne, L. Paris: H. Casterman. pp. 415–418.

- Roger J. Smith (1997). "Church Bells". Sacred Heart Catholic Church and St. Yves Mission.

Bells came into use in our churches as early as the year 400, and their introduction is ascribed to Paulinus, bishop of Nola, a town of Campania, in Italy. Their use spread rapidly, as in those unsettled times the church-bell was useful not only for summoning the faithful to religious services, but also for giving an alarm when danger threatened. Their use was sanctioned in 604 by Pope Sabinian, and a ceremony for blessing them was established a little later. Very large bells, for church towers, were probably not in common use until the eleventh century.

- Henry Beauchamp Walters (1908). Church Bells. A. R. Mowbray & Company. p. 4.

- Kathy Luty; David Philippart (1997). Clip Notes for Church Bulletins - Volume 1.

The first known use of bells in churches was by a bishop named Paulinus in the year 400.

- "Bells." Catholic Encyclopedia. read online

- Worthington, Mark (10 September 2009). "Oldest ring of bells played again". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- Omlin, S.; Brink, M. (October 2013). "Awakening effects of church bell noise: geographical extrapolation of the results of a polysomnographic field study 1". Noise & Health. Medknow Publications. 15 (66): 332–41. doi:10.4103/1463-1741.116582. PMID 23955130.

- "Kerkklok op mute". RTL Nieuws. 2 August 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Kerkklok beiert hotelgasten wakker". Hart van Nederland. 12 May 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Patrick Meershoek (18 September 2019). "Moet dat nou, dat gebimbambeier van de Westerkerk?". Het Parool. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Omwonenden worden gek van kerkklokken Oostvoorne". RTV Rijnmond. 11 March 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Niels Dekker (26 July 2015). "Klokgelui van de kerken, een zegen of een vloek?". Algemeen Dagblad. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Geraldina Metselaar (25 February 2018). "Geluid van carillon drijft omwonende tot wanhoop". Algemeen Dagblad. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Arjen Schreuder (6 January 2006). "Milieuregels gelden ook voor carillons". NRC Handelsblad. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Moet de Domtoren de hele nacht blijven luiden?". De Utrechtse Internet Courant. 14 July 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

Onno Nugteren has been living in the Korte Nieuwstraat for 24 years already, and said he managed to become only partially accustomed to the sound of the Dom Tower of Utrecht. (...) Together with his neighbour Peter Oostveen he tries to get the municipality to keep the Dom Tower silent from midnight until 8 am. (...) "The argument that [the municipality makes] is that het carillon has always been sounding every 15 minutes. But that is not true at all; not until the 1990s a hobbyist came along and made up the idea that the carillon should be played four times per hour.

- Gert-Jan Buijs (26 March 2018). "Bimbambom. Leuk, zo'n kerkklok. Maar wat als je d'r niet tegen kan?". Brabants Dagblad. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

Then you shouldn't go and live near a church? I've been living in Drunen all my life. I've never lived anywhere further away from the church.

- Kris Derks (8 July 2011). "Waarom luiden klokken eigenlijk nog?". NRC Handelsblad. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Sandra Don (20 July 2016). "Schiedammer: Paal en perk stellen aan luiden kerkklok". Algemeen Dagblad. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Kwestie carillon Weesp nu zelfs voor meervoudige kamer". NH Nieuws. 9 March 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Annejet Lamme (13 July 2011). "Kerkklokken aan banden". Wieringa Advocaten. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Carillon Weesp gaat 's nachts uit". Weesper Nieuws. 23 June 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Raad van State moet speeltijden carillon Amersfoort bepalen". Reformatorisch Dagblad. 13 April 2005. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- Marlies Jongma (4 May 2005). "Oprichtingsvergunning krachtens de Wet milieubeheer voor een klokkentoren met carillon. (Amersfoort)" (PDF). Jurisprudentie Tijdschrift. Raad van State. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- "Uitspraak 200600626/1". Raad van State. 28 June 2006. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Pastoor mag luide kerkklok niet vroeg luiden". Trouw. 20 October 2010. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Maarten Venderbosch (1 September 2017). "Domcarillon blijft spelen in de nacht". Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Martin Kuiper (19 September 2019). "Moeten de klokken van de Westertoren 's nachts zwijgen?". NRC Handelsblad. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

External links

- Animation of English Full-circle church bell ringing

- Video of English full circle-ringing, 8 bells half muffled and one bell tolling

- Video of English full circle-ringing, 8 bells ringing "open"

- Sound of Bells - An Investigation into their tuning

- Research and Identification of Valuable Bells of the Historic and Culture Heritage of Bulgaria and Development of Audio and Video Archive with Advanced Technologies

- Bell-Ringing Central

- Old archive image of church bells in Chatham, Kent, England, ca.1900

- All Saints Bell Tower