ExxonMobil

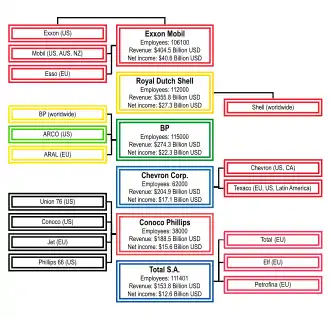

Exxon Mobil Corporation, stylized as ExxonMobil, is an American multinational oil and gas corporation headquartered in Irving, Texas. It is the largest direct descendant of John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil,[2] and was formed on November 30, 1999 by the merger of Exxon (formerly the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey) and Mobil (formerly the Standard Oil Company of New York). ExxonMobil's primary brands are Exxon, Mobil, Esso, and ExxonMobil Chemical.[3] ExxonMobil is incorporated in New Jersey.[4]

ExxonMobil Global Headquarters | |

| Type | Public |

|---|---|

| ISIN | US30231G1022 |

| Industry | Energy: Oil and gas |

| Predecessor | |

| Founded | November 30, 1999 |

| Founder | Ultimately descended from Standard Oil founded by John D. Rockefeller |

| Headquarters | , U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Darren Woods (chairman & CEO) |

| Products | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 74,900[1] (2019) |

| Subsidiaries | |

| Website | corporate |

One of the world's largest companies by revenue, ExxonMobil from 1996 to 2017 varied from the first to sixth largest publicly traded company by market capitalization.[5][6] The company was ranked third globally in the Forbes Global 2000 list in 2016.[7] ExxonMobil was the tenth most profitable company in the Fortune 500 in 2017.[8] As of 2018, the company ranked second in the Fortune 500 rankings of the largest United States corporations by total revenue.[9] Approximately 55.56% of the company's shares are held by institutions. As of March 2019, ExxonMobil's largest shareholders include The Vanguard Group (8.15%), BlackRock (6.61%), and State Street Corporation (4.83%).

ExxonMobil is one of the largest of the world's Big Oil companies.[9] As of 2007, it had daily production of 3.921 million BOE (barrels of oil equivalent); but significantly smaller than a number of national companies. In 2008, this was approximately 3% of world production, which is less than several of the largest state-owned petroleum companies.[10] When ranked by oil and gas reserves, it is 14th in the world—with less than 1% of the total.[11][12] ExxonMobil's reserves were 20 billion BOE at the end of 2016 and the 2007 rates of production were expected to last more than 14 years.[13] With 37 oil refineries in 21 countries constituting a combined daily refining capacity of 6.3 million barrels (1,000,000 m3), ExxonMobil is the seventh largest refiner in the world,[14][15][16] a title that was also associated with Standard Oil since its incorporation in 1870.[2]

ExxonMobil had been criticized for its slow response to cleanup efforts after the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska,[17] considered to be one of the world's worst oil spills[18] in terms of damage to the environment. ExxonMobil has a history of lobbying for climate change denial and against the scientific consensus that global warming is caused by the burning of fossil fuels. However, the company says that it has taken steps to minimise the environmental impact of its operations.[19] The company has also been the target of accusations of improperly dealing with human rights issues, influence on American foreign policy, and its impact on the future of nations.[20]

History

ExxonMobil was formed in 1999 by the merger of two major oil companies, Exxon and Mobil.[21]

1870 to 1911

Both Exxon and Mobil were descendants of Standard Oil, established by John D. Rockefeller and partners in 1870 as the Standard Oil Company of Ohio. In 1882, it together with its affiliated companies was incorporated as the Standard Oil Trust with Standard Oil Company of New Jersey and Standard Oil Company of New York as its largest companies.[22] The Anglo-American Oil Company was established in the United Kingdom in 1888.[23] In 1890, Standard Oil, together with local ship merchants in Bremen established Deutsch-Amerikanische Petroleum Gesellschaft (later: Esso A.G.).[24][25] In 1891, a sale branch for the Netherlands and Belgium, American Petroleum Company, was established in Rotterdam.[26] At the same year, a sale branch for Italy, Società Italo Americana pel Petrolio, was established in Venice.[27]

The Standard Oil Trust was dissolved under the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1892; however, it reemerged as the Standard Oil Interests.[22] In 1893, the Chinese and the whole Asian kerosene market was assigned to Standard Oil Company of New York in order to improve trade with the Asian counterparts.[28] In 1898, Standard Oil of New Jersey acquired controlling stake in Imperial Oil of Canada.[24] In 1899, Standard Oil Company of New Jersey became the holding company for the Standard Oil Interests.[22] The anti-monopoly proceedings against the Standard Oil were launched in 1898.[22] The reputation of Standard Oil in the public eye suffered badly after publication of Ida M. Tarbell's classic exposé The History of the Standard Oil Co. in 1904, leading to a growing outcry for the government to take action against the company. By 1911, with public outcry at a climax, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States that Standard Oil must be dissolved and split into 34 companies. Two of these companies were Jersey Standard ("Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey"), which eventually became Exxon, and Socony ("Standard Oil Co. of New York"), which eventually became Mobil.[29]

1911 to 1950

Over the next few decades, Jersey Standard and Socony grew significantly. John Duston Archbold was the first president of Jersey Standard. Archbold was followed by Walter C. Teagle in 1917, who made it the largest oil company in the world.[29] In 1919, Jersey Standard acquired a 50% share in Humble Oil & Refining Co., a Texas oil producer.[22] In 1920, it was listed on the New York Stock Exchange.[29] In the following years it acquired or established Tropical Oil Company of Colombia (1920), Standard Oil Company of Venezuela (1921), and Creole Petroleum Company of Venezuela (1928).[24]

Henry Clay Folger was head of Socony until 1923, when he was succeeded by Herbert L. Pratt. The growing automotive market inspired the product trademark Mobiloil, registered by Socony in 1920. After dissolution of Standard Oil, Socony had refining and marketing assets but no production activities. For this reason, Socony purchased a 45% interest in Magnolia Petroleum Co., a major refiner, marketer and pipeline transporter, in 1918. In 1925, Magnolia became wholly owned by Socony. In 1926, Socony purchased General Petroleum Corporation of California.[22][29] In 1928, Socony joined the Turkish Petroleum Company (Iraq Petroleum Company).[29] In 1931, Socony merged with Vacuum Oil Company, an industry pioneer dating back to 1866, to form Socony-Vacuum.[22][29][30]

In the Asia-Pacific region, Jersey Standard has established through its Dutch subsidiary an exploration and production company Nederlandsche Koloniale Petroleum Maatschappij in 1912. In 1922, it found oil in Indonesia and in 1927, it built a refinery in Sumatra.[31] It had oil production and refineries but no marketing network. Socony-Vacuum had Asian marketing outlets supplied remotely from California. In 1933, Jersey Standard and Socony-Vacuum merged their interests in the Asia-Pacific region into a 50–50 joint venture. Standard Vacuum Oil Company, or "Stanvac," operated in 50 countries, from East Africa to New Zealand, before it was dissolved in 1962.[22]

In 1924, Jersey Standard and General Motors pooled its tetraethyllead-related patents and established the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation.[32] In 1927, Jersey Standard signed a 25-years cooperation agreement with IG Farben for the coal hydrogenation research in the United States. Jersey Standard assumed this cooperation to be beneficial as it believed the United States oil reserves to be exhausted in the near future and that the coal hydrogenation would give an access for producing synthetic fuels. It erected synthetic fuel plants in Bayway, Baton Rouge, and Baytown (unfinished). The interest in hydrogenation evaporated after discovery of the East Texas Oil Field.[33] As a part of the cooperation between Jersey Standard and IG Farben, a joint company, Standard I.G. Company, was established with Jersey Standard having a stake of 80%. IG Farben transferred rights to the hydrogenation process outside of Germany to the joint venture in exchange of $35 million stake of Jersey Standard shares.[34] In 1930, the joint company established Hydro Patents Company to license the hydrogenation process in the United States.[35] The agreement with IG Farben gave to Jersey Standard access to patents related to polyisobutylene which assist Jersey Standard to advance in isobutolene polymerization and to produce the first butyl rubber in 1937.[29][36][37] As the agreement with IG Farben gave to the German company a veto right of licensing chemical industry patents in the United States, including patent for butyl rubber, Jersey Standard was accused of treason by senator Harry S. Truman.[38] In 1941, it opened the first commercial synthetic toluene plant.[29]

In 1932, Jersey Standard acquired foreign assets of the Pan American Petroleum and Transport Company. In 1937, its assets in Bolivia were nationalized, followed by the nationalization of its assets in Mexico in 1938.[29]

Since the 1911 Standard Oil Trust breakup, Jersey Standard used the trademark Esso, a phonetic pronunciation of the initials "S" and "O" in the name Standard Oil,[2] as one of its primary brand names.[39] However, several of the other Standard Oil spinoffs objected to the use of that name in their territories, and successfully got the U.S. federal courts in the 1930s to ban the Esso brand in those states.[40] In those territories where the ban was in force, Jersey Standard instead marketed its products under the Enco or Humble names.[39]

In 1935, Socony Vacuum Oil opened the huge Mammoth Oil Port on Staten Island, which had a capacity of handling a quarter of a billion gallons of petroleum products a year and could transship oil from ocean-going tankers and river barges.[41] In 1940, Socony-Vacuum purchased the Gilmore Oil Company of California, which in 1945 was merged with another subsidiary, General Petroleum Corporation.[42] In 1947, Jersey Standard and Royal Dutch Shell formed the joint venture Nederlandse Aardolie Maatschappij BV for oil and gas exploration and production in the Netherlands.[43] In 1948, Jersey Standard and Socony-Vacuum acquired interests in the Arab-American Oil Company (Aramco).[22][44]

1950 to 1972

In 1955, Socony-Vacuum became Socony Mobil Oil Company. In 1959, Magnolia Petroleum Company, General Petroleum Corporation, and Mobil Producing Company were merged to form the Mobil Oil Company, a wholly owned subsidiary of Socony Mobil. In 1966, Socony Mobil Oil Company became the Mobil Oil Corporation.[22]

Humble Oil became a wholly owned subsidiary of Jersey Standard and was reorganized into the United States marketing division of Jersey Standard in 1959. In 1967, Humble Oil purchased all remaining Signal stations from Standard Oil Company of California (Chevron) In 1969, Humble Oil opened a new refinery in Benicia, California.

In Libya, Jersey Standard made its first major oil discovery in 1959.[22]

Mobil Chemical Company was established in 1960 and Exxon Chemical Company (first named Enjay Chemicals) in 1965.[22]

In 1965, Jersey Standard started to acquire coal assets through its affiliate Carter Oil (later renamed Exxon Coal, U.S.A.). For managing the Midwest and Eastern coal assets in the United States, the Monterey Coal Company was established in 1969.[45] Carter Oil focused on the developing synthetic fuels from coal.[45] In 1966, it started to develop the coal liquefaction process called the Exxon Donor Solvent Process. In April 1980, Exxon opened a 250-ton-per-day pilot plant in Baytown, Texas. The plant was closed and dismantled in 1982.[46]

In 1967, Mobil acquired a 28% strategic stake in the German fuel chain Aral.[47]

In late 1960s Jersey Standard task force was looking for projects 30 years in the future.[48][49] In April 1973, Exxon founded Solar Power Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary for manufacturing of terrestrial photovoltaic cells.[50] After 1980s oil glut Exxon's internal report projected that solar would not become viable until 2012 or 2013.[51] Consequently, Exxon sold Solar Power Corporation in 1984.[50] In 1974–1994, also Mobil developed solar energy through Mobil Tyco Solar Energy Corporation, its joint venture with Tyco Laboratories.[50][52]

In late 1960s, Jersey Standard entered into the nuclear industry. In 1969, it created a subsidiary, Jersey Nuclear Company (later: Exxon Nuclear Company), for manufacturing and marketing of uranium fuel, which was to be fabricated from uranium concentrates mined by the mineral department of Humble Oil (later: Exxon Minerals Company).[53] In 1970, Jersey Nuclear opened a nuclear fuel manufacturing facility, now owned by Framatome, in Richland, Washington.[54] In 1986, Exxon Nuclear was sold to Kraftwerk Union, a nuclear arm of Siemens.[55][56] The company started surface mining of uranium ore in Converse County, Wyoming, in 1970, solution mining in 1972, and underground mining in 1977. Uranium ore processing started in 1972. The facility was closed in 1984.[57] In 1973, Exxon acquired the Ray Point uranium ore processing facility which was shortly afterwards decommissioned.[58]

1972 to 1998

In 1972, Exxon was unveiled as the new, unified brand name for all former Enco and Esso outlets. At the same time, the company changed its corporate name from Standard Oil of New Jersey to Exxon Corporation, and Humble Oil became Exxon Company, U.S.A.[22] The rebranding came after successful test-marketing of the Exxon name, under two experimental logos, in the fall and winter of 1971–72. Along with the new name, Exxon settled on a rectangular logo using red lettering and blue trim on a white background, similar to the familiar color scheme on the old Enco and Esso logos. Exxon replaced the Esso, Enco, and Humble brands in the United States on January 1, 1973.

Due to the oil embargo of 1973, Exxon and Mobil began to expand their exploration and production into the North Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, Africa, and Asia. Mobil diversified its activities into retail sale and packaging by acquiring the parent company of Montgomery Ward and Container Corporation of America.[22]

In 1976, Exxon, through its subsidiary Intercor, entered into partnership with Colombian state owned company Carbocol to start coal mining in Cerrejón.[59] In 1980, Exxon merged its assets in the mineral industry into newly established Exxon Minerals (later ExxonMobil Coal and Minerals).[60] At the same year, Exxon entered into the oil shale industry by buying a 60% stake in the Colony Shale Oil Project in Colorado, United States,[61] and 50% stake in the Rundle oil shale deposit in Queensland, Australia.[62] On May 2, 1982, Exxon announced the termination of the Colony Shale Oil Project because of low oil-prices and increased expenses.[29][61]

Mobil moved its headquarters from New York to Fairfax County, Virginia, in 1987.[63] Exxon sold the Exxon Building (1251 Avenue of the Americas), its former headquarters in Rockefeller Center, to a unit of Mitsui Real Estate Development Co. Ltd. in 1986 for $610 million, and in 1989, moved its headquarters from Manhattan, New York City to the Las Colinas area of Irving, Texas. John Walsh, president of Exxon subsidiary Friendswood Development Company, stated that Exxon left New York because the costs were too high.[64]

On March 24, 1989, the Exxon Valdez oil tanker struck Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound, Alaska and spilled more than 11 million US gallons (42,000 m3) of crude oil. The Exxon Valdez oil spill was the second largest in U.S. history, and in the aftermath of the Exxon Valdez incident, the U.S. Congress passed the Oil Pollution Act of 1990. An initial award of US$5 billion punitive was reduced to $507.5 million by the US Supreme Court in June 2008,[65] and distributions of this award have commenced.

In 1994, Mobil established a subsidiary MEGAS (Mobil European Gas), which became responsible for its Mobil's natural gas operations in Europe.[66] In 1996, Mobil and British Petroleum merged their European refining and marketing of fuels and lubricants businesses. Mobil had 30% stake in fuels and 51% stake in lubricants businesses.[67]

In 1996, Exxon entered into the Russian market by signing a production sharing agreement on the Sakhalin-I project.[68]

1998 to 2000

In 1998, Exxon and Mobil signed a US$73.7 billion merger agreement forming a new company called Exxon Mobil Corp. (ExxonMobil), the largest oil company and the third-largest company in the world. This was the largest corporate merger at that time. At the time of the merger, Exxon was the world's largest energy company while Mobil was the second-largest oil and gas company in the United States. The merger announcement followed shortly after the merge of British Petroleum and Amoco, which was the largest industrial merger at the time.[69] Formally, Mobil was bought by Exxon. Mobil's shareholders received 1.32 Exxon's share for each Mobil's share. As a result, the former Mobil's shareholders receives about 30% in the merged company while the stake of former Exxon's shareholders was about 70%. The head of Exxon Lee Raymond remained the chairman and chief executive of the new company and Mobil chief executive Lucio Noto became vice-chairman.[69] The merger of Exxon and Mobil was unique in American history because it reunited the two largest companies of the Standard Oil trust.[70]

The merger was approved by the European Commission on September 29, 1999, and by the United States Federal Trade Commission on November 30, 1999.[71][72] As a condition for the Exxon and Mobil merger, the European Commission ordered to dissolve the Mobil's partnership with BP, as also to sell its stake in Aral.[47] As a result, BP acquired all fuels assets, two base oil plants, and a substantial part of the joint venture's finished lubricants business, while ExxonMobil acquired other base oil plants and a part of the finished lubricants business.[73] The stake in Aral was sold to Vega Oel, later acquired by BP.[47] The European Commission also demanded divesting of Mobil's MEGAS and Exxon's 25% stake in the German gas transmission company Thyssengas.[74] MEGAS was acquired by Duke Energy and the stake in Thyssengas was acquired by RWE.[75] The company also divested Exxon's aviation fuel business to BP and Mobil's certain pipeline capacity servicing Gatwick Airport.[76] The Federal Trade Commission required to sell 2,431 gas stations in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic (1,740), California (360), Texas (319), and Guam (12). In addition, ExxonMobil should sell its Benicia Refinery in California, terminal operations in Boston, the Washington, D.C. area and Guam, interest in the Colonial pipeline, Mobil's interest in the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, Exxon's jet turbine oil business, and give-up the option to buy Tosco Corporation gas stations.[77][78] The Benicia Refinery and 340 Exxon-branded stations in California were bought by Valero Energy Corporation in 2000.[79]

2000 to present

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, ExxonMobil has received a lot of criticism along with BP, China National Petroleum Corporation, Royal Dutch Shell, and Lukoil, for increasing oil production facilities in the Rumaila oil field and West Qurna Field following the Iraqi government's lack of power and instability resulting from the Iraq War. ExxonMobil alone produces 2,325,000 bpd or $967,432,500 per year of gross revenue in Iraq to maintain low prices. This practice is considered to be beneficial to the big oil consumer countries and allows Exxon to produce higher profit crude oil products such as plastic, fertilizer, medication, lubricant, and clothing.

In 2002, the company sold its stake in the Cerrejón coal mine in Colombia, and copper-mining business in Chile.[59][80] At the same time, it renewed its interest in oil shale by developing the ExxonMobil Electrofrac in-situ extraction process. In 2014, the Bureau of Land Management approved their research and development project in Rio Blanco County, Colorado.[81][82] However, in November 2015 the company relinquished its federal research, development and demonstration lease.[83] In 2009, ExxonMobil phased-out coal mining by selling its last operational coal mine in the United States.[84]

In 2008, ExxonMobil started to phase-out from the United States direct-served retail market by selling its service stations. The usage of Exxon and Mobil brands was franchised to the new owners.[85]

In 2010, ExxonMobil bought XTO Energy, the company focused on development and production of unconventional resources.[86]

In 2011, ExxonMobil started a strategic cooperation with Russian oil company Rosneft to develop the East-Prinovozemelsky field in the Kara Sea and the Tuapse field in the Black Sea.[87] In 2012, ExxonMobil concluded an agreement with Rosneft to assess possibilities to produce tight oil from Bazhenov and Achimov formations in Western Siberia.[88][89] In 2018, due to international sanctions imposed against Russia and Rosneft, ExxonMobil announces that it will end these joint ventures with Rosneft, but will continue the Sakhalin-I project.[90] The company estimates it would cost about $200 million after tax.[91][92]

In 2012, ExxonMobil started a coalbed methane development in Australia, but withdrew from the project in 2014.[93]

In 2012, ExxonMobil confirmed a deal for production and exploration activities in the Kurdistan region of Iraq.[94]

In November 2013, ExxonMobil agreed to sell its majority stakes in a Hong Kong-based utility and power storage firm, Castle Peak Co Ltd, for a total of $3.4 billion, to CLP Holdings.[95]

In 2014, ExxonMobil had two "non-monetary" asset swap deals with LINN Energy LLC. In these transactions, ExxonMobil gave to LINN interests in the South Belridge and Hugoton gas fields in the exchange of assets in the Permian Basin in Texas and the Delaware Basin in New Mexico.[96]

On October 9, 2014, the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes awarded ExxonMobil $1.6 billion in the case the company had brought against the Venezuelan government. ExxonMobil alleged that the Venezuelan government illegally expropriated its Venezuelan assets in 2007 and paid unfair compensation.[97]

In September 2016, the Securities and Exchange Commission contacted ExxonMobil, questioning why (unlike some other companies[98][99]) they had not yet started writing down the value of their oil reserves, given that much may have to remain in the ground to comply with future climate change legislation.[100][101][102][103] Mark Carney has expressed concerns about the industry's "stranded assets". In October 2016, ExxonMobil conceded it may need to declare a lower value for its in-ground oil, and that it might write down about one-fifth of its reserves.[104][105]

Also in September 2016, ExxonMobil successfully asked a U.S. federal court to lift the trademark injunction that banned it from using the Esso brand in various U.S. states. By this time, as a result of numerous mergers and rebranding, the remaining Standard Oil companies that previously objected to the Esso name had been acquired by BP. ExxonMobil cited trademark surveys in which there was no longer possible confusion with the Esso name as it was more than seven decades before. BP also had no objection to lifting the ban.[40] ExxonMobil did not specify whether they would now open new stations in the U.S. under the Esso name; they were primarily concerned about the additional expenses of having separate marketing, letterheads, packaging, and other materials that omit "Esso".[106]

On December 13, 2016, the CEO of ExxonMobil, Rex Tillerson, was nominated as Secretary of State by President-elect Donald Trump.[107]

In January 2017, Federal climate investigations of ExxonMobil were considered less likely under the new Trump administration.[108]

On January 9, 2017, it was revealed that Infineum, a joint venture of ExxonMobil and Royal Dutch Shell headquartered in England, conducted business with Iran, Syria, and Sudan while those states were under US sanctions. ExxonMobil representatives said that because Infineum was based in Europe and the transactions did not involve any U.S. employees, this did not violate the sanctions.[109]

In April 2017, Donald Trump's administration denied a request from ExxonMobil to allow it to resume oil drilling in Russia. Representative Adam Schiff (D-California) said that the "Treasury Department should reject any waiver from sanctions which would allow Exxon Mobil or any other company to resume business with prohibited Russian entities."[110]

In July 2017, ExxonMobil filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration challenging the finding that the company violated sanctions imposed on Russia. William Holbrook, a company spokesman, said that the ExxonMobil had followed "clear guidance from the White House and Treasury Department when its representatives signed [in May 2014] documents involving ongoing oil and gas activities in Russia with Rosneft".[111]

In June 2019, following Washington D.C.'s increased sanctions on Iran, a rocket landed near the residential headquarters of ExxonMobil,[112] Royal Dutch Shell, and ENI SpA. It came after two separate attacks on United States Military bases in Iraq and one week after two oil tankers being hit by a 'flying object' in the Gulf of Oman. The U.S. Navy's investigation has led to reasonable suspicion to believe Tehran's connection to the attacks.

In October 2020, ExxonMobil announced that it will cut over 1,600 jobs in Europe as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the company, the job cuts are necessary in order to produce cost cuts and they will be implemented by the end of 2021. The number of job cuts represents one-tenth of the company's workforce, which was estimated at nearly 75,000 by the end of 2019.[113]

Operations

ExxonMobil is the largest non-government owned company in the energy industry and produces about 3% of the world's oil and about 2% of the world's energy.[114]

ExxonMobil is organized functionally into a number of global operating divisions. These divisions are grouped into three categories for reference purposes, though the company also has several ancillary divisions, such as Coal & Minerals, which are stand alone. It also owns hundreds of smaller subsidiaries such as Imperial Oil Limited (69.6% ownership) in Canada, and SeaRiver Maritime, a petroleum shipping company.[115]

- Upstream (oil exploration, extraction, shipping, and wholesale operations) based in Houston

- Downstream (marketing, refining, and retail operations) based in Houston

- Chemical division based in Houston

Upstream

The upstream division makes up the majority of ExxonMobil's revenue, accounting for approximately 70% of the total.[116] In 2014, the company had 25.3 billion barrels (4.02×109 m3) of oil-equivalent reserves.[117] In 2013, its reserves replacement ratio was 103%.[117]

In the United States, ExxonMobil's petroleum exploration and production activities are concentrated in the Permian Basin, Bakken Formation, Woodford Shale, Caney Shale, and the Gulf of Mexico. In addition, ExxonMobil has several gas developments in the regions of Marcellus Shale, Utica Shale, Haynesville Shale, Barnett Shale, and Fayetteville Shale. All natural gas activities are conducted by its subsidiary, XTO Energy. As of December 31, 2014, ExxonMobil owned 14.6 million acres (59,000 km2) in the United States, of which 1.7 million acres (6,900 km2) were offshore, 1.5 million acres (6,100 km2) of which were in the Gulf of Mexico.[118] In California, it has a joint venture called Aera Energy LLC with Shell Oil. In Canada, the company holds 5.4 million acres (22,000 km2), including 1 million acres (4,000 km2) offshore and 0.7 million acres (2,800 km2) of the Kearl Oil Sands Project.[118]

In Argentina, ExxonMobil holds 0.9 million acres (3,600 km2), Germany 4.9 million acres (20,000 km2), in the Netherlands ExxonMobil owns 1.5 million acres (6,100 km2), in Norway it owns 0.4 million acres (1,600 km2) offshore, and the United Kingdom 0.6 million acres (2,400 km2) offshore. In Africa, upstream operations are concentrated in Angola where it owns 0.4 million acres (1,600 km2) offshore, Chad where it owns 46,000 acres (19,000 ha), Equatorial Guinea where it owns 0.1 million acres (400 km2) offshore, and Nigeria where it owns 0.8 million acres (3,200 km2) offshore.[118] In addition, Exxon Mobil plans to start exploration activities off the coast of Liberia and the Ivory Coast.[119][120] In the past, ExxonMobil had exploration activities in Madagascar, however these operations were ended due to unsatisfactory results.[121]

In Asia, it holds 9,000 acres (3,600 ha) in Azerbaijan, 1.7 million acres (6,900 km2) in Indonesia, of which 1.3 million acres (5,300 km2) are offshore, 0.7 million acres (2,800 km2) in Iraq, 0.3 million acres (1,200 km2) in Kazakhstan, 0.2 million acres (810 km2) in Malaysia, 65,000 acres (26,000 ha) in Qatar, 10,000 acres (4,000 ha) in Yemen, 21,000 acres (8,500 ha) in Thailand, and 81,000 acres (33,000 ha) in the United Arab Emirates.[118]

In Russia, ExxonMobil holds 85,000 acres (34,000 ha) in the Sakhalin-I project. Together with Rosneft, it has developed 63.6 million acres (257,000 km2) in Russia, including the East-Prinovozemelsky field. In Australia, ExxonMobil held 1.7 million acres (6,900 km2), including 1.6 million acres (6,500 km2) offshore. It also operates the Longford Gas Conditioning Plant, and participates in the development of Gorgon LNG project. In Papua New Guinea, it holds 1.1 million acres (4,500 km2), including the PNG Gas project.[118]

Midstream

As of 2019, the company has joint ventures with pipelines to transport its upstream production, such as the Wink to Webster pipeline and the Double E pipeline (for which it has the option to purchase 50%[122]) to transport Permian Basin natural gas.[123]

Downstream

ExxonMobil markets products around the world under the brands of Exxon, Mobil, and Esso. Mobil is ExxonMobil's primary retail gasoline brand in California, Florida, New York, New England, the Great Lakes, and the Midwest. Exxon is the primary brand in the rest of the United States, with the highest concentration of retail outlets located in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Texas (shared with Mobil), and in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern states. Esso is ExxonMobil's primary gasoline brand worldwide except in Australia, Guam, Mexico, Nigeria, and New Zealand, where the Mobil brand is used exclusively. In Canada (from 2017), Colombia, Egypt, and formerly Japan (now switched to ENEOS from 2019) and Malaysia (now switched to Petron from 2013), both the Esso and Mobil brands are used. Both Esso and Mobil brands are applied to each Esso stations, in Hong Kong and Singapore since 2006.

In Japan, ExxonMobil has a 22% stake in TonenGeneral Sekiyu K.K., a refining company.[124][125]

Chemicals

ExxonMobil Chemical is a petrochemical company that was created by merging Exxon's and Mobil's chemical industries. Its principal products includes basic olefins and aromatics, ethylene glycol, polyethylene, and polypropylene along with speciality lines such as elastomers, plasticizers, solvents, process fluids, oxo alcohols and adhesive resins. The company also produces synthetic lubricant base stocks as well as lubricant additives, propylene packaging films and catalysts. The company was an industry leader in metallocene catalyst technology to make unique polymers with improved performance. ExxonMobil is the largest producer of butyl rubber.[126]

Infineum, a joint venture with Royal Dutch Shell, is manufacturing and marketing crankcase lubricant additives, fuel additives, and specialty lubricant additives, as well as automatic transmission fluids, gear oils, and industrial oils.[127]

Clean technology research

ExxonMobil conducts research on clean energy technologies, including algae biofuels, biodiesel made from agricultural waste, carbonate fuel cells, and refining crude oil into plastic by using a membrane and osmosis instead of heat.[128] However, it is unlikely the company will commercialize these projects before 2030.[128]

Corporate affairs

Financial data

According to Fortune Global 500, ExxonMobil was the second largest company, second largest publicly held corporation, and the largest oil company in the United States by 2017 revenue.[9] For the fiscal year 2019, ExxonMobil reported earnings of US$14.3 billion, with an annual revenue of US$264.938 billion, a decline of 8.7% over the previous fiscal cycle.

| Year | Revenue (mln. US$) |

Net income (mln. US$) |

Total assets (mln. US$) |

Price per share (US$) |

Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008[129] | 477,359 | 45,220 | 228,052 | 82.68 | 79,900 |

| 2009[129] | 310,586 | 19,280 | 233,323 | 70.95 | 80,700 |

| 2010[130] | 383,221 | 30,460 | 302,510 | 64.99 | 83,600 |

| 2011[131] | 486,429 | 41,060 | 331,052 | 79.71 | 82,100 |

| 2012[132] | 480,681 | 44,880 | 333,795 | 86.53 | 76,900 |

| 2013[133] | 438,255 | 32,580 | 346,808 | 90.50 | 75,000 |

| 2014[134] | 411,939 | 32,520 | 349,493 | 97.27 | 75,300 |

| 2015[135] | 249,248 | 16,150 | 336,758 | 82.82 | 73,500 |

| 2016[135] | 208,114 | 7,840 | 330,314 | 86.22 | 71,100 |

| 2017[136] | 244,363 | 19,710 | 348,691 | 81.86 | 69,600 |

| 2018[137] | 290,212 | 20,840 | 346,196 | 79.96 | 71,000 |

| 2019[138] | 264,938 | 14,340 | 362,597 | 73.73 | 74,900 |

Headquarters and offices

ExxonMobil's headquarters are located in Irving, Texas.[139]

The company has a new campus located in northern Houston.[140] This includes twenty office buildings totaling 3,000,000 square feet (280,000 m2), a wellness center, laboratory, and three parking garages.[141] It is designed to house nearly 10,000 employees with an additional 1,500 employees located in a satellite campus in Hughes Landing in The Woodlands, Texas.[142]

Board of directors

The current chairman of the board and CEO of Exxon Mobil Corp. is Darren W. Woods. Woods was elected chairman of the board and CEO effective January 1, 2017, after the retirement of former chairman and CEO Rex Tillerson. Before his election as chairman and CEO, Woods was elected president of ExxonMobil and a member of the board of directors in 2016.[143]

As of February 6, 2019, the current ExxonMobil board members are:[144]

- Susan Avery, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution president emerita

- Angela Braly, former president and CEO of WellPoint (now Anthem)

- Ursula Burns, Xerox former chairman and CEO

- Kenneth Frazier, chairman of the board, president and CEO of Merck & Co.

- Joseph Hooley

- Steven A. Kandarian, chairman, president and CEO of MetLife, Inc.

- Douglas R. Oberhelman, former chairman of the board and chief executive officer of Caterpillar Inc.

- Samuel J. Palmisano, former chairman of the board and CEO of IBM

- Steven Reinemund, an executive in residence of Wake Forest University, retired executive chairman of the board, PepsiCo

- William C. Weldon, former Johnson & Johnson chairman of the board and CEO

- Darren W. Woods, chairman of the board and CEO, ExxonMobil Corporation

Management committee

The current members of ExxonMobil management committee as of February 6, 2019, are:[145]

- Darren W. Woods, chairman, and CEO

- Neil A. Chapman, senior vice president

- Andrew P. Swiger, senior vice president, and principal financial officer

- Jack P. Williams, senior vice president

Environmental record

ExxonMobil's environmental record has faced much criticism for its stance and impact on global warming.[146] In 2018, the Political Economy Research Institute ranks ExxonMobil tenth among American corporations emitting airborne pollutants,[147] thirteenth by emitting greenhouse gases,[148] and sixteenth by emitting water pollutants.[149] A 2017 report places ExxonMobil as the fifth largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions from 1998 to 2015.[150][151]As of 2005, ExxonMobil had committed less than 1% of their profits towards researching alternative energy,[152] which, according to the advocacy organization Ceres, is less than other leading oil companies.[153]

Climate change

From the late 1970s through the 1980s, Exxon funded research broadly in line with the developing public scientific approach.[154] After the 1980s, Exxon curtailed its own climate research and was a leader in climate change denial.[155][156][157] In 2014, ExxonMobil publicly acknowledged climate change risk.[158] It nominally supports a carbon tax, though that support is weak.[159]

ExxonMobil funded organizations opposed to the Kyoto Protocol and seeking to influence public opinion about the scientific consensus that global warming is caused by the burning of fossil fuels.[157] ExxonMobil helped to found and lead the Global Climate Coalition, which opposed greenhouse gas emission regulation.[155] In 2007 the Union of Concerned Scientists said that ExxonMobil granted $16 million, between 1998 and 2005, towards 43 advocacy organizations which dispute the impact of global warming, and that ExxonMobil used disinformation tactics similar to those used by the tobacco industry in its denials of the link between lung cancer and smoking, saying that the company used many of the same organizations and personnel to cloud the scientific understanding of climate change and delay action on the issue.[160]

In 2015, the New York Attorney General launched an investigation whether ExxonMobil's statements to investors were consistent with the company's decades of extensive scientific research.[161][162] In October 2018, based on this investigation, ExxonMobil was sued by the State of New York, which claimed the company defrauded shareholders by downplaying the risks of climate change for its businesses.[163] On March 29, 2016, the attorneys general of Massachusetts and the United States Virgin Islands announced investigations. Seventeen attorney generals were cooperating on investigations.[164][165][166] In June, the attorneys general of the United States Virgin Islands withdrew the subpoena.[167] In December 2019, the New York Supreme Court issued a ruling in favor of Exxon Mobil Corporation. The ruling was written by New York Supreme Court Justice Barry Ostrager, who concluded that AG's office “failed to prove, by a preponderance of the evidence, that ExxonMobil made any material misstatements or omissions about its practices and procedures that misled any reasonable investor”.[168]

In 2019, InfluenceMap reported that ExxonMobil was among five major oil companies who were collectively spending $195M per year lobbying to block climate change policies.[169] In 2020, the investment arm of the Church of England asked other shareholders to not re-elect ExxonMobil's board at that year's AGM, saying that the firm's response to the climate crisis was "inadequate" and that it was "carrying on as if nothing has changed".[170] A month later, investment firm BlackRock stated it intended to vote against the re-election of two directors over the company's failure to make progress on environmental changes.[171]

ExxonMobil made several climate pledges: reduce methane emissions by 15% and reduce flaring by 25% by the year 2020. Canadian company 'Imperial Oil" affiliated with Exxon Mobil pledged to reduce carbon intensity by 10% by the year 2023.[172]

Sakhalin-I

Scientists and environmental groups have voiced concern that the Sakhalin-I oil and gas project in the Russian Far East, operated by an ExxonMobil subsidiary Exxon Neftegas, threatens the critically endangered western gray whale population.[173][174] Particular concerns were caused by the decision to construct a pier and to start shipping in Piltun Lagoon.[175] ExxonMobil has responded that since 1997 the company has invested over $40 million to the western whale monitoring program.[176]

New Jersey settlement

In 2004, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection sued ExxonMobil for $8.9 billion for lost wetland resources at Constable Hook in Bayonne and Bayway Refinery in Linden.[177] Although a New Jersey Superior Court justice was believed to be close to a ruling, the Christie Administration repeatedly asked the judge to wait, since they were reaching a settlement with ExxonMobil's attorneys.[178] On Friday, February 19, 2015, lawyers for the Christie administration informed the judge that a deal had been reached. Details of the $225 million settlement - roughly 3% of what the state originally sought - were not immediately released. Christopher Porrino served as Chief Counsel to the Christie administration from January 2014 through July 2015 and handled negotiations in the case.[179][180]

Human rights

ExxonMobil is the target of human rights violations accusations for actions taken by the corporation in the Indonesian territory of Aceh. In June 2001, a lawsuit against ExxonMobil was filed in the Federal District Court of the District of Columbia under the Alien Tort Claims Act.[181] The suit alleges that the ExxonMobil knowingly assisted human rights violations, including torture, murder and rape, by employing and providing material support to Indonesian military forces, who committed the alleged offenses during civil unrest in Aceh.[182] Human rights complaints involving Exxon's (Exxon and Mobil had not yet merged) relationship with the Indonesian military first arose in 1992; the company denies these accusations and filed a motion to dismiss the suit, which was denied in 2008 by a federal judge.[183] But another federal judge dismissed the lawsuit in August 2009.[184] The plaintiffs are currently appealing the dismissal.[185] ExxonMobil was ranked as the 12th best of 92 oil, gas, and mining companies on indigenous rights in its Arctic operations.[186][187]

Geopolitical influence

A July 2012 Daily Telegraph review of Steve Coll's book, Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power, says that he thinks that ExxonMobil is "able to determine American foreign policy and the fate of entire nations".[20] ExxonMobil increasingly drills in terrains leased to them by dictatorships, such as those in Chad and Equatorial Guinea.[20] Steve Coll describes Lee Raymond, the corporation's chief executive until 2005, as "notoriously skeptical about climate change and disliked government interference at any level".[20]

The book was also reviewed in The Economist, according to which "ExxonMobil is easy to caricature, and many critics have done so.... It is to Steve Coll's credit that Private Empire, his new book about ExxonMobil, refuses to subscribe to such a simplistic view." The review describes the company's power in dealing with the countries in which it drills as "constrained". It notes that the company shut down its operations in Indonesia to distance itself from the abuses committed against the population by that country's army and that it decided to drill in Chad only after the World Bank agreed to ensure that the oil royalties were used for the population's benefit. The review closes by noting that "A world addicted to ExxonMobil's product needs to look in the mirror before being too critical of how relentlessly the company supplies it."[188]

In 1937, Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), 23.75 percent owned by Near East Development Corporation (Later renamed ExxonMobil),[189] signed an oil concession agreement with the Sultan of Muscat. IPC offered financial support to raise an armed force that would assist the Sultan in occupying the interior region of Oman, an area that geologists believed to be rich in oil. This led to the 1954 outbreak of Jebel Akhdar War in Oman that lasted for more than 5 years.[190][191]

Accidents

Exxon Valdez oil spill

The March 24, 1989, Exxon Valdez oil spill resulted in the discharge of approximately 11 million US gallons (42,000 m3) of oil into Prince William Sound,[192] oiling 1,300 miles (2,100 km) of the remote Alaskan coastline. The Valdez spill is 36th worst oil spill in history in terms of sheer volume.

The State of Alaska's Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council stated that the spill "is widely considered the number one spill worldwide in terms of damage to the environment".[192] Carcasses were found of over 35,000 birds and 1,000 sea otters. Because carcasses typically sink to the seafloor, it is estimated the death toll may be 250,000 seabirds, 2,800 sea otters, 300 harbor seals, 250 bald eagles, and up to 22 killer whales. Billions of salmon and herring eggs were also killed.[193] It had a devastating effect on the local Alaska Native populations, many of which had for centuries relied largely on fishing to survive.[194]

As of 2001, oil remained on or under more than half the sound's beaches, according to a 2001 federal survey. The government-created Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council concluded that the oil disappears at less than 4 percent per year, adding that the oil will "take decades and possibly centuries to disappear entirely". Of the 27 species monitored by the council, 17 have not recovered. While the salmon population has rebounded, and the orca whales are recovering, the herring population and fishing industry have not.[195][196][197]

Exxon was widely criticized for its slow response to cleaning up the disaster. John Devens, the Mayor of Valdez, has said his community felt betrayed by Exxon's inadequate response to the crisis.[198] Exxon later removed the name "Exxon" from its tanker shipping subsidiary, which it renamed "SeaRiver Maritime". The renamed subsidiary, though wholly Exxon-controlled, has a separate corporate charter and board of directors, and the former Exxon Valdez is now the SeaRiver Mediterranean. The renamed tanker is legally owned by a small, stand-alone company, which would have minimal ability to pay out on claims in the event of a further accident.[199]

After a trial, a jury ordered Exxon to pay $5 billion in punitive damages, though an appeals court reduced that amount by half. Exxon appealed further, and on June 25, 2008, the United States Supreme Court lowered the amount to $500 million.[200]

In 2009, Exxon still uses more single-hull tankers than the rest of the largest ten oil companies combined, including the Valdez's sister ship, the SeaRiver Long Beach.[201]

Exxon's Brooklyn oil spill

New York Attorney General Andrew Cuomo announced on July 17, 2007 that he had filed suit against the Exxon Mobil Corp. and ExxonMobil Refining and Supply Co. to force cleanup of the oil spill at Greenpoint, Brooklyn, and to restore Newtown Creek.[202]

A study of the spill released by the US Environmental Protection Agency in September 2007 reported[203] that the spill consists of 17 to 30 million US gallons (64,000 to 114,000 m3) of petroleum products from the mid-19th century to the mid-20th century.[204] The largest portion of these operations were by ExxonMobil or its predecessors. By comparison, the Exxon Valdez oil spill was approximately 11 million US gallons (42,000 m3).[192] The study reported that in the early 20th century Standard Oil of New York operated a major refinery in the area where the spill is located. The refinery produced fuel oils, gasoline, kerosene and solvents. Naptha and gas oil, secondary products, were also stored in the refinery area. Standard Oil of New York later became Mobil, a predecessor to Exxon/Mobil.[205]

Baton Rouge Refinery pipeline oil spill

In April 2012, a crude oil pipeline, from the Exxon Corp Baton Rouge Refinery, burst and spilled at least 1,900 barrels of oil (80,000 gallons) in the rivers of Point Coupee Parish, Louisiana, shutting down the Exxon Corp Baton Refinery for a few days. Regulators opened an investigation in response to the pipeline oil spill.[206]

Baton Rouge Refinery benzene leak

On June 14, 2012, a bleeder plug on a tank in the Baton Rouge Refinery failed and began leaking naphtha, a substance that is composed of many chemicals including benzene.[207] ExxonMobil originally reported to the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) that 1,364 pounds of material had been leaked.

On June 18, Baton Rouge refinery representatives told the LDEQ that ExxonMobil's chemical team determined that the June 14 spill was actually a level 2 incident classification, which means that a significant response to the leak was required.[208] On the day of the spill the refinery did not report that their estimate of spilled materials was significantly different from what was originally reported to the department. Because the spill estimate and the actual amount of chemicals spilled varied drastically, the LDEQ launched an in-depth investigation on June 16 to determine the actual amounts of chemicals spilled as well as to find out what information the refinery knew and when they knew it.[209] On June 20, ExxonMobil sent an official notification to the LDEQ saying that the leak had actually released 28,688 pounds of benzene, 10,882 pounds of toluene, 1,100 pounds of cyclohexane, 1,564 pounds of hexane and 12,605 pounds of additional volatile organic compound.[208][209] After the spill, people living in neighboring communities reported adverse health impacts such as severe headaches and respiratory difficulties.[210]

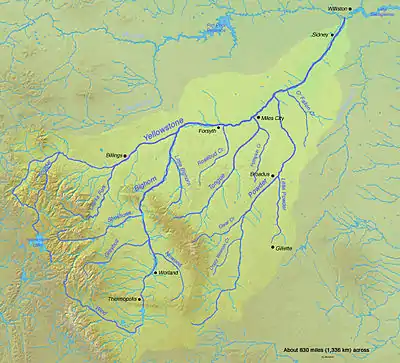

Yellowstone River oil spill

The July 2011 Yellowstone River oil spill was an oil spill from an ExxonMobil pipeline running from Silver Tip to Billings, Montana, which ruptured about 10 miles west of Billings on July 1, 2011, at about 11:30 pm.[211] The resulting spill leaked an estimated 1,500 barrels of oil into the Yellowstone River for about 30 minutes before it was shut down, resulting in about $135 million in damages.[212] As a precaution against a possible explosion, officials in Laurel, Montana evacuated about 140 people on Saturday (July 2) just after midnight, then allowed them to return at 4 am.[211]

A spokesman for ExxonMobil said that the oil is within 10 miles of the spill site. However, Montana Governor Brian Schweitzer disputed the accuracy of that figure.[213] The governor pledged that "The parties responsible will restore the Yellowstone River."[214]

Mayflower oil spill

On March 29, 2013, the Pegasus Pipeline, owned by ExxonMobil and carrying Canadian Wabasca heavy crude, ruptured in Mayflower, Arkansas, releasing about 3,190 barrels (507 m3) of oil and forcing the evacuation of 22 homes.[215][216] The Environmental Protection Agency has classified the leak as a major spill.[217] In 2015, ExxonMobil settled charges that it violated the federal Clean Water Act and state environmental laws, for $5.07 million, including $4.19 million in civil penalties. It did not admit liability.[215]

See also

Notes

- EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION Form 10-K

- "ExxonMobil, Our History". Exxon Mobil Corp. Archived from the original on December 2, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- "ExxonMobil, Our Brands". Exxon Mobil Corp. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- "10-K". 10-K. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- "Apple loses title of world's most valuable company to Exxon". Fox News. April 17, 2013. Archived from the original on April 18, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- "Fortune 500". Forbes. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- DeCarlo, Scott. "ExxonMobil - In Photos: Global 2000: The World's Top 25 Companies". Forbes. Archived from the original on February 6, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- "The 10 most profitable companies of the Fortune 500". Fortune. Archived from the original on March 10, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- "Fortune Global 500 List 2018". Fortune. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- "The new Seven Sisters: oil and gas giants dwarf western rivals". Financial Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2008. Retrieved April 21, 2008.

- "Will We Rid Ourselves of This Pollution?". Forbes. April 16, 2007. Archived from the original on March 30, 2009. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- "EIA – Statement of Jay Hakes". Tonto.eia.doe.gov. March 10, 1999. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "Exxon Mobil Corporation Announces 2013 Reserves Replacement Totaled". marketwatch.com. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- "Top 10 large oil refineries". Hydrocarbons Technology. Archived from the original on November 14, 2008. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Exxon Mobil – Company profile". Exxon Mobil Corp. Archived from the original on November 14, 2008. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- "Natural Gas Marketing". PetroStrategies, Inc. March 14, 2018.

- Holusha, John (April 21, 1989). "Exxon's Public-Relations Problem". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- "11 Major Oil Spills Of The Maritime World". Marine Insight. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- "Environmental Protection". ExxonMobil. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- Ian Thompson (July 30, 2012). "Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on February 11, 2018. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- Brooks, Nancy Rivera (December 2, 1998). "Exxon and Mobil Agree to Biggest Merger Ever". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- "A Guide to the ExxonMobil Historical Collection, 1790–2004: Part 1. Historical Note". Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- "Anglo-American Oil Co". Grace Guide. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- "Exxon Corporation". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on December 2, 2015. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- Clark, Peter (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Cities in World History. OUP Oxford. p. 816. ISBN 978-0-19-163769-8. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- Krabbendam, Hans; van Minnen, Cornelis A.; Scott-Smith, Giles (2009). Four Centuries of Dutch-American Relations: 1609–2009. SUNY Press. p. 548. ISBN 978-1-4384-3013-3. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- Skinner, Walter R. (1983). Financial Times Oil and Gas International Year Book. Financial Times. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-582-90315-9.

- Cochran, Sherman (2000). Encountering Chinese Networks: Western, Japanese, and Chinese Corporations in China, 1880–1937. University of California Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-520-92189-4.

- Vassiliou, Marius (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Petroleum Industry. Scarecrow Press. pp. 186–189, 472–474. ISBN 978-0-8108-6288-3. Archived from the original on May 19, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- "Business & Finance: Socony-Vacuum Corp". Time. August 10, 1931. Archived from the original on August 12, 2013. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- Shavit, David (1990). The United States in Asia: A Historical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-313-26788-8. Archived from the original on May 14, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- Pound, Arthur (2013). The Turning Wheel – The story of General Motors through twenty-five years 1908–1933. Edizioni Savine. p. 360. ISBN 978-88-96365-39-7. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- Lesch, John (2013). The German Chemical Industry in the Twentieth Century. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 185–191. ISBN 978-94-015-9377-9. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- Herbert, Vernon; Bisio, Attilio (1985). Synthetic Rubber: A Project that Had to Succeed. Greenwood Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-313-24634-0. ISSN 0084-9235.

- Nowell, Gregory Patrick (1994). Mercantile States and the World Oil Cartel, 1900–1939. Cornell University Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-8014-2878-4. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- "Butyl Rubber: A Techno-commercial Profile". Chemical Weekly. 55 (12): 207–211. November 3, 2009.

- Morton, M, ed. (2013). Rubber Technology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 285. ISBN 9789401729253. Archived from the original on February 9, 2017. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- Rockoff, Hugh (2012). America's Economic Way of War: War and the US Economy from the Spanish–American War to the Persian Gulf War. Cambridge University Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-107-37718-9. Archived from the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- Smith, William D. (October 25, 1972). "And Now the Esso Name Is History". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2019. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- "The Return of Esso Gasoline?". CSP Daily News. February 16, 2016. Archived from the original on August 30, 2018. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- "Oil Port Can Service City of Half a Million". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. 64 (4): 543. 1935. ISBN 9780810862883. ISSN 0032-4558. Archived from the original on May 19, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- Darr, Alan. "The Gilmore Oil Company: 1900–1940". CrossRoads Access, Inc. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- Tjemkes, Brian; VosBurgers, Pepijn; Burgers, Koen (2013). Strategic Alliance Management. Routledge. pp. 217–218. ISBN 9781136465727. Archived from the original on February 9, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- Green, Michael S.; Stabler, Scott L., eds. (2015). Ideas and Movements that Shaped America: From the Bill of Rights to "Occupy Wall Street". ABC-CLIO. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-61069-252-6. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- Chakravarthy, Balaji S. (1981). Managing Coal: A Challenge in Adaption. SUNY Press. p. 132. ISBN 9780791498682. Archived from the original on February 8, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- Kent, James A. (2013). Riegel's Handbook of Industrial Chemistry (9, illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 574. ISBN 978-1-4757-6431-4. Archived from the original on February 8, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- Weiand, Achim (2006). BP acquires Veba Oel and Aral. Post-Merger Integration and Corporate Culture (PDF). Bertelsmann Stiftung. pp. 24–27. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- Williams, Neville (2005). Chasing the Sun: Solar Adventures Around the World. Working Paper 12-105. New Society Publishers. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-55092-312-4.

- Perlin, John (1999). From Space to Earth: The Story of Solar Electricity. Harvard University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-674-01013-0. Archived from the original on May 22, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- Jones, Geoffrey; Bouamane, Loubna (2012). "Power from Sunshine": A Business History of Solar Energy (PDF). Harvard Business School. pp. 22–23. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- Roston, Eric (November 4, 2015). "Exxon Predicted Today's Cheap Solar Boom Back in the 1980s". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on January 28, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- Mühlbauer, Alfred (2008). History of Induction Heating and Melting. Vulkan-Verlag. p. 48. ISBN 978-3-8027-2946-1.

- "T.V.A. v. Exxon Nuclear Co., INC. Memorandum by Chief Judge Robert L. Taylor". Leagle, Inc. August 22, 1983. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- "AREVA Inc.'s Richland Fuel Manufacturing Facility Celebrates 45 Years of Innovation and Excellence" (Press release). Areva, Inc. October 30, 2015. Archived from the original on November 22, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- Ferguson, Robert L. (2014). Nuclear Waste in Your Backyard: Who's to Blame and How to Fix It. Archway Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-4808-0860-7. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- Roston, Eric (December 24, 1986). "Exxon Plans Sale Of Nuclear Unit". The New York Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- "Exxonmobil Highlands". Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- "ExxonMobil Corporation (State of Texas)". Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- "Carbones del Cerrejón, Colombia". Mining Technology. Archived from the original on December 25, 2015. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- O'Brien, Michael (2008). Exxon and the Crandon Mine Controversy. Badger Books Inc. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-932542-37-0. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- "Tosco Corporation". Funding Universe. Archived from the original on September 9, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- Symington, William A. (2008). Heat Conduction Modeling Tools for Screening In Situ Oil Shale Conversion Processes (PDF). 28th Oil Shale Symposium. Colorado School of Mines. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- Dawson, Jennifer (January 15, 2010). "Exxon Mobil campus 'clearly happening'". Houston Business Journal. Archived from the original on September 16, 2010. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

- Pearson, Anne and Ralph Bivins. "Exxon moving corporate headquarters to Dallas Archived October 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine." Houston Chronicle. Friday October 27, 1989. A1. Retrieved on July 29, 2009.

- Bolstad, Erika (June 25, 2008). "Supreme Court slashes punitive award in Exxon Valdez oil spill". McClatchyDC. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- "Mobil establishes new European gas group". The Virginian-Pilot. November 10, 1994. Archived from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- "Commission clears joint venture between BP and Mobil" (Press release). European Commission. August 7, 1996. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- Sapulkas, Agis (June 11, 1996). "Exxon Moves On Sakhalin Oilfield Deal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 3, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- "Oil merger faces monopoly probe". BBC News. December 2, 1998. Archived from the original on February 3, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- "Exxon and Mobil Announce $80 Billion Deal to Create World's Largest Company". NY Times. December 3, 1998. Archived from the original on March 7, 2017. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- "Commission agrees to dissolution of BP/Mobil Joint Venture, a European fuel and lubricants producer and retailer; the dissolution was a condition of the ExxonMobil merger clearance decision" (Press release). European Commission. September 29, 1999. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- Wilke, John R.; Barrionuevo, Alexei; Liesman, Steve (December 1, 1999). "Exxon-Mobil Merger Gets Approval; FTC May Be Tougher on Future Deals". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- "Commission agrees to dissolution of BP/Mobil Joint Venture, a European fuel and lubricants producer and retailer; the dissolution was a condition of the ExxonMobil merger clearance decision" (Press release). European Commission. March 2, 2000. Archived from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- "Exxon-Mobil merger wins approval in EU, awaits US decision". Oil & Gas Journal. 97 (43). Pennwell Corporation. October 25, 1999. p. 24. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- "Exxon Mobil to sell Mobil Europe Gas". Dallas Business Journal. April 3, 2000. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- Rudnick, Leslie R., ed. (2013). Synthetics, Mineral Oils, and Bio-Based Lubricants: Chemistry and Technology (2, illustrated, revised ed.). CRC Press. p. 920. ISBN 978-1-4398-5538-6. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- "Exxon-Mobil merger done". CNN. November 30, 1999. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- "Exxon/Mobil Agree to Largest FTC Divestiture Ever in Order to Settle FTC Antitrust Charges; Settlement Requires Extensive Restructuring and Prevents Merger of Significant Competing U.S. Assets" (Press release). Federal Trade Commission. November 30, 1999. Archived from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- "Valero acquires California refinery, outlets". Oil & Gas Journal. 98 (11). Pennwell Corporation. March 13, 2000. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- "Anglo American to Buy Copper Mines In Chile From Exxon for $1.3 Billion". The Wall Street Journal. May 3, 2002. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- Webb, Dennis (March 11, 2014). "Back in oil shale". The Daily Sentinel. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- Peixe, Joao (March 18, 2014). "ExxonMobil Takes Step Forward on Colorado Oil Shale". Oilprice.com. Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- "ExxonMobil again retreats from oil shale". The Daily Sentinel. March 27, 2016. Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- "ExxonMobil sells Monterey coal mine". The State Journal-Register. January 27, 2009. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- Erman, Michael (June 12, 2008). "Exxon to exit U.S. retail gas business". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- "ExxonMobil and XTO complete merger". Upstream Online. NHST Media Group. June 25, 2010. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- Klein, Ezra (August 30, 2011). "ExxonMobil signs Russian oil pact". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- Ordonez, Isabel; Stilwell, Victoria (June 15, 2012). "Exxon Expands Rosneft Alliance to Siberian Shale". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- Overland, Indra; Godzimirski, Jakub; Lunden, Lars Petter; Fjaertoft, Daniel (2013). "Rosneft's offshore partnerships: the re-opening of the Russian petroleum frontier?". Polar Record. 49 (2): 140–153. doi:10.1017/S0032247412000137. ISSN 0032-2474.

- Fjaertoft, Daniel; Overland, Indra (2015). "Financial Sanctions Impact Russian Oil, Equipment Export Ban's Effects Limited". Oil and Gas Journal. 113: 66–72. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- Foy, Henry; Crooks, Ed (March 1, 2018). "ExxonMobil abandons joint ventures with Russia's Rosneft". The Financial Times. Archived from the original on March 3, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- Scheyder, Ernest; Soldatkin, Vladimir (February 28, 2018). "Exxon quits some Russian joint ventures citing sanctions". Reuters. Archived from the original on March 2, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- Chambers, Matt (December 17, 2014). "ExxonMobil pulls out of Victorian coal-seam gas venture". The Australian. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- "Exxon Confirms Deals With Iraqi Kurds". The Wall Street Journal. February 27, 2012. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- Denny Thomas; Charlie Zhu (November 19, 2013). "Exxon to sell Hong Kong power operations for $3.4 billion". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- "ExxonMobil, Linn to make second asset exchange this year". Oil & Gas Journal. Pennwell Corporation. September 19, 2014. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- Chamberlin, Alex. "The World Bank ruling on the Exxon Mobil Venezuela case". Market Realist. Market Realist, Inc. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- Shell Oil's Stark Climate Change Warning from 1991 on YouTube

- Damian Carrington and Jelmer Mommers (February 28, 2017). "'Shell knew': oil giant's 1991 film warned of climate change danger". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Clifford Krauss (September 20, 2016). "S.E.C. Is Latest to Look Into Exxon Mobil's Workings". NYT. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- Aruna Viswanatha and Bradley Olson (September 20, 2016). "SEC Probes Exxon Over Accounting for Climate Change; Probe also examines company's practice of not writing down the value of oil and gas reserves". WSJ. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- Liam Denning (September 21, 2016). "Just Another Cloud In Exxon's Sky". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- Hiroko Tabuchi and Clifford Krauss (September 20, 2016). "A New Debate Over Pricing the Risks of Climate Change". NYT. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- "How to deal with worries about stranded assets, Oil companies need to heed investors' concerns". The Economist. November 26, 2016. Archived from the original on December 5, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- Clifford Krauss (October 28, 2016). "Exxon Concedes It May Need to Declare Lower Value for Oil in Ground". Nytimes.com. The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 13, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- "After 78 Years, Exxon Asks Court To Use 'Esso' Name Again". CSP Daily News. December 21, 2015. Archived from the original on December 16, 2018. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- "Rex Tillerson, Exxon C.E.O., Chosen as Secretary of State". The New York Times. December 13, 2016. Archived from the original on November 22, 2018. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- David Hasemyer (January 5, 2017). "Federal Climate Investigation of Exxon Likely to Fizzle Under Trump". InsideClimate News. Archived from the original on January 19, 2017. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- "ExxonMobil and Iran did business under Secretary of State nominee Tillerson". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- "The Trump administration has denied ExxonMobil permission to bypass sanctions to drill for oil in Russia". CNN. April 21, 2017. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- "Exxon Mobil Sues U.S. Over Penalty For Post-Sanctions Russian Deal Archived June 25, 2018, at the Wayback Machine". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL). July 20, 2017.

- "Rocket hits ExxonMobil, other oil firms in Iraq". NBC News. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- McCormick, Myles (October 5, 2020). "ExxonMobil to axe 1,600 jobs in Europe". Financial Times. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- "Exxon Mobil eyes multi-billion dollar investment at Singapore refinery | Market Report Company - analytics, Prices, polyethylene, polypropylene, polyvinylchloride, polystyrene, Russia, Ukraine, Europe, Asia, reports". www.mrcplast.com. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- TopBlog. "Energy Choices: ExxonMobil - Exxon Energy". Energy Choices (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- "Financial operations overview and highlights | ExxonMobil". ExxonMobil. Archived from the original on October 24, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- Driver, Anna (February 23, 2015). "Exxon Mobil 2014 reserves up on oil sands, shale". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- "Exxon Mobil Corp (XOM)". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 9, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- Toweh, Alphonso (November 13, 2015). "Exxon Mobil to drill offshore post-Ebola Liberia". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- Bavier, Joe (December 17, 2014). "Ivory Coast signs deals with ExxonMobil for two oil blocks". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- Rabary, Lovasoa (July 4, 2015). "Exxon Mobil ends oil exploration in Madagascar after poor finds -minister". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- DiLallo, Matthew (September 29, 2018). "ExxonMobil's Proposed Permian Oil Pipeline Takes Another Step Forward". The Motley Fool. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- DiLallo, Matthew (June 15, 2019). "Where Will ExxonMobil Be in 5 Years?". The Motley Fool. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- "Exxon in Talks to Restructure Stake in Japan Refining Unit". January 5, 2012. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- Okada, Yuji; Adelman, Jacob (January 30, 2012). "TonenGeneral to Buy Exxon Japan Refining, Marketing Unit for $3.9 Billion". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- "ExxonMobil chemicals: petrochemicals since 1886". ExxonMobil.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- "Infineum". Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- Hirtenstein, Anna (November 3, 2017). "Exxon Quietly Researching Hundreds of Green Projects". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on March 18, 2018. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- "2009 Annual Report" (PDF). Annualreports.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "2010 Annual Report" (PDF). Annualreports.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 3, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "2011 Annual Report" (PDF). Annualreports.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "2012 Annual Report" (PDF). Annualreports.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "2013 Annual Report" (PDF). Annualreports.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "2014 Annual Report" (PDF). Annualreports.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "2016 Annual Report" (PDF). Annualreports.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "ExxonMobil Earns $19.7 Billion in 2017; $8.4 Billion in Fourth Quarter". ExxonMobil News Releases. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "2018 SUMMARY ANNUAL REPORT" (PDF). ExxonMobil News Releases. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 14, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- "2020 Annual Report" (PDF). Exxon Mobil.

- "Business Headquarters Archived July 12, 2012, at WebCite." ExxonMobil. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- "ExxonMobil's New Campus: Giving Houston a Second Energy Corridor". Urban Land Magazine. May 4, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- Sarnoff, Nancy (January 28, 2010). "ExxonMobil is considering a move". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 31, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- Stephens, Matt (January 14, 2014). "ExxonMobil announces plans to open two new offices in Hughes Landing". impact. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- "Exxon Mobil Corporation, Form 8-K, Current Report, Filing Date Dec 16, 2016" (PDF). secdatabase.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- "Exxon Mobil Corp. Board of Directors". Exxon Mobil Corp. Archived from the original on July 26, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- "Exxon Mobil Corp. Management Committee". Exxon Mobil Corp. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- "Big US Pension Fund Joins Critics Of ExxonMobil Climate Stance". Energy-daily.com. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "Toxic 100 Air Polluters Index (2018 Report, Based on 2015 Data)". Political Economy Research Institute. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- "Greenhouse 100 Polluters Index (2018 Report, Based on 2015 Data)". Political Economy Research Institute. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- "Toxic 100 Water Polluters Index (2018 Report, Based on 2015 Data)". Political Economy Research Institute. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- Riley, Tess (July 10, 2017). "Just 100 companies responsible for 71% of global emissions, study says". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- "New report shows just 100 companies are source of over 70% of emissions - CDP". www.cdp.net. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Mufson, Steven (April 2, 2008). "Familiar Back and Forth With Oil Executives". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "ERES: ExxonMobil Shareholders Relying on Fumes". Heatisonline.org. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- Jerving, Sara; Jennings, Katie; Hirsch, Masako Melissa; Rust, Susanne (October 9, 2015). "What Exxon knew about the Earth's melting Arctic". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 20, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- Banerjee, Neela; Song, Lisa; Hasemyer, David (September 21, 2015). "Exxon's Own Research Confirmed Fossil Fuels' Role in Global Warming Decades Ago; Top executives were warned of possible catastrophe from greenhouse effect, then led efforts to block solutions". InsideClimate News. Archived from the original on October 13, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

Exxon helped to found and lead the Global Climate Coalition, an alliance of some of the world's largest companies seeking to halt government efforts to curb fossil fuel emissions.

- Lever-Tracy, Constance (2010). Routledge Handbook of Climate Change and Society. Taylor & Francis. p. 256. ISBN 9780203876213. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

major figures from the US (such as Exxon Mobil, conservative think-tanks and leading contrarian scientists) have helped spread climate change denial to other nations.