Strangle (options)

In finance, a strangle is a trading strategy involving the purchase or sale of particular option derivatives that allows the holder to profit based on how much the price of the underlying security moves, with relatively minimal exposure to the direction of price movement. A purchase of particular options is known as a long strangle, while a sale of the same options is known as a short strangle. As an options position strangle is a variation of a more generic straddle position. Strangle's key difference from a straddle is in giving investor choice of balancing cost of opening a strangle versus a probability of profit. For example, given the same underlying security, strangle positions can be constructed with low cost and low probability of profit. Low cost is relative and comparable to a cost of straddle on the same underlying. Strangles can be used with equity options, index options or options on futures.

Long strangle

The long strangle involves going long (buying) both a call option and a put option of the same underlying security. Like a straddle, the options expire at the same time, but unlike a straddle, the options have different strike prices. A strangle can be less expensive than a straddle if the strike prices are out-of-the-money. If the strike prices are in-the-money, the spread is called a gut spread. The owner of a long strangle makes a profit if the underlying price moves far enough away from the current price, either above or below. Thus, an investor may take a long strangle position if he thinks the underlying security is highly volatile, but does not know which direction it is going to move. This position is a limited risk, since the most a purchaser may lose is the cost of both options. At the same time, there is unlimited profit potential.[1]

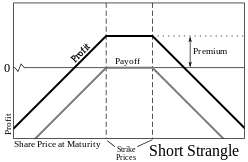

Short strangle

The short strangle strategy requires the investor to simultaneously sell both a [call] and a [put] option on the same underlying security. The strike price for the call and put contracts must be, respectively, above and below the current price of the underlying. The assumption of the investor (the person selling the option) is that, for the duration of the contract, the price of the underlying will remain below the call and above the put strike price. If the investor's assumption is correct the party purchasing the option has no advantage in exercising the contracts so they expire worthless. This expiration condition frees the investor from any contractual obligations and the money (the premium) he or she received at the time of the sale becomes profit. Importantly, if the investor's assumptions against volatility are incorrect the strangle strategy leads to modest or unlimited loss.

References

- Barrie, Scott (2001). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Options and Futures. Alpha Books. pp. 120–121. ISBN 0-02-864138-8.