Subduction polarity reversal

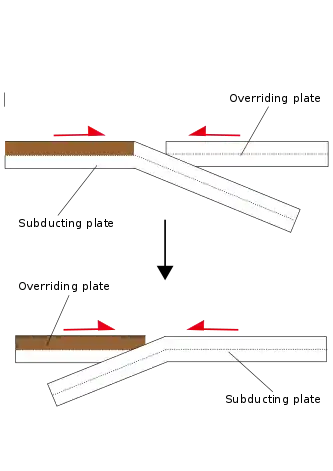

Subduction polarity reversal is a geologic process in which two converging plates switch roles: The over-lying plate becomes the down-going plate, and vice versa. There are two basic units which make up a subduction zone. This consists of an overriding plate and the subduction plate.[1] Two plates move towards each other due to tectonic forces.[1] The overriding plate will be on the top of the subducting plate.[1] This type of tectonic interaction is found at many plate boundaries.[1]

However, some geologists propose that the roles of the overriding plate and subducting plate do not remain the same indefinitely.[2] Their roles will swap, which means the plate originally subducting beneath will become the overriding plate.[2] This phenomenon is called subduction switch,[3] the flipping of subduction polarity[4] or subduction polarity reversal.[2]

Examples of subduction systems with subduction polarity reversal are:

Background

The phenomenon of subduction polarity reversal has been identified in the collision of an intra-oceanic subduction system,[12] which is the collision of two oceanic plates.[1] When two oceanic plates migrate towards each other, one subducts below the other. Generally, the oceanic plate with higher density subducts beneath and the other one overrides the down-going slab.[1] The process continues until a buoyant continental margin sitting on the top of the subducting plate is introduced into the down-going slab.[2][4] The subduction of the slab becomes slower and may even cease.[2][4] Geologists propose various possible models to predict what will be the next step for the intra-oceanic subduction system with the involvement of buoyant continental crust.[2][4] One of the possible results is subduction polarity reversal.[4][11][12][13][14][15]

Models of subduction polarity reversal

Even though many geologists agree that after the involvement of buoyant continental crust, subduction polarity reversal may occur, they have different opinions towards the mechanisms leading to the change of subduction direction. Thus, there is no single model to represent subduction polarity reversal. How geologists develop the models depends on the parameters they focus on.[1] Some geologists attempt to construct models of subduction reversal through laboratory experiments[2][12][13] or observations.[4][16] There are three common models: slab break-off,[4] double convergence[16] and lithospheric break-up.[2]

The models of slab-break up[4] and double convergence are based on observations by geologists,[16] and the lithosphere break-up model is based on experimental simulation.[2]

The criteria for having subduction polarity reversal are

- Intra-oceanic subduction system with a buoyant continental plate

- Subduction system ceases with the involvement of continental plate

- Old slab breaks off[2][4]

Different models representing the subduction polarity reversal depends highly on parameters the Geologists considered. Here is the summary table showing the comparison models.

| Difference | Slab break-off | Double convergence | Lithospheric break-up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reasons of slab break-off | Tensile force at the old slab | Lateral sliding by the new slab | Pre-existing fault leads to penetration of new slab |

| Accommodation of new slab | Mantle window | A deep strike-slip movement | Penetration of new slab breaks off the old slab |

Slab break-off

This model was developed by analyzing the geological cross section along the collision between Eurasian plate and the Philippine sea plate, which is the location of an ongoing flipping of subduction polarity.[4]

When two oceanic plates migrate towards each other, one plate overrides another forming a subduction system. Later, a light and buoyant passive continental margin introduced into this system will cause the cessation of subduction system.[4] On one hand, the buoyant plate resists subduction beneath the overriding plate.[4] On the other hand, the dense oceanic slab at the subducting plate prefers to move downward.[4] These opposite forces will generate a tensile force or gravitational instability on the downward slab and lead to the break-off of the slab.[17] The space where the break-off slab separates will form a mantle window.[4] Subsequently, the less dense continental margin forms the overriding plate, while the oceanic plate becomes the subducting slab.[4] The direction of the subduction system changes since the break-off of slab creates the space, which is the major parameter of this model.[4]

Double convergence model

This model is developed based on the geological evolution of Alpine and Apennine subduction.[16]

Similarly, two oceanic plates move towards each other. The subduction process ceases with the involvement of buoyant continental block. A new slab is formed at the overriding plate owing to the regional compression and the difference in density between the continental block and oceanic plate.[16] An orogenic wedge is built.[16] However, there is an obvious space problem about how to accommodate two slabs. The solution is the new developing slab moves not only vertically, but also laterally leading to a deep strike-slip movement.[16] The development of co-existence of two opposite slabs is described as a double sided subduction[18] or doubly convergent wedge.[16] Eventually, the development of new slab grows and slides onto the old slab. The old slab breaks off and the orogenic wedge collapses. The new slab stops the lateral motion and subducts beneath.[16] The direction of subduction system changes.[16]

Lithosphere break-up

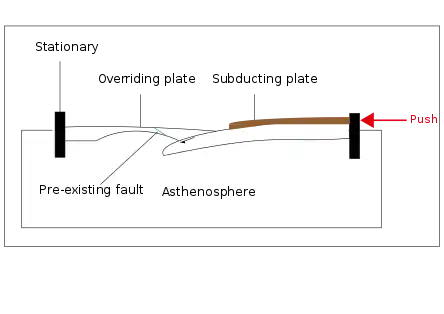

The lithosphere break-up model is simulated by hydrocarbon experiments in the laboratory.[2] The researchers set up the setting of subduction zone which are analogized by hydrocarbons with different densities representing various layers in the subduction zone.[2]

The initial setting of the simulated subduction zone model is confined by two pistons. The piston connected to the overriding plate is locked, while the piston linking to subducting plate is subjected to a constant rate of compression.[2] More importantly, there is a relatively thin magmatic arc and pre-existing fault dipping towards the subducting plate at the overriding plate.[2] The detachment of the pre-existing fault occurs when buoyant continental margin is in contact with the overriding plate.[2] It is because the buoyant margin resists subduction and significantly increases the frictional force in the contact region.[2] The subduction then stops. Subsequently, the new subducting slab develops at an overriding plate with the continuous compression.[2] The new developing slab eventually penetrates and breaks the old slab.[2] A new subduction zone is formed with an opposite polarity to the previous one.[2]

In reality, the magmatic arc is a relatively weak zone at the overriding plate because it has a thin lithosphere and is further weakened by high heat flow[19][20] and hot fluid.[21][22] Pre-existing faults in this simulation are also common in the magmatic arc.[23] This experiment is a successful analogy to subduction polarity reversal happening at Kamchatka in early Eocene[7][24] and the active example at Taiwan region[2][11] as well as at Timor.[25][26]

Taiwan as an active example of flipping of subduction reversal

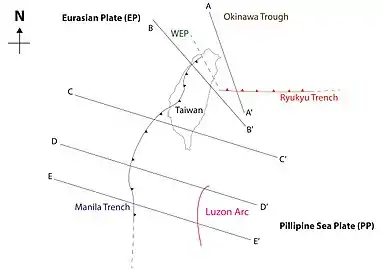

A sharp contrast of landforms in Taiwan lures many people to investigate. The northern part of Taiwan has many flat plains such as Ilan Plain and Pingtung Plain,[27] while the southern part of Taiwan is concentrated with many high mountains like Yushan reaching about 3950m. This huge difference in topography is the consequence of the flipping of subduction polarity.[4] Most of models studying this phenomenon will focus on an active collision in Taiwan which appears to reveal the incipient stages of subduction reversal.[4][11][12][13][14][15]

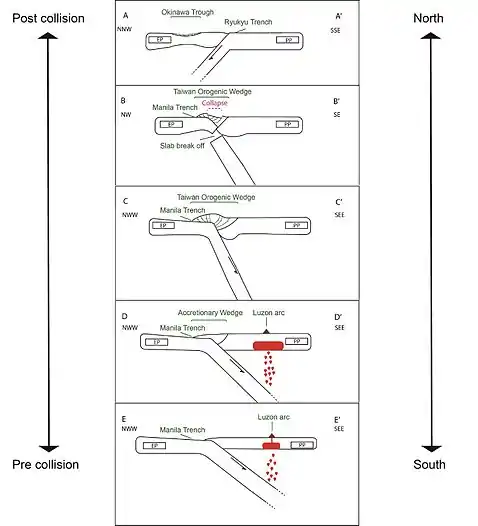

The collision of N- trending Luzon arc in Philippine Sea plate (PP) with E-trending Eurasian plate (EP) started at mid-Miocene[4] forming an intra-oceanic subduction system.[12][28] Taiwan was formed by this process. The south-north topographic difference in Taiwan is like a story book telling the evolution in subduction zone. The Philippine Sea plate subducts below the Eurasian plate at south-west part of WEP (Western edge of north-dipping Philippine Sea Plate),[4] and the latter overrides the former at north east part of WEP.[4] The collision between two plates started at the Northern Taiwan and propagated south with the younger region at the southern part. Each incipient stage of subduction reversal process could be studied by correlating cross-sections in various parts of Taiwan.[29]

2) Cross-section B-B’:[4] The Philippine Sea Plate subducts beneath the Eurasian plate, and Ryukyu trench roll-back leads to the extensional collapse of Taiwan orogenic wedge.[27] The direction of subduction changes in cross-section C-C'.

3) Cross-section C-C’:[4] Drastic collision between two plate creates an accretionary wedge and develops orogenic belt. Taiwan orogens reached the maximum height with an equal amount of erosion and growth rate.[30] The angle of the slab is almost 80 degrees dipping downward.[31]

4) Cross-section D-D’:[4] The Eurasian plate is actively subducting into the Philippine Sea plate at 80mm/year along the Manila Trench.[27] The slab is penetrating into the mantle and the volume of melt in mantle wedge keeps increasing. Meanwhile, the angle of subduction slab is not as steep as in cross-section C-C'.[31] The accretionary wedge was just developed.

5) Cross-section E-E’ [4](Pre-Collision): Slab penetrates beneath the Philippine Sea plate and brings hydrous materials to generate a mantle wedge[4] and Luzon volcanic arc.

References

- Arc-Continent Collision | Dennis Brown | Springer. Frontiers in Earth Sciences. Springer. 2011. ISBN 9783540885573.

- Chemenda, A. I.; Yang, R. -K.; Stephan, J. -F.; Konstantinovskaya, E. A.; Ivanov, G. M. (2001-04-10). "New results from physical modelling of arc–continent collision in Taiwan: evolutionary model". Tectonophysics. 333 (1–2): 159–178. Bibcode:2001Tectp.333..159C. doi:10.1016/S0040-1951(00)00273-0.

- Willett, S. D.; Beaumont, C. (1994-06-23). "Subduction of Asian lithospheric mantle beneath Tibet inferredfrom models of continental collision". Nature. 369 (6482): 642–645. Bibcode:1994Natur.369..642W. doi:10.1038/369642a0.

- Teng, Louis S.; Lee, C. T.; Tsai, Y. B.; Hsiao, Li-Yuan (2000-02-01). "Slab breakoff as a mechanism for flipping of subduction polarity in Taiwan". Geology. 28 (2): 155–158. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2000)28<155:sbaamf>2.0.co;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

- Ryan, P. D.; Dewey, J. F. (2011-01-01). Arc-Continent Collision. Frontiers in Earth Sciences. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 373–401. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-88558-0_13. ISBN 9783540885573.

- Molli, G.; Malavieille, J. (2010-09-28). "Orogenic processes and the Corsica/Apennines geodynamic evolution: insights from Taiwan". International Journal of Earth Sciences. 100 (5): 1207–1224. Bibcode:2011IJEaS.100.1207M. doi:10.1007/s00531-010-0598-y. ISSN 1437-3254.

- Konstantinovskaia, E. A (2001-04-10). "Arc–continent collision and subduction reversal in the Cenozoic evolution of the Northwest Pacific: an example from Kamchatka (NE Russia)". Tectonophysics. 333 (1–2): 75–94. Bibcode:2001Tectp.333...75K. doi:10.1016/S0040-1951(00)00268-7.

- Hamilton, Warren Bell; Pertambangan, Indonesia Departemen; Development, United States Agency for International (1979-01-01). Tectonics of the Indonesian region. U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

- McCaffrey, Robert; Molnar, Peter; Roecker, Steven W.; Joyodiwiryo, Yoko S. (1985-05-10). "Microearthquake seismicity and fault plane solutions related to arc-continent collision in the Eastern Sunda Arc, Indonesia". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 90 (B6): 4511–4528. Bibcode:1985JGR....90.4511M. doi:10.1029/JB090iB06p04511. ISSN 2156-2202.

- "Structure and dynamics of subducted lithosphere in the Mediterranean region". Proceedings of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen. 95 (3). ISSN 0924-8323.

- Chemenda, A. I.; Yang, R. K.; Hsieh, C. -H.; Groholsky, A. L. (1997-06-15). "Evolutionary model for the Taiwan collision based on physical modelling". Tectonophysics. An Introduction to Active Collision in Taiwan. 274 (1): 253–274. Bibcode:1997Tectp.274..253C. doi:10.1016/S0040-1951(97)00025-5.

- Clift, Peter D.; Schouten, Hans; Draut, Amy E. (2003-01-01). "A general model of arc-continent collision and subduction polarity reversal from Taiwan and the Irish Caledonides". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 219 (1): 81–98. Bibcode:2003GSLSP.219...81C. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.219.01.04. ISSN 0305-8719.

- Lallemand, Serge; Font, Yvonne; Bijwaard, Harmen; Kao, Honn (2001-07-10). "New insights on 3-D plates interaction near Taiwan from tomography and tectonic implications". Tectonophysics. 335 (3–4): 229–253. Bibcode:2001Tectp.335..229L. doi:10.1016/S0040-1951(01)00071-3.

- Baes, Marzieh; Govers, Rob; Wortel, Rinus (2011-12-01). "Switching between alternative responses of the lithosphere to continental collision". Geophysical Journal International. 187 (3): 1151–1174. Bibcode:2011GeoJI.187.1151B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2011.05236.x. ISSN 0956-540X.

- Seno, Tetsuzo (1977-10-20). "The instantaneous rotation vector of the Philippine sea plate relative to the Eurasian plate". Tectonophysics. 42 (2): 209–226. Bibcode:1977Tectp..42..209S. doi:10.1016/0040-1951(77)90168-8.

- Vignaroli, Gianluca; Faccenna, Claudio; Jolivet, Laurent; Piromallo, Claudia; Rossetti, Federico (2008-04-01). "Subduction polarity reversal at the junction between the Western Alps and the Northern Apennines, Italy". Tectonophysics. 450 (1–4): 34–50. Bibcode:2008Tectp.450...34V. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2007.12.012.

- Shemenda, Alexander I. (1994-09-30). Subduction: Insights from Physical Modeling. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780792330424.

- Tao, Winston C.; O'connell, Richard J. (1992-06-10). "Ablative subduction: A two-sided alternative to the conventional subduction model". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 97 (B6): 8877–8904. Bibcode:1992JGR....97.8877T. doi:10.1029/91JB02422. ISSN 2156-2202.

- Currie, Claire A.; Hyndman, Roy D. (2006-08-01). "The thermal structure of subduction zone back arcs". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 111 (B8): B08404. Bibcode:2006JGRB..111.8404C. doi:10.1029/2005JB004024. ISSN 2156-2202.

- Currie, C. A; Wang, K; Hyndman, Roy D; He, Jiangheng (2004-06-30). "The thermal effects of steady-state slab-driven mantle flow above a subducting plate: the Cascadia subduction zone and backarc". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 223 (1–2): 35–48. Bibcode:2004E&PSL.223...35C. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2004.04.020.

- Arcay, D.; Doin, M.-P.; Tric, E.; Bousquet, R.; de Capitani, C. (2006-02-01). "Overriding plate thinning in subduction zones: Localized convection induced by slab dehydration". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 7 (2): Q02007. Bibcode:2006GGG.....7.2007A. doi:10.1029/2005GC001061. ISSN 1525-2027.

- Honda, Satoru; Yoshida, Takeyoshi (2005-01-01). "Application of the model of small-scale convection under the island arc to the NE Honshu subduction zone". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 6 (1): Q01002. Bibcode:2005GGG.....6.1002H. doi:10.1029/2004GC000785. ISSN 1525-2027.

- Toth, John; Gurnis, Michael (1998-08-10). "Dynamics of subduction initiation at preexisting fault zones" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 103 (B8): 18053–18067. Bibcode:1998JGR...10318053T. doi:10.1029/98JB01076. ISSN 2156-2202.

- Konstantinovskaia, Elena A (2000-10-15). "Geodynamics of an Early Eocene arc–continent collision reconstructed from the Kamchatka Orogenic Belt, NE Russia". Tectonophysics. 325 (1–2): 87–105. Bibcode:2000Tectp.325...87K. doi:10.1016/S0040-1951(00)00132-3.

- Silver, Eli A.; Reed, Donald; McCaffrey, Robert; Joyodiwiryo, Yoko (1983-09-10). "Back arc thrusting in the Eastern Sunda Arc, Indonesia: A consequence of arc-continent collision". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 88 (B9): 7429–7448. Bibcode:1983JGR....88.7429S. doi:10.1029/JB088iB09p07429.

- Snyder, D. B.; Prasetyo, H.; Blundell, D. J.; Pigram, C. J.; Barber, A. J.; Richardson, A.; Tjokosaproetro, S. (1996-02-01). "A dual doubly vergent orogen in the Banda Arc continent-arc collision zone as observed on deep seismic reflection profiles". Tectonics. 15 (1): 34–53. Bibcode:1996Tecto..15...34S. doi:10.1029/95TC02352. ISSN 1944-9194.

- Angelier, Jacques; Chang, Tsui-Yü; Hu, Jyr-Ching; Chang, Chung-Pai; Siame, Lionel; Lee, Jian-Cheng; Deffontaines, Benoît; Chu, Hao-Tsu; Lu, Chia-Yü (2009-03-10). "Does extrusion occur at both tips of the Taiwan collision belt? Insights from active deformation studies in the Ilan Plain and Pingtung Plain regions". Tectonophysics. Geodynamics and active tectonics in East Asia. 466 (3–4): 356–376. Bibcode:2009Tectp.466..356A. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2007.11.015.

- Leat, P. T.; Larter, R. D. (2003-01-01). "Intra-oceanic subduction systems: introduction". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 219 (1): 1–17. Bibcode:2003GSLSP.219....1L. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.219.01.01. ISSN 0305-8719.

- Van Avendonk, Harm J. A.; McIntosh, Kirk D.; Kuo-Chen, Hao; Lavier, Luc L.; Okaya, David A.; Wu, Francis T.; Wang, Chien-Ying; Lee, Chao-Shing; Liu, Char-Shine (2016-01-01). "A lithospheric profile across northern Taiwan: from arc-continent collision to extension". Geophysical Journal International. 204 (1): 331–346. Bibcode:2016GeoJI.204..331V. doi:10.1093/gji/ggv468. ISSN 0956-540X.

- Suppe, J. (1984). "Kinematics of arc-continent collision, flipping of subduction, and backarc spreading near Taiwan" (PDF). Mem. Geol. Soc. China (6): 21–33.

- Ustaszewski, Kamil; Wu, Yih-Min; Suppe, John; Huang, Hsin-Hua; Chang, Chien-Hsin; Carena, Sara (2012-11-20). "Crust–mantle boundaries in the Taiwan–Luzon arc-continent collision system determined from local earthquake tomography and 1D models: Implications for the mode of subduction polarity reversal". Tectonophysics. Geodynamics and Environment in East Asia. 578: 31–49. Bibcode:2012Tectp.578...31U. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2011.12.029.