Volcanic arc

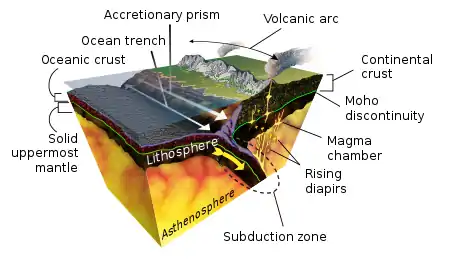

A volcanic arc is a chain of volcanoes formed above a subducting plate,[1] positioned in an arc shape as seen from above. Offshore volcanoes form islands, resulting in a volcanic island arc. Generally, volcanic arcs result from the subduction of an oceanic tectonic plate under another tectonic plate, and often parallel an oceanic trench. The oceanic plate is saturated with water, and volatiles such as water drastically lower the melting point of the mantle. As the oceanic plate is subducted, it is subjected to greater and greater pressures with increasing depth. This pressure squeezes water out of the plate and introduces it to the mantle. Here the mantle melts and forms magma at depth under the overriding plate. The magma ascends to form an arc of volcanoes parallel to the subduction zone.

These should not be confused with hotspot volcanic chains, where volcanoes often form one after another in the middle of a tectonic plate, as the plate moves over the hotspot, and so the volcanoes progress in age from one end of the chain to the other. The Hawaiian Islands form a typical hotspot chain; the older islands (tens of millions of years old) to the northwest are smaller and have more soil than the recently created (400,000 years ago) Hawaii island itself, which is more rocky. Hotspot volcanoes are also known as "intra-plate" volcanoes, and the islands they create are known as Volcanic Ocean Islands. Volcanic arcs do not generally exhibit such a simple age-pattern.

There are two types of volcanic arcs:

- oceanic arcs form when oceanic crust subducts beneath other oceanic crust on an adjacent plate, creating a volcanic island arc. (Not all island arcs are volcanic island arcs.)

- continental arcs form when oceanic crust subducts beneath continental crust on an adjacent plate, creating an arc-shaped mountain belt.

In some situations, a single subduction zone may show both aspects along its length, as part of a plate subducts beneath a continent and part beneath adjacent oceanic crust.

Volcanoes are present in almost any mountain belt, but this does not make it a volcanic arc. Often there are isolated, but impressively huge volcanoes in a mountain belt. For instance, Vesuvius and the Etna volcanoes in Italy are part of separate but different kinds of mountainous volcanic ensembles.

The active front of a volcanic arc is the belt where volcanism develops at a given time. Active fronts may move over time (millions of years), changing their distance from the oceanic trench as well as their width.

Petrology

In a subduction zone, loss of water from the subducted slab induces partial melting of the overriding mantle and generates low-density, calc-alkaline magma that buoyantly rises to intrude and be extruded through the lithosphere of the overriding plate. This loss of water is due to the destabilization of the mineral chlorite at approximately 40–60 km depth.[2][3] This is the reason for island arc volcanism at consistent distances from the subducting slab: because the temperature-pressure conditions for flux-melting volcanism due to chlorite destabilization will always occur at the same depth, the distance from the trench to the arc volcanoes is determined only by the dip angle of the subducting slab.

On the subducting side of the arc is a deep and narrow oceanic trench, which is the trace at the Earth's surface of the boundary between the down-going and overriding plates. This trench is created by the gravitational pull of the relatively dense subducting plate pulling the leading edge of the plate downward. Multiple earthquakes occur along this subduction boundary with the seismic hypocenters located at increasing depth under the island arc: these quakes define the Wadati–Benioff zones. The volcanic arc forms when the subducting plate reaches a depth of about 100 kilometres (62 mi).

Ocean basins that are being reduced by subduction are called 'remnant oceans' as they will slowly be shrunken out of existence and crushed in the subsequent orogenic collision. This process has happened over and over in the geologic history of the Earth.

In the rock record, volcanic arcs can be seen as the volcanic rocks themselves, but because volcanic rock is easily weathered and eroded, it is more typical that they are seen as plutonic rocks, the rocks that formed underneath the arc (e.g. the Sierra Nevada batholith), or in the sedimentary record as lithic sandstones.

Examples

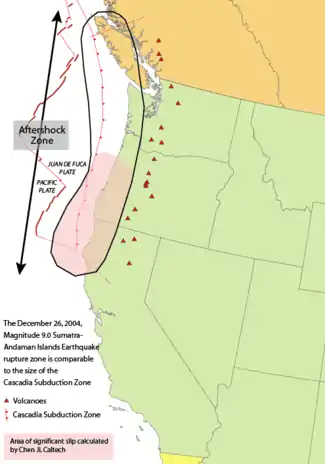

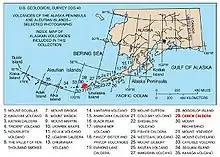

Two classic examples of oceanic island arcs are the Mariana Islands in the western Pacific Ocean and the Lesser Antilles in the western Atlantic Ocean. The Cascade Volcanic Arc in western North America and the Andes along the western edge of South America are examples of continental volcanic arcs. The best examples of volcanic arcs with both sets of characteristics are in the North Pacific, with the Aleutian Arc consisting of the Aleutian Islands and their extension the Aleutian Range on the Alaska Peninsula, and the Kuril-Kamchatka Arc comprising the Kuril Islands and southern Kamchatka Peninsula.

Cascade Volcanic Arc, a continental volcanic arc

Cascade Volcanic Arc, a continental volcanic arc The Aleutian Arc, with both oceanic and continental parts.

The Aleutian Arc, with both oceanic and continental parts.

Continental arcs

Island arcs

- Aleutian Islands

- Kuril Islands

- Northeastern Japan Arc

- Japanese Archipelago including the Ryukyu Islands

- Izu-Bonin-Mariana Arc:

- Luzon Volcanic Arc

- Philippines

- Tonga and Kermadec Islands

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands

- Mentawai Islands

- Sunda Arc

- Tanimbar and Kai Islands

- Solomon Islands

- South Aegean Volcanic Arc

- Egean, or Hellenic arc

- Lesser Antilles, including the Leeward Antilles

- Scotia Arc:

- Mascarene Islands

Ancient island arcs

References

- "Volcanic arc definition from the Dictionary of Geology". Retrieved 2014-11-01.

- Grove, T. L., N. Chatterjee, S. W. Parman, and E. Médard (2006), The Influence of H2O on Mantle Wedge Melting, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 249, 74–89.

- Grove, T.L., C. B. Till, N. Chatterjee, and E. Médard (submitted 2008), Transport of H2O in subduction zones and its role in the formation and location of arc volcanoes, Nature.