Subtle body

A subtle body (Sanskrit: सूक्ष्म शरीर, IAST:sūkṣma śarīra) is one of a series of psycho-spiritual constituents of living beings, according to various esoteric, occult, and mystical teachings. According to such beliefs each subtle body corresponds to a subtle plane of existence, in a hierarchy or great chain of being that culminates in the physical form.

.jpg.webp)

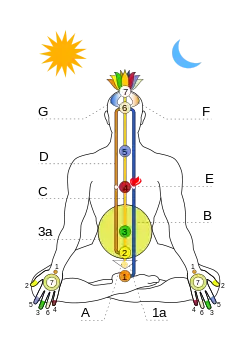

The subtle body consists of focal points, often called chakras, connected by channels, often called nadis, that convey subtle breath (with names such as prana or vayu). These are understood to determine the characteristics of the physical body. Through breathing and other exercises, a practitioner may direct the subtle breath to achieve supernormal powers, immortality, or liberation.

The subtle body (Sanskrit: sūkṣma śarīra) is important in Indian religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, mainly in the forms which focus on tantra and yoga. Other spiritual traditions teach about a mystical or divine body.

Asian religions

The Yogic, Tantric and other systems of Hinduism, Vajrayana Buddhism, as well as Chinese Taoist alchemy contain theories of subtle physiology with focal points (chakras, acupuncture points) connected by a series of channels (nadis, meridians) that convey subtle breath (prana, vayu, ch'i, ki, lung). These invisible channels and points are understood to determine the characteristics of the visible physical form. By understanding and mastering the subtlest levels of reality one gains mastery over the physical realm. Through breathing and other exercises, the practitioner aims to manipulate and direct the flow of subtle breath, to achieve supernormal powers (siddhis) and attain higher states of consciousness, immortality, or liberation.[1][2]

Hinduism

Early

Early concepts of the subtle body (Sanskrit: sūkṣma śarīra) appeared in the Upanishads, including the Brhadaranyaka Upanishad and the Katha Upanishad.[3] The Taittiriya Upanishad describes the theory of five koshas or sheaths, though these are not to be thought of as concentric layers, but interpenetrating at successive levels of subtlety:[4][5]

- The anna-maya ("food body", physical body, the grossest level),

- The prana-maya (body made of vital breath or prana),

- The mano-maya (body made of mind),

- The vijñana-maya (body made of consciousness)

- The ananda-maya (bliss body, the subtlest level).

Subtle internal anatomy included a central channel (nadi).[4] In later Vedic texts called samhitas and brahmanas one also finds a theory of five "winds" or "breaths" (vayus, pranas):[4]

- Prāṇa, associated with inhalation

- Apāna, associated with exhalation

- Uḍāna, associated with distribution of breath within the body

- Samāna, associated with digestion

- Vyāna, associated with excretion of waste

Later

A millennium later, these concepts were adapted and refined by various spiritual traditions. The similar concept of the Liṅga Śarīra is seen as the vehicle of consciousness in later Samkhya, Vedanta, and Yoga, and is propelled by past-life tendencies, or bhavas.[6] Linga can be translated as "characteristic mark" or "impermanence" and the Vedanta term sarira as "form" or "mold".[7] Karana or "instrument" is a synonymous term. In the Classical Samkhya system of Isvarakrsna (ca. 4th century CE), the Lińga is the characteristic mark of the transmigrating entity. It consists of twenty-five tattvas from eternal consciousness down to the five organs of sense, five of activity (buddindriya or jñānendriya, and karmendriya respectively) and the five subtle elements that are the objects of sense (tanmatras) The Samkhyakarika says:[8]

The subtle body (linga), previously arisen, unconfined, constant, inclusive of the great one (mahat) etc, through the subtle elements, not having enjoyment, transmigrates, (because of) being endowed with bhavas ("conditions" or "dispositions"). As a picture (does) not (exist) without a support, or as a shadow (does) not (exist) without a post and so forth; so too the instrument (linga or karana) does not exist without that which is specific (i.e. a subtle body).

— Samkhyakarika, 60-81[8]

The classical Vedanta tradition developed the theory of the five bodies into the theory of the koshas "sheaths" or "coverings" which surround and obscure the self (atman). In classical Vedanta these are seen as obstacles to realization and traditions like Shankara's Advaita Vedanta had little interest in working with the subtle body.[9]

Tantra

In Tantra traditions meanwhile (Shaiva Kaula, Kashmir Shaivism and Buddhist Vajrayana), the subtle body was seen in a more positive light, offering potential for yogic practices which could lead to liberation.[10] Tantric traditions contain the most complex theories of the subtle body, with sophisticated descriptions of energy nadis (literally "stream or river", channels through which vayu and prana flows) and chakras, points of focus where nadis meet.[11]

The main channels, shared by both Hindu and Buddhist systems, but visualised entirely differently, are the central (in Hindu systems: sushumna; in Buddhist: avadhuti), left and right (in Hindu systems: ida and pingala; Buddhist: lalana and rasana).[12] Further subsidiary channels are said to radiate outwards from the chakras, where the main channels meet.[13]

Chakra systems vary with the tantra; the Netra Tantra describes six chakras, the Kaulajñana-nirnaya describes eight, and the Kubjikamata Tantra describes seven (the most widely known set).[14][15]

Modern

The modern Indian spiritual teacher Meher Baba stated that the subtle body "is the vehicle of desires and vital forces". He held that the subtle body is one of three bodies with which the soul must cease to identify in order to realize God.[16]

Buddhism

.jpg.webp)

In Buddhist Tantra, the subtle body is termed the ‘innate body’ (nija-deha) or the ‘uncommon means body’ (asadhdrana-upayadeha).[17] It is also called sūkṣma śarīra, rendered in Tibetan as traway-lu (transliterated phra ba’i lus).[18]

The subtle body consists of thousands of subtle energy channels (nadis), which are conduits for energies or "winds" (lung or prana) and converge at chakras.[17] According to Dagsay Tulku Rinpoche, there are three main channels (nadis), central, left and right, which run from the point between the eyebrows up to the crown chakra, and down through all seven chakras to a point two inches below the navel.[19]

Buddhist tantras generally describe four or five chakras in the shape of a lotus with varying petals. For example, the Hevajra Tantra (8th century) states:

In the Center [i.e. chakra] of Creation [at the sexual organ] a sixty-four petal lotus. In the Center of Essential Nature [at the heart] an eight petal lotus. In the Center of Enjoyment [at the throat] a sixteen petal lotus. In the Center of Great Bliss [at the top of the head] a thirty-two petal lotus.[14]

In contrast, the historically later Kalachakra tantra describes six chakras.[14]

In Vajrayana Buddhism, liberation is achieved through subtle body processes during Completion Stage practices such as the Six Yogas of Naropa.[20]

Other traditions

Other spiritual traditions teach about a mystical or divine body, such as "the most sacred body" (wujud al-aqdas) and "true and genuine body" (jism asli haqiqi) in Sufism, the meridian system in Chinese religion, and "the immortal body" (soma athanaton) in Hermeticism.[21]

Western esotericism

Theosophy

In the 19th century, H. P. Blavatsky founded the esoteric religious system of Theosophy, which attempted to restate Hindu and Buddhist philosophy for the Western world.[22] She adopted the phrase "subtle body" as the English equivalent of the Vedantic sūkṣmaśarīra, which in Adi Shankara's writings was one of three bodies (physical, subtle, and causal). Geoffrey Samuel notes that theosophical use of these terms by Blavatsky and later authors, especially C. W. Leadbeater, Annie Besant and Rudolf Steiner (who went on to found Anthroposophy), has made them "problematic"[22] to modern scholars, since the Theosophists adapted the terms as they expanded their ideas based on "psychic and clairvoyant insights", changing their meaning from what they had in their original context in India.[22] [22]

Post-theosophists

The later theosophical arrangement was taken up by Alice Bailey, and from there found its way into the New Age worldview[23] and the human aura.[24]

Max Heindel divided the subtle body into the Vital Body made of Ether; the Desire body, related to the Astral plane; and the Mental body.[25]

Samael Aun Weor wrote extensively on the subtle bodies (Astral, Mental, and Causal), aligning them with the kabbalistic tree of life.[26]

Barbara Brennan's account of the subtle bodies in her books Hands of Light and Light Emerging refers to the subtle bodies as "layers" in the "Human Energy Field" or aura.[27]

Fourth Way

Subtle bodies are found in the "Fourth Way" teachings of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, which claim that one can create a subtle body, and hence achieve post-mortem immortality, through spiritual or yogic exercises. The "soul" in these systems is not something one is born with, but developed through esoteric practice to acquire complete understanding and to perfect the self. According to the historian Bernice Rosenthal, "In Gurdjieff's cosmology our nature is tripartite and is composed of the physical (planetary), emotional (astral) and mental (spiritual) bodies; in each person one of these three bodies ultimately achieves dominance."[28] The ultimate task of the fourth way teachings is to harmoniously develop the four bodies into a single way.[28]

Aleister Crowley

The occultist Aleister Crowley's system of magick envisaged "a subtle body (instrument is a better term) called the Body of Light; this one develops and controls; it gains new powers as one progresses".[29]

References

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 171–184.

- Pregadio, Fabrizio (2012). The Way of the Golden Elixir: A Historical Overview of Taoist Alchemy (PDF, 60 pp., free download). Golden Elixir Press.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 173-174.

- Samuel 2013, p. 33.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 184.

- Larson 2005, p. 242.

- Purucker, Gottfried. The Occult Glossary

- Larson 2005, p. 268.

- Samuel 2013, pp. 34, 37.

- Samuel 2013, p. 34.

- Samuel 2013, p. 38-39.

- Samuel 2013, p. 39.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 172-174.

- Samuel 2013, p. 40.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 175-178.

- Baba, Meher (1967). Discourses, volume 2. San Francisco: Sufism Reoriented. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-1880619094.

- Wayman, Alex (1977). Yoga of the Guhyasamajatantra: The arcane lore of forty verses : a Buddhist Tantra commentary. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 65.

- Miller, Lama Willa B. "Reviews: Investigating the Subtle Body". Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Dagsay Tulku Rinpoche (2002). The Practice of Tibetan Meditation: Exercises, Visualizations, and Mantras for Health and Well-being. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 80. ISBN 978-0892819034.

- Samuel 2013, p. 38.

- White.

- Samuel 2013, pp. 1-3.

- Johnston, Jay (2002). "The "Theosophic Glance": Fluid Ontologies, Subtle Bodies and Intuitive Vision". Australian Religion Studies Review. 15 (2): 101–117.

- Hammer, Olav (2001). Claiming Knowledge: Strategies of Epistemology from Theosophy to the New Age. Brill. p. 55. ISBN 900413638X.

- Heindel, Max (1911). The Rosicrucian Mysteries. p. Chapter IV, The Constitution of Man: Vital Body - Desire Body - Mind. ISBN 0-911274-86-3.

- Samael Aun Weor. "Types of Spiritual Schools". Archived from the original on 31 May 2007.

- Dale, Cyndi. "Energetic Anatomy: A Complete Guide to the Human Energy Fields and Etheric Bodies". Conscious Lifestyle magazine. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- Rosenthal, Bernice (1997). The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture. Cornell University Press. p. 361. ISBN 978-0-8014-8331-8. OCLC 35990156.

- Aleister Crowley Magick (Book 4), chapter 81.

Sources

- Larson, Gerald James (2005). Classical Samkhya : an interpretation of its history and meaning. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0503-3. OCLC 637247445.

- Mallinson, James & Singleton, Mark (2017). Roots of Yoga. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-25304-5. OCLC 928480104.

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2013). Religion and the subtle body in Asia and the West : between mind and body. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-60811-4. OCLC 690084604.

Further reading

- Alfass, Mirra (The Mother) Mother's Agenda

- Besant, Annie, Man and His Bodies

- Brennan, Barbara Ann, Hands of Light : A Guide to Healing Through the Human Energy Field, Bantam Books, 1987

- —, Light Emerging: The Journey of Personal Healing, Bantam Books, 1993

- Eliade, Mircea, Yoga: Immortality and Freedom; transl. by W.R. Trask, Princeton University Press, 1969

- C. W. Leadbeater, Man, Visible and Invisible

- Sheila Ostrander and Lynn Schroeder Psychic Discoveries Behind the Iron Curtain, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1970.

- Poortman, J. J. Vehicles of Consciousness; The Concept of Hylic Pluralism (Ochema), vol I-IV, The Theosophical Society in Netherlands, 1978

- Powell, Arthur E. The Astral Body and other Astral Phenomena

- —, The Causal Body and the Ego

- —, The Etheric Double

- —, The Mental Body

- Samael Aun Weor, The Perfect Matrimony or The Door to Enter into Initiation. Thelema Press. (1950) 2003.

- Samael Aun Weor, The Esoteric Course of Alchemical Kabbalah. Thelema Press. (1969) 2007.

- Steiner, Rudolf, Theosophy: An introduction to the supersensible knowledge of the world and the destination of man. London: Rudolf Steiner Press. (1904) 1970

- —, Occult science – An Outline. Trans. George and Mary Adams. London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1909, 1969

- Heindel, Max, The Rosicrucian Mysteries (Chapter IV: The Constitution of Man: Vital Body - Desire Body - Mind), 1911, ISBN 0-911274-86-3

- Crowley, Aleister (1997). Magick (Book 4) 2nd ed. York Beach, Maine. : Samuel Weiser.

- —, (1982). Magick Without Tears. Phoenix, AZ : Falcon Press

- Thelemapedia. (2004). Body of Light.

- White, John. Enlightenment and the Body of Light in What Is Enlightenment? magazine.

- Oschman, James L. Energy Medicine: The Scientific Basis.

- Levin, Michal. Meditation, Path to the Deepest Self, Dorling Kindersley, 2002. ISBN 978-0789483331

- Levin, Michal. Spiritual Intelligence: Awakening the Power of Your Spirituality and Intuition. Hodder & Stoughton, 2000. ISBN 978-0340733943

- Paramahansa Yogananda, Autobiography of a Yogi, Los Angeles, CA: Self-Realization Fellowship, 1946, Chapter 43.