Ashtanga (eight limbs of yoga)

Ashtanga yoga (Sanskrit: aṣṭāṅgayoga[1], "the eight limbs of yoga") is Patanjali's classification of classical yoga, as set out in his Yoga Sutras. He defined the eight limbs as yama (abstinences), niyama (observances), asana (postures), pranayama (breathing), pratyahara (withdrawal), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation) and samadhi (absorption).

The eight limbs form a sequence from the outer to the inner. Postures, important in modern yoga as exercise, form one limb of Patanjali's scheme; he states only that they must be steady and comfortable.

Eight limbs

Patanjali set out his definition of yoga in the Yoga Sutras as having eight limbs (अष्टाङ्ग aṣṭ āṅga, "eight limbs") as follows:

The eight limbs of yoga are yama (abstinences), niyama (observances), asana (yoga postures), pranayama (breath control), pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation) and samadhi (absorption)."[2]

The eightfold path of Patanjali's yoga consists of a set of prescriptions for a morally disciplined and purposeful life, of which asanas (yoga postures) form only one limb.[3]

1. Yamas

Yamas are ethical rules in Hinduism and can be thought of as moral imperatives (the "don'ts"). The five yamas listed by Patanjali in Yoga Sutra 2.30 are:[4]

- Ahimsa (अहिंसा): Nonviolence, non-harming other living beings[5]

- Satya (सत्य): truthfulness, non-falsehood[5][6]

- Asteya (अस्तेय): non-stealing[5]

- Brahmacharya (ब्रह्मचर्य): chastity,[6] marital fidelity or sexual restraint[7]

- Aparigraha (अपरिग्रह): non-avarice,[5] non-possessiveness[6]

Patanjali, in Book 2, states how and why each of the above self-restraints help in an individual's personal growth. For example, in verse II.35, Patanjali states that the virtue of nonviolence and non-injury to others (Ahimsa) leads to the abandonment of enmity, a state that leads the yogi to the perfection of inner and outer amity with everyone, everything.[8][9]

2. Niyamas

The second component of Patanjali's Yoga path is niyama, which includes virtuous habits and observances (the "dos").[10][11] Sadhana Pada Verse 32 lists the niyamas as:[12]

- Shaucha (शौच): purity, clearness of mind, speech and body[13]

- Santosha (संतोष): contentment, acceptance of others, acceptance of one's circumstances as they are in order to get past or change them, optimism for self[14]

- Tapas (तपस्): persistence, perseverance, austerity, asceticism, self-discipline[15][16][17][18]

- Svadhyaya (स्वाध्याय): study of Vedas, study of self, self-reflection, introspection of self's thoughts, speech and actions[16][19]

- Ishvarapranidhana (ईश्वरप्रणिधान): contemplation of the Ishvara (God/Supreme Being, Brahman, True Self, Unchanging Reality)[14][20]

As with the Yamas, Patanjali explains how and why each of the Niyamas help in personal growth. For example, in verse II.42, Patanjali states that the virtue of contentment and acceptance of others as they are (Santosha) leads to the state where inner sources of joy matter most, and the craving for external sources of pleasure ceases.[21]

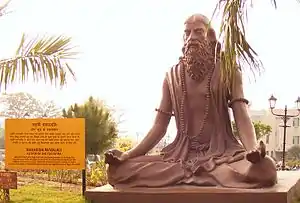

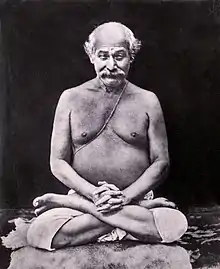

3. Āsana

Patanjali begins discussion of Āsana (आसन, posture, seat) by defining it in verse 46 of Book 2, as follows,[22]

स्थिरसुखमासनम् ॥४६॥

The meditation posture should be steady and comfortable.[23][24]— Yoga Sutras II.46

Asana is a posture that one can hold for a period of time, staying relaxed, steady, comfortable and motionless. The Yoga Sutra does not list any specific asana.[25] Āraṇya translates verse II.47 of Yoga sutra as, "asanas are perfected over time by relaxation of effort with meditation on the infinite"; this combination and practice stops the quivering of body.[26] Any posture that causes pain or restlessness is not a yogic posture. Secondary texts that discuss Patanjali's sutra state that one requirement of correct posture for sitting meditation is to keep chest, neck and head erect (proper spinal posture).[24]

The Bhasya commentary attached to the Sutras, now thought to be by Patanjali himself,[27] suggests twelve seated meditation postures:[28] Padmasana (lotus), Virasana (hero), Bhadrasana (glorious), Svastikasana (lucky mark), Dandasana (staff), Sopasrayasana (supported), Paryankasana (bedstead), Krauncha-nishadasana (seated heron), Hastanishadasana (seated elephant), Ushtranishadasana (seated camel), Samasansthanasana (evenly balanced) and Sthirasukhasana (any motionless posture that is in accordance with one's pleasure).[24]

Over a thousand years later, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika mentions 84 [lower-alpha 1] asanas taught by Shiva, stating four of these as most important: Siddhasana (accomplished), Padmasana (lotus), Simhasana (lion), and Bhadrasana (glorious), and describes the technique of these four and eleven other asanas.[30][31] In modern yoga, asanas are prominent and numerous, unlike in any earlier form of yoga.[32][33]

4. Prānāyāma

Prāṇāyāma is the control of the breath, from the Sanskrit prāṇa (प्राण, breath)[34] and āyāma (आयाम, restraint).[35]

After a desired posture has been achieved, verses II.49 through II.51 recommend prāṇāyāma, the practice of consciously regulating the breath (inhalation, the full pause, exhalation, and the empty pause).[36] This is done in several ways, such as by inhaling and then suspending exhalation for a period, exhaling and then suspending inhalation for a period, by slowing the inhalation and exhalation, or by consciously changing the timing and length of the breath (deep, short breathing).[37][38]

5. Pratyāhāra

Pratyāhāra is a combination of two Sanskrit words prati- (the prefix प्रति-, "against" or "contra") and āhāra (आहार, "bring near, fetch").[39]

Pratyahara is drawing within one's awareness. It is a process of retracting the sensory experience from external objects. It is a step of self extraction and abstraction. Pratyahara is not consciously closing one's eyes to the sensory world, it is consciously closing one's mind processes to the sensory world. Pratyahara empowers one to stop being controlled by the external world, fetch one's attention to seek self-knowledge and experience the freedom innate in one's inner world.[40][41]

Pratyahara marks the transition of yoga experience from the first four limbs of Patanjali's Ashtanga scheme that perfect external forms, to the last three limbs that perfect the yogin's inner state: moving from outside to inside, from the outer sphere of the body to the inner sphere of the spirit.[42]

6. Dhāraṇā

Dharana (Sanskrit: धारणा) means concentration, introspective focus and one-pointedness of mind. The root of the word is dhṛ (धृ), meaning "to hold, maintain, keep".[43]

Dharana, as the sixth limb of yoga, is holding one's mind onto a particular inner state, subject or topic of one's mind.[44] The mind is fixed on a mantra, or one's breath/navel/tip of tongue/any place, or an object one wants to observe, or a concept/idea in one's mind.[45][46] Fixing the mind means one-pointed focus, without drifting of mind, and without jumping from one topic to another.[45]

7. Dhyāna

Dhyana (Sanskrit: ध्यान) literally means "contemplation, reflection" and "profound, abstract meditation".[47]

Dhyana is contemplating, reflecting on whatever Dharana has focused on. If in the sixth limb of yoga one focused on a personal deity, Dhyana is its contemplation. If the concentration was on one object, Dhyana is non-judgmental, non-presumptuous observation of that object.[48] If the focus was on a concept/idea, Dhyana is contemplating that concept/idea in all its aspects, forms and consequences. Dhyana is uninterrupted train of thought, current of cognition, flow of awareness.[46]

Dhyana is integrally related to Dharana, one leads to other. Dharana is a state of mind, Dhyana the process of mind. Dhyana is distinct from Dharana in that the meditator becomes actively engaged with its focus. Patanjali defines contemplation (Dhyana) as the mind process, where the mind is fixed on something, and then there is "a course of uniform modification of knowledge".[49] Adi Shankara, in his commentary on Yoga Sutras, distinguishes Dhyana from Dharana, by explaining Dhyana as the yoga state when there is only the "stream of continuous thought about the object, uninterrupted by other thoughts of different kind for the same object"; Dharana, states Shankara, is focussed on one object, but aware of its many aspects and ideas about the same object. Shankara gives the example of a yogin in a state of dharana on morning sun may be aware of its brilliance, color and orbit; the yogin in dhyana state contemplates on sun's orbit alone for example, without being interrupted by its color, brilliance or other related ideas.[50]

8. Samādhi

Samadhi (Sanskrit: समाधि) literally means "putting together, joining, combining with, union, harmonious whole, trance".[51][52]

Samadhi is oneness with the subject of meditation. There is no distinction, during the eighth limb of yoga, between the actor of meditation, the act of meditation and the subject of meditation. Samadhi is that spiritual state when one's mind is so absorbed in whatever it is contemplating on, that the mind loses the sense of its own identity. The thinker, the thought process and the thought fuse with the subject of thought. There is only oneness, samadhi.[46][53][54]

See also

- Seven stages (Yogi) — the seven stages of progress in the Vyasa commentary on the Yoga Sutras

Notes

- 84's symbolism may derive from its astrological and numerological properties: it is the product of 7, the number of planets in astrology, and 12, the number of signs of the zodiac, while in numerology, 7 is the sum of 3 and 4, and 12 is the product, i.e. 84 is (3+4)×(3×4).[29]

References

- Huet, Gérard. "Sanskrit Heritage Dictionary". sanskrit.inria.fr. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Yoga Sutras 2.29.

- Carrico, Mara (10 July 2017). "Get to Know the Eight Limbs of Yoga". Yoga Journal.

- Āgāśe, K. S. (1904). Pātañjalayogasūtrāṇi. Puṇe: Ānandāśrama. p. 102.

- James Lochtefeld, "Yama (2)", The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N–Z, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 9780823931798, page 777

- Arti Dhand (2002), The dharma of ethics, the ethics of dharma: Quizzing the ideals of Hinduism, Journal of Religious Ethics, 30(3), pages 347-372

- [a] Louise Taylor (2001), A Woman's Book of Yoga, Tuttle, ISBN 978-0804818292, page 3;

[b]Jeffrey Long (2009), Jainism: An Introduction, IB Tauris, ISBN 978-1845116262, page 109; Quote: The fourth vow - brahmacarya - means for laypersons, marital fidelity and pre-marital celibacy; for ascetics, it means absolute celibacy; John Cort states, "Brahmacharya involves having sex only with one's spouse, as well as the avoidance of ardent gazing or lewd gestures (...) - Quoted by Long, ibid, page 101 - The Yoga Philosophy T. R. Tatya (Translator), with Bhojaraja commentary; Harvard University Archives, page 80

- Jan E. M. Houben and Karel Rijk van Kooij (1999), Violence Denied: Violence, Non-Violence and the Rationalization of Violence in South Asian Cultural History, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004113442, page 5

- N. Tummers (2009), Teaching Yoga for Life, ISBN 978-0736070164, page 13-16

- Y. Sawai (1987), "The Nature of Faith in the Śaṅkaran Vedānta Tradition", Numen, Vol. 34, Fasc. 1 (Jun., 1987), pages 18-44

- Āgāśe, K. S. (1904). Pātañjalayogasūtrāṇi. Puṇe: Ānandāśrama. p. 102.

- Sharma and Sharma, Indian Political Thought, Atlantic Publishers, ISBN 978-8171566785, page 19

- N Tummers (2009), Teaching Yoga for Life, ISBN 978-0736070164, page 16-17

- Kaelber, W. O. (1976). "Tapas", Birth, and Spiritual Rebirth in the Veda, History of Religions, 15(4), 343-386

- SA Bhagwat (2008), Yoga and Sustainability. Journal of Yoga, Fall/Winter 2008, 7(1): 1-14

- Espín, Orlando O.; Nickoloff, James B. (2007). An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies. Liturgical Press. p. 1356. ISBN 978-0-8146-5856-7.

- Robin Rinehart (2004). Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice. ABC-CLIO. p. 359. ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8.

- Polishing the mirror Yoga Journal, Gary Kraftsow, February 25, 2008

- Īśvara + praṇidhāna, Īśvara Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine and praṇidhāna Archived 2016-04-16 at the Wayback Machine, Spoken Sanskrit.

- The Yoga Philosophy T. R. Tatya (Translator), with Bhojaraja commentary; Harvard University Archives, page 84

- The Yoga Philosophy TR Tatya (Translator), with Bhojaraja commentary; Harvard University Archives; The Yoga-darsana: The sutras of Patanjali with the Bhasya of Vyasa GN Jha (Translator), with notes; Harvard University Archives; The Yogasutras of Patanjali Charles Johnston (Translator)

- The Yoga Philosophy T. R. Tatya (Translator), with Bhojaraja commentary; Harvard University Archives, page 86

- Hariharānanda Āraṇya (1983), Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0873957281, page 228 with footnotes

- The Yoga-darsana: The sutras of Patanjali with the Bhasya of Vyasa GN Jha (Translator); Harvard University Archives, page xii

- Hariharānanda Āraṇya (1983), Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0873957281, page 229

- Maas, Philipp A. (2013). A Concise Historiography of Classical Yoga Philosophy, in: Eli Franco (ed.), Periodization and Historiography of Indian Philosophy. Vienna: Sammlung de Nobili, Institut für Südasien-, Tibet- und Buddhismuskunde der Universität Wien.

- The Yoga-darsana: The sutras of Patanjali with the Bhasya of Vyasa G. N. Jha (Translator); Harvard University Archives, page 89

- Rosen, Richard (2017). Yoga FAQ: Almost Everything You Need to Know about Yoga-from Asanas to Yamas. Shambhala. pp. 171–. ISBN 978-0-8348-4057-7.

this number has symbolic significance. S. Dasgupta, in Obscure Religious Cults (1946), cites numerous instances of variations on eighty-four in Indian literature that stress its 'purely mystical nature'; ... Gudrun Bühnemann, in her comprehensive Eighty-Four Asanas in Yoga, notes that the number 'signifies completeness, and in some cases, sacredness. ... John Campbell Oman, in The Mystics, Ascetics, and Saints of India (1905) ... seven ... classical planets in Indian astrology ... and twelve, the number of signs of the zodiac. ... Matthew Kapstein gives .. a numerological point of view ... 3+4=7 ... 3x4=12 ...

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika P Sinh (Translator), pages 33-35

- Mikel Burley (2000), Haṭha-Yoga: Its Context, Theory, and Practice, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120817067, page 198

- Singleton, Mark (4 February 2011). "The Ancient & Modern Roots of Yoga". Yoga Journal.

- Jain, Andrea (July 2016). "The Early History of Modern Yoga". Oxford Research Encyclopedias. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.163. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- prAna Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

- AyAma Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

- Hariharānanda Āraṇya (1983), Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0873957281, pages 230-236

- The Yoga Philosophy TR Tatya (Translator), with Bhojaraja commentary; Harvard University Archives, page 88-91

- The Yoga-darsana: The sutras of Patanjali with the Bhasya of Vyasa GN Jha (Translator); Harvard University Archives, pages 90-91

- AhAra Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

- GS Iyengar (1998), Yoga: A Gem for Women, ISBN 978-8170237150, pages 29-30

- Charlotte Bell (2007), Mindful Yoga, Mindful Life: A Guide for Everyday Practice, Rodmell Press, ISBN 978-1930485204, pages 136-144

- R. S. Bajpai (2002), The Splendours And Dimensions Of Yoga, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8171569649, pages 342-345

- dhR, Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary (2008 revision), Cologne Digital Sanskrit Lexicon, Germany

- Bernard Bouanchaud (1997), The Essence of Yoga: Reflections on the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, Rudra Press, ISBN 9780915801695, page 149

- Charlotte Bell (2007), Mindful Yoga, Mindful Life: A Guide for Everyday Practice, Rodmell Press, ISBN 978-1930485204, pages 145-151

- The Yoga-darsana: The sutras of Patanjali with the Bhasya of Vyasa - Book 3 GN Jha (Translator); Harvard University Archives, pages 94-95

- dhyAna, Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary (2008 revision), Cologne Digital Sanskrit Lexicon, Germany

- Charlotte Bell (2007), Mindful Yoga, Mindful Life: A Guide for Everyday Practice, Rodmell Press, ISBN 978-1930485204, pages 151-159

- The Yoga Philosophy TR Tatya (Translator), with Bhojaraja commentary; Harvard University Archives, page 94-95

- Trevor Leggett (1983), Shankara on the Yoga Sutras, Volume 2, Routledge, ISBN 978-0710095398, pages 283-284

- samAdhi, Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary (2008 revision), Cologne Digital Sanskrit Lexicon, Germany

- samAdhi Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

- Hariharānanda Āraṇya (1983), Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0873957281, pages 252-253

- Michele Marie Desmarais (2008), Changing Minds : Mind, Consciousness And Identity In Patanjali'S Yoga-Sutra, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120833364, pages 175-176