SweeTango

SweeTango is the brand designation of the cultivated apple 'Minneiska'. It is a patented cross breed between the 'Honeycrisp' and the Zestar! apple. The trademark name belongs to the University of Minnesota. The apple is a controlled and regulated product for marketing to the public. The apple is controlled and regulated for marketing, allowing only exclusive territories for growing. It has a sweet-tart taste that some food writers have described as something between brown sugar and spiced apple cider.

| |

| Hybrid parentage | Honeycrisp and Zestar Apple |

|---|---|

| Cultivar | Minneiska |

| Origin | University of Minnesota, United States |

University of Minnesota awarded Pepin Heights Orchards exclusive marketing rights to grow and sell the 'Minneiska' apple. They then in turn developed a cooperative of certain selected farm growers and sold rights to these members to produce the apple. It was exclusive at first to the state of Minnesota and later membership was expanded to certain qualifying farmers, mostly to growers of the northern parts of the United States. The concept of exclusive control of a variety of fruit was new then in United States customs and drew criticism that led to lawsuits.

Background

The brand name of the cultivar (cultivated variety) of the apple 'Minneiska' is "SweeTango".[1][2] It was refined by University of Minnesota in 1999 from a grafted tree of 1988. It was released in 2006[3] and officially available to the public in 2007.[4] The apple first sold in eastern United States in 2009.[5] It is a hybrid of two other apple varieties the university developed: the 'Honeycrisp' and the 'Minnewashta' (brand name Zestar!).[6][7] In apple breeding horticultural terminology the 'Honeycrisp' is the bride and the Zestar is the groom.[8] The offspring of the two is the fruit product of the 'Minneiska' tree.[8]

The name is a registered trademark owned by University of Minnesota. In 2000, the new apple variety was known during development by the identifier MN 1914.[1] It was created by University of Minnesota's plant development program at their Horticultural Research Center's 80-acre (32 ha) farm near Victoria, Minnesota.[9]

Agriculture

The apple is an early fruit with a seasonal harvest starting in late August. It ripens about the first week of September in Excelsior, Minnesota. Ripening time is slightly after 'Minnewashta' (Zestar!), and about two to three weeks before 'Honeycrisp'.[10] They are sold to the public in the eastern United States and Canada from retailers starting in September and bring a price about 50% more than the average apple.[11] The apples are available for picking directly off the tree in certain areas. They can be purchased online from mid-September to mid-November, subject to shipping restrictions.[12][13]

The apple variety 'Minneiska' was intentionally bred and selected for its combination of 20 fruit characteristic traits.[14] Certain features are of special importance and this fruit was designed with those in mind. One was the apple's ripening season which was intended to be earlier than most other apples. Another was its texture, which was meant to be unusually crisp, which causes it to be juicer than the normal apple. By default this specifically designed fruit has a longer than normal storage life holding its texture and flavor. The new apple style is often compared to the state fruit of Minnesota, the 'Honeycrisp'.[15]

The 'Minneiska' apple has a texture similar to the 'Minnewashta' and 'Honeycrisp' apples (its parents), with a slightly tart fall spicy citric quality.[16][17] The brand name for the 'Minneiska' is a portmanteau of the words sweet and tang. It is a pinkish apple with a yellow background intermittent with red coloration.[18] The pungent concentrated flavors are more complex than the Honeycrisp; author Amy Traverso compared the apple's flavor to spiced apple cider.[19] The Minnesota recipe writer Teresa Marrone describes it as a zesty sweet-tart flavor that hints at brown sugar.[20]

The 'Minneiska' apple has structure cells that are larger that most other apples.[21] When the apple is bitten, the cells break apart in a distinct fashion that makes a singular cracking sound different than other apples. It has been described by a writer as like the sound made from a board-breaking karate chop.[22]

Exclusive control

The University college of Minnesota awarded exclusive marketing rights to grow, have others raise, and sell the 'Minneiska' apple cultivar and any mutations to Minnesota's largest apple orchard, Pepin Heights Orchards of Lake City, Minnesota.[1][23][24] The orchard in turn in 2006 established a 45-member grower's cooperative named Next Big Thing. These commercial growers were originally only in the state of Minnesota.[23][24] The only planting exception was to Minnesota orchard growers and they were restricted to a fraction of the amount they normally planted of other apple trees.[25][18]

The cooperative later branched out and allowed members from Michigan, Washington, New York and a few other northern states.[26] The apple could not be grown by non-members. Members, who pay royalties for a license on producing the 'Minneiska' trees, can sell the apple only through the cooperative.[23][27] The practice, called “managed variety” for high quality standards,[28] was a new concept to the United States when the apple was developed.[29]

Pepin Heights Orchards owner Dennis Courtier was appointed as the cooperative chairman, and sublicensed the use of the 'Minneiska' variety to the co-op.[30] By January 2007, Next Big Thing had sold memberships worth $380,000, had 30 investors, and was seeking to raise an additional $630,000.[31] The first commercial 'Minneiska' apple trees were planted in the spring.[1] The officials of University of Minnesota registered the word "SweeTango" with the United States Patent Trademark Office as serial number 77262481 on August 23, 2007.[32]

The practice implementation has attracted criticism due to its development through a public research institution.[23][24][27] In 2010, a lawsuit was filed challenging the legality of University of Minnesota selling exclusive rights to the new variety.[18] It was decided in a 2012 ruling by Minnesota's Fourth Judicial District court that the agreement was legal, and that Minnesota's antitrust monopoly laws did not apply to a land-grant university.[33] However, other legal claims were settled between the parties, with the plaintiffs paying $25,000 in legal fees to Pepin Heights Orchards, and an allowance was made for smaller growers to grow up to two thousand 'Minneiska' trees, limited to one hundred thousand per state, as long as the apples are sold only in direct-market channels, and not pooled for wholesale market.[33] The numbers were increased to three thousand trees per orchard, and one hundred and fifty thousand per state, in 2017.[33]

Genetics

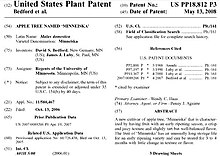

The trademark belongs to University of Minnesota for its apple fruit of the 'Minneiska' cultivar.[34][35] The patent number was obtained on May 13, 2008 by research scientist breeders David S. Bedford and James J. Luby.[10][15][36] The varietal denomination 'Minneiska' has a Latin name of Malus domestica and its patent says in part that it was an exclusive new cultivar that was developed using grafting techniques.[37]

In 2008, the variety was patented by the university, the same year their US patent on the 'Honeycrisp' expired.[38][39] US plant patents are granted for 20 years from the date of application, and exclude others from asexually producing a plant, using the plant, or selling the plant except as authorized by the patent holder.[30][40]

In 2009, a limited number of apples were sold in stores.[13] By 2013, the variety was available at stores across the United States and eastern Canada.[13] The University's fruit-breeding program has produced a new variety of apple in 2014 called the "Frostbite" and is working on future development of additional commercial varieties as replacements.[15] A new apple variety called "First Kiss" in development stages since 2018 shows promise.[41]

References

- Harler, Curt (February 2012). "Lawsuit over apple marketing agreement". Growing Magazine. Moose River Media LLC. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- Woodler 2015, p. 12.

- Leila Navidi (September 16, 2018). "First Kiss was long labor of love". Star Tribune. Minneapolis, Minnesota. p. A15. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Lee Svitak Dean (September 20, 2015). "Minnesota's apple Family Tree". Star Tribune. Minneapolis, Minnesota. p. E5 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Steve Karnowski (September 4, 2009). "Apple growers to release successor to Honeycrisp". Carlsbad Current-Argus. Carlsbad, New Mexico. p. 11. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2020 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - "Which is the apple of your eye". The Baltimore Sun. Baltimore, Maryland. October 14, 2009. p. C2 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Donna Vickroy (October 1, 2009). "The honeycrisp's amazing appeal". Southtown Star. Tinley Park, Illinois. p. 69 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - "Organic SweeTango". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California. September 20, 2015. p. A19. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - "SweeTango(R) apple crop triples in 2011". Reuters (Press release). August 12, 2011. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- "Patents by inventor David S. Bedford". Justia, 2020. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- "Farms, orchards for picking your own apples". The Herald-News. Passaic, New Jersey. September 25, 2013. p. B2 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - USDA 2014, p. 36.

- "SweeTango apples from Next Big Thing hit stores nationwide". PR Web (Press release). September 17, 2013. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- Schneider, Renee Jones (November 12, 2014). "Captain crunch". Star Tribune. Minneapolis, Minnesota. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- Kim Palmer (December 31, 2014). "Looking for the next 'rock star' apple". The Greenville News. Greenville, South Carolina. p. D6. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Susan Taylor (September 14, 2011). "The age of the Apple". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. p. 6-1. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Leila Navidi (September 3, 2009). "Apple growers set to release SweeTango". The Herald. Jasper, Indiana. p. 19. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - "Forbidden Fruit A new apple, the SweeTango, at center of controversy". Leader-Telegram. Eau Claire, Wisconsin. August 30, 2010. p. A5. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Traverso 2011, p. 58.

- Marrone 2016, p. 142.

- Reiss 2014, p. 30.

- Reiss 2014, p. 31.

- Parker, Rosemary (September 13, 2011). "Better than Honeycrisp? SweeTango apples hit Michigan Meijer and Wal-Mart stores this week". MLive. MLive Media Group. Archived from the original on December 14, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2012.

- "Next Big Thing is new co-op for marketing MN1914 apple". Fruit Growers News. Great American Media Services. 2020. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- Chris Hubbuch (August 29, 2010). "Forbidden Fruit". The La Crosse Tribune. La Crosse, Wisconsin. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Woodler 2015, p. 19.

- Seabrook, John (November 21, 2011). "Crunch: Building a better apple". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on October 3, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- "Minnesota Hardy / Sweetango". University of Minnesota / Minnesota Agricultural Experimental Station, 2020. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- Steve Karnowski (September 8, 2009). "The Next Big Thing / Apple growers sweet on new variety". The Advocate-Messenger. Danville, Kentucky. p. 4. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Karst, Tom (September 20, 2011). "SweeTango deal intact after settlement". The Packer. Vance Publishing Corporation. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- Grayson, Katharine (January 7, 2007). "Co–op seeks $600K to seed apple". Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal. American City Business Journals. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- "SweeTango – reviews & brand information". LegalForce Trademarkia. Trademarkia, Inc. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- "Litigants settle SweeTango dispute". Fruit Growers News. Great American Media Services. November 2011. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- "Minnesota Arboretum". Arboretum.umn.edu. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved January 18, 2012.

- "Minnesota Hardy, p. 26" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 22, 2012. Retrieved January 18, 2012.

- "Crunch / Building a better apple by John Seabrook". Conde Nest, 2020. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- United States 2008, p. 10.

- Brown, SK; Maloney, KE (2009). "Making sense of new apple varieties, trademarks and clubs: current status" (PDF). New York Fruit Quarterly. 17 (3). New York. pp. 9–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- Olson, Dan (October 21, 2007). "Honeycrisp apple losing its patent protection, but not its appeal". MPR News. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Public Radio. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- Bouchoux, Deborah (April 21, 2008). Patent Law for Paralegals. Cengage Learning. p. 77. ISBN 1-4180-4801-1. Archived from the original on June 26, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- Fish, Noah (September 24, 2018). "The Best of Both Worlds / Minnesota orchards debut First Kiss apple variety". The Winona Daily News. Winona, Minnesota. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

Sources

- Marrone, Teresa (2016). Dishing up Minnesota. Storey Publishing. ISBN 9781612125855.

- Reiss, Marcia (2014). Apple. Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780233826.

- Traverso, Amy (2011). The Apple Lover's Cookbook. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780393241846.

- United States, Patent Office (2008). United States Plant Patents. United States Patent & Trademark Office. OCLC 27833628.

- USDA (2014). Rural Cooperatives. United States Department of Agriculture. OCLC 818916630.

- Woodler, Olwen (2015). The Apple Cookbook / 125 Freshly Picked Recipes. Storey Publishings. ISBN 9781612125190.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to SweeTango. |

- HuffPost Taste

- "The Miracle Apple" podcast at Planet Money (14 mins, 2016)