Jealousy in art

Jealousy in art deals with the way in which writers, musicians and graphic artists have approached the topic of jealousy in their works.

Literature

Literary works use a variety of devices to explore its possibilities and reveal its wider implications. Most famously, perhaps, Schahriar's destructive jealousy in One Thousand and One Nights is what precipitates Scheherazade's creative outpouring of stories. In Ariosto’s Orlando furioso (1516) jealousy leads to such a distortion of the world that the sufferer is driven to madness. Shakespeare's later play, the Winters tale (1613) is predominately about the jealousy felt by Leontes' and his supposed adulterous wife.

E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Princess Brambilla (1821) is more concerned with the interplay between jealousy and the theater, between reality and masks. In Charlotte Brontë’s Villette (1853) jealousy becomes a game of reflections and speculations, a potent denial of sexual stereotypes, and, like many novels written by women, an angry rejection of the violation of the individual caused by the gaze of the jealous lover. Anthony Trollope uses both He Knew He Was Right (1869) and Kept in the Dark (1882) to analyze not only double standards used to judge how men and women behave but also the relationship between mind and body. Tolstoy’s The Kreutzer Sonata (1889) offers a compelling exploration of jealousy acting as a front for repressed homosexuality. Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (1913–1927), especially the section concerning Albertine, represents the claustrophobic nature of the passion of jealousy through the tropes of imprisonment, illness and death, while Michal Choromanski’s Jealousy and Medicine (1932) creates a landscape and a climate that recreate to the full the physical experience of jealousy. Freud’s reading of jealousy and his emphasis on repetitive structures inspires Iris Murdoch’s A Word Child (1975) in which the London subway symbolizes endless repetition of the same.

Other novelists have used jealousy to explore the relationship between writer and reader, as well as that between fiction and reality. Alain Robbe-Grillet’s Jealousy (1965) develops the image of the window blind (in French “la jalousie” means both the emotion and the window blind) to lock the reader into the jealous person's mind, while in Julian Barnes’s Talking it Over (1991), the writer’s jealousy of the reader’s attention is as much a part of the story as the sexual jealousy it also examines. A. S. Byatt’s Possession (1990) is in part an analysis of the ways in which writing and reading operate to silence other voices.

The topic also comes up in Isaac Disraeli's writing as a literary tool.[1]

Visual arts

In art, depicting a face reflecting the ravages of jealousy was a frequent studio exercise: see for instance drawings by Charles Le Brun (1619–1690) or Sébastien Leclerc the Younger, or in a fuller treatment, the howling figure on the left in Bronzino’s An Allegory with Venus and Cupid (probably 1540-50). Albrecht Dürer’s 1498 drawing, Hercules’s Jealousy depicts jealousy as a powerfully built woman armed with a sword.[2] The theme of jealousy is frequently conveyed through images of the gaze as in Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Paolo and Francesca (1819) which reveals the jealous husband’s gaze catching the young lovers’ first kiss.[3]

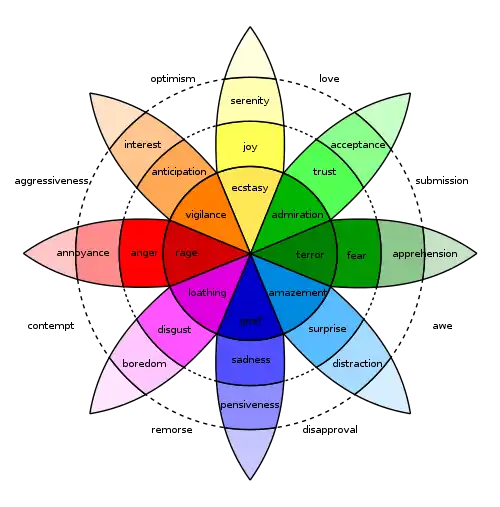

Edvard Munch’s many depictions of jealousy, however, tend to place the husband at the front of the painting with a couple behind him as if to suggest that jealousy is created more by the mind than by the gaze. This suggestion is intensified by his use of symbolic colors.[4] There are, nevertheless, lighter moments, as when Gaston La Touche (1854–1913), in Jealousy or the Monkey shows a love scene interrupted by a monkey tugging on the woman's dress.[5] While popular images of jealousy tend to the lurid, it remains a source, both in literature and in painting, of highly creative artistic strategies that have little to do with the negative and destructive sides of the emotion itself.

On a larger scale, this was also prevalent as Italian cities competed with one another for prestige as an art destination.[6]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jealousy in art. |

References

- Disraeli, Isaac (1881). Literary character, or, History of men of genius. Armstrong. pp. 207–213.

- Print Quarterly, Volume 4, Issues 1-4, 1987

- Jover 2005, p. 106.

- "Sjalusi". munch.emuseum.com. Retrieved 2021-02-03.

- "Musée d'Orsay: Notice d'Oeuvre". www.musee-orsay.fr. Retrieved 2021-02-03.

- The Art Journal: New series. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: D. Appleton & Company. 1876. p. 154.