Emotions and culture

According to some theories, emotions are universal phenomena, albeit affected by culture. Emotions are "internal phenomena that can, but do not always, make themselves observable through expression and behavior".[1] While some emotions are universal and are experienced in similar ways as a reaction to similar events across all cultures, other emotions show considerable cultural differences in their antecedent events, the way they are experienced, the reactions they provoke and the way they are perceived by the surrounding society. According to other theories, termed social constructionist, emotions are more deeply culturally influenced. The components of emotions are universal, but the patterns are social constructions. Some also theorize that culture is affected by emotions of the people.

Cultural studies of emotions

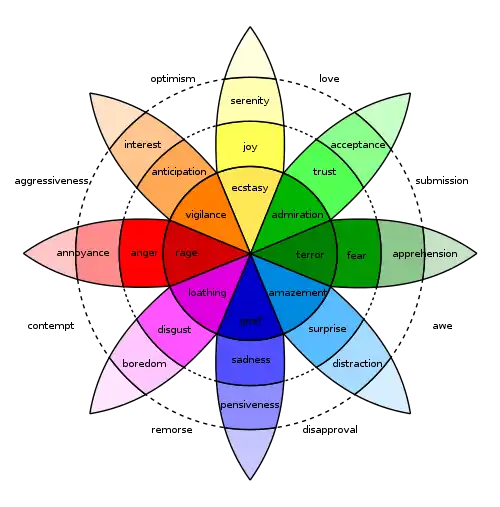

Research on the relationship between culture and emotions dates back to 1872 when Darwin[2] argued that emotions and the expression of emotions are universal. Since that time, the universality of the seven basic emotions[3] (i.e., happiness, sadness, anger, contempt, fear, disgust, and surprise) has ignited a discussion amongst psychologists, anthropologists, and sociologists. While emotions themselves are universal phenomena, they are always influenced by culture. How emotions are experienced, expressed, perceived, and regulated varies as a function of culturally normative behavior by the surrounding society. Therefore, it can be said that culture is a necessary framework for researchers to understand variations in emotions.[4]

Pioneers

In Darwin's opening chapter of The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, (1872/1998) Darwin considered the face to be the preeminent medium of emotional expression in humans, and capable of representing both major emotions and subtle variations within each one. Darwin's ideas about facial expressions and his reports of cultural differences became the foundation for ethological research strategies. Silvan Tomkins' (1962) Affect Theory[5] 1963[6]) built upon Darwin's research, arguing that facial expressions are biologically based, and universal manifestations of emotions. The research of Paul Ekman (1971)[7] and Carroll Izard (1971)[8] further explored the proposed universality of emotions, showing that the expression of emotions were recognized as communicating the same feelings in cultures found in Europe, North and South America, Asia, and Africa. Ekman (1971)[7] and Izard (1971)[8] both created sets of photographs displaying emotional expressions that were agreed upon by Americans. These photographs were then shown to people in other countries with the instructions to identify the emotion that best describes the face. The work of Ekman, and Izard, concluded that facial expressions were in fact universal, innate, and phylogenetically derived. Some theorists, including Darwin, even argued that "Emotion ... is neuromuscular activity of the face". Many researchers since have criticized this belief and instead argue that emotions are much more complex than initially thought. In addition to pioneering research in psychology, ethnographic accounts of cultural differences in emotion began to emerge. Margaret Mead, a cultural anthropologist writes about unique emotional phenomena she experienced while living among a small village of 600 Samoans on the island of Ta'u in her book Coming of Age in Samoa.[9] Gregory Bateson, an English anthropologist, social scientist, linguist, and visual anthropologist used photography and film to document his time with the people of Bajoeng Gede in Bali. According to his work, cultural differences were very evident in how the Balinese mothers displayed muted emotional responses to their children when the child showed a climax of emotion. In displays of both love (affection) and anger (temper) Bateson's notes documented that mother and child interactions did not follow Western social norms. The fieldwork of anthropologist Jean Briggs[10] details her almost two year experience living with the Utku Inuit people in her book Never in Anger: Portrait of an Eskimo Family. Briggs lived as the daughter of an Utku family describing their society as particularly unique emotional control. She rarely observed expressions of anger or aggression and if it were expressed, it resulted in ostracism.

Scholars working on the history of emotions have provided some useful terms for discussing cultural emotion expression. Concerned with distinguishing a society's emotional values and emotional expressions from an individual's actual emotional experience, William Reddy has coined the term emotive. In The Making of Romantic Love, Reddy uses cultural counterpoints to give credence to his argument that romantic love is a 12th-century European construct, built in a response to the parochial view that sexual desire was immoral. Reddy suggests that the opposition of sexual ardor and true love was not present in either Heain Japan or the Indian kingdoms of Bengal and Orissa.[11] Indeed, these cultures did not share the view of sexual desire as a form of appetite, which Reddy suggests was widely disseminated by the Church. Sexuality and spirituality were not conceived in a way which separated lust from love: indeed, sex was often used as a medium of spiritual worship, emulating the divine love between Krishna and Rada.[11] Sexual desire and love were inextricable from one another. Reddy therefore argues that the emotion of romantic love was created in Europe in the 12th century, and was not present in other cultures at the time.[11]

Cultural norms of emotions

Culture provides structure, guidelines, expectations, and rules to help people understand and interpret behaviors. Several ethnographic studies suggest there are cultural differences in social consequences, particularly when it comes to evaluating emotions. For example, as Jean Briggs described in the Utku Eskimo population, anger was rarely expressed, and in the rare occasion that it did occur, it resulted in social ostracism. These cultural expectations of emotions are sometimes referred to as display rules. Psychologists (Ekman & Friesen, 1969;[12] Izard, 1980;[13] Sarni, 1999[14]) believe that these rules are learned during a socialization process. Ekman and Friesen (1975)[15] have also suggested that these "unwritten codes" govern the manner in which emotions may be expressed, and that different rules may be internalized as a function of an individual's culture, gender or family background. Miyamoto & Ryff (2011)[16] used the term cultural scripts to refer to cultural norms that influence how people expect emotions to be regulated. Cultural scripts dictate how positive and negative emotions should be experienced and combined. Cultural scripts may also guide how people choose to regulate their emotions which ultimately influences an individual's emotional experience. For example, research suggests that in Western cultures, the dominant social script is to maximize positive emotions and minimize negative emotions.[17] In Eastern cultures, the dominant cultural script is grounded in "dialectical thinking" and seeking to find a middle way by experiencing a balance between positive and negative emotions. Because normative behaviors in these two cultures vary, it should also be expected that their cultural scripts would also vary. Tsai et al. (2007)[18] argues that not only do cultural factors influence ideal affect (i.e., the affective states that people ideally want to feel) but that the influence can be detected very early. Their research suggests that preschool aged children are socialized to learn ideal affect through cultural products such as children storybooks. They found that European American preschool children preferred excited (vs. calm) smiles and activities more and perceived an excited (vs. calm) smile as happier than Taiwanese Chinese preschoolers. This is consistent with American best sellers containing more excited and arousing content in their books than the Taiwanese best sellers. These findings suggest that cultural differences in which emotions are desirable or, ideal affect, become evident very early.

Culture and emotional experiences

A cultural syndrome as defined by Triandis (1997)[19] is a "shared set of beliefs, attitudes, norms, values, and behavior organized around a central theme and found among speakers of one language, in one times period, and in one geographic region". Because cultures are shared experiences, there are obvious social implications for emotional expression and emotional experiences. For example, the social consequences of expressing or suppressing emotions will vary depending upon the situation and the individual. Hochschild (1983)[20] discussed the role of feeling rules, which are social norms that prescribe how people should feel at certain times (e.g. wedding day, at a funeral). These rules can be general (how people should express emotions in general) and also situational (events like birthdays). Culture also influences the ways emotions are experienced depending upon which emotions are valued in that specific culture. For example, happiness is generally considered a desirable emotion across cultures. In countries with more individualistic views such as America, happiness is viewed as infinite, attainable, and internally experienced. In collectivistic cultures such as Japan, emotions such as happiness are very relational, include a myriad of social and external factors, and reside in shared experiences with other people. Uchida, Townsend, Markus, & Bergseiker (2009)[21] suggest that Japanese contexts reflect a conjoint model meaning that emotions derive from multiple sources and involve assessing the relationship between others and the self. However, in American contexts, a disjoint model is demonstrated through emotions being experienced individually and through self-reflection. Their research suggests that when Americans are asked about emotions, they are more likely to have self-focused responses "I feel joy" whereas a Japanese typical reaction would reflect emotions between the self and others "I would like to share my happiness with others."

Culture and emotion regulation

Emotions play a critical role in interpersonal relationships and how people relate to each other. Emotional exchanges can have serious social consequences that can result in either maintaining and enhancing positive relationships, or becoming a source of antagonism and discord (Fredrickson, 1998;[22] Gottman & Levenson, 1992)[23]). Even though people may generally "want to feel better than worse" (Larsen, 2000),[24]) how these emotions are regulated may differ across cultures. Research by Yuri Miyamoto suggests that cultural differences influence emotion regulation strategies. Research also indicates that different cultures socialize their children to regulate their emotions according to their own cultural norms. For example, ethnographic accounts suggest that American mothers think that it is important to focus on their children's successes while Chinese mothers think it is more important to provide discipline for their children.[25] To further support this theory, a laboratory experiment found that when children succeeded on a test, American mothers were more likely than Chinese mothers to provide positive feedback (e.g. "You're so smart!"), in comparison to Chinese mothers who provided more neutral or task relevant feedback (e.g. "Did you understand the questions or did you just guess?"; Ng, Pomerantz, & Lam, 2007[26]). This shows how American mothers are more likely to "up-regulate" positive emotions by focusing on their children's success whereas Chinese mothers are more likely to "down-regulate" children's positive emotions by not focusing on their success. Americans see emotions as internal personal reactions; emotions are about the self (Markus & Kityama, 1991[27]). In America, emotional expression is encouraged by parents and peers while suppression is often disapproved. Keeping emotions inside is viewed as being insincere as well as posing a risk to one's health and well being.[28] In Japanese cultures, however, emotions reflect relationships in addition to internal states. Some research even suggests that emotions that reflect the inner self cannot be separated from emotions that reflect the larger group. Therefore, unlike American culture, expression of emotions is often discouraged, and suppressing one's individual emotions to better fit in with the emotions of the group is looked at as mature and appropriate.[29]

Emotional perception and recognition

The role of facial expressions in emotional communication is often debated. While Darwin believed the face was the most preeminent medium of emotion expression, more recent scientific work challenges that theory. Furthermore, research also suggests that cultural contexts behave as cues when people are trying to interpret facial expressions. In everyday life, information from people's environments influences their understanding of what a facial expression means. According to research by Masuda et al. (2008),[30] people can only attend to a small sample of the possible events in their complex and ever- changing environments, and increasing evidence suggests that people from different cultural backgrounds allocate their attention very differently. This means that different cultures may interpret the same social context in very different ways. Since Americans are viewed as individualistic, they should have no trouble inferring people's inner feelings from their facial expressions, whereas Japanese people may be more likely to look for contextual cues in order to better understand one's emotional state. Evidence of this phenomenon is found in comparisons of Eastern and Western artwork. In Western art there is a preoccupation with the face that does not exist in Eastern art. For example, in Western art the figure occupies a larger part of the frame and is clearly noticeably separated from the ground. In East Asian artwork, the central figure is significantly smaller and also appears to be more embedded in the background.[31] In a laboratory setting, Masuda et al.[30] also tested how sensitive both Americans and Japanese would be to social contexts by showing them pictures of cartoons that included an individual in the context of a group of four other people. They also varied the facial expressions of the central figure and group members. They found that American participants were more narrowly focused with judging the cartoon's emotional states than the Japanese participants were. In their recognition task they also observed that the Japanese participants paid more attention to the emotions of the background figures than Americans did.

Individualistic vs. collectivistic cultures

Contemporary literature has traced the influence of culture on a variety of aspects of emotion, from emotional values to emotion regulation. Indeed, culture may be best understood as a channel through which emotions are molded and subsequently expressed. Indeed, this had been most extensively discussed in psychology by examining individualistic and collectivistic cultures.

The individualistic vs. collectivistic cultural paradigm has been widely used in the study of emotion psychology. Collectivistic cultures are said to promote the interdependence of individuals and the notion of social harmony. Indeed, Niedenthal suggests that: "The needs, wishes, and desires of the collectives in which individuals find themselves are emphasized, and the notion of individuality is minimized or even absent from the cultural model".[1] Individualistic cultures, however, promote individual autonomy and independence. Individual needs, wishes, and desires are emphasized and the possibility of personal attainment is encouraged. Collectivistic cultures include those of Asia and Latin America, whilst individualistic cultures include those of North America and Western Europe. North America, specifically, is seen to be the prototype of an individualistic culture.[1]

Research has shown that the collectivism vs. individualism paradigm informs cultural emotional expression. An influential paper by Markus & Kitayama, on the influence of culture on emotion, established that in more collectivistic cultures, emotions were conceived as relational to the group.[32] Thus, in collectivistic cultures, emotions are believed to occur between people, rather than within an individual.[32] When Japanese school students were asked about their emotions, they usually stated than an emotion comes from their outside social surroundings.[33] When asked about where the emotions they feel originate from, Japanese school students never referred to themselves first.[33] This suggests that Japanese people believe emotions exist within the environment, between individuals, in line with collectivistic values.[33] Individualistic cultures, however, conceive emotions as independent internal experiences, occurring within an individual. When American school students were asked about their emotions, they usually stated that they experienced emotions within themselves.[33] This suggests that Americans consider emotions as personal, experienced internally and independently. Markus & Kitayama purport that emotions like friendliness and shame - which promote interconnectedness - are predominant in Asian culture. Conversely, European-American cultures were shown to be predominated by individualistic emotions, such as pride or anger.[32]

Emotion suppression

Collectivistic cultures are believed to be less likely to express emotions, in fear of upsetting social harmony. Miyahara, referencing a study conducted on Japanese interpersonal communication, purports that the Japanese "are low in self disclosure, both verbally and non-verbally....Most of these attributes are ascribed to the Japanese people's collectivistic orientations".[34] The study conducted showed that Japanese individuals have a relatively low expression of emotion. Niedenthal further suggests that: "Emotional moderation in general might be expected to be observed in collectivist cultures more than in individualistic cultures, since strong emotions and emotional expression could disrupt intra-group relations and smooth social functioning".[1]

Individualistic cultures are seen to express emotions more freely than collectivistic cultures. In a study comparing relationships among American and Japanese individuals, it was found that: "People in individualistic cultures are motivated to achieve closer relationships with a selected few, and are willing to clearly express negative emotions towards others".[35] Research by Butler et al., found that the social impact of emotion suppression is moderated by the specific culture. Whilst the suppression of emotion by those with European Americans values led to non-responsive reactions and hostility, individuals with bicultural Asian-American values were perceived as less hostile and more engaged when they suppressed their emotions.[36] Thus, individuals with Asian-American values were more skilled in emotional suppression than individuals with European-American values. The article explanation is that Asian-Americans may engage in habitual suppression more often as negative emotions are seen to cause social disharmony and thus contradict cultural values.[36]

Culture and emotion socialization

Research undertaken in the socialization of children cross-culturally has shown how early cultural influences start to affect emotions. Studies have shown the importance of socializing children in order to imbue them with emotional competence.[37] Research by Friedlmeier et al., suggests children must be socialized in order to meet the emotional values and standards of their culture.[37] For instance, in dealing with negative emotions, American parents were more likely to encourage emotion expression in children, thus promoting autonomy and individualistic competence.[37] East Asian parents, however, attempted to minimize the experience of the negative emotion, by either distracting their child or trying to make their child suppress the emotion. This promotes relational competence and upholds the value of group harmony.[37] Children are thus socialized to regulate emotions in line with cultural values.

Further research has assessed the use of storybooks as a tool with which children can be socialized to the emotional values of their culture.[38] Taiwanese values promote ideal affect as a calm happiness, where American ideal affect is excited happiness.[38] Indeed, it was found that American preschoolers preferred excited smiles and perceived them as happier than Taiwanese children did, and these values were seen to be mirrored in storybook pictures.[38] Importantly, it was shown that across cultures, exposure to story books altered children's preferences. Thus, a child exposed to an exciting (versus calm) book, would alter their preference for excited (versus calm) activity.[38] This shows that children are largely malleable in their emotions, and suggests that it takes a period of time for cultural values to become ingrained.

Another study has shown that American culture values high arousal positive states such as excitement, over low arousal positive states such as calmness.[39] However, in Chinese culture low arousal positive states are preferable to high arousal positive states. The researchers provide a framework to explain this, suggesting that high arousal positive states are needed in order to influence someone else, where low arousal positive states are useful for adjusting to someone else.[39] This explanation is in line with the collectivism-individualism dichotomy: American values promote individual autonomy and personal achievement, where Asian values promote relational harmony. Emotion expression is consequently seen to be influenced largely by the culture in which a person has been socialized.

Culture of honor

Nisbett & Cohen's 1996 study Culture of Honor examines the violent honor culture in the Southern states of the USA. The study attempts to address why the southern USA is more violent, with a higher homicide rate, than its northern counterpart. It is suggested that the higher rate of violence is due to the presence of a 'culture of honor' in the southern USA.[40] A series of experiments were designed to determine whether southerners got angrier than northerners when they were insulted. In one example, a participant was bumped into and insulted, and their subsequent facial expressions were coded. Southerners showed significantly more anger expressions.[40] Furthermore, researchers measured cortisol levels, which increase with stress and arousal, and testosterone levels, which increase when primed for aggression. In insulted southerners, cortisol and testosterone levels rose by 79% and 12% respectively, which was far more than in insulted northerners.[40] With their research, Nisbett & Cohen show that southern anger is expressed in a culturally specific manner.

Challenges in cultural research of emotions

One of the biggest challenges in cultural research and human emotions is the lack of diversity in samples. Currently, the research literature is dominated by comparisons between Western (usually American) and Eastern Asian (usually Japanese or Chinese) sample groups. This limits our understanding of how emotions vary and future studies should include more countries in their analyses. Another challenge outlined by Matsumoto (1990)[41] is that culture is ever changing and dynamic. Culture is not static. As the cultures continue to evolve it is necessary that research capture these changes. Identifying a culture as "collectivistic" or "individualistic" can provide a stable as well as inaccurate picture of what is really taking place. No one culture is purely collectivistic or individualistic and labeling a culture with these terms does not help account for the cultural differences that exist in emotions. As Matsumoto argues, a more contemporary view of cultural relations reveals that culture is more complex than previously thought. Translation is also a key issue whenever cultures that speak different languages are included in a study. Finding words to describe emotions that have comparable definitions in other languages can be very challenging. For example, happiness, which is considered one of the six basic emotions, in English has a very positive and exuberant meaning. In Hindi, Sukhi is a similar term however it refers to peace and happiness. Although happiness is a part of both definitions, the interpretation of both terms could lead to researchers to making assumptions about happiness that actually do not exist.

Further research

Studies have shown that Western and Eastern cultures have distinct differences in emotional expressions with respect to hemi-facial asymmetry; Eastern population showed bias to the right hemi-facial for positive emotions, while the Western group showed left hemi-facial bias to both negative and positive emotions.[42]

Recently, the valence and arousal of the twelve most popular emotion keywords expressed on the micro-blogging site Twitter were measured using latent semantic clustering in three geographical regions: Europe, Asia and North America. It was demonstrated that the valence and arousal levels of the same emotion keywords differ significantly with respect to these geographical regions — Europeans are, or at least present themselves as more positive and aroused, North Americans are more negative and Asians appear to be more positive but less aroused when compared to global valence and arousal levels of the same emotion keywords.[43] This shows that emotional differences between Western and Eastern cultures can, to some extent, be inferred through their language style.

Conclusion

Culture affects every aspect of emotions. Identifying which emotions are good or bad, when emotions are appropriate to be expressed, and even how they should be displayed are all influenced by culture. Even more importantly, cultures differently affect emotions, meaning that exploring cultural contexts is key to understanding emotions. Through incorporating sociological, anthropological, and psychological research accounts it can be concluded that exploring emotions in different cultures is very complex and the current literature is equally as complex, reflecting multiple views and the hypothesis.

See also

References

- Niedenthal, Paula M.; Silvia Krauth-Gruber; Francois Ric (2006). Psychology of Emotion Interpersonal, Experiential, and Cognitive Approaches. New York, NY: Psychology Press. pp. 5, 305–342. ISBN 978-1841694023.

- Darwin, C (1998). The expression of emotions in man and animals. London.

- Ekman, P (1992). "Are there basic emotions?". Psychological Review. 99 (3): 550–553. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.99.3.550. PMID 1344638. S2CID 34722267.

- Richeson, P. J. & Boyd, R. (2005). Not by genes alone: How culture transformed human evolution. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Tomkins, S.S. (1962). Affect, imagery, consciousness: Vol 1. The positive effects. New York: Springer.

- Tomkins, S. S. (1962). Affect, imagery, consciousness: Vol 2. The positive affects. New York: Springer.

- Ekman, P. (1971). Universal and cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Izard, C. E. (1971). The face of emotions. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Mead, M. (1961). Coming of age in Samoa: A psychological study of primitive you for western civilization. New York: Morrow.

- Briggs, J. L. (1970). Never in anger: Portrait of an Eskimo family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Reddy, W. (2012). The Making of Romantic Love: Longing and Sexuality in Europe, South Asia, and Japan, 900–1200 CE. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226706276.

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W. V. (1969). "The repertoire of nonverbal behavior: Categories, origins, usage, and coding". Semiotica. 1: 49–98. doi:10.1515/semi.1969.1.1.49.

- Izard, C. E. (1980). Cross-cultural perspectives on emotion and emotion communication. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. pp. 23–50.

- Sarni, C. (1990). The development of emotional competence. New York: Guilford.

- Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V. (1975). Unmasking the face. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Miyamoto, Y.; Ryff, C (2011). "Cultural differences in the dialectical and non-dialectical emotional styles and their implications for health". Cognition and Emotion. 25 (1): 22–30. doi:10.1080/02699931003612114. PMC 3269302. PMID 21432654.

- Kityama, S.; Markus, H.; Kityama, S. (1999). "Is there a universal need for positive self-regard?". Psychological Review. 106 (4): 766–794. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.321.2156. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.766. PMID 10560328.

- Tsai, J. L.; Louie, J. Y.; Chen, E. E.; Uchida, Y. (2007). "Learning what feelings to desire: Socialization of ideal affect through children's storybooks". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 33 (1): 17–30. doi:10.1177/0146167206292749. PMID 17178927.

- Triandis, H. (1997). Cross-cultural perspectives on personality. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 439–464.

- Hochschild, R. (1983). The managed heart. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Uchida, Y.; Townsend, S.S.M.; Markus, H.R.; Bergseiker, H.B (2009). "Emotios as within or between people? Cultural variations in lay theories of emotion expression and inference". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 35 (11): 1427–1438. doi:10.1177/0146167209347322. PMID 19745200.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). "What good are positive emotions?". Review of General Psychology. 2 (3): 300–319. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300. PMC 3156001. PMID 21850154.

- Gottman, J. M.; Levensen, R. W. (1992). "Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology, and health". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 63 (2): 221–233. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.63.2.221. PMID 1403613.

- Larsen, R. (2000). "Toward a science of mood regulation". Psychological Inquiry. 11 (3): 129–141. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1103_01.

- Miller, P.; Wang, S.; Sandel, T.; Cho, G. (2002). "Self-esteem as folk theory: A comparison of European American and Taiwanese mothers' beliefs". Parenting: Science and Practice. 2 (3): 209–239. doi:10.1207/S15327922PAR0203_02.

- Ng, F.; Pomerantz, E.; Lam, S. (2007). "European American and Chinese parents' responses to children's success and failure: Implications for children's responses". Developmental Psychology. 43 (5): 1239–1255. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1239. PMID 17723048.

- Markus, H. R.; Kityama, S. (2007). "Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation". Psychological Review. 98 (2): 224–253. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.320.1159. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224.

- Richards, J. M.; Gross, J. J. (2000). "Emotion regulation and memory: The cognitive costs of keeping one's cool". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 79 (3): 410–424. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.688.5302. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.3.410. PMID 10981843.

- Rothbaum, F.; Pott, M.; Azuma, H.; Miyake, K.; Weisz, J. (2000). "The development of close relationships in Japan and the US: Pathways of symbiotic harmony and generative tension". Child Development. 71 (5): 1121–1142. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00214. PMID 11108082.

- Masuda, T.; Ellsworth, P. C.; Mequita, B.; Leu, J.; Tanida, S.; Van de Veerdonk, E. (2008). "Placing the face in context: Cultural differences in the perception of facial emotion". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 94 (3): 365–381. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.365. PMID 18284287.

- Nisbett, R. E.; Masuda, T. (2003). "Culture and point of view". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (19): 11163–70. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10011163N. doi:10.1073/pnas.1934527100. PMC 196945. PMID 12960375.

- Markus, H. & Kitayama, S. (1991). "Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation". Psychological Review. 98 (2): 224–253. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.320.1159. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.98.2.224.

- Uchida, Y.; Townsend, S. S. M.; Markus, H. R. & Bergsieker, H. B. (2009). "Emotions as within or between people? Cultural variation in lay theories of emotion expression and inference". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 35 (11): 1427–1439. doi:10.1177/0146167209347322. PMID 19745200.

- Miyahara, Akira. "Toward Theorizing Japanese Communication Competence from a Non-Western Perspective". American Communication Journal. 3 (3).

- Takahashi, Keiko Naomi Ohara; Toni C. Antonucci; Hiroko Akiyama (September 1, 2002). "Commonalities and differences in close relationships among the Americans and Japanese: A comparison by the individualism/collectivism concept". International Journal of Behavioral Development. 26 (5): 453–465. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1029.6705. doi:10.1080/01650250143000418.

- Butler, E. A.; Lee, T. L. & Gross, J. J. (2007). "Emotion regulation and culture: Are the social consequences of emotion suppression culture-specific?". Emotion. 7 (1): 30–48. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.688.4212. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.30. PMID 17352561.

- Friedlmeier, W.; Corapci, F. & Cole, P. M. (2011). "Socialization of emotions in cross-cultural perspective". Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 5 (7): 410–427. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00362.x.

- Tsai J.L.; Louie J.Y.; Chen E.E.; Uchida Y. (2007). "Learning what feelings to desire: Socialization of ideal affect through children's storybooks". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 33 (1): 17–30. doi:10.1177/0146167206292749. PMID 17178927.

- Tsai J.L.; Miao F.F.; Seppala E.; Fung H.H.; Yeung D.Y. (2007). "Influence and adjustment goals: Sources of cultural differences in ideal affect". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 92 (6): 1102–1117. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1102. PMID 17547491. S2CID 19510260.

- Nisbett, R.E. & Cohen, D. (1996). Culture of honor: The psychology of violence in the South. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0813319933.

- Matsumoto, D. (1990). "Cultural similarities and differences in display rules". Motivation and Emotion. 14 (3): 195–214. doi:10.1007/BF00995569.

- Mandal M. K.; Harizuka S.; Bhushan B. & Mishra R.C. (2001). "Cultural variation in hemi-facial asymmetry of emotion expressions". British Journal of Social Psychology. 40 (3): 385–398. doi:10.1348/014466601164885. PMID 11593940.

- Bann, E. Y.; Bryson, J. J. (2013), "Measuring Cultural Relativity of Emotional Valence and Arousal using Semantic Clustering and Twitter", Proceedings of the 35th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, pp. 1809–1814, arXiv:1304.7507, Bibcode:2013arXiv1304.7507Y