Tecumseh

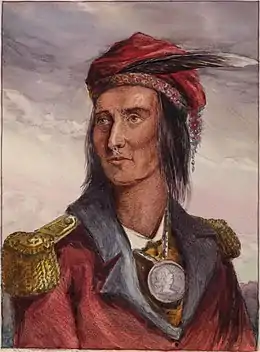

Tecumseh (/tɪˈkʌmsə, tɪˈkʌmsi/ ti-KUM-sə, ti-KUM-see (c. 1768 – October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief, warrior, diplomat, and orator who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. He traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and promoting tribal unity. Although his efforts to unite Native Americans ended with his death in the War of 1812, he became an iconic folk hero in American, Indigenous, and Canadian history.

Tecumseh | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1768 Likely present-day Chillicothe, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | October 5, 1813 (aged about 45) |

| Cause of death | killed in the Battle of the Thames |

| Burial place | unknown |

| Nationality | Shawnee |

| Known for | organizing Native American resistance to U.S. expansion |

| Relatives |

|

Tecumseh was born in what is now Ohio at time when the far-flung Shawnees were reuniting in their Ohio Country homeland. During his childhood, the Shawnees lost territory to the expanding American colonies in a series of border conflicts. Tecumseh's father was killed in battle against American colonists in 1774. Tecumseh was thereafter mentored by his older brother Cheeseekau, a noted war chief who died fighting Americans in 1792. As a young war leader, Tecumseh joined Shawnee Chief Blue Jacket's war to defend against further American encroachment, which ended in defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 and the loss of most of Ohio in the 1795 Treaty of Greenville.

In 1805, Tecumseh's younger brother Tenskwatawa, who came to be known as the Shawnee Prophet, founded a religious movement, calling upon Native Americans to reject European influences and return to a more traditional lifestyle. In 1808, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa established Prophetstown, a village near present-day Lafayette, Indiana, that grew into a large, multi-tribal community. Tecumseh traveled constantly, spreading the Prophet's message and eclipsing his brother in prominence. He proclaimed that Native Americans owned their lands in common, and urged tribes not cede more territory unless all tribes agreed. His message alarmed American leaders as well as Native leaders who sought accommodation with the U.S. In 1811, when Tecumseh was in the south recruiting allies, Americans under William Henry Harrison defeated Tenskwatawa at the Battle of Tippecanoe and destroyed Prophetstown.

After the outbreak of the War of 1812, Tecumseh joined his cause with the British, recruiting warriors and helping to capture Detroit in August 1812. He led a large contingent of warriors in an 1813 campaign in Ohio against Fort Meigs. When U.S. naval forces took control of Lake Erie in 1813, Tecumseh reluctantly retreated with the British into Upper Canada, where American forces engaged them at the Battle of the Thames on October 5, 1813, in which Tecumseh was killed. His death caused the pan-Indian alliance to collapse; the lands he fought to defend were eventually ceded to the U.S. government. His legacy as one of the most celebrated Native American leaders in history grew in the years after his death.

Early life

Tecumseh was not mentioned in contemporary historical documents for about the first forty years of his life, so historians have reconstructed his early life based on later testimony. He was born in Shawnee territory in what is now Ohio between 1764 and 1771; the best evidence suggests a birthdate of around March 1768.[1] Shawnees pronounced his name as "Tecumtha."[2] He was born into the panther clan of the Kispoko division of the Shawnee tribe. Like most Shawnees, his name indicated his clan: translations of his name from the Shawnee language include "I Cross the Way," and "Shooting Star," references to a meteor associated with the panther clan.[1] Later stories claimed that Tecumseh was named after a shooting star that appeared at his birth, although his father and most of his siblings, as members of the panther clan, were named after the same meteor.[3]

Tecumseh was probably born in the Shawnee town of Chillicothe, along the Scioto River, near present-day Chillicothe, Ohio, or in a nearby Kispoko village.[1] A few years after Tecumseh's birth, Shawnees moved to the northwest, establishing a new Chillicothe (present Oldtown, Ohio). In the early 20th century, people mistakenly identified this newer Chillicothe as Tecumseh's birthplace, unaware the town did not exist when Tecumseh was born.[1] As a result, the official Ohio historical marker designating Tecumseh's birthplace is 50 miles (80 km) from the actual location.[4]

Tecumseh's father, Puckeshinwau, was a Shawnee war chief of the Kispoko division.[5] Tecumseh's mother, Methoataaskee, probably belonged to the Pekowi division and the turtle clan, although some traditions maintain that she was Creek.[5] Tecumseh was perhaps the fifth of at least eight children.[6] Tecumseh's parents met and married in what is now Alabama, where part of the Shawnee tribe had settled after being driven out of the Ohio County by the Iroquois in the 17th century Beaver Wars. Around 1759, Puckeshinwau and Methoataaskee moved to the Ohio County as part of a Shawnee effort to reunite in their traditional homeland.[7]

In 1763, the British Empire laid claim to the Ohio Country following its victory in the French and Indian War. That year, Puckeshinwau took part in Pontiac's War, a multi-tribal effort to counter British control of the region.[8] Tecumseh was born in the peaceful decade after Pontiac's War, a time in which Puckeshinwau likely became the chief of Kispoko town on the Scioto.[9] In a 1768 treaty, the Iroquois ceded land south of the Ohio River (including present Kentucky) to the British, a region the Shawnee and other tribes used for hunting. Shawnees attempted to organize a multi-tribal resistance against colonial occupation of the region, culminating in the 1774 Battle of Point Pleasant, in which Puckeshinwau was killed. After the battle, Shawnees ceded Kentucky to the American colonists.[10][11]

When the American Revolutionary War began in 1775, many Shawnees allied themselves with the British, raiding into Kentucky in an effort to drive out the American colonists. [12] Tecumseh, too young to fight, was among those forced to relocate in the face of American counterraids. General George Rogers Clark, commander of the Kentucky militia, led a major expedition into Shawnee territory in 1780. Tecumseh may have witnessed the ensuing Battle of Piqua on August 8. After the Shawnees retreated, Clark burned their villages and crops. The Shawnees relocated to the northwest, along Great Miami River, but Clark returned in 1782 and destroyed those villages as well, forcing the Shawnees to retreat further north, near present Bellefontaine, Ohio.[13]

From warrior to chief

After the American Revolutionary War, the United States claimed the lands north of the Ohio River by right of conquest. In response, Indians convened a great intertribal conference at Lower Sandusky in the summer of 1783. Speakers, most notably Joseph Brant (Mohawk), argued that Indians must unite to hold onto their lands. They put forth a doctrine that Indian lands were held in common by all tribes, and so no further land should be ceded to the United States without the consent of all the tribes. This idea made a strong impression on Tecumseh, just fifteen years old when he attended the conference. As an adult, he would become such a well-known advocate of this policy that some mistakenly thought it had originated with him.[14] The United States, however, insisted on dealing with the tribes individually, getting each to sign separate land treaties. In January 1786, Moluntha, the Shawnee head civil chief, signed the Treaty of Fort Finney, surrendering most of Ohio to the Americans.[15] Later that year, Moluntha was murdered by a Kentucky militiaman, initiating a new border war.[16]

Tecumseh, now about eighteen years-old, became a warrior under the tutelage of his older brother Cheeseekau.[17][18] Tecumseh participated in attacks on flatboats traveling down the Ohio River, carrying waves of immigrants into lands the Shawnees had lost. He was disturbed by the sight of prisoners being cruelly treated by the Shawnees, an early indication of his lifelong aversion to torture and cruelty for which he would later be celebrated.[19][20] In 1788, Tecumseh, Cheeseekau and their family moved westward, relocating near Cape Girardeau, Missouri. They hoped to be free of American settlers, only to find colonists moving there as well, so they did not stay long.[21]

In late 1789 or early 1790, Tecumseh traveled south with Cheeseekau to live with the Chickamauga Cherokees near Lookout Mountain in what is now Tennessee. Some Shawnees already lived among the Chickamaugas, who were fierce opponents of U.S. expansion. Cheeseekau led about forty Shawnees in raids against colonists; Tecumseh was presumably among them.[22] During his nearly two years among the Chickamaugas, Tecumseh probably had a daughter with a Cherokee woman; the relationship was brief and the child remained with her mother.[23]

In 1791, Tecumseh returned to the Ohio Country to take part in the Northwest Indian War as a minor war chief. He was inspired by the Indian confederacy that had been formed to fight the war, which provided a model for the confederacy he created years later.[24] He led a band of eight followers, including his younger brother Lalawéthika, later known as Tenskwatawa. Tecumseh missed fighting in a major Indian victory (St. Clair's defeat) on November 4 because he was hunting or scouting at the time.[25][26] The following year he took part in other skirmishes before rejoining Cheeseekau in Tennessee.[27] Tecumseh was with Cheeseekau when he was killed in an unsuccessful attack on Buchanan's Station near Nashville.[28] Tecumseh probably sought revenge for his brother's death, but the details are unknown.[29]

Tecumseh returned to the Ohio Country at the end of 1792 and fought in several more skirmishes.[30] In 1794, he fought in the Battle of Fallen Timbers, a bitter defeat for the Indians.[31][32] The Indian confederacy fell apart, especially after Blue Jacket, the most prominent Shawnee in the confederacy, agreed to make peace with the Americans.[33] Tecumseh did not attend the signing of the Treaty of Greenville (1795), in which about two-thirds of Ohio and portions of present-day Indiana were ceded to the United States.[34]

By 1796, Tecumseh was both the civil and war chief of a Kispoko band of about 50 warriors and 250 people.[35] His sister Tecumapease was the band's principal female chief. Tecumseh took a wife, Mamate, and had a son, Paukeesaa, born about 1796. Their marriage did not last, and Tecumapese raised Paukeesaa from the age of seven or eight.[36] Tecumseh's band moved to various locations before settling in 1798 close to Delaware Indians, along the White River near present Anderson, Indiana, where he lived for the next eight years.[37] He married twice more during this time. His third marriage, to White Wing, lasted until 1807.[38]

Rise of the Prophet

While Tecumseh lived along the White River, Indians in the region were troubled by sickness, alcoholism, poverty, the loss of land, depopulation, and the decline of their traditional way of life.[39] A number of religious prophets emerged, each offering explanations and remedies for the crisis. Among these was Tecumseh's younger brother Lalawéthika, a healer in Tecumseh's village.[40] Until this time, Lalawéthika had been regarded as a misfit with little promise.[41][40][42] In 1805, he began preaching, drawing upon ideas espoused by earlier prophets, particularly the Delaware prophet Neolin.[43] Lalawéthika urged listeners to reject European influences, stop drinking alcohol, and discard their traditional medicine bags.[44][45]

In 1806, Tecumseh and Lalawéthika, now known as the Shawnee Prophet, relocated to Greenville, Ohio, where followers built a village that attracted converts from multiple tribes. The Prophet's message spread widely; many people came to Greenville and it was difficult to feed them all.[46][47] Tecumseh hoped to reunite the scattered Shawnees at Greenville, but he was opposed by Shawnee Chief Black Hoof, who urged Shawnees to accommodate the United States by adopting some American customs.[48] Important converts who joined the movement at Greenville were Blue Jacket, the famed Shawnee war leader, and Roundhead (Wyandot), who became Tecumseh's close friend and ally.[49]

American settlers grew uneasy as Indians flocked to Greenville. In 1806 and 1807, Tecumseh and Blue Jacket traveled to Chillicothe, the capital of the new U.S. state of Ohio, to reassure the governor that Greenville posed no threat.[50] Rumors of war between the United States and Great Britain followed the Chesapeake incident of June 1807. To escape the rising tensions, Tecumseh and the Prophet decided to move west to a more secure location, further from American forts and closer to potential western Indian allies.[51][52]

In 1808, Tecumseh and the Prophet established a village Americans would call Prophetstown, north of present-day Lafayette, Indiana. The Prophet adopted a new name, Tenskwatawa ("The Open Door"), meaning he was the door through which followers could reach salvation.[53][54] Like Greenville, Prophetstown attracted numerous followers, comprising Shawnees, Potawatomis, Kickapoos, Winnebagos, Sauks, Ottawas, Wyandots, and Iowas.[55] Perhaps 6,000 people settled in area, making it larger than any American city in the region.[56] Jortner (2011) argues that Prophetstown was effectively an independent city-state.[57]

At Prophetstown, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa initially worked to maintain a peaceful coexistence with the United States.[58][59] A major turning point came in September 1809, when William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, negotiated the Treaty of Fort Wayne, purchasing 2.5 to 3 million acres (10,000 to 12,000 km2) of land in what is present-day Indiana and Illinois. Although many Indian leaders signed the treaty, many who used the land were deliberately excluded from the negotiations.[60] The treaty created widespread outrage among Indians, and "put Tecumseh on the road to war" with the United States.[61]

Forming a confederacy

Before the Treaty of Fort Wayne, Tecumseh was relatively unknown to outsiders, who usually referred to him as "the Prophet's brother."[61] Afterwards he emerged as a prominent figure as he built an intertribal confederacy to counter U.S. expansion.[62] In August 1810, Tecumseh met with William Henry Harrison at Vincennes, capital of the Indiana Territory, a standoff that became legendary.[63] Tecumseh demanded that Harrison rescind the Fort Wayne cession, and promised he would oppose American settlement on the disputed lands. He said the chiefs who had signed the treaty would be punished, and that he was uniting the tribes to prevent further cessions.[63][64] Harrison insisted the land had been purchased fairly and that Tecumseh had no right to object because Indians did not own land in common. Harrison said he would send Tecumseh's demands to President James Madison, but did not expect the president to accept them. As the meeting concluded, Tecumseh said that if Madison did not rescind the Fort Wayne treaty, "you and I will have to fight it out."[65][66]

After the confrontation with Harrison, Tecumseh traveled widely to build his confederacy.[67] He went westward to recruit allies among the Potawatomis, Winnebagos, Sauks, Foxes, Kickapoos, and Missouri Shawnees.[68] In November 1810, he visited Fort Malden in Upper Canada to ask British officials for assistance in the coming war, but the British were noncommittal, urging restraint.[69][70] In May 1811, Tecumseh visited Ohio to recruit warriors among the Shawnees, Wyandots, and Senecas.[71] After returning to Prophetstown, he sent a delegation to the Iroquois in New York.[72]

In July 1811, Tecumseh again met Harrison at Vincennes. He told the governor he had amassed a confederacy of northern tribes and was heading south to do the same. For the next six months, Tecumseh traveled some 3,000 miles (4,800 km) in the south and west to recruit allies. The documentary evidence of this journey is fragmentary, and was exaggerated in folklore, but he probably met with Chickasaws, Choctaws, Creeks, Osages, western Shawnees and Delawares, Iowas, Sauks, Foxes, Sioux, Kickapoos, and Potawatomis.[73] He was aided in his efforts by two extraordinary events: the Great Comet of 1811 and the New Madrid earthquake, which he and other Indians interpreted as omens that his confederacy should be supported.[74] Many rejected his overtures, especially in the south; his most receptive southern listeners were among the Creeks. A faction among the Creeks, who became known as the Red Sticks, responded to Tecumseh's call to arms, contributing to the coming of the Creek War.[75][76][77]

According to Sugden (1997), Tecumseh had made a "serious mistake" by informing Harrison he would be absent from Prophetstown for an extended time.[78] Harrison wrote that Tecumseh's absence "affords a most favorable opportunity for breaking up his Confederacy."[79] In September 1811, Harrison marched toward Prophetstown with about 1,000 men.[80] In the pre-dawn hours on November 7, warriors from Prophetstown launched a surprise attack on Harrison's camp, initiating the Battle of Tippecanoe. Harrison's men held their ground, after which the Prophet's warriors withdrew and evacuated Prophetstown. The Americans burned the village the following day and returned to Vincennes.[81]

Historians have traditionally viewed the Battle of Tippecanoe as a devastating blow to Tecumseh's confederacy. According to a story recorded by Benjamin Drake ten years after the battle, Tecumseh was furious with Tenskwatawa after the battle and threatened to kill him.[82] Afterwards, it was said, the Prophet played little part in the confederacy's leadership. Modern scholarship has cast doubt on this interpretation. Dowd (1992), Cave (2002), and Jortner (2011) argued that stories of Tenskwatawa's disgrace originated with Harrison's allies and are not supported by other sources.[83][84][85] According to this view, the battle was a setback for Tenskwatawa, but he continued to serve as the confederacy's spiritual leader, with Tecumseh as its diplomat and military leader.[86][87][88]

Harrison hoped his preemptive strike would subdue Tecumseh's confederacy, but a wave of frontier violence erupted after the battle. Indians, many who had fought at Tippecanoe, sought revenge, killing as many as 46 Americans.[89] Tecumseh sought to restrain warriors from premature action while preparing the confederacy for future hostilities.[90] By the time the United States declared war on Great Britain in June 1812, as many as 800 warriors had gathered around the rebuilt Prophetstown. Tecumseh's Indian allies throughout the Northwest Territory numbered around 3,500 warriors.[91]

War of 1812

In June 1812, Tecumseh arrived at Fort Malden in Amherstburg to join his cause with the British war effort. The British recognized him as the most influential of their Indian allies and relied upon him to direct the Indian forces.[92] He and his warriors scouted and probed enemy positions as American General William Hull crossed into Canada, threatening to take Fort Malden. On July 25, Tecumseh's warriors skirmished with Americans north of Amherstburg, inflicting the first American fatalities of the war.[93]

Tecumseh turned his attention to cutting off Hull's supply and communication lines on the U.S. side of the border, south of Detroit. On August 5, he led 25 warriors in two successive ambushes, scattering a far superior force. Tecumseh captured Hull's outgoing mail, which revealed that the general was fearful of being cut off. On August 9, Tecumseh joined with British soldiers at the Battle of Maguaga, successfully thwarting Hull's attempt to reopen his line of communications. Two days later, Hull pulled the last of his men from Amherstburg, ending his attempt to invade Canada.[94][95]

On August 13, Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, British commander of Upper Canada, arrived at Fort Malden and began preparations for attacking Hull at Fort Detroit. Tecumseh, upon hearing of Brock's plans, reportedly turned to his companions and said, "This is a man!"[96][97][note 1] Tecumseh led about 530 warriors in the Siege of Detroit.[98] According to one account, Tecumseh had his warriors repeatedly pass though an opening in the woods to create the impression that thousands of Indians were outside the fort, a story that may apocryphal.[99][note 2] To almost everyone's astonishment, Hull decided to surrender on August 16.[100] Afterwards, Brock wrote of Tecumseh: "A more sagacious or a more gallant warrior does not I believe exist."[101][102]

Fort Meigs

After the capture of Detroit, Tecumseh returned to the Prophetstown region to coordinate Indian war efforts.[103] Meanwhile, the Americans, having suffered defeat at the Battle of Frenchtown in January 1813, were pushing back toward Detroit under the command of William Henry Harrison. Tecumseh returned to Amhersburg in April 1813, then he and Roundhead led about 1,200 warriors to Fort Meigs, a recently constructed American fort along the Maumee River. The Indians initially saw little action while British forces under General Henry Procter laid siege to the fort. Fighting outside the fort began on May 5 after the arrival of American reinforcements, who attacked the British gun batteries. Tecumseh led an attack on an American sortie from the fort, then crossed the river to help defeat a regiment of Kentucky militia.[104] The British and Indians had inflicted heavy casualties on the Americans outside the fort, but failed to capture it. Procter's Canadian militia and many of Tecumseh's warriors left after the battle, so they were compelled to lift the siege.[105][106][107]

One of the most famous incidents in Tecumseh's life occurred after the battle.[108] American prisoners had been taken to the nearby ruins of Fort Miami. When a group of Indians began killing prisoners, Tecumseh rushed in and stopped the slaughter. According to Sugden (1997), "Tecumseh's defense of the American prisoners became a cornerstone of his legend, the ultimate proof of his inherent nobility."[109] Some accounts said Tecumseh rebuked General Procter for failing to protect the prisoners, though this might not have happened.[110]

Tecumseh and Procter returned to Fort Meigs in July 1813, Tecumseh with 2,500 warriors, the largest contingent he would ever lead.[111] They had little hope of taking the strongly defended fort, but Tecumseh sought to draw the Americans into open battle. He staged a mock battle within earshot of the fort, hoping the Americans would ride out to assist. The ruse failed and the second siege of Fort Meigs was lifted.[112][113][114] Procter then led a detachment to attack Fort Stephenson on the Sandusky River, while Tecumseh went west to intercept potential American advances. Procter's attack failed and the expedition returned to Amherstburg.[115][116]

Death and aftermath

Tecumseh hoped further offensives were forthcoming, but after the American victory in the Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813, Procter decided to retreat from Amherstburg.[117][118] Tecumseh pleaded with Procter to stay and fight: "Our lives are in the hands of the Great Spirit. We are determined to defend our lands, and if it is his will, we wish to leave our bones upon them."[119] Procter insisted the defense of Amherstburg was untenable, but he promised to make a stand at Chatham, along the Thames River.[120][121] Tecumseh reluctantly agreed. The British burned Fort Malden and public buildings in Amherstburg, then began the retreat, with William Henry Harrison's American army in pursuit.[121][122]

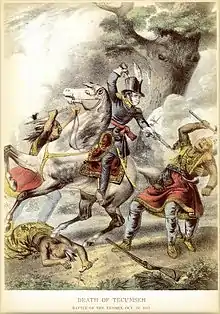

Tecumseh arrived at Chatham to find that Procter had retreated even further upriver. Procter sent word that he had chosen to make a stand near Moraviantown. Tecumseh was angered by the change in plans, but he led a rearguard action at Chatham to slow the American advance, and was slightly wounded in the arm.[122] Many of Tecumseh's despairing allies deserted during the retreat, leaving him 500 warriors.[122] Procter and Tecumseh, outnumbered more than three-to-one, faced the Americans at the Battle of the Thames on October 5. Tecumseh positioned his men in a line of trees along the right, hoping to flank the Americans.[123] The left, commanded by Procter, collapsed almost immediately, and Procter fled the field.[124] Colonel Richard Mentor Johnson led the American charge against the Indians. Tecumseh was killed in the fierce fighting, and the Indians dispersed. The Americans had won a decisive victory.[125][126][127]

After the battle, American soldiers stripped and scalped Tecumseh's body. The next day, when Tecumseh's body had been positively identified, others peeled off some skin as souvenirs.[128] The location of his remains are unknown.[note 3] The earliest account stated that his body had been taken by Canadians and buried at Sandwich.[129] Later stories said he was buried at the battlefield, or that his body was secretly removed and buried elsewhere.[130] According to another tradition, an Ojibwe named Oshahwahnoo, who had fought at Moraviantown, exhumed Tecumseh's body in the 1860s and buried him on St. Anne Island on the St. Clair River.[131] In 1931, these bones were examined. Tecumseh had broken a thighbone in a riding accident as a youth and thereafter walked with a limp, but neither thigh of this skeleton had been broken. Nevertheless, in 1941 the remains were buried on nearby Walpole Island in a ceremony honoring Tecumseh.[132]

Initial published accounts identified Richard Mentor Johnson as having killed Tecumseh. In 1816, another account claimed a different soldier had fired the fatal shot.[133] The matter became controversial in the 1830s when Johnson was a candidate for national office. Johnson's supporters promoted him as Tecumseh's killer, employing slogans such as "Rumpsey dumpsey, Colonel Johnson killed Tecumseh." Johnson's opponents collected testimony contradicting this claim; numerous other possibilities were named. Sugden (1985) presented the evidence and argued that Johnson's claim was the strongest, though not conclusive.[134] Johnson became Vice President of the United States in 1837, his fame largely based on his claim to have killed Tecumseh.[135]

Tecumseh's death led to the collapse of his confederacy; except in the southern Creek War, most of his followers did little more fighting.[136][137] In the negotiations that ended the War of 1812, the British attempted to honor promises made to Tecumseh by insisting upon the creation of an Indian buffer state in the Old Northwest. The Americans refused and the matter was dropped.[138][139] The Treaty of Ghent (1814) called for Indian lands to be restored to their 1811 boundaries, something the United States had no intention of doing.[140] By the end of the 1830s, the U.S. government had compelled the Shawnee groups still living in Ohio to sign removal treaties and move west of the Mississippi River.[141]

Legacy

Tecumseh was widely admired in his lifetime, even by Americans who had fought against him.[142] His primary American foe, William Henry Harrison, described Tecumseh as "one of those uncommon geniuses, which spring up occasionally to produce revolutions and overturn the established order of things."[143] After his death, he became an iconic folk hero in American, Indigenous, and Canadian history.[144][145] For many Native Americans in the United States and First Nations people in Canada, he became a hero who transcends tribal identity.[146] Tecumseh's stature grew over the decades after his death, often at the expense of Tenskwatawa, whose religious view white writers found alien and off putting. White writers tended to turn Tecumseh into a "secular" leader who only used his brother's religious movement for political reasons. For Europeans and white North Americans, he became the foremost example of the "noble savage" stereotype.[147][148]

Tecumseh is honored in Canada as a hero who played a major role in Canada's defense in the War of 1812. John Richardson, an important early Canadian novelist, had served with Tecumseh and idolized him. His 1828 epic poem "Tecumseh; or, The Warrior of the West" was intended to "preserve the memory of one of the noblest and most gallant spirits" in history.[149] Canadian writers such as Charles Mair (Tecumseh: A Drama, 1886) celebrated Tecumseh as a Canadian patriot, an idea reflected in numerous subsequent biographies written for Canandian school children.[149] Among the many things named for Tecumseh in Canada are the naval reserve unit HMCS Tecumseh and Tecumseh, Ontario.[150]

Tecumseh has long been admired in Germany, due especially to popular novels by Fritz Steuben, beginning with The Flying Arrow (1930).[151] Steuben used Tecumseh to promote Nazi ideology, though later editions of his novels removed the Nazi elements.[152] An East German film, Tecumseh (1972), starred Gojko Mitić in the title role.[152]

In the United States, Tecumseh has been featured in numerous poems, plays, and novels, as well as several movies and outdoor dramas. Examples include George Jones's Tecumseh; or, The prophet of the West (1844 play),[153] Mary Catherine Crowley's Love Thrives in War (1903 novel),[154] Brave Warrior (1952 film),[155] and Allan W. Eckert's A Sorrow in Our Hearts: The Life of Tecumseh (1992 novel).[154] James Alexander Thom's 1989 novel Panther in the Sky was made into a TV movie, Tecumseh: The Last Warrior (1995).[156] The outdoor drama Tecumseh! has been performed near Chillicothe, Ohio, since 1973. Written by Allan Eckert, the story features a fictional romance between Tecumseh and a white settler woman.[157][158]

References

Notes

- This oft-quoted comment was reported by a member of Brock's regiment who was not present; Sudgen writes, "perhaps it happened."[96]

- This incident was reported by a Canadian militia officer who was not an eyewitness; American accounts of the battle do not mention it.[99]

- For a detailed account of the mystery of Tecumseh's resting place, see Guy St-Denis, Tecumseh's Bones (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2005).

Citations

- Sugden 1997, p. 22.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 22, 415n19.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 14, 23.

- Cozzens 2020, p. 445n14.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 13–14.

- Edmunds 2007, p. 17.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 16–19.

- Sugden 1997, p. 19.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 20–22.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 25–29.

- Edmunds 2007, pp. 16, 18.

- Sugden 1997, p. 30.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 35–36.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 42–44.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 44–45.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 46–47.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 48–49, 75.

- Edmunds 2007, p. 21.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 51–52.

- Edmunds 2007, p. 23.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 54–55.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 57–59.

- Sugden 1997, p. 61.

- Sugden 1997, p. 81.

- Sugden 1997, p. 63.

- Edmunds 2007, p. 30.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 64–66.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 73–75.

- Sugden 1997, p. 76.

- Sugden 1997, p. 82–86.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 87–90.

- Edmunds 2007, pp. 36–37.

- Sugden 1997, p. 91.

- Sugden 1997, p. 92.

- Sugden 1997, p. 94.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 98–99.

- Sugden 1997, p. 100.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 102–03.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 103–10.

- Sugden 1997, p. 113.

- Cayton 1996, pp. 205–09.

- Edmunds 2007, pp. 69–71.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 119–20.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 117–19.

- Cave 2002, pp. 642–43.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 143–48.

- Edmunds 2007, pp. 85–86.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 128–31.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 131–33.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 3–8, 136.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 156–57, 160, 167.

- Willig 1997, p. 127.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 168.

- Cave 2002, p. 643.

- Willig 1997, p. 128.

- Jortner 2011, p. 145.

- Jortner 2011, pp. 145–47.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 168–74.

- Cave 2002, p. 647.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 182–84.

- Sugden 1997, p. 187.

- Edmunds 2007, p. 111.

- Sugden 1997, p. 198.

- Edmunds 2007, pp. 118–19.

- Sugden 1997, p. 202.

- Edmunds 2007, p. 121.

- Sugden 2000, p. 167.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 205–11.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 212–14.

- Edmunds 1983, p. 98.

- Sugden 1997, p. 217.

- Sugden 1997, p. 218.

- Sugden 1986, p. 298.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 246–51.

- Sugden 1986, p. 299.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 262–63.

- Edmunds 2007, pp. 133–39.

- Sugden 1997, p. 224.

- Edmunds 2007, p. 140.

- Edmunds 1983, pp. 104–06.

- Edmunds 1983, pp. 111–14.

- Dowd 1992, pp. 324–25.

- Dowd 1992, pp. 322–24.

- Cave 2002, pp. 657–64.

- Jortner 2011, p. 198.

- Dowd 1992, p. 327.

- Cave 2002, pp. 663–67.

- Jortner 2011, p. 199.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 258–61.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 262–71.

- Sugden 1997, p. 273.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 279–83.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 288–89.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 295–97.

- Gilpin 1958, pp. 96–98, 100–04.

- Sugden 1997, p. 300.

- Gilpin 1958, p. 105.

- Sugden 1997, p. 301.

- Sugden 1997, p. 303.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 303–05.

- Sugden 1997, p. 311.

- Antal 1997, p. 105.

- Edmunds 2007, p. 174.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 331–34.

- Gilpin 1958, pp. 189–90.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 338–39.

- Edmunds 2007, p. 179.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 334–35.

- Sugden 1997, p. 338.

- Sugden 1997, p. 337.

- Sugden 1997, p. 347.

- Gilpin 1958, pp. 204–05.

- Hickey 1989, p. 136.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 347–48.

- Sugden 1997, p. 348.

- Gilpin 1958, pp. 206–07.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 356–57.

- Gilpin 1958, pp. 214–16.

- Sugden 1997, p. 360.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 360–61.

- Gilpin 1958, p. 217.

- Sugden 1997, p. 363.

- Sugden 1997, p. 369.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 372–73.

- Gilpin 1958, pp. 223–26.

- Sugden 1997, p. 374.

- Hickey 1989, p. 139.

- Sugden 1997, p. 379.

- Sugden 1997, p. 380.

- Sugden 1985, pp. 215–18.

- Sugden 1985, p. 218.

- Sugden 1985, p. 220.

- Sugden 1985, p. 138.

- Sugden 1985, pp. 136–67.

- Sugden 1997, p. 375.

- Edmunds 2007, pp. 197–98.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 383–86.

- Sugden 1997, p. 383.

- Calloway 2007, p. 153.

- Allen 1993, p. 169.

- Calloway 2007, pp. 155–66.

- Edmunds 2007, p. 205.

- Edmunds 2007, pp. 205-06.

- Sugden 1997, pp. 389–90.

- Bumsted 2009, p. 244.

- Sugden 1997, p. 390.

- Edmunds 2007, p. 207.

- Sugden 1997, p. 396.

- Sugden 1997, p. 392.

- Sugden 1997, p. 391.

- Sugden 1997, p. 393.

- Sugden 1997, p. 394.

- Sugden 1997, p. 397.

- Sugden 1997, p. 399.

- Sugden 1997, p. 395.

- Sugden 1997, p. 456.

- Edmunds 2007, p. 201.

- Barnes 2017.

Sources

- Allen, Robert S. (1993). His Majesty's Indian Allies: British Indian Policy in the Defence of Canada 1774–1815. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-55488-189-5.

- Antal, Sandy (1997). A Wampum Denied: Procter's War of 1812. United States: Carleton University Press. ISBN 0-87013-443-4.

- Barnes, Benjamin J. (2017). "Becoming our Own Storytellers: Tribal Nations Engaging with Academia". In Warren, Stephen (ed.). The Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma: Resilience Through Adversity. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806161006.

- Bumsted, J. M. (2009). The Peoples of Canada: a Pre-Confederation History. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195431018.

- Calloway, Colin G. (2007). The Shawnees and the War for America. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-03862-6.

- Cave, Alfred A. (2002). "The Shawnee Prophet, Tecumseh, and Tippecanoe: A Case Study of Historical Myth-Making". Journal of the Early Republic. 22 (4): 637–673. JSTOR 3124761. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- Cayton, Andrew R. L. (1996). Frontier Indiana. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253330483.

- Cozzens, Peter (2020). Tecumseh and the Prophet: The Shawnee Brothers Who Defied a Nation. United States: Knopf. ISBN 9781524733254.

- Dowd, Gregory E. (1992). "Thinking and Believing: Nativism and Unity in the Ages of Pontiac and Tecumseh". American Indian Quarterly. 16 (3): 309–335. JSTOR 1185795. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- Edmunds, R. David (1983). The Shawnee Prophet. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1850-8.

- Edmunds, R. David (2007). Tecumseh and the Quest for Indian Leadership (2nd ed.). New York: Pearson Longman. ISBN 9780321043719.

- Gilpin, Alec R. (1958). The War of 1812 in the Old Northwest. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 9781628961270.

- Goltz, Herbert C. W. (1983). "Tecumseh". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. V (1801–1820) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Hickey, Donald R. (1989). The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. Urbana; Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01613-0.

- Jortner, Adam (2011). The Gods of Prophetstown: The Battle of Tippecanoe and the Holy War for the American Frontier. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199765294.

- Owens, Robert M. (2007). Mr. Jefferson's Hammer: William Henry Harrison and the Origins of American Indian Policy. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3842-8.

- Sugden, John (1985). Tecumseh's Last Stand (hardcover ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-80611-944-6.

- Sugden, John (1986). "Early Pan-Indianism: Tecumseh's Tour of the Indian Country, 1811-1812". American Indian Quarterly. 10 (4): 273–304. doi:10.2307/1183838. JSTOR 1183838. (essay later included in Nichols, Roger L. (ed) (1992). The American Indian: Past and Present. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. 107–129, ISBN 0-07-046499-5).

- Sugden, John (1997). Tecumseh: A Life (hardcover ed.). New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-4138-9. (Paperback Edition: 1999, ISBN 978-0-8050-6121-5)

- Sugden, John (2000). "Tecumseh's Travels Revisited". Indiana Magazine of History. 96 (2): 150–168. JSTOR 27792243. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- Willig, Timothy D (1997). "Prophetstown of the Wabash: The Native Spiritual Defense of the Old Northwest". Michigan Historical Review. 23 (2): 115–158. JSTOR 20173677. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

External links

- "Birthplace of Tecumseh". www.hmdb.org. Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved January 16, 2021. Modern scholarship has shown that this marker is probably in the wrong location.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tecumseh. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Tecumseh |