Ten (Pearl Jam album)

Ten is the debut studio album by American rock band Pearl Jam, released on August 27, 1991, through Epic Records. Following the disbanding of bassist Jeff Ament and guitarist Stone Gossard's previous group Mother Love Bone, the two recruited vocalist Eddie Vedder, guitarist Mike McCready, and drummer Dave Krusen to form Pearl Jam in 1990. Most of the songs began as instrumental jams, to which Vedder added lyrics about topics such as depression, homelessness, and abuse.

| Ten | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Artwork for the 1991 vinyl edition | ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | August 27, 1991 | |||

| Recorded | March 27 – April 26, 1991 | |||

| Studio | London Bridge, Seattle | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 53:20 | |||

| Label | Epic | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Pearl Jam chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Ten | ||||

Though a grunge record, Ten's musical style is influenced by classic rock and combines an "expansive harmonic vocabulary" with an anthemic sound.[1] While it deals with dark subject matter, it has generally been seen as a landmark of the early 1990s alternative rock sound, with Vedder's unusually deep and strong voice alternating between solidity and vibrato against the unrestrained, guitar-heavy, hard rock sound that drew influence from rock bands of the 1970s.

Ten was not an immediate success, but by late 1992 it had reached number two on the Billboard 200. The album produced three hit singles: "Alive", "Even Flow", and "Jeremy". "Jeremy" became one of Pearl Jam's best-known songs, and received nominations for Best Rock Song and Best Hard Rock Performance at the 35th Grammy Awards.[2] The video for "Jeremy" was heavily rotated by MTV, and received four awards at the 1993 MTV Video Music Awards, including Video of the Year and Best Group Video.[3]

Ten was instrumental in popularizing alternative rock in the mainstream[4] and has since been ranked by several publications as one of the greatest albums of all time. By February 2013, it had sold 13 million copies in the US, becoming the 22nd record to do so in the Nielsen SoundScan era[5] and has been certified 13× Platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). Ten remains Pearl Jam's most commercially successful album.[6]

Background

Guitarist Stone Gossard and bassist Jeff Ament had played together in the pioneering grunge band Green River. Following Green River's dissolution in 1987, Ament and Gossard played together in Mother Love Bone during the late 1980s. Mother Love Bone's career was cut short when vocalist Andrew Wood died of a drug overdose in 1990, shortly before the release of the group's debut album, Apple. Devastated, it took months before Gossard and Ament agreed to play together again. Gossard spent his time afterwards writing material that was harder-edged than what he had been doing previously.[7] After a few months, Gossard started practicing with fellow Seattle guitarist Mike McCready, whose band Shadow had broken up; McCready in turn encouraged Gossard to reconnect with Ament.[8] The three then went into the studio for separate sessions with Soundgarden drummer Matt Cameron and former Shadow drummer Chris Friel to record some instrumental demos.[9] Five of the songs recorded—"Dollar Short", "Agytian Crave", "Footsteps", "Richard's E", and "E Ballad"—were compiled onto a tape called Stone Gossard Demos '91 that was circulated in the hopes of finding a singer and drummer for the trio.[4]

San Diego musician Eddie Vedder acquired a copy of the demo in September 1990, when it was given to him by former Red Hot Chili Peppers drummer Jack Irons. Vedder listened to the demo, went surfing, and wrote lyrics the next day for "Dollar Short", "Agytian Crave", and "Footsteps". "Dollar Short" and "Agytian Crave" were later retitled "Alive" and "Once", respectively. Gossard and Ament heard the demo with Vedder's vocals and lyrics, and were impressed enough to fly Vedder out to Seattle for an audition. Meanwhile, Vedder had written lyrics for "E Ballad", retitled "Black". Vedder arrived on October 13, 1990 and rehearsed with the band (now joined by drummer Dave Krusen) for a week, writing eleven songs in the process. Vedder was soon hired as the band's singer, and the group signed to Epic Records shortly thereafter.[4]

Recording

The band, then named Mookie Blaylock, entered London Bridge Studios in Seattle, Washington in March 1991 with producer Rick Parashar to record its debut album. After working with Parashar on Temple of the Dog, Stone and Ament asked him to co-produce and engineer Ten. Parashar also contributed piano, Fender Rhodes, percussion, co-wrote vocal harmonies and co-wrote the intro/outro of the album. A few tracks were previously recorded at London Bridge in January, but only "Alive" was carried over from that session. The album sessions were quick and lasted only a month, mainly due to the band having already written most of the material for the record. "Porch", "Deep", "Why Go", and "Garden" were first recorded during the album sessions; everything else had been previously recorded during demo sessions at some point. McCready said that "Ten was mostly Stone and Jeff; me and Eddie were along for the ride at that time."[10] Ament stated, "We knew we were still a long way from being a real band at that point."[11]

The recording sessions for Ten were completed in May 1991. Krusen left the band once the sessions were completed, checking himself into rehab.[9] According to Krusen, he was suffering from personal problems at the time.[9] Krusen said, "It was a great experience. I felt from the beginning of that band that it was something special," and added, "They had to let me go. I couldn't stop drinking, and it was causing problems. They gave me many chances, but I couldn't get it together."[12] In June, the band joined Tim Palmer in England for mixing. Palmer decided to mix the album at Ridge Farm Studios in Dorking, a converted farm that according to Palmer was "about as far away from an L.A. or New York studio as you can get."[4] Palmer made a few additions to the already-recorded songs, including having McCready finish up the guitar solo on "Alive" and tweaking the intro to "Black". Palmer overdubbed a pepper shaker and a fire extinguisher as percussion on "Oceans".[4]

In subsequent years, band members have expressed dissatisfaction with the way the album's mixing turned out. In 2001, Ament said, "I'd love to remix Ten. Ed, for sure, would agree with me. It wouldn't be like changing performances; just pull some of the reverb off it."[10] In 2002, Gossard said, "It was 'over-rocked', we were novices in the studio and spent too long recording, doing different takes, and killing the vibe and overdubbing tons of guitar. There's a lot of reverb on the record."[13] In 2006, Vedder said, "I can listen to the early records [except] the first record...it's just the sound of the record. It was kind of mixed in a way that was...it was kind of produced."[14]

Music and lyrics

Ten has been described as a grunge,[1][15] alternative rock,[1][15] and hard rock album.[1] Several of the songs on the album started as instrumental compositions that Vedder added lyrics to after he joined the band. Regarding the lyrics, Vedder said, "All I really believe in is this fucking moment, like right now. And that, actually, is what the whole album talks about."[16] Vedder's lyrics for Ten deal with subjects like depression, suicide, loneliness, and murder. The album also tackles social concerns such as homelessness ("Even Flow")[17] and the use of psychiatric hospitals ("Why Go").[18] The song "Jeremy" and its accompanying video were inspired by a true story in which a high school student shot himself in front of his classmates.[19][20]

Many listeners interpreted "Alive" as an inspirational anthem due to its decidedly uplifting instrumentals and chorus. Vedder has since revealed that the song tells the semi-autobiographical tale of a son discovering that his father is actually his stepfather (his real father having died long ago), while his mother's grief turns her to sexually embrace her son, who strongly resembles the biological father.[7] "Alive" and "Once" formed part of a song cycle in what Vedder later described as a "mini-opera" entitled Momma-Son[21] (the third song, "Footsteps", appeared as a B-side on the "Jeremy" single). Vedder explained that the lyrics told the story of a young man whose father dies ("Alive"), causing him to go on a killing spree ("Once") which leads to his capture and execution ("Footsteps"). It was later revealed that Vedder's lyrics were inspired by his long-held hurt in discovering at age 17 that the man he thought was his father was not, and that his real father had already died.[4]

While Ten deals with dark subject matter, it has generally been seen as a high-water mark of the early 1990s alternative rock sound, with Vedder's unusually deep and strong (and later much-imitated) voice alternating between solidity and vibrato against the unrestrained, guitar-heavy, hard rock sound that drew influence from Led Zeppelin and other rock bands of the 1970s. Ten's musical style, influenced by classic rock, combined an "expansive harmonic vocabulary" with an anthemic sound.[1] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic stated that the songs on the album fused "the riff-heavy stadium rock of the 1970s with the grit and anger of '80s post-punk, without ever neglecting hooks and choruses."[22]

Ten features a two-part track entitled "Master/Slave" that both opens and closes the album. The first part begins the album, before "Once" starts, and the second part closes the album, after "Release". It begins about ten seconds after the album's closer "Release" as a hidden track, but both count as one track on the CD. The song is entirely instrumental (except for random unintelligible words Vedder utters throughout) with a dominant fretless bass line making up the core of the song (which Ament referred to in a 1994 Bass Player magazine interview as "my tribute to (fretless bass instrumentalist) Mick Karn"),[23] along with some guitar and sounds that seem to come from the drums. Producer Rick Parashar stated in 2002, "As I recall, I think Jeff had, like, a bass line...I heard the bass line and then we kind of were collaborating on that in the control room, and then I just started programming on the keyboard all this stuff; he was jamming with it and it just kind of came about like that."[4]

Outtakes

The album's singles featured two B-sides from the Ten recording sessions which were not included on the album, "Wash" and "Yellow Ledbetter". The former was a B-side on the "Alive" single while the latter was featured on the "Jeremy" single and eventually became a radio hit in 1994. Both songs were included on the 2003 Lost Dogs collection of rarities, although the included version of "Wash" is an alternate take. The song "Alone" was also originally recorded for Ten; a 1992 re-recorded version of the song is on the "Go" single. Another version of "Alone", with re-recorded vocals, appears on Lost Dogs.[24] According to McCready, "Alone" was cut from Ten because the band already had enough mid-tempo songs for the album.[24] The song "Dirty Frank", which was released as a B-side on the "Even Flow" single and often thought to be a Ten outtake, was recorded after Ten was released. Thus, "Dirty Frank" is not from the Ten recording sessions.[25]

The song "Footsteps" began as an instrumental demo and was compiled onto the Stone Gossard Demos '91 tape. Vedder added vocals to this version after he received the demo tape. The music for "Footsteps" was also used for Temple of the Dog's "Times of Trouble".[24] "Footsteps" was featured as a B-side on the "Jeremy" single, however this version is taken from a 1992 appearance on the radio show Rockline.[26] This version of "Footsteps" is also featured on Lost Dogs, however a harmonica intro has been overdubbed on to the recording.

Other songs rejected from the album but later included on Lost Dogs are "Hold On" and "Brother", the latter of which was turned into an instrumental for Lost Dogs.[24] "Brother" was cut because Gossard was no longer interested in playing the song, a decision which Ament objected to and almost caused him to quit the band.[27] The version of "Brother" with vocals appears on the 2009 Ten reissue and became a radio hit that same year.[28] Both "Breath" and "State of Love and Trust" were recorded with the intention of the two songs possibly appearing in the film Singles.[29] The versions heard in the film and on its soundtrack were recorded a year later in 1992.[30] The versions from the Ten sessions appear on the 2009 Ten reissue. Other songs rejected from the album but included on the 2009 Ten reissue are "Just a Girl", "2,000 Mile Blues", and "Evil Little Goat".

Release and promotion

Packaging

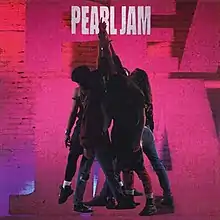

The album's cover art features the members of the band at the time of recording in a group pose and standing in front of a wood cut-out of the name "Pearl Jam", with their hands risen high and holding one another's. The wood cut-out was constructed by Ament.[31] Ament said, "The original concept was about really being together as a group and entering into the world of music as a true band...a sort of all-for-one deal."[32] Ament is credited for the album's artwork and art direction,[33] Lance Mercer receives credit for photography, and both Lisa Sparagano and Risa Zaitschek are credited for design.[33] Ament stated, "There was a bit of headbutting going on with the Sony art department at that time. The version that everybody got to know as the Ten album cover was pink and it was originally intended to be more of a burgundy color and the picture of the band was supposed to be black and white."[34] Pearl Jam's original name was taken from the professional basketball player Mookie Blaylock.[22] It was changed after the band signed to Epic Records, as record executives were concerned about intellectual property and naming rights following Blaylock's inking of an endorsement deal with Nike. In commemoration of the band's original name, the band titled its first album Ten after Blaylock's jersey number.[35]

In some versions, the cover is in gatefold form, folded in such a way that only the bandmembers' hands are visible.

Tour

Ament stated that "essentially Ten was just an excuse to tour", adding, "We told the record company, 'We know we can be a great band, so let's just get the opportunity to get out and play.'"[11] Pearl Jam faced a relentless touring schedule for Ten.[30] Drummer Dave Abbruzzese joined the band for Pearl Jam's live shows supporting the album. Halfway through its own planned North American tour, Pearl Jam cancelled the remaining dates in order to take a slot opening for the Red Hot Chili Peppers on the band's Blood Sugar Sex Magik tour in the fall of 1991 in North America. The spot was arranged by Jack Irons, who had called his former band asking for them to get an opportunity to his friend Vedder.[36] The Smashing Pumpkins and Nirvana were also supporting acts. Nirvana was initially brought in because the tour promoters decided that Pearl Jam should be replaced with a more successful act,[36] but the departure of The Smashing Pumpkins still kept the group in the concert bill.[36] Epic executive Michael Goldstone observed that "the band did such an amazing job opening the Chili Peppers tour that it opened doors at radio."[10]

In 1992, the band embarked on its first ever European tour. On March 13, 1992, at the Munich, Germany show at Nachtwerk, Pearl Jam played Ten in its entirety in order midway through its set.[37] The band would only do this again in 2016 at Philadelphia's Wells Fargo Center, as the arena management homaged the band's tenth straight sellout concert in the city.[38] Following the European leg, Pearl Jam did another tour of North America. Goldstone noted that the band's audience expanded, saying that unlike before, "everyone came."[10] The band's manager, Kelly Curtis, stated, "Once people came and saw them live, this lightbulb would go on. During their first tour, you kind of knew it was happening and there was no stopping it. To play in the Midwest and be selling out these 500 seat clubs. Eddie could say he wanted to talk to Brett, the sound guy, and they'd carry him out there on their hands. You hadn't really seen that reaction from a crowd before..."[10] When Pearl Jam came back for a second go-around in Europe the band appeared at the Pinkpop Festival and the Roskilde Festival in June 1992. The band cancelled its remaining European dates in the summer of 1992 after the Roskilde Festival due to a confrontation with security at that event as well as exhaustion from touring.[39] Ament said, "We'd been on the road over 10 months. I think there just came a point about half way through that tour it was just starting to get pretty intense. I mean just being away from home, being on the road all the time and being lonely or being depressed or whatever."[40] The band would go on to play the 1992 Lollapalooza tour with the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Soundgarden, Ministry and Ice Cube, among others.

2009 re-release

On March 24, 2009, Ten was reissued in four editions (Legacy, Deluxe, Vinyl, and Super Deluxe). It was the first reissue in a planned re-release of Pearl Jam's entire catalogue that led up to the band's 20th anniversary in 2011.[32] The extras on the four editions include a remastering and remix of the entire album by producer Brendan O'Brien, re-designed packaging, six bonus tracks ("Brother", "Just a Girl", "Breath and a Scream", "State of Love and Trust", "2,000 Mile Blues", and "Evil Little Goat"), a DVD of the band's 1992 appearance on MTV Unplugged (including a bonus performance of "Oceans", which along with "Rockin' in the Free World" was originally excluded from the broadcast version), vinyl versions of the album, an LP of the band's September 20, 1992 concert at Magnuson Park in Seattle (also known as Drop in the Park), a replica of the original Momma-Son demo cassette, and a replica of Vedder's composition notebook containing personal notes and mementos.

Regarding his remix of the album, O'Brien stated, "The band loved the original mix of Ten, but were also interested in what it would sound like if I were to deconstruct and remix it...The original Ten sound is what millions of people bought, dug and loved, so I was initially hesitant to mess around with that. After years of persistent nudging from the band, I was able to wrap my head around the idea of offering it as a companion piece to the original—giving a fresh take on it, a more direct sound."[32]

The Ten reissue sold 60,000 copies in its first week, the second biggest selling week for the album since Christmas 1993.[41] Since Billboard considers the Ten reissue a catalog item, Ten did not appear on the Billboard 200, Top Modern Rock/Alternative, or Top Rock Albums, since those charts do not include catalog items.[41] Had it been included on the Billboard 200, the 60,000 copies sold of the Ten reissue would have placed it at number five.[42] The reissue also re-entered the Australian Albums Chart at number 11, giving it a new peak chart position in Australia and its highest chart placing since June 14, 1992.[43]

Tying in with the re-release of the album, in March 2009, the entire album was made available as downloadable content for the Rock Band series of video games.[44] In addition, three Ten-era bonus tracks were made available for the Rock Band video game for those who purchased the Ten re-release through Best Buy: "Brother", "Alive", and "State of Love and Trust", the latter two as live versions taken from the band's September 20, 1992 concert.[45]

Critical reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Entertainment Weekly | B−[48] |

| Mojo | |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Uncut | |

| The Village Voice | B−[54] |

In a contemporary review for Rolling Stone, music critic David Fricke gave the album a favorable review, saying that Pearl Jam "hurtles into the mystic at warp speed." He also added that Pearl Jam "wring a lot of drama out of a few declarative power chords swimming in echo."[51] Allan Jones of Melody Maker suggested in his review of Ten that it is Vedder that "provides Pearl Jam with such a uniquely compelling focus."[55] AllMusic staff writer Steve Huey called it a "flawlessly crafted hard rock masterpiece" and felt that Vedder's "impressionistic lyrics" are more effective through his passionate vocal delivery rather than their "concrete meaning."[1] Q called it "raucous modern rock, spiked with infectious guitar motifs and powered with driving bass and drums," and said it "may well be the face of the 90's metal."[50] Stereo Review said that "the band sounds larger than life, producing a towering inferno of roaring guitars, monumental bass and drums, and from-the-gut vocals."[56] Don Kaye of Kerrang! defined the album "introspective and charged with a quiet emotional force".[57] Greg Kot wrote in the Chicago Tribune, "Occasionally overwrought and unrelentingly humorless, the music nonetheless exerts a hypnotic power at its best."[47]

In a less enthusiastic review for Entertainment Weekly, David Browne found Pearl Jam to be derivative of "fellow Northwestern rockers like Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, and the defunct Mother Love Bone", and felt that it "goes to show that just about anything can be harnessed and packaged."[48] NME accused Pearl Jam of "trying to steal money from young alternative kids' pockets."[58] Nirvana's Kurt Cobain angrily attacked Pearl Jam, claiming the band were commercial sellouts,[59] and argued Ten was not a true alternative album because it had so many prominent guitar leads.[4] Robert Christgau, writing in The Village Voice, gave the album a "B-" and viewed it as another in a "slew of Seattle albums" that "modulate the same misguided ethos", which he said was "hippie" rather than "punk". Christgau described it as "San Francisco ballroom music" whose "distinguishing characteristics" could only be discerned by listeners if they "take the right drugs".[54] He later gave Ten a two-star honorable mention, citing "Once" and "Even Flow" as highlights, and quipped, "in life, abuse justifies melodrama; in music, riffs work better".[60] Charles R. Cross wrote in The Rolling Stone Album Guide (2004) that Ten sounded less original and more self-important than Nirvana's Nevermind, but it also showcases the band's intricate guitar style and Vedder's distinctive singing.[52]

Accolades

Defined by Kerrang!'s George Garner as "arguably the greatest rock debut record of all time",[61] Ten, in 2003, was ranked number 207 on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time,[62] and 209 in a 2012 revised list. In 2020 it was raised to the 160th position on the list.[63] Readers of Q voted Ten as the 42nd greatest album ever;[64] however, three years later the album was listed lower at 59th.[65] In 2003, VH1 placed it at number 83 on their list of the 100 greatest albums of rock and roll.[66] In 2006, British Hit Singles & Albums and NME organised a poll of which, 40,000 people worldwide voted for the 100 best albums ever and Ten was placed at number 66 on the list.[67] It was also ranked number 15 in the October 2006 issue of Guitar World on the magazine's list of the 100 greatest guitar albums of all time.[68] In 2007, the album was included at number 11 on the list of the "Definitive 200" albums of all time developed by the National Association of Recording Merchandisers.[69] The album was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[70] In December 2020, the album was announced as one of many inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame as part of the 2021 class.[71]

| Publication | Country | Accolade | Year | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guitar World | United States | "100 Greatest Guitar Albums of All Time"[68] | 2006 | 15 |

| Rolling Stone | United States | "10 Greatest Debut Albums (Readers' Poll)"[72] | 2013 | 1 |

| National Association of Recording Merchandisers |

United States | "Definitive 200"[69] | 2007 | 11 |

| Pause & Play | United States | "The 90s Top 100 Essential Albums"[73] | 1999 | 11 |

| Q | United Kingdom | "100 Greatest Albums Ever"[64] | 2003 | 42 |

| Q | United Kingdom | "100 Greatest Albums Ever"[65] | 2006 | 59 |

| Rolling Stone | United States | "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time"[63][74] | 2012 | 209 |

| Spin | United States | "Top 90 Albums of the 90s"[75] | 1999 | 33 |

| Spin | United States | "100 Greatest Albums, 1985–2005"[76] | 2005 | 93 |

| VH1 | United States | "100 Greatest Albums of Rock & Roll"[66] | 2003 | 83 |

| Kerrang! | United Kingdom | "100 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die"[77] | 1998 | 15 |

| Nieuwe Revu | Netherlands | "Top 100 Albums of All Time"[78] | 1994 | 25 |

| Musik Express/Sounds | Germany | "The 100 Masterpieces"[79] | 1993 | 68 |

| Rolling Stone | Germany | "The 500 Best Albums of All Time"[80] | 2004 | 20 |

| Juice | Australia | "The 100 (+34) Greatest Albums of the 90s"[81] | 1999 | 101 |

| Viceversa | Italy | "100 Rock Albums"[82] | 1996 | 99 |

Commercial performance

Ten initially sold slowly upon its release, but by the second half of 1992 it became a breakthrough success, attaining an RIAA gold certification.[4] Almost a year after its release, the album finally broke into the top ten of the Billboard 200 album chart on May 30, 1992, reaching number eight. Ten would eventually peak at number two for four weeks. It was held off the top spot by the Billy Ray Cyrus album, Some Gave All.[83] The album spent a total of 264 weeks on the Billboard charts,[84] making it one of the top 15 charting albums ever. By February 1993, American sales of Ten surpassed those of Nevermind, the breakthrough album by fellow grunge band Nirvana.[85] Ten continued to sell well two years after its release; in 1993 it was the eighth best-selling album in the United States, outselling Pearl Jam's second album, Vs.[86] As of February 2013, Ten has sold 13 million copies in the United States according to Nielsen SoundScan,[5] and has been certified 13× platinum by the RIAA.[87]

Ten produced three hit singles, "Alive", "Even Flow", and "Jeremy", all of which had accompanying music videos (The "Oceans" video was released only outside of the U.S.). The singles all placed on the Mainstream Rock and Modern Rock charts. The song "Black" reached number three on the Mainstream Rock chart, despite never being released as a single. The video for "Alive" was nominated for the MTV Video Music Award for Best Alternative Video in 1992.[88] "Jeremy" became one of Pearl Jam's best-known songs, and received nominations for Best Rock Song and Best Hard Rock Performance at the 1993 Grammy awards.[2] The video for "Jeremy", directed by Mark Pellington, was put into heavy rotation by MTV and became a huge hit, receiving five nominations at the 1993 MTV Video Music Awards, of which it won four, including Video of the Year and Best Group Video.[3]

Track listing

Original release

All lyrics are written by Eddie Vedder; except for the bonus track "I've Got a Feeling", by John Lennon and Paul McCartney.

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Once" | Stone Gossard | 3:51 |

| 2. | "Even Flow" | Gossard | 4:53 |

| 3. | "Alive" | Gossard | 5:41 |

| 4. | "Why Go" | Jeff Ament | 3:20 |

| 5. | "Black" | Gossard | 5:43 |

| 6. | "Jeremy" | Ament | 5:18 |

| 7. | "Oceans" |

| 2:42 |

| 8. | "Porch" | Vedder | 3:30 |

| 9. | "Garden" |

| 4:59 |

| 10. | "Deep" |

| 4:18 |

| 11. | "Release[I]" |

| 9:05 |

| Total length: | 53:20 | ||

Note

- ^ "Release" contains the hidden track "Master/Slave" at 5:18.

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12. | "Alive" (live[I]) | Gossard | 4:54 |

| 13. | "Wash" |

| 3:33 |

| 14. | "Dirty Frank" |

| 5:38 |

| Total length: | 67:25 | ||

Note

- ^ *Recorded live on August 3, 1991 at RKCNDY in Seattle, Washington.

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12. | "I've Got a Feeling" | Lennon–McCartney | 3:42 |

| 13. | "Master/Slave" | Ament | 3:48 |

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12. | "Brother" (with vocals) | Gossard | 3:59 |

| 13. | "Just a Girl" (Mookie Blaylock demo 1990) | Gossard | 5:01 |

| 14. | "Breath and a Scream" (Mookie Blaylock demo 1990) | Gossard | 5:58 |

| 15. | "State of Love and Trust" (Demo 1991) |

| 4:47 |

| 16. | "2,000 Mile Blues" |

| 3:57 |

| 17. | "Evil Little Goat" |

| 1:27 |

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18. | "Why Go" (live at The Academy Theater) | Ament | 4:01 |

| 19. | "Even Flow" (live at The Academy Theater) | Gossard | 5:10 |

| 20. | "Alone" (live at The Academy Theater) |

| 3:26 |

| 21. | "Garden" (live at The Academy Theater) |

| 5:42 |

Note

MTV Unplugged DVD

- "Oceans"

- "State of Love and Trust"

- "Alive"

- "Black"

- "Jeremy"

- "Even Flow"

- "Porch"

Momma-Son cassette

All lyrics are written by Vedder; all music is composed by Gossard.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Alive" | 4:35 |

| 2. | "Once" | 3:44 |

| 3. | "Footsteps" | 4:20 |

Drop in the Park LP

All lyrics are written by Vedder.

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Even Flow" | Gossard | 5:14 |

| 2. | "Once" | Gossard | 3:32 |

| 3. | "State of Love and Trust" |

| 3:44 |

| 4. | "Why Go" | Ament | 3:20 |

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Deep" |

| 4:22 |

| 2. | "Jeremy" | Ament | 5:03 |

| 3. | "Black" | Gossard | 5:28 |

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Alive" | Gossard | 5:50 |

| 2. | "Garden" |

| 5:35 |

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Porch" | Vedder | 12:42 |

Personnel

Pearl Jam

- Stone Gossard – rhythm guitar, background vocals on "Why Go"

- Jeff Ament – bass guitar, art direction/concept, background vocals on "Why Go"

- Mike McCready – lead guitar

- Eddie Vedder – vocals, additional art

- Dave Krusen – drums, timpani

Additional musicians and production

- Dave Hillis – engineer

- Don Gilmore, Adrian Moore – additional engineering

- Walter Gray – cello

- Bob Ludwig – mastering

- Lance Mercer – photos

- Tim Palmer – fire extinguisher and pepper shaker on "Oceans", mixing

- Rick Parashar – production, piano, organ, percussion

- Pearl Jam – production

- Steve Pitstick – additional art

- Lisa Sparagano, Risa Zaitschek – design

- Kelly Curtis – management

Charts

Original release

2009 re-release

|

Year-end charts

Decade-end charts

|

Singles

| Single | Year | Peak chart positions | Certifications | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US [118] |

US Main [119] |

US Mod [120] |

AUS [121] |

BEL [122] |

CAN [123] |

GER [124] |

IRE [125] |

NLD [126] |

NZ [127] |

UK [128] | |||

| "Alive" | 1991 | —[upper-alpha 1] | 16 | 18 | 9 | 16 | — | 44 | 13 | 19 | 20 | 16 | |

| "Even Flow" | 1992 | —[upper-alpha 2] | 3 | 21 | 22 | — | 73 | — | — | — | 20 | 27 | |

| "Jeremy" | 79 | 5 | 5 | 68 | — | 32 | 93 | 10 | 59 | 34 | 15 |

| |

| "Oceans" | — | — | — | — | 35 | — | — | — | 30 | 16 | — | ||

| "—" denotes releases that did not chart or were not released in that territory. | |||||||||||||

- "Alive" did not enter the Billboard Hot 100, but spent 61 weeks on the Bubbling Under Hot 100 Singles chart, peaking at number 7.

- "Even Flow" did not enter the Billboard Hot 100, but spent 52 weeks on the Bubbling Under Hot 100 Singles chart peaking at number 8.

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[130] Re-release edition |

Gold | 20,000^ |

| Australia (ARIA)[131] | 7× Platinum | 490,000^ |

| Belgium (BEA)[132] | Platinum | 50,000* |

| Brazil (Pro-Música Brasil)[133] | Gold | 100,000* |

| Canada (Music Canada)[134] | 7× Platinum | 700,000^ |

| Denmark (IFPI Denmark)[135] | 3× Platinum | 60,000 |

| Germany (BVMI)[136] | Gold | 250,000^ |

| Italy (FIMI)[137] sales since 2009 |

Platinum | 100,000* |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[138] | 6× Platinum | 90,000^ |

| Norway (IFPI Norway)[139] | Gold | 25,000* |

| Poland (ZPAV)[140] | Gold | 50,000* |

| Sweden (GLF)[141] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[142] | Gold | 25,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[143] | 2× Platinum | 600,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[144] | 13× Platinum | 13,000,000^ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

- Huey, Steve. "Ten – Pearl Jam". AllMusic. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- "35th Grammy Awards". Rockonthenet. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- "1993 MTV Video Music Awards". Rockonthenet. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- Pearlman, Nina. "Black Days". Guitar World. December 2002.

- Keith Caulfield (February 20, 2013). "Pearl Jam's 'Ten' Album Hits 13 Million in U.S. Sales". Billboard. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- Paul Grein (December 12, 2012). "Week Ending Dec. 9, 2012. Albums: Swift's Birthday Present". Yahoo! Music. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- Crowe, Cameron (October 28, 1993). "Five Against the World". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 14, 2010. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- Hiatt, Brian (June 16, 2006). "The Second Coming of Pearl Jam". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 19, 2006. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- Greene, Jo-Ann. "Intrigue and Incest: Pearl Jam and the Secret History of Seattle (Part 2)". Goldmine. August 20, 1993.

- Weisbard, Eric, et al. "Ten Past Ten". Spin. August 2001.

- Coryat, Karl. "Godfather of the 'G' Word". Bass Player magazine. April 1994.

- Acrylic, Kim. "Interview with Dave Krusen of The Kings Royal". Punk Globe. January 2009.

- "Interview with Stone Gossard and Mike McCready". Total Guitar. November 2002.

- Hiatt, Brian. (June 20, 2006). "Eddie Vedder's Embarrassing Tale: Naked in Public". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 18, 2006. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

- "Which Pearl Jam Album Is the Best?". Spin. November 22, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- Neely, Kim. "Right Here, Right Now: The Seattle Rock Band Pearl Jam Learns How to Celebrate Life". Rolling Stone. October 31, 1991.

- Clay, Jennifer. "Life After Love Bone". RIP. December 1991.

- Vedder, Eddie. "Interview with David Sadoff" KLOL FM, Houston, Texas. December 1991. Retrieved on April 28, 2008.

- Miller, Bobbi. "Richardson Teen-ager Kills Himself in Front of Classmates". The Dallas Morning News. January 8, 1991.

- Plummer, Sean (September 28, 2011). "When music stars cross the line in their videos". MSN. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

- Pearl Jam (2011). Pearl Jam Twenty. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-84887-493-0.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Pearl Jam > Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved on June 22, 2007.

- Coryat, Karl. "Godfather of the 'G' Word". Bass Player Magazine. April 1994.

- Cohen, Jonathan. "The Pearl Jam Q & A: Lost Dogs". Billboard. 2003. Retrieved on May 9, 2008.

- "Even Flow: Information from". Answers.com. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- "Pearl Jam: 1992 Concert Chronology". FiveHorizons.com. Retrieved on April 30, 2008.

- (2003) Album notes for Lost Dogs by Pearl Jam, [CD booklet]. New York: Sony Music.

- "'Slumdog' Barks While Taylor Swift Nets 10th Week At No. 1". Billboard. February 25, 2009.

- Crowe, Cameron. "Making the Scene: A Filmmakers Diary". Rolling Stone. October 1, 1992. Retrieved on April 30, 2008.

- Gilbert, Jeff. "Alive & Kicking". Guitar World. September 1992.

- Brandolini, Chad. "Dave Krusen: Looking Back at Pearl Jam's Ten". Vater.com. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- Hay, Travis (December 10, 2008). "Pearl Jam's Ten gets the deluxe treatment with four reissues next year". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- "Ten: Credits at Allmusic". AllMusic. Retrieved on April 29, 2007.

- Quinn, Bryan. "Q+A session with Pearl Jam". Daily Record. March 9, 2009.

- Papineau, Lou. "20 Things You Should Know About Pearl Jam". VH1.com. June 30, 2006. Retrieved on April 30, 2008.

- Kiedis, Anthony; Sloman, Larry (October 6, 2004). Scar Tissue. Hyperion. ISBN 1-4013-0101-0.

- "Pearl Jam Shows: 1992 March 13, Nachtwerk Munich, Germany – Set List" Archived June 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. PearlJam.com. Retrieved on April 28, 2008.

- Kreps, Daniel (April 29, 2016). "Pearl Jam Perform 'Ten' in Its Entirety at Philadelphia Concert". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- "Pearl Jam: 1992 Concert Chronology: Part 2". FiveHorizons.com. Retrieved on April 28, 2008.

- Davis, Kathy. "Take the Whole Summer Off: TFT Looks Back at Lolla '92". TwoFeetThick.com. July 30, 2007. Retrieved on April 28, 2008.

- Trust, Gary (April 3, 2009). "Ask Billboard". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 5, 2009. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- Caulfield, Keith (April 1, 2009). "'Now 30,' 'Hannah' Lead Busy Week On Billboard 200". Billboard. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- Pearl Jam in Australian Charts. australian-charts.com. Retrieved on May 28, 2008.

- Faylor, Chris (December 14, 2008). "Rock Band Getting Full Pearl Jam Album". Shacknews. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- "Best Buy Exclusive" Archived March 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. BestBuy.com.

- Weiner, Jonah. "Pearl Jam: Ten". Blender. Archived from the original on December 28, 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- Kot, Greg (September 5, 1991). "Pearl Jam: Ten (Epic)". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- Browne, David (December 13, 1991). "Ten". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

- "Pearl Jam: Ten". Mojo (185): 116. April 2009.

- "Pearl Jam: Ten". Q (66): 79. March 1992.

- Fricke, David (December 12, 1991). "Pearl Jam: Ten". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 22, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2008.

- Cross, Charles R. (2004). "Pearl Jam". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 625–26. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- "Pearl Jam: Ten". Uncut. March 19, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- Christgau, Robert (December 1, 1992). "Turkey Shoot". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- Stud Brothers (June 20, 1992). "Eddie Vedder Takes On The World". Melody Maker.

- "Pearl Jam: Ten". Stereo Review: 80. January 1992.

- Kaye, Don (October 5, 1991). "Pearl Jam: Ten". Kerrang! (361).

- Gilbert, Jeff. "New Power Generation". Guitar World: Nirvana and the Seattle Sound. 1993.

- Al & Cake (May–June 1992). "An interview with...Kurt Cobain". Flipside.

- Christgau, Robert (October 15, 2000). Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s. Macmillan. p. 242. ISBN 0312245602.

- "Pearl Jam's Ten – The Evolution Of A Classic". Kerrang!. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- "207) Ten". Rolling Stone. November 2003. Retrieved on April 27, 2007.

- "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- "Q readers 100 Greatest Albums Ever". Q. January 2003.

- "Q Readers 100 Greatest Albums Ever". Q. February 2006.

- 100 greatest albums of rock & roll (100 - 81). VH1.com. Retrieved on April 29, 2007.

- "Oasis album voted greatest of all time". The Times. Jun 1, 2006

- "100 Greatest Guitar Albums of All Time Archived February 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine". Guitar World. October 2006.

- "Definitive 200". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. 2007.

- Robert Dimery; Michael Lydon (March 23, 2010). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN 978-0-7893-2074-2.

- "GRAMMY Hall Of Fame 2021 Inductions Announced". GRAMMY.com. December 21, 2020. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- "Readers' Poll: The Ten Greatest Debut Albums". Rolling Stone.

- "The 90s Top 100 Essential Albums". Pause and Play. Archived from the original on March 28, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- "Top 90 Albums of the 90s". Spin. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- "100 Greatest Albums, 1985-2005". Spin (July 2005).

- "100 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die". Kerrang!. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- "Top 100 Albums of All Time". Nieuwe Revu. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- "The 100 Masterpieces". Musik Express/Sounds. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- "The 500 Best Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- "The 100 (+34) Greatest Albums of the 90s". Juice. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- "100 Rock Albums". Viceversa. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- Scaggs, Austin. "Eddie Vedder: Addicted to Rock". Rolling Stone. April 21, 2006. Retrieved on June 30, 2008.

- https://www.billboard.com/artist/328459/pearl-jam/chart?f=305

- Snow, Mat. "You, My Son, Are Weird". Q. November 1993.

- Holden, Stephen. "The Pop Life". The New York Times. January 12, 1994. Retrieved on April 30, 2008.

- Gold and Platinum Database Search Archived July 19, 2012, at Archive.today. RIAA. Retrieved on February 12, 2007.

- "1992 MTV Video Music Awards". Rockonthenet. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- "Australiancharts.com – Pearl Jam – Ten". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Austriancharts.at – Pearl Jam – Ten" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Top Albums/CDs - Volume 56, No. 13, September 26, 1992". RPM. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- "Dutchcharts.nl – Pearl Jam – Ten" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- Pennanen, Timo (2006). Sisältää hitin - levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla vuodesta 1972 (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava. p. 263. ISBN 978-951-1-21053-5.

- "Longplay-Chartverfolgung at Musicline" (in German). Musicline.de. Phononet GmbH. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Charts.nz – Pearl Jam – Ten". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Norwegiancharts.com – Pearl Jam – Ten". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Swedishcharts.com – Pearl Jam – Ten". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Pearl Jam | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Pearl Jam Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Pearl Jam Chart History (Heatseekers Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Portuguesecharts.com – Pearl Jam – Ten". Hung Medien. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Ultratop.be – Pearl Jam – Ten" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Ultratop.be – Pearl Jam – Ten" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Official Croatian Album Chart website". Top of the Shops. Retrieved April 4, 2009.

- "Top 100 Individual Artist Albums". IRMA. September 24, 2009. Archived from the original on September 19, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- "Italiancharts.com – Pearl Jam – Ten". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Portuguesecharts.com – Pearl Jam – Ten". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Swisscharts.com – Pearl Jam – Ten". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- Top Internet Albums: Ten. Billboard. April 11, 2009. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

- Sprzedaż w okresie 30.06.2014 - 06.07.2014. OLiS. July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- "Year-End top-selling albums across all genres, ranked by sales data as compiled by Nielsen SoundScan". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. 1992. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- "Year-End top-selling albums across all genres, ranked by sales data as compiled by Nielsen SoundScan". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. 1993. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- "Year-End top-selling albums across all genres, ranked by sales data as compiled by Nielsen SoundScan". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. 1994. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- "Year-End top-selling albums across all genres, ranked by sales data as compiled by Nielsen SoundScan". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. 1995. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- "Year-End top-selling albums across all genres, ranked by sales data as compiled by Nielsen SoundScan". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. 1996. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- "Jaaroverzichten 2020". Ultratop. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- Mayfield, Geoff (December 25, 1999). 1999 The Year in Music Totally '90s: Diary of a Decade - The listing of Top Pop Albums of the '90s & Hot 100 Singles of the '90s. Billboard. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- "Pearl Jam Chart History – Hot 100". Billboard. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- "Pearl Jam Chart History – Mainstream Rock Tracks". Billboard. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- "Pearl Jam Chart History – Alternative Songs". Billboard. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- "Pearl Jam in Australian Charts". Australian-charts.com. Hung Medien. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- Pearl Jam - Belgian Singles Chart positions ultratop.be. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

-

Peak positions for Peal Jam's singles in Canadian singles charts:

- RPM charts: "Pearl Jam Top Singles positions". RPM. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- "Chartverfolgung / Pearl Jam / Single". Musicline.de (in German). PhonoNet. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- "Search the charts". Irish Recorded Music Association. Retrieved September 29, 2009. Note: User needs to enter "Pearl Jam" in "Search by Artist" and click "search".

- "Pearl Jam in Dutch Charts". Dutchcharts.nl (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- "Pearl Jam in New Zealand Charts". charts.nz. Hung Medien. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- Pearl Jam - UK Chart Archive officialcharts.com. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- "Gold and Platinum Database Search". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- "Discos de Oro y Platino" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011.

- "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2009 Albums". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020.

- "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – albums 2000". Ultratop. Hung Medien.

- "Brazilian album certifications – Pearl Jam – Ten" (in Portuguese). Pro-Música Brasil.

- "Canadian album certifications – Pearl Jam – Ten". Music Canada.

- "Danish album certifications – Pearl Jam – Ten". IFPI Denmark. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Pearl Jam; 'Ten')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie.

- "Italian album certifications – Pearl Jam – Ten" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Select "Tutti gli anni" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Select "Ten" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Album e Compilation" under "Sezione".

- "New Zealand album certifications – Pearl Jam – Ten". Recorded Music NZ.

- "IFPI Norsk platebransje Trofeer 1993–2011" (in Norwegian). IFPI Norway. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- "Polish album certifications – Pearl Jam – Ten" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry.

- "Guld- och Platinacertifikat − År 1987−1998" (PDF) (in Swedish). IFPI Sweden.

- "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards (Pearl Jam; 'Ten')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien.

- "British album certifications – Pearl Jam – Ten". British Phonographic Industry.

- "American album certifications – Pearl Jam – Ten". Recording Industry Association of America. If necessary, click Advanced, then click Format, then select Album, then click SEARCH.