Teresa Teng

Teng Li-chun (traditional Chinese: 鄧麗君; simplified Chinese: 邓丽君; pinyin: Dèng Lìjūn; Jyutping: Dang6 Lai6-gwan1, 29 January 1953 – 8 May 1995), commonly known as Teresa Teng, was a Taiwanese singer, actress, and musician. Referred as "Asia's eternal queen of pop," Teng became a cultural icon for her contributions to Mandopop, giving birth to the phrase, "Wherever there are Chinese people, there is the music of Teresa Teng".[1]

Teresa Teng | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

鄧麗君 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Born | Teng Li-yun (鄧麗筠) 29 January 1953 Pao-Chung rural town, Yunlin, Taiwan | ||||||||||||

| Died | 8 May 1995 (aged 42) Chiang Mai Rum Hospital, Chiang Mai, Thailand | ||||||||||||

| Burial place | Chin Pao San, New Taipei City, Taiwan 25°15′04″N 121°36′14″E | ||||||||||||

| Nationality | Republic of China (Taiwan) | ||||||||||||

| Occupation | Singer, Actress, TV personality | ||||||||||||

| Years active | 1966–1995 | ||||||||||||

| Awards | Golden Melody Awards – Special Award 1996 (awarded posthumously) | ||||||||||||

| Musical career | |||||||||||||

| Also known as | Teresa Tang Teresa Deng Teng Li-chun Deng Lijun | ||||||||||||

| Genres | C-pop, J-pop, Cantopop | ||||||||||||

| Labels | Universal Music (present) Taiwan: Yeu Jow (1967–71) Haishan (1971) Life (1972–76) Kolin (1977–83) PolyGram (1984–92) Hong Kong: EMI (1971) Life (1971–76) PolyGram (1975–92) Japan: Polydor K.K. (1974–81) Taurus (1983–95) | ||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 鄧麗君 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 邓丽君 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

With a career spanning 30 years, Teng remained widely popular throughout the 1970s and 1980s; she remained popular even up to the first half of the 1990s, up until her death in 1995.[2] Teng was known as a patriotic entertainer whose powerful romantic ballads and performances revolutionized Chinese popular culture during the 1970s and 1980s.[3] She is often credited for bridging the cultural barrier across Chinese-speaking nations, and first artist to connect Japan to much of East and Southeast Asia, by singing Japanese pop songs, many of which were later translated to Mandarin.[4][5][6] She was known for her folk songs and ballads, such as "When Will You Return?" "As Sweet as Honey" and "The Moon Represents My Heart".[7] She recorded songs not only in Mandarin[8] but also in Hokkien,[9] Cantonese,[10] Japanese,[11] Indonesian[12] English[13] and Italian[14] when she was 14 years old. She also spoke French fluently. To date, her songs have been covered by hundreds of singers all over the world.[15]

Teng is widely considered as one of the most successful and influential figures in Asian music and pop culture of all time, considering her deep impact on Asian music scene, particularly the Chinese-speaking world where her influence goes far beyond the music circle, to include the both political and cultural spheres; and where her ability to sing in multiple languages made her an icon in all of Asia that helped birth to the era of region-wide pop superstardom that became today's norm.[16][17][18][19][20][21] According to Billboard, Teng released 25 albums during the last 26 years of her career, selling over 22 million copies worldwide (original sales), with another 50–75 million pirated copies.[22] On May 8, 1995, Teng died from a severe respiratory attack while on vacation in Thailand at the age of 42. She remains a national heroine and a symbol of cultural unity of Taiwan, Hong Kong, mainland China, and Chinese-speaking communities worldwide.[23][24]

Early life

Teng was born in Baozhong Township, Yunlin County, Taiwan on 29 January 1953, to Waishengren parents. Her father was a soldier in the Republic of China Armed Forces from Daming, Hebei, and her mother was from Dongping, Shandong. The only daughter in the family, with three older brothers and a younger brother, she was educated at Ginling Girls High School (私立金陵女中) in Sanchong Township, Taipei County, Taiwan.

As a young child, Teng won awards for her singing at talent competitions. Her first major prize was in 1964 when she sang "Visiting Yingtai" from Shaw Brothers' Huangmei opera movie, The Love Eterne, at an event hosted by Broadcasting Corporation of China. She was soon able to support her family with her singing. Taiwan's rising manufacturing economy in the 1960s made the purchase of records easier for more families. With her father's approval, she quit school to pursue singing professionally.

Career

Teng gained her first taste of fame in 1968 when a performance on a popular Taiwanese music program led to a record contract. She released several albums within the next few years under the Life Records label. In 1973 she attempted to crack the Japanese market by signing with the Polydor Japan label and taking part in the country's Kōhaku Uta Gassen, an annual singing competition of the most successful artists: She was named "Best New Singing Star".[25] Following her success in Japan, Teng recorded several Japanese songs, including original hits such as "Give yourself to the flow of Time" (時の流れに身をまかせ, Toki no Nagare ni Mi wo Makase) which was later covered in Mandarin as "I Only Care About You".

In 1974 the song "Airport" (空港, Kūkō), which was covered in Mandarin as "Lover's Care" (情人的關懷) in 1976, became a hit in Japan. Teng's popularity there continued despite being briefly barred from the country in 1979 for having a fake Indonesian passport she purchased for US$20,000. The subterfuge had seemed necessary due to the official break in relations between Republic of China and Japan that occurred shortly after the People's Republic of China replaced the ROC in the United Nations.

Her popularity boomed in the 1970s after her success in Japan. By now singing in Mandarin, Cantonese, Japanese and English, Teng's influence spread to Malaysia and Indonesia. In Taiwan, she was known not only as the island's most popular export, but as "the soldier's sweetheart" because of her frequent performances for servicemen. Teng was herself the child of a military family. Her concerts for troops featured Taiwanese folk songs that appealed to natives of the island as well as Chinese folk songs that appealed to homesick refugees of the civil war. She gave many free concerts to help the less fortunate or to help raise funds for charities.[26]

In the early 1980s, continuing political tension between China and Taiwan led to her music, along with that of other singers from Taiwan and Hong Kong, being banned for several years in China for being too "bourgeois". Her popularity in China continued to grow nonetheless thanks to its black market. As Teng's songs continued to be played everywhere, from nightclubs to government buildings, the ban on her music was soon lifted. Her fans nicknamed her "Little Deng" because she had the same family name as Deng Xiaoping; there was a saying that "Deng the leader ruled by day, but Deng the singer ruled by night."[27]

Teng's contract with Polydor ended in 1981, and she signed a contract with Taurus Records in 1983 and made a successful comeback appearance in Japan. In 1983, Taurus released her album, Dandan youqing, translated as Light Exquisite Feeling which consisted of settings of 12 poems from the Tang and Song dynasties. The music, written by composers of her earlier hits, blended modern and traditional Oriental and Occidental styles. The most popular single from the album is "Wishing We Last Forever". Teng apparently felt a deep attachment to the mainland, as she immersed herself in the classics of Tang and Song periods.[28] In the television special, she spoke of her desire to contribute in the transmission of "Chinese" culture. Dressed in her period clothing, she commented:

"I have one small wish. I hope everyone will like these songs, so that the flourishing begonias within China's 10 million square kilometres and the treasures of this 5000-year old culture can be handed down generation through song. And through this, I hope our posterity will never forget the happiness, sadness, and glory of being a "Chinese" person."[29]

Gunther Mende, Mary Susan Applegate and Candy de Rouge wrote the song "The Power of Love" for Jennifer Rush. Teng covered it and made it notable in Asian regions. She originally sang it in her Last Concert in Tokyo – eight years before being sung and released by Celine Dion.

Teng performed in Paris during the 1989 Tiananmen student protests on behalf of the students and expressed her support. On 27 May 1989, over 300,000 people attended the concert called "Democratic songs dedicated to China" (民主歌聲獻中華) at the Happy Valley Racecourse in Hong Kong. One of the highlights was her rendition of "My Home Is on the Other Side of the Mountain."[30]

Though Teng performed in many countries around the world, she never performed in mainland China. During her 1980 TTV concert, when asked about such possibility, she responded by stating that the day she performs on the mainland will be the day the Three Principles of the People (三民主義) are implemented there – in reference to either the pursuit of Chinese democracy or reunification under the banner of the ROC."[31][32][33]

Career in Japan

Teresa entered the Japanese market in 1973. On March 1, 1974, Teng released her first Japanese single 'No Matter Tonight or Tomorrow' which marked the beginning of her career in Japan. The single initially received lukewarm market response, and was ranked 75th in the Oricon Chart with the sales approximately 30,000. The Watanabe firm considered giving up using her name. However, considering her success in Asia, the record company decided to release two or three consecutive singles to test the market further. On July 1, 1974, Teng's second single 'Airport' was released. The sales of 'Airport' were huge totalling 700,000 copies. Teresa then released number of successful singles including "Goodbye, my love" which topped Oricon Chart and remained there for weeks. In 1979, she was caught with fake Indonesian passport while entering Japan, and was deported back banning her from entering the country for one year.[34]

After a long absence, Teresa returned to the Japanese market on September 21, 1983 and released her first single 'Tsugunai' (Atonement) after her comeback on 21 January 1984. The single had quite poor response initially, however after a month, sales started to pick up, and after seven months, 'Atonement' eventually ranked 8th in Oricon Chart. By the end of year, sales crossed 700,000 copies and the final sales reached a million copies. Teng won the 'Singer of the year' of Japan Cable Award. 'Tsugunai' won the most popular song category, and stayed in Oricon Chart for as long as a year. The success broke the sales record of all her previous period (1974–1979). On February 21, 1985, her another single 'Aijin' (Lover) topped the Oricon Chart this time in the first week of its release. It remained #1 for fourteen consecutive weeks and sales breaking 1.5 million mark. In the same year, Teresa won 'Singer of the year' for second time. Moreover, she was invited to perform in Kouhaku Uta Gassen, which represents the highest honour in the Japanese music world. After this, her next single Toki no Nagare ni Mi o Makase was released on 21 February 1986. The single topped Oricon Chart and sales of the single reached 2.5 million and became the most popular single in Japan the same year. She won 'Singer of the year' of Japan Cable Award for third time in a row, and performed in Kouhaku Uta Gassen again. In June, 1987, Teng released her next single 'Wakare no yokan', which was another huge success with sales reaching 1.5 million to win another 'Singer of the year' of Japan Cable Award. To this day, Teng remains only singer to win this award for four consecutive years (1984–1987) in the history of Japanese music.[35]

Death and commemorations

Teng died from a severe asthma attack,[36] though doctors and her partner Paul Quilery had speculated that she died from a heart attack due to a side effect of an overdose of unspecified amphetamines while on holiday in Chiang Mai, Thailand at the age of 42 on 8 May 1995.[37] Quilery was buying groceries when the attack occurred.[37] He was aware that Teng relied on the same medication in the two months before her death with minor attacks.[37] Teng had asthma throughout her adult life.

.jpg.webp)

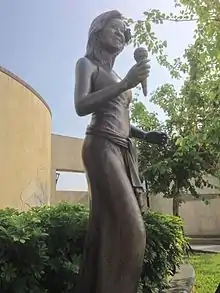

Teng's death produced unified sense of loss throughout all of Asia.[38] Her funeral in Taiwan became the largest scale state-sponsored funeral in country's history, second to only ROC leader Chiang Kai-shek. Roughly 30,000 mourners attended the ceremony, and another 30,000 lined the thirty-mile route to the sprawling mountain ceremony where she would be enterred.[39] Her funeral were broadcast to television stations across many Asian countries.[40] Teng was given state honors at her funeral with Taiwan's flag draped around her coffin. Hundreds of high-ranking officials and dignitaries, including commanders from three branches of the military attended the funeral who carried her coffin to her grave. A day of national mourning were declared and president Lee Teng-hui was among the thousands in attendance.[41] Teng was posthumously awarded the Ministry of Defense's highest honor for civilians, the KMT's "Hua-hsia Grade One Medal", the Overseas Chinese Affairs' Commission's "Hua Guang Grade one Medal," and the president's commendation.[42] She was buried in a mountainside tomb at Chin Pao San, a cemetery in Jinshan, New Taipei City (then Taipei County) overlooking the north coast of Taiwan. The grave site features a statue of Teng made of gold and a large electronic piano keyboard set in the ground that can be played by visitors who step on the keys. The memorial is often visited by her fans.[43]

In May 1995, Shanghai Radio host Dalù dedicated the Sunday morning broadcast to the Taiwanese singer, who passed away a few days earlier. Spreading her songs was banned in China and the journalist was formally warned for this act.[44]

In 1995, a tribute album called A Tribute to Teresa Teng was released, which contained covers of Teng's songs by prominent Chinese rock bands.

In May 2002, a wax figure of Teng was unveiled at Madame Tussauds Hong Kong.[45] A house she bought in 1986 in Hong Kong at No. 18 Carmel Street, Stanley also became a popular fan site soon after her death. Plans to sell the home to finance a museum in Shanghai were made known in 2002,[46] and it subsequently sold for HK$32 million. It closed on what would have been her 51st birthday on 29 January 2004.[47]

To commemorate the 10th anniversary of her death, the Teresa Teng Culture and Education Foundation launched a campaign entitled "Feel Teresa Teng". In addition to organizing an anniversary concert in Hong Kong and Taiwan, fans paid homage at her shrine at Chin Pao San Cemetery. Additionally, some of her dresses, jewelry and personal items were placed on exhibition at Yuzi Paradise, an art park outside Guilin, China.[48] The foundation also served as her wishes to set up a school or educational institute.[37]

In April 2015, a set of four stamps featuring Teng were released by the Chunghwa Post.[49]

Personal life

In 1978, Teng met Beau Kuok, a Malaysian businessman and son of multi-billionaire Robert Kuok. They were engaged in 1982, but Teng called off the engagement due to prenuptial agreements which stipulated that she had to quit and sever all ties with the entertainment industry, as well as fully disclose her biography and all her past relationships in writing.[50]

Teng had a high-profile relationship with Jackie Chan while she was traveling in Los Angeles, but due to their personality differences, they parted ways.

In 1998, Paul Quilery revealed that Teng was engaged to him, and was due to get married in August 1995.[37]

Discography

Awards

Teng received the following awards in Japan:[51]

- The New Singer Award for "Kūkō" (空港) in 1974.

- The Gold Award in 1986 for "Toki no Nagare ni Mi o Makase" (時の流れに身をまかせ).

- The Grand Prix for "Tsugunai" (つぐない) in 1984: "Aijin" (愛人) in 1985; and "Toki no Nagare ni Mi o Makase" in 1986. This was the first time anyone had won the Grand Prix three years in a row.

- The Outstanding Star Award for "Wakare no Yokan" (別れの予感) in 1987.

- The Cable Radio Music Award for "Wakare no Yokan" in 1987 and 1988.

- The Cable Radio Special Merit Award (有線功労賞) in 1995 for three consecutive Grand Prix wins.

Legacy

Cultural Influence

Widely accepted as Asia's singing queen,[52] Teng's fame and success had a huge cultural impact in Asia. As for many, Teng is recognized as a Far East's first International singing star [53] whose popularity and music recordings of '70s and '80s had a lasting effect on Asian diaspora and elsewhere.[28] Until the late 1970s for 3 decades, foreign music and art were not allowed into China, and love songs were virtually unknown. By incorporating traditional Chinese folk with western music influences she created her own music style that greatly influenced further music creations.[6][54] Her songs were more about love, personal emotions for one's hometown, and sometime social issues in society, a striking contrast to the then state-sponsored propaganda songs in China – often revolutionary songs praising the ruling party, lacking in wide range of human emotions and modes of expression. At the time, personal relationship were often deemed too "unimportant" to be openly discussed.[55][56] In 1977, Teng's popular romantic song "The Moon Represents My Heart," released that became one of the first foreign songs to break into the country. Teng's songs over the following decade further revolutionized Chinese music scene and culture that marked the end of extremely tight control exercised in preceding 3 decades by communist party over Chinese society and culture.[57][3]

Ching-Cheng Chen, a professor at The University of Edinburgh interviews Wu'erkaixi in 2010, one of the leaders of the democracy movement in 1989, and now living under political refuge in Taiwan. He indicated that the students who listened to Deng Lijun's songs in the 1980s actually discovered the desire for pursuit of freedom through her singing voice. Therefore, when Deng Lijun passed away in 1995, they felt sad not only for the loss of a singer, but felt regret for the disappearance of an era of ideals. What made them feel truly sad was their desire for a better living space and political freedom brought by Deng Lijun's singing voice had now completely vanished with her death. Not only was her death, an end of pursuit for an 'ideal era', it was also the termination of a rebellious attitude.

He further adds:[58]

"To Chinese people, Deng Lijun was a great person. If Deng Xiao-ping brought economic freedom to China, Deng Lijun brought liberation of [the] body and [free] thinking to China. We can now see the rise of China. However, Chinese people do not enjoy more freedom. Until now, we've really understood that the liberation of body and spirit is more important than economic freedom."

Teng enjoyed widespread popularity in Japan and Southeast Asia throughout her career, achieving a "cult status" in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Mainland China, and Japan, where she became a "barometer of cross-strait relations," in rising geopolitical tensions at the time,[59] and one of the first artist to truly break through international barrier paving the way for many Asian musicians further and opening the door for artists in Asia to international success that were previously confined to national boundary.[6][21][16] Her songs have been covered by several hundreds of singers all over the world; among them few notable ones are Faye Wong, Andy Lau, Leslie Cheung, Jon Bon Jovi, Siti Nurhaliza, Shila Amzah, Katherine Jenkins, Im Yoon-ah, David Archuleta, University of Utah Singers, Korean girl group f(x) (group), English vocal group Libera (choir), Jewish singer Noa (singer), Grammy award-winning American musician Kenny G, legendary Kiwi pianist Carl Doy, Cuba's leading a cappella musical band Vocal Sampling, and among others. Her songs are also featured in various International films, such as Rush Hour 2, The Game, Prison On Fire, Year of the Dragon, Formosa Betrayed, Gomorrah, and Crazy Rich Asians. In 1980, Teng became the first singer of Chinese ethnicity to perform at the Lincoln Centre in New York City in the United States, one of the most famous musical venues in US.[60]

The 1996 Hong Kong film Comrades: Almost a Love Story, directed by Peter Chan, features the tragedy and legacy of Teng in a subplot to the main story. The movie won best picture in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and at the Seattle Film Festival in the United States. In 2007, TV Asahi produced a TV movie entitled Teresa Teng Monogatari (テレサ・テン物語)[61] to commemorate the 13th anniversary of her death. Actress Yoshino Kimura starred as Teng.

To the Chinese who grew up with her music, Teng was far more than just a pop singer. She became a symbol of unity between Mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong in 70s and 80s, when politics were pushing the three of them apart. Her sentimental love songs arouse the feeling of romance and personal freedom, transcended ideological barriers, and bridged relationship between states. In Taiwan, she remains a highly revered figure where she is regarded as a national heroine due to her dedication to music for everyone.[40][62][63][64]

Peter Chan, a Hong Kong filmmaker states in his interview with Michael Berry, a professor of Chinese cultural studies at University of California, Los Angeles:[65]

"Teresa Teng... is such an icon for all three China's i.e Hong Kong, Taiwan and the mainland. She is really the one who pulled everyone together. If you were from China in 1985, there was nobody else but Teresa Teng. She also herself represent that through her own diasporic background. She herself is the incarnation of the rootless Chinese."

.jpg.webp)

In 1974, Teng entered the Japanese market, two years after Japan severed diplomatic ties with Taiwan. She was extremely popular in Japan throughout the 1970's and 1980's, having lived off her royalties in the country after semi-retiring in the late '80s. During this tenure, Teng recorded and performed Japanese pop songs, often termed as Kayokyoku by Japanese media, and helped connect Japan to much of Far East, particularly Taiwan, China, and some of Southeast Asia, helping bridge the gap between them, many of which were later translated in Mandarin, as reported by Nippon.com[66] and Billboard.[67]

Hirano Kumiko, an author at Nippon.com writes:[66]

"For Japanese, Teresa Teng was more than just a popular singer. By performing kayōkyoku, she connected Japan to its Asian neighbors. She taught us about the profundity of Chinese culture, whether in her birthplace of Taiwan, her ancestral home of China, or Hong Kong, which she loved throughout her life. We, her Japanese fans, will never forget her velvety voice and the brief, beautiful radiance of her life."

Considered a "brilliant linguist" by New York Times,[68] Teng has been named one of the world's seven greatest female singers by Time magazine in 1986.[69] In 2009, to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the People's Republic of China, a government web portal conducted an online poll to choose "The Most Influential Cultural icon in China since 1949". Over 24 million people voted and Teng came out as a winner with 8.5 million votes. In 2010, CNN included her among the 20 biggest music icons of the past 50 years alongside Michael Jackson, Elvis Presley and The Beatles.

In 2013, Teng was "revived" briefly in a Jay Chou concert where she appeared as a 3D virtual hologram and sang three songs with Chou. She was later resurrected in a Japanese TV show using 3D VR technology in 2017.[70]

On 29 January 2018, a Google Doodle was released across Japan, China, Taiwan, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, India, Philippines, Australia, New Zealand, Finland, Sweden, Bulgaria, Canada and Iceland to honor the singer's 65th birth anniversary.[71][72]

Reactions

Teng's housekeeper and close friend Cheong kam-mei, who spent five years with Teng, as her housekeeper and cook. She shared the singer's joys and sadness recalls her lost friend:

"She never treated me as her employee but as her family. She was a great boss and treated us with no bias and never looked down on us. Yet she did have her own pressure and sadness. She would chat with me and cry before me when she was sad. Whenever I saw her crying, I cried with her. " – Teng's former employee[73]

In 1984, Teresa held "A Billion Applause Concert" where she was interviewed by numerous foreign reporters, one of them being New York Times. In an interview, when asked about her musical influences and its journey, Teng replied, "When I was very young, I was highly influenced by Chinese songs and music," Miss Teng said, who prefaces some of her songs by reciting snatches of ancient Chinese poetry. I was raised on Chinese folk songs sung to me by my mother in my early years while growing up", Teng said to the reporter. [74]

References

- Mok, Laramie (6 May 2020). "5 of Teresa Teng's songs, each in a different language – 25 years after the legendary Taiwanese singer died from an asthma attack". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Taiwan (1 September 2015). "Icon for the Ages". Taiwan Today. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- 王曉寒 (2006). 征服英語新聞. 臺灣商務印書館. ISBN 978-957-05-2098-9.

- "Google Doodle Celebrates Singing Sensation Teresa Teng". Time. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Teresa Teng: An Asian Idol Loved in Japan". nippon.com. 19 February 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Cheng, Chen-Ching (24 November 2016). "Negotiating Deng Lijun: collective memories of popular music in Asia during the Cold War period". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Wudunn, Sheryl. "Teresa Teng, Singer, 40, Dies; Famed in Asia for Edm Songs Archived 18 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine." The New York Times. 10 May 1995. Listed as one of Top Timeless Classic Chinese Song Ever Archived 8 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- "Ji Duo Chou - Teresa Teng - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "邓丽君 - 走马灯 (Teresa Teng - Zao Be Tin) - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Teresa Teng 鄧麗君 - Mong Gei Ta 忘記他 - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "Teresa Teng - Toki No Nagare Ni Mi Wo Makase - 時の流れに身をま - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- "Biarlah Sendiri Teresa Teng / 鄧麗君 - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "邓丽君:I've never been to me - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "鄧麗君 Teresa Teng 手提箱女郎 (意大利語) Lady With A Suitcase (Italian) - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- hermesauto (20 August 2015). "Bon Jovi covers Teresa Teng classic – in Mandarin". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Hsu, Hua. "The Melancholy Pop Idol Who Haunts China". The New Yorker. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- "Teresa Teng Essentials". Apple Music. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- "Teresa Teng is Asia's Most Beloved Singer, Her Timeless Voice Still Melts Hearts". visiontimes.com. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- "Teresa Teng Tickets". StubHub India. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- "Digital Domain Holds Asia's First Virtual Concert of the Legendary Taiwanese Pop Diva Teresa Teng". www.acnnewswire.com. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- "Obituary: Teresa Teng". The Independent. 22 May 1995. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Inc, Nielsen Business Media (20 May 1995). Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc.

- "Prodigy of Taiwan, Diva of Asia: Teresa Teng". Association for Asian Studies. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- "TAIWAN: PEOPLE PAY LAST RESPECTS TO SINGER TERESA TENG | AP Archive". www.aparchive.com. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Teresa Teng: An Asian Idol Loved in Japan". Nippon Communications Foundation. 19 February 2016. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "Concerts to pay tribute to Teresa Teng". The Star. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Zhou, Kate Xiao (2011). China's Long March to Freedom: Grassroots Modernization. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-4128-1029-6. LCCN 2009007967. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Teresa Teng's songs still resonate 20 years on". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Lee, Lorin Ann (May 2012). Singing Sinophone : a case study of Teresa Teng, Leehom Wang, and Jay Chou (thesis thesis).

- 1989年邓丽君力排众议为六四献唱 (Video file) (published 13 September 2007). 27 May 1989. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2019 – via YouTube.

- 鄧麗君國父紀念館演唱會 1980年10月4日 (Video file) (published 13 January 2016). 4 October 1980. Retrieved 29 May 2020 – via YouTube.

- "PHOTO ESSAYS Teresa Teng's heavenly voice continues to echo transcendently". Central News Agency (Taiwan). 5 July 2015. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "鄧麗君逝世20週年 追憶天使美聲". www.cna.com.tw. Central News Agency (Taiwan). Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Cheng, Chen-Ching (2016). Negotiating Deng Lijun: Collective Memories of Popular Music in Asia During the Cold War Period. University of Edinburgh. pp. 204–214.

- Cheng, Chen-Ching (2016). Negotiating Deng Lijun: Collective Memories of Popular Music in Asia During the Cold War Period. University of Edinburgh. pp. 216–218.

- WuDUNN, SHERYL (10 May 1995). "Teresa Teng, Singer, 40, Dies; Famed in Asia for Love Songs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Teresa Teng those years before she passing away 鄧麗君 邓丽君 最後的秘密生活2 on YouTube

- Inc, Nielsen Business Media (20 May 1995). Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc.

- "Prodigy of Taiwan, Diva of Asia: Teresa Teng". Association for Asian Studies. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- Inc, Nielsen Business Media (20 May 1995). Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc.

- "Taiwan bids farewell to Teresa Teng". United Press International. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Lee, Lily Xiao Hong (8 July 2016). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: v. 2: Twentieth Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-49923-9.

- Teresa Teng's grave. North Coast & Guanyinshang official website. Retrieved 2 January 2007. Archived 30 August 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- "Interview: Chinese journalist Dalù and his escape to Italy". www.italianinsider.it. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Taiwanese diva's home 'for sale' Archived 29 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News, 29 July 2002. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- "A Retrospective Look at 2004". Archived from the original on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2008.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). HKVP Radio, Dec 2004. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- "Teresa Teng in loving memory forever". China Daily. 8 May 2005. Archived from the original on 9 April 2007. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

- Huang, Lee-hsiang (16 April 2015). "Teresa Teng featured in new stamp set". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- "Kuok Khoon Chen". World encyclopedic knowledge.

- " テレサ・テン データべース (Teresa Teng Database)" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- "Memories of Teresa Teng - How she accrued 1 billion fans!". NTD. 27 July 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- "Obituary: Teresa Teng". The Independent. 22 May 1995. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- China (Taiwan), Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of (1 March 1982). "Teresa Teng: Asian Star". Taiwan Today. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Baranovitch, Nimrod (1 August 2003). China's New Voices: Popular Music, Ethnicity, Gender, and Politics, 1978-1997. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-93653-9.

- "The way we were during past 30 years". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Baranovitch, Nimrod (1 August 2003). China's New Voices: Popular Music, Ethnicity, Gender, and Politics, 1978–1997. University of California Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-520-93653-9.

- Cheng, Chen-Ching (2016). Negotiating Deng Lijun: Collective Memories of Popular Music in Asia During the Cold War Period. University of Edinburgh. p. 317.

- "Banned by Beijing, Teresa Teng's music was loved across China". South China Morning Post. 10 May 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- News, Taiwan. "Late singer Teresa Teng's exhibition to be he..." Taiwan News. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- "テレビ朝日|スペシャルドラマ テレサ・テン物語". Archived from the original on 2 March 2010.

- "Taiwan: People Pay Last Respects To Singer Teresa Teng". AP Archive. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- "Teresa Teng: An Asian Idol Loved in Japan". nippon.com. 19 February 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- "Singing Sensation Teresa Teng Would Have Turned 65 Today. Here's What You Should Know About Her". Yahoo. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- Chow, Rey; Chow, Anne Firor Scott Prof of Literature in Trinity Clg of Arts/Sciences Rey (2007). Sentimental Fabulations, Contemporary Chinese Films: Attachment in the Age of Global Visibility. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13333-3.

- "Teresa Teng: An Asian Idol Loved in Japan". nippon.com. 19 February 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- Inc, Nielsen Business Media (20 May 1995). Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc.

- Wudunn, Sheryl (10 May 1995). "Teresa Teng, Singer, 40, Dies; Famed in Asia for Love Songs (Published 1995)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Limited, Bangkok Post Public Company. "Teresa Teng 'lives again'". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Teresa Teng "RESURRECTED" on Japanese TV Show, retrieved 5 May 2020

- "Teresa Teng's 65th Birthday – Global Events". Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Karki, Tripti (29 January 2018). "Google Doodle celebrates 65th birth anniversary of Taiwanese singer Teresa Teng". www.indiatvnews.com. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- "Remembering Teresa Teng". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Wren, Christopher S. (30 January 1984). "MUSIC TO MAINLAND EARS, OFF-KEY TO PEKING CHIEFS (Published 1984)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Teresa Teng. |

- Teresa Teng Foundation 鄧麗君文教基金會

- Teresa Teng at AllMusic

- Teresa Teng discography at MusicBrainz

- Teresa Teng at IMDb