Territorial Force

The Territorial Force was a part-time volunteer component of the British Army, created in 1908 to augment British land forces without resorting to conscription. The new organisation consolidated the 19th-century Volunteer Force and yeomanry into a unified auxiliary, commanded by the War Office and administered by local County Territorial Associations. The Territorial Force was designed to reinforce the regular army in expeditionary operations abroad, but because of political opposition it was assigned to home defence. Members were liable for service anywhere in the UK and could not be compelled to serve overseas. In the first two months of the First World War, territorials volunteered for foreign service in significant numbers, allowing territorial units to be deployed abroad. They saw their first action on the Western Front during the initial German offensive of 1914, and the force filled the gap between the near destruction of the regular army that year and the arrival of the New Army in 1915. Territorial units were deployed to Gallipoli in 1915 and, following the failure of that campaign, provided the bulk of the British contribution to allied forces in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. By the war's end, the Territorial Force had fielded twenty-three infantry divisions and two mounted divisions on foreign soil. It was demobilised after the war and reconstituted in 1921 as the Territorial Army.

| Territorial Force | |

|---|---|

Presentation of colours and guidons to 108 units of the Territorial Force by King Edward VII at Windsor Palace, 19 June 1909 | |

| Active | 1908–1921 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Type | Volunteer auxiliary |

| Engagements | Home defence, Western Front, Gallipoli Campaign, Sinai and Palestine Campaign, Italian Front, Mesopotamian Campaign |

The force experienced problems throughout its existence. On establishment, fewer than 40 per cent of the men in the previous auxiliary institutions transferred into it, and it was consistently under strength until the outbreak of the First World War. It was not considered to be an effective military force by the regular army and was denigrated by the proponents of conscription. Lord Kitchener chose to concentrate the Territorial Force on home defence and raise the New Army to reinforce the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France, a decision which disappointed the territorials. The need to replace heavy losses suffered by the BEF before the New Army was ready forced Kitchener to deploy territorial units overseas, compromising the force's ability to defend the homeland. To replace foreign-service units, the Territorial Force was doubled in size by creating a second line which mirrored the organisation of the original, first-line units. Second-line units assumed responsibility for home defence and provided replacement drafts to the first line. The second line competed with the New Army for limited resources and was poorly equipped and armed. The provision of replacements to the first line compromised the second line's home defence capabilities until a third line was raised to take over responsibility for territorial recruitment and training. The second line's duties were further complicated by the expectation, later confirmed, that it too would be deployed overseas.

Territorial units were initially deployed overseas to free up regular units from non-combat duties. On the Western Front, individual battalions were attached to regular army formations and sent into action, and the territorials were credited with playing a key role in stopping the German offensive. The first complete territorial division to be deployed to a combat zone arrived in France in March 1915. Territorial divisions began participating in offensive operations on the Western Front from June 1915 and at Gallipoli later that year. Because of the way it was constituted and recruited, the Territorial Force possessed an identity that was distinct from the regular army and the New Army. This became increasingly diluted as heavy casualties were replaced with conscripted recruits following the introduction of compulsory service in early 1916. The Territorial Force was further eroded as a separate institution when County Territorial Associations were relieved of most of their administrative responsibilities. By the war's end, there was little to distinguish between regular, territorial and New Army formations.

Background

The British Army of the late 19th century was a small, professional organisation designed to garrison the empire and maintain order at home, with no capacity to provide an expeditionary force in a major war.[1] It was augmented in its home duties by three part-time volunteer institutions, the militia, the Volunteer Force and the yeomanry. Battalions of the militia and Volunteer Force had been linked with regular army regiments since 1872, and the militia was often used as a source of recruitment into the regular army. The terms of service for all three auxiliaries made service overseas voluntary.[2][3] The Second Boer War exposed weaknesses in the ability of the regular army to counter guerrilla warfare which required additional manpower to overcome. The only reinforcements available were the auxiliaries – nearly 46,000 militiamen served in South Africa and another 74,000 were enlisted into the regular army; some 20,000 men of the Volunteer Force volunteered for active service in South Africa; and the yeomanry provided the nucleus of the separate Imperial Yeomanry for which over 34,000 volunteered.[4][5]

The war placed a significant strain on the regular forces. Against a background of invasion scares in the press, George Wyndham, Under-Secretary of State for War, conceded in Parliament in February 1900 that instead of augmenting the regular army's defence of the British coast, the auxiliary forces were the main defence.[6][7][lower-alpha 1] The questionable performance of the volunteers, caused by poor standards of efficiency and training, led to doubts in both government and the regular army about the auxiliary's ability to meet such a challenge.[8][9] The war also exposed the difficulty in relying on auxiliary forces which were not liable for service overseas as a source of reinforcements for the regular army in times of crisis. In 1903, the Director of General Mobilisation and Military Intelligence reported an excess of home defence forces which could not be relied upon to expand the army in foreign campaigns.[10] The utility of such forces was brought further into question by British military planning; the Royal Navy formed the primary defence against invasion, and studies in 1903 and 1908 concluded that the threat of invasion was negligible, despite popular perceptions to the contrary.[11]

Reform efforts

The first reform efforts were undertaken in 1901 by William St John Brodrick, Secretary of State for War. They were designed to improve the training of the auxiliary forces and transform the yeomanry from cavalry to mounted infantry.[12] Brodrick's efforts were met with opposition from auxiliary interests in the government, and the yeomanry in particular proved resistant to change. A royal commission on auxiliary forces concluded in 1904 that the volunteer organisations were not fit to defend the country unaided and that the only effective solution would be to introduce conscription.[13][lower-alpha 2] This option, regarded as political suicide by all parties, was immediately rejected. Brodrick's successor, H. O. Arnold-Forster, also failed to overcome opposition to his reform efforts.[16][17][18] In December 1905, a Liberal government took office, bringing in Richard Haldane as the Secretary of State for War. His vision was for a nation that could be mobilised for war without resorting to conscription – a "real national army, formed by the people".[19] His solution was the Territorial Force, financed, trained and commanded centrally by the War Office and raised, supplied and administered by local County Territorial Associations.[20]

Haldane was able to overcome opposition and pass the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act 1907 which created the force, though not without compromise. His plan to give civic, business and trade union leaders a major role in running the County Territorial Associations was significantly reduced in the face of opposition to civilian encroachment in military affairs. Instead, the associations were chaired by Lord Lieutenants and run by traditional county military elites.[21][22][23] Militia representatives refused to accept Haldane's plans to allocate a proportion of the militia as a reserve for the regular army and incorporate the remainder into the Territorial Force. After three attempts to persuade them, Haldane abolished the militia and created the Special Reserve.[24]

Crucially, Haldane's efforts were based on the premise that home defence rested with the navy and that the imperative for army reform was to provide an expeditionary capability.[25] His reorganisation of the regular army created a six-division Expeditionary Force, and his plan was for the Territorial Force to reinforce it after six months of training following mobilisation. Representatives of the existing auxiliary forces and elements within the Liberal party opposed any foreign service obligation. To ensure their support, Haldane declared the Territorial Force's purpose to be home defence when he introduced his reforms in Parliament, despite having stressed an overseas role eight days previously. The last-minute change caused significant difficulties for the force throughout its existence.[26][27]

Formation

The Territorial Force was established on 1 April 1908 by the amalgamation of the Volunteer Force and the yeomanry.[lower-alpha 3] The Volunteer Force battalions became the infantry component of the Territorial Force and were more closely integrated into regular army regimental establishments they had previously been linked to; for example, the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Volunteer Battalions of the regular army's Gloucestershire Regiment became the regiment's 4th, 5th and 6th Battalions (Territorial Force).[28][29][30] The infantry was organised into 14 territorial divisions, each of three brigades. The yeomanry regiments became the mounted component of the Territorial Force, organised into 14 mounted brigades. Brigades and divisions were equipped with integral supporting arms along regular army lines, comprising territorial units of artillery (totalling 182 horse and field batteries), engineers and signals, along with supply, medical and veterinary services. Each territorial unit was assigned a specific role either in coastal defence, supplementing 81 territorial companies of the Royal Garrison Artillery manning fixed defences, or as part of the mobile Central Force.[31][29] Training was managed by a permanent staff of regular army personnel attached to territorial units.[32]

Recruits to the Territorial Force had to be aged between 17 and 35. They enlisted for a four-year term which could be extended by an obligatory year in times of crisis. Members could terminate their enlistment on three months' notice and payment of a fine. Recruits were required to attend a minimum of 40 drill periods in their first year and 20 per year thereafter. All members were required to attend between eight and fifteen days of annual camp.[33] The force was liable to serve anywhere in the UK. Members were not required to serve overseas but could volunteer to do so. Haldane, who still regarded the force's primary function to be the expansion of the Expeditionary Force, hoped that up to a quarter of all territorials would volunteer on mobilisation. The Imperial Service Obligation was introduced in 1910 to allow territorials to volunteer in advance.[26][34] It was illegal to amalgamate or disband territorial units or transfer members between them.[35]

Reception

The reforms were not received well by the auxiliaries. The exclusion of the militia rendered Haldane's target of just over 314,000 officers and men for the Territorial Force unattainable. The new terms of service imposed an increased commitment on members compared to that demanded by the previous auxiliary institutions. By 1 June 1908, the force had attracted less than 145,000 recruits. Despite considerable efforts to promote the new organisation to the former auxiliary institutions, less than 40 per cent of all existing auxiliaries transferred into it.[36]

The County Territorial Associations emphasised pride in a local territorial identity in their efforts to recruit new members, and used imagery of local scenes under attack to encourage enlistment.[37] In general, the force attracted recruits from the working class, though they were mainly artisans rather than the unskilled labourers who filled the ranks of the regular army. In some units, middle and working classes served together. Units which recruited from the more affluent urban centres contained a significant proportion of well-educated white-collar workers. Territorial officers were predominantly middle class, meaning that in some units there was little to separate officers from other ranks in terms of social status.[38][lower-alpha 4]

Territorial officers were regarded as social inferiors by the regular army's more privileged officer corps. The territorials' relatively narrow social spectrum resulted in a less formal system of self-discipline than the rigid, hierarchical discipline of the regular army, feeding a professional prejudice against the amateur auxiliary.[40] The regular army had no more faith in the territorials' abilities than it had in those of the force's predecessors. Territorial standards of training and musketry were suspect, and the reputation of the territorial artillery was so poor that there were calls for it to be disbanded. Regular officers, fearing for their career prospects, often resisted postings as territorial adjutants.[41][42] The Army Council predicted that, even after six months of intensive training on mobilisation, the force would not reach a standard at which two territorial divisions could be considered the equal of one regular division as planned.[43] In 1908 and 1914, it was decided that two of the army's six expeditionary divisions should be retained in the UK for home defence, so ineffective was the Territorial Force perceived to be in the role to which it had been assigned.[41]

Conscription debate and pre-war problems

In 1910, Lord Esher, pro-conscription chairman of the London County Territorial Association, wrote in the National Review that the country would have to choose between an under-strength voluntary auxiliary and compulsory service.[44] In his opinion, the Territorial Force was the last chance for the volunteer tradition, and its failure would pave the way for conscription.[45] Advocacy for compulsory service was led by the National Service League (NSL), which regarded reliance on a naval defence against invasion as complacent and a strong home army as essential.[46] A bill sponsored by the NSL in 1909 proposed using the Territorial Force as the framework for a conscripted home army. When that failed, the league became increasingly antagonistic towards the auxiliary.[47] The force was denigrated for its excessive youth, inefficiency and consistently low numbers, and ridiculed in the popular press as the "Territorial Farce".[48][49] The NSL's president – the former Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, Lord Roberts – enlisted the support of serving officers in a campaign against it, and in 1913 the Army Council declared its support for conscription.[50][51] Even prominent members of the force itself favoured compulsory service, and by April 1913 ten County Territorial Associations had expressed support for it.[52][47]

The relationship between the County Territorial Associations and the War Office was often acrimonious. The associations frequently complained about excessive bureaucracy and inadequate finance. The military authorities begrudged the money that could have been spent on the regular army being wasted on what they perceived as an inefficient, amateur auxiliary.[53] Efforts to provide adequate facilities, for example, were undermined by slow responses from the War Office which, when finally forthcoming, often rejected the associations' plans outright or refused to allocate the full financing requested. In 1909, the Gloucestershire association complained that "most of our association are businessmen and are unable to understand why it takes ten weeks and upwards to reply" after waiting for a response to its proposed purchase of a site for a field ambulance unit.[54] Somerset lost three sites for a proposed new drill hall because the War Office took so long to approve plans, and Essex had to wait five years before it received approval for the construction of new rifle ranges.[55] Good facilities were regarded by the associations as important for efficiency, unit esprit de corps and recruitment, and the authorities' parsimony and apparent obstruction were seen as undermining these.[56]

The force failed to retain large numbers of men after their initial enlistment expired, and it consistently fell short of its established strength. It reached a peak of 268,000 men in 1909 when invasion scares prompted a surge in recruitment, but by 1913 numbers had declined to less than 246,000, and the officer corps was nearly 20 per cent under-subscribed.[57][58][59] In 1910, a third of the force had not completed the minimum level of musketry training. Only 155,000 territorials completed the full 15-day annual camp in 1912, and around 6,000 did not attend at all. In 1909, some 37 per cent of the rank and file were under 20 years old; in the opinion of the Inspector-General of the Home Forces, this proportion rendered the force too immature to be effective. In 1913, approximately 40,000 territorials were under 19 years old, the minimum age at which they could volunteer for service overseas. Barely seven per cent of the force had accepted the Imperial Service Obligation, seriously compromising its viability as a reinforcement for the Expeditionary Force.[60][61] Because the military authorities regarded the Territorial Force as weak and saw no value in an auxiliary that was not liable for foreign service, they prioritised expenditure on the regular army, leaving the force armed with obsolete weapons.[41]

First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War, Lord Kitchener by-passed the Territorial Force and, with the approval of the military authorities, raised instead the New Army of volunteers to expand the regular army. His decision was based not only on professional prejudice – he regarded the territorials as a joke, led by "middle-aged professional men who were allowed to put on uniform and play at soldiers"[62] – but also on an appreciation of the constraints imposed by the force's constitution. He feared that the County Territorial Associations would be unable to cope with the task of recruiting and training large numbers. He also believed that because so few territorials had thus far volunteered for foreign service, the Territorial Force was better suited for home defence than as a means of expanding the army overseas.[63][64]

Mobilisation and training

At the end of July, territorial Special Service Sections began patrolling the east coast. On the day before the declaration of war, the 1st London Brigade was dispersed by platoons to protect the rail network between London and Southampton.[65] The remainder of the Territorial Force was mobilised on the evening of 4 August 1914, and war stations were quickly occupied by those units with bases located nearby. By 6 August, for example, units of the Wessex Division were concentrated at Plymouth while those of the Northumbrian Division took up positions in the east coast defences, and the following day elements of the Welsh Division were gathered in the area of Pembroke Dock.[66] Some formations assembled close to their bases before moving on to their war stations; the Highland Division, for example, gathered at various locations north of Edinburgh before proceeding to Bedford, north of London. Defence duties resulted in some divisions being dispersed; a brigade of the West Riding Division, for example, was deployed to watch the east coast while the rest of the division guarded railways and munitions factories inland, and the brigades of the East Anglian Division were widely scattered about East Anglia.[67]

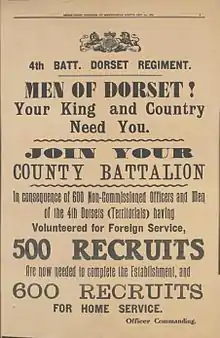

On 13 August 1914, Kitchener signalled a willingness to deploy overseas those territorial units in which 80 per cent of the men (reduced to 60 per cent at the end of the month) had accepted the Imperial Service Obligation.[68] Despite the low uptake before the war, 72 per cent of the rank and file volunteered for foreign service by the end of September.[69] The first full territorial divisions to be deployed overseas were used to free up imperial garrisons. The East Lancashire Division was sent to Egypt in September, and three territorial divisions had been deployed to India by January 1915.[70][lower-alpha 5] Territorial battalions released regular troops stationed at Aden, Cyprus, Gibraltar and Malta. Five regular army divisions were created from the troops released by the territorials' deployments.[72] The extent to which territorials accepted the obligation varied considerably between battalions; some registered 90 per cent or more acceptance, others less than 50 per cent. The difficulties were not restricted to the rank and file, and many battalions sailed for foreign service with officers who had been newly promoted or recruited to replace those who had chosen to remain at home.[73]

The territorials faced difficulties as they trained up to operational standard. Some artillery units did not get an opportunity to practise with live ammunition until January 1915. Rifle practice suffered due to lack of rifles, practice ammunition and ranges on which to use them. Because there was insufficient transport, a motley collection of carts, private vehicles and lorries were pressed into service. The animals used to pull the non-motorised transport or mount the yeomanry ranged in pedigree from half-blind pit ponies to show horses.[74][lower-alpha 6] The Territorial Force competed with the New Army for recruits, and the War Office prioritised the latter for training and equipment.[77] Many of the regular army staff posted to territorial units were recalled to their parent regiments, and those professionals that still remained were transferred to territorial reserve units in January 1915. Training proved difficult for formations that were widely dispersed as part of their defence duties, and was complicated for all by the need to reorganise the territorial battalions' outdated eight-company structure to the army's standard four-company battalion.[78]

Second line

On 15 August, County Territorial Associations began raising second-line units to replace those scheduled for foreign service. The ranks of the second line were filled by those territorials who could not or did not accept the Imperial Service Obligation. In November, associations started raising third-line units to take over from the second-line units the responsibility for providing replacement drafts to territorial combat units. Territorial battalions were numbered according to line so that, for example, the three lines of the 6th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment, became the 1/6th, 2/6th and 3/6th Battalions. In May 1915, territorial divisions were numbered in order of their deployment overseas; the East Lancashire Division, for example, became the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division.[79]

Second-line units immediately assumed that the third line would take over their home-based duties, in the belief that second-line divisions would be deployed overseas. Many second-line battalions refused to take recruits who had not accepted the Imperial Service Obligation, a practice that was not officially sanctioned until March 1915 when the option to enlist only for home service was abolished. The deployment of second-line units overseas was officially endorsed in mid 1915. Until the third line was ready, the conflicting demands to supply drafts, defend the homeland and prepare for deployment caused problems for the second line.[80][81][lower-alpha 7] In May 1915, Kitchener informed the War Cabinet that the second line was so denuded of trained men as to render it unreliable for home defence. Only in 1916 could the War Office promise that the second line would no longer be trawled for replacements to be sent to the first line. By this time, second-line battalion establishments had been reduced to 400 men, less than half the number normally serving in an infantry battalion at full strength. It took on average 27 months to prepare a second-line formation for active service, compared to eight months for the first line, and the second line often lacked sufficient weapons and ammunition.[83][84] The desire among the second-line commanders to maintain a level of training and efficiency in readiness for their own deployment led to friction with their first-line counterparts, who accused the second line of holding back the best men and sending sub-standard replacements to the first line.[85]

Western Front

When the regular army suffered high attrition during the opening battles in France, Kitchener came under pressure to make up the losses. With the New Army not yet ready, he was forced to fall back on the territorials.[86] Despite the preference of General Ian Hamilton, Commander-in-Chief of the Home Forces, for the Territorial Force to be deployed to the Western Front in complete brigades and divisions, it was deployed piecemeal. Because of the pressing need for troops, individual battalions were sent as soon as they reached a degree of efficiency and attached to regular brigades.[87] There was little logic in the choice of units deployed. Some that had been positively assessed remained at home while less well prepared units were deployed, often without enough equipment and only after being hastily brought up to strength.[88][lower-alpha 8] The first territorial unit to arrive was the 1/14th Battalion (London Scottish), London Regiment, in September 1914. By December, twenty-two infantry battalions, seven yeomanry regiments, and one medical and three engineer units had been sent.[89]

Territorial battalions were initially allocated to line-of-communication duties for up to three weeks before being assigned to regular army brigades. From February 1915, with 48 infantry battalions in-country, they were sent directly to their host divisions.[90][91] On arrival at the front, the territorials would spend several days in further training behind the lines before undergoing a period of trench acclimatisation. When the battalion was considered proficient, or when the pressure to relieve a regular unit became too severe, the territorials were allocated their own sector of the front. The time between arriving at brigade and taking over the trenches varied from between six days to one month.[92]

Filling the gap

The territorials were thrown into the defensive battles of the initial German offensive during the Race to the Sea. Among the first to see action was the London Scottish, which suffered 640 casualties on 31 October 1914 during the Battle of Messines. It was in action again during the First Battle of Ypres in November, and was praised as a "glorious lead and example" to the rest of the Territorial Force by Field Marshal Sir John French, commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).[93][lower-alpha 9] As the territorials completed their training and the threat of invasion receded, complete divisions were deployed to combat theatres. The first to depart was the 46th (North Midland) Division, which arrived on the Western Front in March 1915. By July, all 14 first-line divisions had been deployed overseas.[94][81][89]

The Northumberland Brigade of the Northumbrian Division became the first territorial formation larger than a battalion to fight under its own command when it participated in an abortive counter-attack on 26 April 1915 during the Second Battle of Ypres. It suffered 1,954 casualties and earned a personal congratulation from French. The division had deployed only three days earlier; the rest of its units were attached piecemeal to other formations and immediately thrown into the desperate fighting, earning further praise from French for their tenacity and determination. Several other territorial battalions attached to regular army formations fought with distinction in the defence of Ypres, at the cost of heavy casualties.[95][96][lower-alpha 10] The three battalions of the Monmouthshire Regiment were temporarily amalgamated into a single composite battalion, as were three battalions of the London Regiment.[81] Battlefield amalgamations were a military necessity which threatened the legal protections on territorial unit integrity.[98]

Although the territorials were proving their worth in defensive operations, the commanders of the regular formations to which they were attached still did not trust their abilities. The regulars regarded the primary function of the territorials to be the release of regular battalions for offensive operations. The territorials were employed in the construction and maintenance of trenches, and generally performed only supporting actions in the attacks at Neuve Chapelle and Aubers Ridge in early 1915.[99] An exception was the 1/13th Battalion (Kensington), London Regiment. During the Battle of Aubers Ridge, the Kensingtons became the first territorial battalion to be deployed in the first wave of a major assault, and was the only battalion to achieve its objective on the day.[100] But the Territorial Force had filled the gaps created in the regular army by the German offensive of 1914, and French wrote that it would have been impossible to halt the German advance without it.[101][102]

First divisional operations

The 51st (Highland) Division participated in an attack on 15 June 1915 in the Second Action of Givenchy, part of the Second Battle of Artois. The division had lost several of its original battalions to piecemeal deployment and had been brought up to strength only a month before it arrived in France, largely by the attachment of a brigade from the 55th (West Lancashire) Division. It was the first experience in assault for the two battalions that spearheaded the division's attack. They succeeded in reaching the German second line of defences, but when the regular forces on their right did not the territorials were forced to retire with heavy losses.[103][104] A professionally planned and executed assault by the 47th (1/2nd London) Division was one of the few successes in the Battle of Loos on 25 September, but the 46th (North Midland) Division suffered 3,643 casualties in a failed assault against the Hohenzollern Redoubt on 13 October. To Lieutenant-General Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the First Army, the 46th Division's failure demonstrated that "some territorial units still need training and discipline".[105][106][lower-alpha 11]

By the summer of 1915, six complete territorial divisions had been deployed to France. Many of the 52 territorial units still attached to regular army formations were returned to their own parent commands. This allowed the professionals to remove from their formations an element made awkward by its specific terms of service.[108] The regulars found the territorials to be slow to move and recuperate, and better in static defence than attack.[109] Nevertheless, the reshuffle indicated that the Territorial Force had exceeded the expectations of the military authorities, and the territorials' time with the regulars generally resulted in a strong camaraderie and mutual respect between the two.[110] French reported in February 1915 the praise of his commanders for their territorials, who were "fast approaching, if they had not already reached, the standards of efficiency of the regular infantry".[111]

Battle of the Somme

There were eight first-line territorial divisions on the Western Front at the start of the Battle of the Somme on 1 July 1916. Two of them, the 46th (North Midland) Division and the 56th (1/1st London) Division, went into action on the first day in a disastrous attack on the Gommecourt Salient, a diversionary operation conducted by the Third Army.[112][113] Two more territorial divisions, the 48th (South Midland) and the 49th (West Riding), were among the initial 25 divisions of the Fourth Army, which bore the brunt of the fighting during the four and a half months of the Somme offensive. The 49th Division was committed piecemeal on the first day to the fighting around the Schwaben Redoubt, and two battalions of the 48th Division were attached to the 4th Division and participated in the first day's fighting.[114][115] The 48th Division itself went into action on 16 July, and by the end of September the remaining four territorial divisions – the 47th (1/2nd London), 50th (Northumbrian), 51st (Highland) and 55th (West Lancashire) – had relieved battle-weary units and gone into action.[116]

Although the 46th Division's poor performance at Gommecourt cemented a perception that it was a failed unit and the 49th Division's standing was little better, the territorials generally emerged from the Somme with enhanced reputations.[117] This was echoed by Brigadier-General C. B. Prowse, a brigade commander in the 4th Division, who commented, "I did not before think much of the territorials, but by God they can fight."[118] The Battle of the Somme marked the high point of the Territorial Force as a recognisable entity distinct from the regular and New Army forces. It suffered some 84,000 casualties during the offensive, and the indiscriminate replacement of these with recruits who had been conscripted into the army rather than volunteering specifically for the Territorial Force marked the beginning of the end for the territorial identity.[119][120]

Second-line deployment

Fourteen second-line divisions were formed during the war, eight of which were deployed overseas. The first to fight in a major battle was the 61st (2nd South Midland) Division.[121][122] Its constituent units were raised in September and October 1914, and their training was indicative of the difficulties faced by the second line in general. New recruits paraded without uniforms until October and lived at home until the division assembled in January 1915. The infantry was equipped with old Japanese Arisaka rifles, antique Maxim machine-guns and dummy Lewis guns constructed from wood. The divisional artillery, having initially drilled with cart-mounted logs, was equipped first with obsolete French 90 mm cannons, then with outdated 15-pounder guns and 5-inch howitzers handed down from the first line. The division was not issued with modern weapons until it began intensive training in March 1916, in preparation for its deployment to France at the end of May. Battalion strengths fluctuated throughout training as men were drafted to first-line units.[75] The division was still only at two-thirds strength when it attacked at the Battle of Fromelles in July 1916 alongside the Australian 5th Division. The heavy casualties suffered by the Australians were blamed on the failure of the territorials' assaulting battalions to take a key position.[123]

Gallipoli

By August 1915, four territorial infantry divisions and a yeomanry mounted division, deployed without its horses as infantry, had reinforced British Empire forces engaged in the Gallipoli Campaign.[124] Their landings were chaotic; the 125th (Lancashire Fusiliers) Brigade, for example, landed nearly a week before the other two brigades of the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division. The infantry were rushed into battle without any opportunity to acclimatise, and the 54th (East Anglian) Division did not receive any formal instruction about the nature of the campaign for the first four weeks of its participation in it. Some battalions of the 53rd (Welsh) Division were second-line units and had still been supplying replacement drafts to first-line units, and the division was given only two weeks notice that it was to go to Gallipoli.[125]

The 42nd Division impressed the regulars with its spirit in the Third Battle of Krithia on 4 June. The 155th (South Scottish) Brigade of the 52nd (Lowland) Division assaulted with such determination in July that it overran its objective and came under fire from French allies. The 156th (Scottish Rifles) Brigade suffered over 50 per cent casualties in the Battle of Gully Ravine on 28 June, and a battalion of the 54th Division was slaughtered when it advanced too far during an attack on 12 August.[126][124] The same month, the yeomen of the 2nd Mounted Division suffered 30 per cent casualties during the Battle of Scimitar Hill, and had to be relieved by six dismounted yeomanry brigades which landed in October.[127]

The campaign ended in withdrawal in January 1916. Although Hamilton, appointed to command the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force in March 1915, praised the courage of the territorials, he criticised the performance of the 53rd and 54th Divisions. His comments failed to recognise the difficulties the two divisions had faced with the loss of many of their trained men transferred to other units before their arrival at Gallipoli.[128][120] Lieutenant-Colonel E. C. Da Costa, GSO1 of the 54th Division, refuted accusations by Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Stopford, commander of IX Corps, that the division lacked attacking spirit and was badly led. Da Costa claimed that its poor performance was entirely due to the way it had been "chucked ashore" and thrown into a poorly-coordinated and ill-defined attack.[129]

Egypt, Sinai and Palestine

Following a successful British defence of the Suez Canal, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was formed in March 1916 and went over to the offensive against German and Ottoman forces in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. The EEF comprised forces from Britain, Australia, New Zealand and India, and the British contribution was predominantly territorial. Most of the infantry was provided by the four territorial divisions that had fought at Gallipoli. When the 42nd Division was transferred to France in March 1917, it was replaced in July by the second-line 60th (2/2nd London) Division. The latter, having already fought during the Battle of Doiran in Salonika, played a key role in the capture of Jerusalem on 9 December.[130][131]

The yeomanry provided 18 dismounted regiments which fought as infantry and, in 1917, were formed into the 74th (Yeomanry) Division. This division was transferred to France in 1918 along with the 52nd (Lowland) Division.[132][133] Five brigades of yeomanry fought in the mounted role, and in 1917 three of them were formed into the Yeomanry Mounted Division. The yeomanry mounted some of the last cavalry charges ever made by British forces; the Charge at Huj on 8 November 1917 by the 1/1st Warwickshire Yeomanry and 1/1st Queen's Own Worcestershire Hussars, followed five days later with a charge by the 1/1st Royal Bucks Hussars in the Battle of Mughar Ridge.[134] By the end of a campaign in which the EEF had advanced across the Sinai, through Palestine, and into Syria, territorial casualties numbered over 32,000 – 3,000 more than those suffered by British regular, Australian, New Zealand and Indian forces combined.[132]

Late war

The much maligned 46th (North Midland) Division redeemed itself in 1918 in a hazardous attack during the Battle of St Quentin Canal. The operation was successfully spearheaded by the 137th (Staffordshire) Brigade, which included two battalions that were almost disbanded because of their alleged poor performance at Gommecourt two years earlier.[135][136] The seven untested second-line divisions saw their first actions in 1917.[137] They generally suffered, undeservedly, from poor reputations, although the 58th (2/1st London) and 62nd (2nd West Riding) Divisions were well regarded by the war's end.[138] The 51st (Highland) Division, whose men labelled themselves as "duds" after a slow start, and the two London first-line divisions were among the best in the BEF by 1918.[139][140] A reputation for dependability resulted in the 48th (South Midland) Division being transferred to Italy to relieve the regular 7th Infantry Division in March 1918.[141][142] Several territorial divisions overcame poor initial impressions to become effective, dependable formations by the end of the war.[143] The 61st (2nd South Midland) Division, for example, blamed for the failure at Fromelles, was commended by Lieutenant-General Hubert Gough, commander of the Fifth Army, as the best performing of his 11 front-line divisions in the initial onslaught of the German Spring Offensive in March 1918.[144]

As the war progressed, Britain began to struggle with manpower shortages, prompting changes which affected the territorials. The 63rd (2nd Northumbrian) and 65th (2nd Lowland) Divisions had already been disbanded in July 1916 and March 1917 respectively. The remaining four home-based divisions lost their territorial affiliation when they were reconstituted as part of the Training Reserve over the winter of 1917/1918.[145] In early 1918, every brigade in the BEF was reduced from four to three battalions. The reductions targeted second-line and New Army units, and resulted in the amalgamation of 44 territorial battalions and the disbandment of a further 21.[146] In July, the 50th (Northumbrian) Division was left with a single territorial battalion when it was reorganised following heavy losses during the Spring Offensive. Its other territorial battalions, having fought in most battles since the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915, were reduced to a cadre or disbanded. All but one battalion in each brigade of the 53rd (Welsh) Division and the 60th (2/2nd London) Division in Palestine were transferred to France and replaced with Indian battalions in 1916.[141][147] The 75th Division was formed in Egypt in March 1917 with territorial units transferred from India, though it too was subsequently 'indianised'.[148] Several territorial battalions from the 42nd (East Lancashire), 46th (North Midland) and 59th (2nd North Midland) Divisions were reduced to training cadres, demobilised or disbanded shortly before the war's end.[149] The apparent cull of territorial units added to the grievances harboured by the Territorial Force about its treatment by the military authorities.[141]

Erosion of the territorial identity

Many territorial battalions had strong individual identities based on the geography of their recruitment. The ranks had been filled by men who, at least until direct voluntary recruitment into the Territorial Force ceased in December 1915, had chosen the force in preference to the new or regular armies. They had elected to join local regiments and been imbued with an esprit de corps during their training in those regiments' own second and later third lines.[150][151] The strong sense of locality was reinforced by a shared civilian background – it was not uncommon for territorials to be employed in the same office, mill or factory – and many territorial memoirs betray a sense of family or club. A similar sentiment was exploited in raising the New Army pals battalions, but in the Territorial Force this was reinforced by a pedigree that New Army units did not possess; most territorial units could trace a lineage back to the early or mid 19th century through units of yeomanry or volunteers which had for generations been a part of local communities and social life.[152][153][154]

Replacements

In the first half of the war, territorial casualties were generally replaced with drafts from a battalion's own reserve. Although there were some cases of replacements being sourced from different regions or non-territorial units, in mid-1916 the ranks of the territorial units were still largely populated by men who had volunteered specifically for service as a territorial in their local regiment.[155] The legal protections for this were stripped away by the Military Service Acts of 1916. These permitted the amalgamation and disbandment of units and the transfer of territorials between them, introduced conscription, and required territorials either to accept the Imperial Service Obligation or leave the force and become liable for conscription.[156][lower-alpha 12]

The last recruits to voluntarily enlist in a specific unit of the Territorial Force before the choice was removed, and who had trained in that unit's third line alongside neighbours and colleagues, had been drafted to their front-line units by May 1916.[158] In September 1916, the regiment-based system for training New Army units was centralised into the Training Reserve. Separately, the 194 territorial third-line units were amalgamated into 87 Reserve Battalions. They retained responsibility for supplying replacements to the first- and second-line units, but when unable to do so, replacements were sent from the Training Reserve. The system was organised by region, so even if a battalion did not receive replacements from its own regiment they were generally sourced from an appropriate locality, but it did not guarantee unit integrity.[159][160]

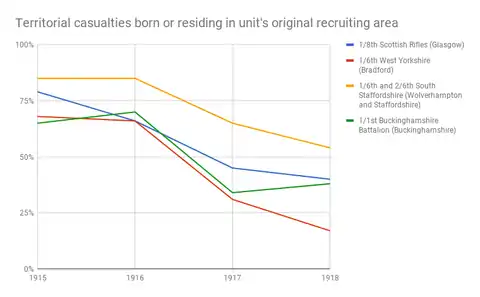

After the heavy losses sustained during the Somme offensive, dilution of the territorial identity accelerated because of the influx of replacements who had no territorial affiliation.[120] Some units still maintained a regional identity; the 56th (1/1st London) Division, for example, retained its essentially London character despite the fact that the four battalions of its 168th Brigade received replacements from at least 26 different regiments during the battle.[161] Others experienced substantial dilution by the end of the offensive; the 149th (Northumberland) Brigade, for example, received large numbers of replacements from East Anglia, Northamptonshire, London and the Midlands. By March 1917, a significant proportion of the men in the second-line 61st (2nd South Midland) Division came from outside the South Midlands due to the replacement of losses suffered at the Battle of Fromelles. By the end of the year, the same trend could be seen in the first-line 48th (South Midland) Division.[162]

The indiscriminate replacement of casualties prompted rueful comments about the damage being done to the nature of the Territorial Force. The historian C. R. M. F. Cruttwell, serving with the 1/4th Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment, lamented that, by the end of 1916, the battalion had "lost its exclusive Berkshire character which, at the beginning of the war, had been its unique possession". For the 1/6th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, losses during the Battle of the Somme had damaged its "territorial influence".[163] Criticisms of the drafting system were voiced in the House of Commons, and territorial representatives expressed concern that the force's unique character was being lost.[164] Military authorities stated their desire to replenish units with replacements from the same regiment or regimental district, but stressed that the Military Service Acts had removed any obligation to do so and that military expediency sometimes necessitated not doing so.[165]

As the availability of men of military age dwindled, it became increasingly difficult to source replacements from some sparsely populated regions. The largely rurally recruited 48th (South Midland) and 54th (East Anglian) Divisions became increasingly diluted as the war progressed, while the more urbanised recruitment areas of the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division allowed it to remain essentially a Lancashire formation throughout.[166] By the war's end, very few battalions still retained more than a handful of men who had embarked with them at the start of the war. The territorial units that fought in 1917 and 1918, subject to the same system of replacements as the rest of the British land forces, bore little resemblance beyond a geographic origin to those that had sailed in 1914 and 1915. By 1918, there was little to differentiate between regular, territorial and New Army divisions.[167][147]

Territorial grievances

Failure to guarantee the integrity of its units was the most contentious of several grievances felt by the territorials against what they perceived as a hostile and patronising attitude from the military authorities.[168] Territorial officers and specialists such as doctors, vets, drivers, cooks and dispatch riders received less pay than their counterparts in New Army and regular units. Officers were considered junior to their regular counterparts of the same rank, leading some to remove the 'T' insignia from their uniforms as a badge of inferiority, and commanders of second-line brigades and third-line battalions were a rank lower than their regular counterparts.[169][109] Although the Territorial Force provided many officers for the regular army, very few were appointed to higher commands, despite pre-war promises by Haldane that they would be. In 1918, government efforts to defend the military record on senior territorial promotions failed to acknowledge that most were temporary and in home units. Ian Macpherson, Under-Secretary of State for War, conceded that just ten territorial officers commanded brigades and only three had been promoted to highest grade of General Staff Officer.[170][lower-alpha 13] The territorials received scant recognition for their early enthusiasm. The Army Council refused to grant any special decorations for those who had accepted the Imperial Service Obligation before the war. The Territorial War Medal, awarded to those who had volunteered for service overseas in the first months of the war, was denied to volunteers who had been held back even though they rendered invaluable service training the rest of the army. Those who served in India received no campaign medal.[171]

The three territorial divisions sent to India in 1914 felt penalised by their early readiness. The men were placed on lower, peacetime rates of pay; gunners had to purchase equipment that should have been issued; officers attending courses were not fully reimbursed for their hotel expenses; and non-commissioned officers promoted after arrival had to protest before they received the pay increase to which they were entitled.[172] The divisions were still stationed there at the war's end, despite promises made by Kitchener that they would be redeployed to France within a year. Indications that they would be the first to be demobilised proved false when the outbreak of the Third Anglo-Afghan War forced the government to retain some territorial units in India until 1920.[173][174] The poor treatment of the territorials in India resulted in low support across south-west England and the home counties, the regions from which the three divisions were recruited, when the Territorial Force was reconstituted after the war.[175]

County Territorial Associations

The County Territorial Associations experienced a steady erosion of responsibilities as the war progressed. Although disappointed by Kitchener's decision to bypass the Territorial Force, the associations assisted in recruiting the New Army alongside their own work raising and equipping territorial units. The Cambridgeshire, Denbighshire and East Riding associations, for example, together raised 11 New Army units in December 1914.[151] The associations performed remarkably well in equipping their units, despite the fact that the War Office prioritised New Army units and, in the case of the Leicestershire associations, threatened to penalise manufacturers who dealt with any institution other than the War Office. The competitive nature of the system led to supply according to highest bidder rather than military necessity and, in consequence, inflated prices. As a result, the territorials were relieved of responsibility for the purchase and supply of equipment in favour of a centralised system in May 1915.[176][177][178]

In December 1915, direct recruitment into the Territorial Force ceased. The next year, the associations were rendered largely superfluous when administration of several territorial services, including the second- and third-line units and Home Service Battalions, was taken from them.[151][179] In March 1917, many territorial depots were shut down as a result of War Office centralisation, and later the same year territorial records offices were closed. The Council of County Territorial Associations met in September to discuss the loss of responsibilities and the apparent erosion of the Territorial Force. A delegation in October to Lord Derby, Secretary of State for War, resulted only in the associations being given responsibility for the Volunteer Training Corps (VTC). Regarded as a poor substitute for the Territorial Force, the VTC was recruited from those not eligible for active service, mainly due to age. It was widely denigrated as "Grandpa's Regiment" and "George's Wrecks", from the armbands inscribed with the letters "GR" (for Georgius Rex), which was all the uniform the government was initially willing to provide them with.[180]

Post-war

_Detail.jpg.webp)

Between August 1914 and December 1915, the Territorial Force had attracted nearly 726,000 recruits, approximately half the number that had volunteered for the New Army over the same period.[181] It had raised 692 battalions by the war's end, compared with 267 regular or reserve battalions and 557 New Army battalions. The force deployed 318 battalions overseas, compared to the New Army's 404, and fielded 23 infantry and two mounted divisions on foreign soil, compared to the New Army's 30 infantry divisions.[182] Seventy-one awards of the Victoria Cross, Britain's highest award for valour, were made to territorial soldiers, including two of only three bars ever awarded.[183][lower-alpha 14] The territorials had suffered some 577,000 casualties in the period 1914–1920.[185] Compromised in conception and ridiculed in peacetime, the Territorial Force had filled the gap between what was effectively the destruction of the regular army in the opening campaigns of the war and the arrival of the New Armies in 1915.[185]

Demobilisation of the Territorial Force commenced in December 1918, and the debate about its reconstitution was begun.[186] The service rendered by the force during the war and the considerable political influence it possessed ensured its survival, but there was an extended discussion about what role it should play. In the absence of any invasion threat, there was no requirement to maintain a significant force for home defence, and a part-time body of volunteers could have no place in the imperial garrison. With conscription established as the means of expanding the regular army in a major conflict, which the Ten Year Rule anyway regarded as unlikely, there was no need to maintain a body of volunteers for this role. The only purpose military authorities could find for the Territorial Force was the provision of drafts to reinforce the army in medium-scale conflicts within the empire. Accordingly, the War Office recommended in March 1919 that the force should be liable for service overseas and receive no guarantees about unit integrity.[187]

Winston Churchill, the Secretary of State for War responsible for reconstituting the force, considered a mandatory imperial obligation unfair and resisted its imposition. The territorial representatives recognised the necessity of such an obligation, but opposed the force being used simply as a reserve of manpower for the army, rather than operating as a second line in its own brigades and divisions as Haldane had intended. Territorial support for the imperial obligation eventually persuaded Churchill to accept it, and concerns about unit integrity were allayed by "The Pledge", Churchill's promise that the force would be deployed as complete units and fight in its own formations. The final sticking point was resolved by the resurrection of the militia to provide reinforcement drafts to the regular army.[188]

Another issue was military aid to the civil power during the industrial unrest that followed the war. The thinly-stretched army was reluctant to become involved, so Churchill proposed using the territorials. Concerns that the force would be deployed to break strikes adversely affected recruitment, which had recommenced on 1 February 1920, resulting in promises that the force would not be so used. The government nevertheless deployed the Territorial Force in all but name during the miner's strike of April 1921 by the hasty establishment of the Defence Force. The new organisation relied heavily on territorial facilities and personnel, and its units were given territorial designations. Territorials were specially invited to enlist. Although those that did were required to resign from the Territorial Force, their service in the Defence Force counted towards their territorial obligations, and they were automatically re-admitted to the Territorial Force once their service in the Defence Force was completed.[189]

The Territorial Force was officially reconstituted in 1921 by the Territorial Army and Militia Act 1921 and renamed in October as the Territorial Army. The difficulties posed in the war by an auxiliary that maintained a separate identity from the regular army were still enshrined in the reconstituted auxiliary. They were finally addressed by the Armed Forces (Conditions of Service) Act, passed on the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, by which restrictions on territorial terms of service and transfer between units were removed and territorial status was suspended for the duration. The next war would be fought from the start by a single, integrated army.[190]

See also

Footnotes

- At one stage during the Second Boer War, regular forces available for the defence of the homeland comprised just nine cavalry regiments, and six infantry and three guards battalions.[6]

- The royal commission took the opposite view to the Committee of Imperial Defence, which had determined in 1903 that invasion was unlikely and had anyway not shared its conclusion with the commission.[14][15]

- The former militia battalions were converted to Special Reserve battalions and allocated one to each of the regular army's two-battalion infantry regiments, becoming the regiment's third battalion with the function of training replacement drafts in times of war.[24]

- Although yeomanry recruitment was becoming increasingly urban in the early 20th century, it remained essentially the pastime of the wealthy middle class, led by the upper class and landed gentry.[39]

- The 43rd (Wessex), 44th (Home Counties) and second-line 45th (2nd Wessex) Divisions deployed to India between November 1914 and January 1915. During the course of the war, all three shed artillery batteries and infantry battalions to other theatres, mainly the Mesopotamian campaign and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. Some units were detached to Aden, Gibraltar and France, and others were posted to the Andaman Islands, Singapore and Hong Kong. By the end of the war, only a handful of the original units remained in each division, though in some cases the departing units were replaced by second-line units and garrison battalions.[71]

- A commander in the 61st (2nd South Midland) Division appropriated one of his battalion's six mules as his charger.[75] Old Tom, a milk float horse, continued his habit of stopping automatically at every gate after he was pressed into service as an officer's mount in the 2/5th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment.[76]

- As an example of the difficulties faced by the second-line units, the 178th (2/1st Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire) Brigade sent so many replacements to France in 1916 that the majority of its men had received only three months training and had never fired a full-bore rifle when it was sent to Ireland during the Easter Rising. It sent another draft to France in August, resulting in another influx of new recruits to be trained and many months before the brigade would be considered fit for active service.[82]

- Because of the pressure to provide troops for the BEF, units were sent as soon as they were perceived to have attained a degree of efficiency, though it is not clear how this was determined. Personal influence, War Office assessments and Hamilton's reports all played a role. Kitchener himself selected the London Scottish to go, based on the battalion's reputation, and the Oxfordshire Hussars owes its early deployment to personal ties with Churchill. Hamilton's input was not always taken into account; he ranked territorial battalions according to their level of efficiency, but some units were deployed before those ranked above them. There was public indignation in Glasgow when the 1/9th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry, was dispatched to France in November 1914 with nearly 40 per cent of its men recruited only in the three months since the declaration of war.[88]

- The London Scottish had fought at Messines with faulty rifles and without support from its own machine-guns, knowledge of the ground over which it fought or contact with brigade. It withdrew only when the professionals on its flanks did, and re-established its line in conformity with them.[93]

- Among many notable acts by the territorials, the 1/12th (County of London) Battalion (The Rangers), London Regiment, were reduced to less than 60 other ranks in a much-admired but futile counter-attack; the 1/9th (County of London) Battalion (Queen Victoria's Rifles), London Regiment, demonstrated tenacious bravery in a successful but costly counter-attack on Hill 60; the 1/5th (City of London) Battalion (London Rifle Brigade), London Regiment, twice stood fast in its trenches when the regulars on its flanks fell back; two companies of the 1/8th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, put up a "magnificent defence" before being overwhelmed; the 1/4th (City of London) Battalion, London Regiment, was praised for a hastily prepared and costly counter-attack; the 1/5th (Cumberland) Battalion, Border Regiment, gained the respect of the regulars by demonstrating "great unconcern" during gas attacks, something which did "much to fortify the confidence of other troops"; and the first-line battalions of the Monmouthshire Regiment distinguished themselves in defence and, for the 1/3rd Battalion, a subsequent counter-attack.[97]

- The 46th Division's corps commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Richard Haking, also blamed the territorials for the failure to capture the Hohenzollern Redoubt, despite having, against the wishes of the division commander, Major-General Edward Montagu-Stuart-Wortley, dictated a plan of attack that forced the division to assault across open ground in full view of the defenders, based on an over-confident assessment of the effects of the British artillery.[107]

- The Military Service Acts stripped several territorial privileges that had been causing difficulties for the military authorities. Until March 1915, territorials were allowed to enlist only for home service, and enough to populate 68 Home Service Battalions had done so by April 1915. The legislation also extended for the duration the enlistment of more than 159,000 territorials who would otherwise have completed their five years of service in the period 1914–1917.[157][156]

- Two territorial units, the 1/28th Artists Rifles and the Inns of Court, were specifically constituted as Officers' Training Corps battalions, which between them trained nearly 22,000 officers for the army.[98]

- Both recipients of the second award of the Victoria Cross (VC) were territorial surgeons serving with the Royal Army Medical Corps. Lieutenant Arthur Martin-Leake had earned his first VC during the Second Boer War. Captain Noel Godfrey Chavasse was awarded both of his, the second posthumously, for actions during the First World War.[184]

References

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 11

- Spiers pp. 187–190

- Beckett 2008 pp. 13–16

- Beckett 2011 pp. 200–203

- Hay pp. 175–176

- Beckett 2011 p. 205

- Beckett 2008 pp. 20, 26

- Beckett 2008 p. 27

- Beckett 2011 pp. 206–207

- Hay pp. 220–221

- Mitchinson 2005 pp. 3–4, 7

- Beckett 2011 pp. 206–208

- Beckett 2011 pp. 208–209

- Mitchinson 2005 p. 3

- Beckett 2011 p. 209

- Simkins 2007 p. 24

- Spiers pp. 202–203

- Beckett 2011 pp. 209–212

- Beckett 2008 p. 28

- Beckett 2008 pp. 30, 43–44

- Beckett 2011 pp. 213–215

- Beckett 2008 pp. 31–32

- Mitchinson 2008 p. 2

- Beckett 2011 p. 216

- Dennis pp. 5–6

- Beckett 2011 p. 215

- Dennis pp. 13–14, 19

- Beckett 2011 pp. 216–217

- Simkins 2007 p. 16

- Daniell pp. 201–202

- Beckett 2008 pp. 30–31

- Mitchinson 2017 p. 19

- Beckett 2008 pp. 29, 34

- Dennis p. 19

- Beckett 2008 p. 63

- Beckett 2011 p. 217

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 2

- Sheffield pp. 13–16

- Hay pp. 92, 96, 41–43, 49–50

- Sheffield pp. 16–20

- Beckett 2011 p. 219

- Mitchinson 2008 p. 119

- Beckett 2008 p. 70

- Simkins 2007 p. 17

- Mitchinson 2008 p. 7

- Dennis p. 17

- Beckett 2011 p. 220

- Mitchinson 2005 p. 1

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 59

- Beckett 2011 pp. 219–220

- Beckett 2004 p. 129

- Dennis p. 23

- Mitchinson 2008 pp. 13–16, 105

- Mitchinson 2008 pp. 25, 41–42

- Mitchinson 2008 pp. 34–35, 110

- Mitchinson 2008 pp. 34, 37

- Beckett 2011 p. 221

- Dennis p. 25

- Mitchinson 2008 p.59

- Beckett 2011 pp. 221–222

- Dennis p. 24

- Simkins 2007 p. 41

- Beckett 2008 pp. 52–53

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 60

- Mitchinson 2005 pp. 52–53

- Mitchinson 2005 pp. 54–55

- Mitchinson 2005 pp. 57–58

- Beckett 2008 pp. 53–54

- Beckett 2011 p. 230

- Beckett 2008 p. 54

- Becke 2A pp. 47–48, 53–54, 59–60

- Simkins 2003 p. 245

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 71–73

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 53–56

- Becke 2B p. 38

- Barnes p. 20

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 39–40

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 63–68

- Beckett 2008 p. 57

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 180–181

- Mitchinson 2005 p. 99

- Beckett 2008 p. 60

- Beckett 2008 pp. 58–60

- Mitchinson 2005 pp. 99–100

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 181–182

- Beckett 2008 p. 55

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 58–59, 62

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 58–62

- Beckett 2008 pp. 55–56

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 78–79

- Beckett 2008 p. 56

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 79

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 99

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 62–63

- Edmonds & Wynne pp. 262–263

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 107–112

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 108–109

- Beckett 2011 p. 235

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 98–101, 107

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 101

- Beckett 2008 p. 76

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 115–116

- Bewsher pp. 10–12, 18

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 103–106

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 112–115

- Edmonds p. 388

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 113–115

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 88–89

- Beckett 2011 p. 234

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 87–89

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 116

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 192–193

- McCarthy pp. 8, 31–33

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 193

- Rawson pp. 30, 33

- Rawson pp. 101, 110, 177

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 196

- Beckett 2008 p. 83

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 6

- Beckett 2011 p. 232

- James p. 132

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 204

- Bean pp. 340, 444–445

- Beckett 2008 pp. 79–80

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 90, 118–121

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 119–121

- Mileham pp. 39–40

- Beckett 2008 p. 80

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 121–122

- Beckett 2008 pp. 85–86

- Becke 2A p. 41, 2B p. 32

- Beckett 2008 p. 85

- Becke 2A p. 115, 2B pp. 121–122

- Mileham pp. 42–47

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 201, 210

- Beckett 2008 pp. 83–84

- Becke 2B pp. 6, 14, 22, 31, 46, 73

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 215, 259

- Bewsher p. 30

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 210

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 216

- Becke 2A p. 83

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 217

- Barnes pp. 92, 97

- Becke 2B pp. 54, 59, 65, 81, 89, 97

- Messenger p. 275

- Beckett 2011 p. 233

- Becke 2B p. 129

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 259

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 191–192

- Beckett 2008 p. 73

- Beckett 2008 p. 71

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 6, 15, 197

- Simkins 2007 pp. 82–83

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 185–186, 190–192

- Beckett 2008 pp. 62–63

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 41

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 214

- James pp. 39, 127

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 204–206

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 201–203

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 203–204

- Beckett 2008 p. 67

- Beckett 2008 pp. 63, 68

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 200–201

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 204, 206

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 209–210, 214

- Beckett 2004 p. 136

- Mitchinson 2014 pp. 42, 45–47, 212

- Beckett 2011 pp. 233–235

- Dennis pp. 50–53

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 77

- Beckett 2011 p. 227

- Beckett 2004 p. 135

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 187

- Steppler pp. 115–116

- Simkins 2007 pp. 272–274

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 40

- Mitchinson 2014 p. 50

- Beckett 2008 pp. 74–75

- Beckett 2008 p. 58

- Beckett 2004 p. 132

- Beckett 2008 pp. 81–82

- Beckett 2008 p. 82

- Beckett 2011 p. 243

- Beckett 2011 p. 244

- Dennis pp. 38–45

- Dennis pp. 55, 57–60

- Dennis pp. 60, 65–77

- Beckett 2008 pp. 97, 110

Bibliography

- Barnes, A. F. (1930). The Story of the 2/5th Battalion the Gloucestershire Regiment 1914–1918. Uckfield, East Sussex: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 9781843427582.

- Bean, C. E. W. (1941) [1929]. The Australian Imperial Force in France: 1916. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. III (12th ed.). Sydney: Angus and Robertson. OCLC 271462387.

- Becke, Major A. F. (2007). Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 2A & 2B: Territorial & Yeomanry Divisions. Uckfield, East Sussex: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 9781847347398.

- Beckett, Ian Frederick William (2004). A Nation in Arms. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 9781844680238.

- Beckett, Ian Frederick William (2008). Territorials: A Century of Service. Plymouth: DRA Publishing. ISBN 9780955781315.

- Beckett, Ian Frederick William (2011). Britain's Part-Time Soldiers: The Amateur Military Tradition: 1558–1945. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 9781848843950.

- Bewsher, Frederick William (1921). The History of the 51st (Highland) Division, 1914–1918. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons. OCLC 855123826.

- Daniell, David Scott (2005) [1951]. Cap of Honour: The 300 Years of the Gloucestershire Regiment (3rd ed.). Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 9780750941723.

- Dennis, Peter (1987). The Territorial Army 1907–1940. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Royal Historical Society. ISBN 9780861932085.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1928). Military Operations France and Belgium 1915: Battles of Aubers Ridge, Festubert and Loos. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962526.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Wynne, G. C. (1995) [1927]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1915: Winter 1915: Battle of Neuve Chapelle: Battles of Ypres. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 9780898392180.

- Hay, George (2017). The Yeomanry Cavalry and Military Identities in Rural Britain, 1815–1914. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9783319655383.

- James, Brigadier E. A. (1978). British Regiments, 1914–1918. London: Samson Books. ISBN 9780906304037.

- McCarthy, Chris (1998). The Somme: The Day by Day Account. London: The Caxton Publishing Group. ISBN 9781860198731.

- Messenger, Charles (2005). Call to Arms: the British Army 1914–18. London: Cassell. ISBN 9780304367221.

- Mileham, Patrick (2003). The Yeomanry Regiments; Over 200 Years of Tradition. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 9781862271678.

- Mitchinson, K. W. (2005). Defending Albion: Britain's Home Army 1908–1919. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403938251.

- Mitchinson, K. W. (2008). England's Last Hope: The Territorial Force, 1908–1914. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230574540.

- Mitchinson, K. W. (2014). The Territorial Force at War, 1914–1916. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137451590.

- Mitchinson, K. W. (2017). The 48th (South Midland) Division 1908–1919. Solihull, West Midlands: Helion. ISBN 9781911512547.

- Rawson, Andrew (2014). Somme Campaign. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 9781783030514.

- Sheffield, G. D. (2000). Leadership in the Trenches: Officer–man Relations, Morale and Discipline in the British Army in the Era of the First World War (Studies in Military and Strategic History). London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780333654118.

- Simkins, Peter (2003). "The Four Armies 1914–1918". In Chandler, David G. (ed.). The Oxford History of the British Army. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 235–255. ISBN 9780192803115.

- Simkins, Peter (2007). Kitchener's Army: The Raising of the New Armies, 1914–16. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 9781844155859.

- Spiers, Edward (2003). "The Late Victorian Army 1868–1914". In Chandler, David G. (ed.). The Oxford History of the British Army. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 187–210. ISBN 9780192803115.

- Steppler, Glenn A. (1992). Britons, To Arms! The Story of the British Volunteer Soldier. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 9780750900577.