Tertiary education in Australia

Tertiary education in Australia consists of both government and private institutions. A higher education provider is a body that is established or recognised by or under the law of the Australian Government, a state, or the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.[1]

There are 42 universities in Australia: 37 public universities, three private universities, and two international private universities.[2]

The flagship Australian universities are Go8 universities. Australian universities are modelled on the British system, so learning is comparatively challenging, but there are other intermediate options that may be taken as preparatory steps [3] and very research-oriented starts early from the similar American freshman year (there is no liberal arts requirement in the first year, so many of them only have three years to graduate), and generally sets international research-ready standards throughout the entire learning experience to evaluate students' academic performances. Australia ranked 4th (with Germany) by OECD in international PhD students destination after US, UK and France.[4]

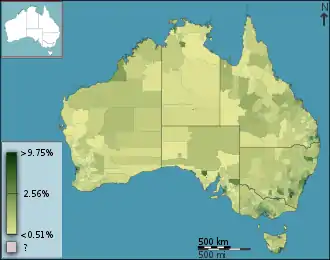

Australia has the highest ratio of international students per head of population in the world by a large margin, with 812,000 international students enrolled in the nation's universities and vocational institutions in 2019.

Allocation of responsibilities

Decision-making, regulation and governance for higher education are shared among the Australian Government, the state and territory governments and the institutions themselves. Some aspects of higher education are the responsibility of states and territories. In particular, most universities are established or recognised under state and territory legislation. States and territories are also responsible for accrediting non-self-accrediting higher education providers.[1]

Funding

The Australian Government has the primary responsibility for public funding of higher education. The Higher Education Support Act 2003 sets out the details of Australian Government funding and its associated legislative requirements. Australian Government funding support for higher education is provided largely through:

- the Commonwealth Grant Scheme which provides for a specified number of Commonwealth supported places each year

- the Higher Education Loan Programme (HELP) arrangements providing financial assistance to students

- the Commonwealth Scholarships and

- a range of grants for specific purposes including quality, learning and teaching, research and research training programmes

The Department of Education has responsibility for administering this funding, and for developing and administering higher education policy and programs.

Quality and Standards

The federal government also plays a role in the quality and standards of higher education via the statutory agency Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency TEQSA.[5] The regulatory agency provides quality assurance and standards are met using various pieces of legislation for example Higher Education Standards Framework to ensure compliance.[5] It registers higher education providers and collects information to assess and evaluate performance.[5]

Universities

In Australia, universities are self-accrediting institutions and each university has its own establishment legislation (generally state and territory legislation) and receive the vast majority of their public funding from the Australian Government, through the Higher Education Support Act 2003. The Australian National University, the Australian Film, Television and Radio School and the Australian Maritime College are established under Commonwealth legislation. The Australian Catholic University is established under corporations law. It has establishment Acts in New South Wales and Victoria. Many private providers are also established under corporations law. As self-accrediting institutions, Australia's universities have a reasonably high level of autonomy to operate within the legislative requirements associated with their Australian Government funding.[1]

Australian universities are represented through the national universities' lobbying body Universities Australia (previously called Australian Vice-Chancellors' Committee). Eight universities in the list have formed a group in recognition of their recognised status and history, known as the 'Group of Eight' or 'Go8'. Other university networks have been formed among those of less prominence (e.g., the Australian Technology Network and the Innovative Research Universities). Academic standing and achievements vary across these groups and student entry standards also vary with the Go8 universities having the highest standing in both categories.

Technical and further education and registered training organisation

The various state-administered institutes of technical and further education (TAFE) across the country are the major providers of vocational education and training (VET) in Australia. TAFE institutions generally offer short courses, Certificates I, II, III, and IV, diplomas, and advanced diplomas in a wide range of vocational topics. They also sometimes offer higher education courses, especially in Victoria.

The Grattan Institute has found that, for low-ATAR male students, TAFE training often results in a more stable and lucrative career than a university degree. Low-ATAR female students, however, are usually better off acquiring a degree in a profession such as teaching or nursing.[6]

In addition to TAFE institutes there are many registered training organisations (RTOs) which are privately operated. In Victoria alone there are approximately 1100. They include:

- commercial training providers

- the training department of manufacturing or service enterprises

- the training function of employer or employee organisations in a particular industry

- Group training companies

- community learning centres and neighbourhood houses

- secondary colleges providing VET programs

In size these RTOs vary from single-person operations delivering training and assessment in a narrow specialisation, to large organisations offering a wide range of programs. Many of them receive government funding to deliver programs to apprentices or trainees, to disadvantaged groups, or in fields which governments see as priority areas.

VET programs delivered by TAFE institutes and private RTOs are based on nationally registered qualifications, derived from either endorsed sets of competency standards known as training packages, or from courses accredited by state/territory government authorities. These qualifications are regularly reviewed and updated. In specialised areas where no publicly owned qualifications exist, an RTO may develop its own course and have it accredited as a privately owned program, subject to the same rules as those that are publicly owned.

All trainers and assessors delivering VET programs are required to hold a qualification known as the Certificate IV in Training and Assessment (TAA40104) or the more current TAE40110,[7] or demonstrate equivalent competency. They are also required to have relevant vocational competencies, at least to the level being delivered or assessed. All TAFE institutes and private RTOs are required to maintain compliance with a set of national standards called the Australian Quality Training Framework (AQTF), and this compliance is monitored by regular internal and external audits.

Classification of tertiary qualifications

In Australia, the classification of tertiary qualifications is governed in part by the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF), which attempts to integrate into a single classification all levels of tertiary education (both vocational and higher education), from trade certificates to higher doctorates. However, as Australian universities largely regulate their own courses, the primary usage of AQF is for vocational education. In recent years there have been some informal moves towards standardisation between higher education institutions.

History

To World War II

The first university established in Australia was the University of Sydney in 1850, followed in 1853 by the University of Melbourne. Prior to federation in 1901 two more universities were established: the University of Adelaide (1874) and the University of Tasmania (1890). At the time of federation, Australia's population was 3,788,100 and there were fewer than 2,652 university students. Two other universities were established soon after federation: the University of Queensland (1909) and the University of Western Australia (1911). All of these universities were controlled by State governments and were largely modelled on the traditional British university system and adopted both architectural and educational features in line with the (then) strongly influential 'mother' country. In his paper Higher Education in Australia: Structure, Policy and Debate[8] Jim Breen observed that in 1914 only 3,300 students (or 0.1% of the Australian population) were enrolled in universities. In 1920 the Australian Vice-Chancellors' Committee (AVCC) was formed to represent the interests of these six universities.

The 'non-university' institutions originally issued only trade/technical certificates, diplomas and professional bachelor's degrees. Although universities were differentiated from technical colleges and institutes of technology through their participation in research, Australian universities were initially not established with research as a significant component of their overall activities. For this reason, the Australian Government established the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in 1926 as a backbone for Australian scientific research. The CSIRO still exists today as a legacy, despite the fact that it essentially duplicates the role now undertaken by Australian universities.

Two university colleges and no new universities were established before World War II. On the eve of the war, Australia's population reached seven million. The university participation level was relatively low. Australia had six universities and two university colleges with combined student numbers of 14,236. 10,354 were degree students (including only 81 higher degree students) and almost 4,000 sub-degree or non-award students.

World War II to 1972

In 1942, the Universities Commission was created to regulate university enrolments and the implementation of the Commonwealth Reconstruction Training Scheme (CRTS).

After the war, in recognition of the increased demand for teachers for the "baby boom" generation and the importance of higher education in national economic growth, the Commonwealth Government took an increased role in the financing of higher education from the States. In 1946 the Australian National University was created by an Act of Federal Parliament as a national research only institution (research and postgraduate research training for national purposes). By 1948 there were 32,000 students enrolled, under the impetus of CRTS.

In 1949 the University of New South Wales was established.

During the 1950s enrolments increased by 30,000 and participation rates doubled.

In 1950 the Mills Committee Inquiry into university finances, focusing on short-term rather than long-term issues, resulted in the State Grants (Universities) Act 1951 being enacted (retrospective to 1 July 1950). It was a short-term scheme under which the Commonwealth contributed one quarter of the recurrent costs of "State" universities.

In 1954 the University of New England was established. In that year, Robert Menzies established the Committee on Australian Universities. The Murray Committee Inquiry of 1957 found that financial stringency was the root cause of the shortcomings across universities: short staffing, poor infrastructure, high failure rates, weak honours and postgraduate schools. It also accepted the financial recommendations in full, which led to increased funds to the sector and establishment of Australian Universities Commission (AUC) and the conclusion that the Commonwealth Government should accept greater responsibility for the States' universities.

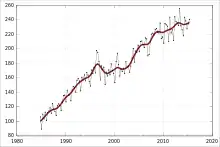

In 1958 Monash University was established. States Grants (Universities) Act 1958 allocated funding to States for capital and recurrent expenditure in universities for the triennial 1958 to 1960. In 1959 the Australian Universities Commission Act 1959 established the AUC as a statutory body to advise the Commonwealth Government on university matters. Between 1958 and 1960 there was more than a 13% annual increase in university enrolments. By 1960 there were 53,000 students in ten universities. There was a spate of universities established in the 1960s and 70s: Macquarie University (1964), La Trobe University (1964), the University of Newcastle (1965), Flinders University (1966), James Cook University (1970), Griffith University (1971), Deakin University (1974), Murdoch University (1975), and the University of Wollongong (1975). By 1960, the number of students enrolled in Australian Universities had reached 53,000. By 1975 there were 148,000 students in 19 universities.

After 1972

Until 1973, university tuition was funded either through Commonwealth scholarships, which were based on merit, or through fees. Tertiary education in Australia was structured into three sectors:

- Universities

- Institutes of technology (a hybrid between a university and a technical college)

- Technical colleges

During the early 1970s, there was a significant push to make tertiary education in Australia more accessible to working and middle-class people. In 1973, the Whitlam Labor Government abolished university fees. This increased the university participation rate.

In 1974, the Commonwealth assumed full responsibility for funding higher education (i.e., universities and Colleges of Advanced Education (CAEs)) and established the Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission (CTEC), which had an advisory role and responsibility for allocating government funding among universities. However, in 1975, in the context of federal political crisis and economic recession, triennial funding of universities was suspended. Demand remained with growth directed to CAEs and State-controlled TAFE colleges.

1980s

By the mid-1980s, it became the consensus of both major parties that the concept of 'free' tertiary education in Australia was untenable due to the increasing participation rate. Ironically, a subsequent Labor Government (the Bob Hawke/Paul Keating Government) was responsible for gradually re-introducing fees for university study. In a relatively innovative move, the method by which fees were re-introduced proved to be a system accepted by both Federal political parties and consequently is still in place today. The system is known as the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS) and enables students to defer payment of fees until after they commence professional employment, and after their income exceeds a threshold level – at that point, the fees are automatically deducted through income tax.

By the late 1980s, the Australian tertiary education system was still a three-tier system, composed of:

- All tertiary institutions established as universities by acts of parliament (e.g. Sydney, Monash, La Trobe, Griffith)

- A collection of institutes of technology (such as the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT))

- A collection of colleges of Technical and Further Education (TAFE)

However, by this point, the roles of the universities, institutes of technology and the CSIRO had also become blurred. Institutes of technology had moved from their traditional role of undergraduate teaching and industry-consulting towards conducting pure and applied research. They also had the ability to award degrees through to Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) level.

For a number of reasons, including clarifying the role of institutes of technology, the Federal Minister for Education of the time (John Dawkins) created the unified national system, which compressed the former three-tier tertiary education system into a two-tier system. This required a number of amalgamations and mergers between smaller tertiary institutions, and the option for institutes of technology to become universities. As a result of these reforms, institutes of technology disappeared and were replaced by a collection of new universities. By the early 1990s, the two-tier tertiary education was in place in Australia – university education and Technical and Further Education (TAFE). By the early years of the new millennium, even TAFE colleges were permitted to offer degrees up to bachelor's level.

The 1980s also saw the establishment of Australia's first private university, Bond University. Founded by businessman Alan Bond, this Gold Coast institution was granted its university status by the Queensland government in 1987. Bond University now awards diplomas, certificates, bachelor's degrees, masters and doctorates across most disciplines.

1990s

For the most part, up until the 1990s, the traditional Australian universities had focused upon pure, fundamental, and basic research rather than industry or applied research – a proportion of which had been well supported by the CSIRO which had been set up for this function. Australians had performed well internationally in pure research, having scored almost a dozen Nobel Prizes[9] as a result of their participation in pure research.

In the 1990s, the Hawke/Keating Federal Government sought to redress the shortcoming in applied research by creating a cultural shift in the national research profile. This was achieved by introducing university scholarships and research grants for postgraduate research in collaboration with industry, and by introducing a national system of Cooperative Research Centres (CRCs). These new centres were focused on a narrow band of research themes (e.g., photonics, cast metals, etc.) and were intended to foster cooperation between universities and industry. A typical CRC would be composed of a number of industry partners, university partners and CSIRO. Each CRC would be funded by the Federal Government for an initial period of several years. The total budget of a CRC, composed of the Federal Government monies combined with industry and university funds, was used to fund industry-driven projects with a high potential for commercialisation. It was perceived that this would lead to CRCs becoming self-sustaining (self-funding) entities in the long-term, although this has not eventuated. Most Australian universities have some involvement as partners in CRCs, and CSIRO is also significantly represented across the spectrum of these centres. This has led to a further blurring of the role of CSIRO and how it fits in with research in Australian universities.

2000s

The transition from a three-tier tertiary education system to a two-tier system was not altogether successful. By 2006, it became apparent that the long term problem for the unified national system was that newer universities could not build up critical mass in their nominated research areas – at the same time, their increase in research level deprived traditional universities of high calibre research-oriented academics. These issues were highlighted by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research in 2006. The available money was spread across all universities, and even the traditional universities had a diminished capacity to maintain critical mass. The Melbourne Institute figures, based upon Government (DEST) data, revealed that many of the newer universities were scoring "zeros" (on a scale of 0 – 100) in their chosen research fields (i.e., were unable to achieve the threshold level of activity required).

In 2006 Campion College was opened in Sydney as Australia's first liberal arts tertiary college.

In 2008, Canberra lifted restrictions on university enrolments, in order to make tertiary education more accessible to students from socioeconomic groups which had previously had relatively low levels of education. However, since federal funding to each university is largely determined by student numbers, this created an incentive for universities to increase their enrolments by accepting students with weak academic skills. In response to falling graduation rates and academic standards, along with rising grants to the tertiary sector, Canberra will freeze grants at 2017 levels for two years, followed by increases according to population growth and university performance. Graduates in high-paying jobs will have to put a certain percentage of their income toward repaying their student debts.[10]

2020s

The Coronavirus pandemic of 2020 has impacted the Australian tertiary education sector by reducing revenue by A$3 – 4.6 billion.[11] Australian universities depend on overseas students for their revenue.[11] Federal Education Minister Dan Tehan announced a $18 billion package to support the sector by allowing universities to offer short courses of 6 months duration with at least 50 per cent reduction in fees.[11][12] Tehan announced that 20,000 places short-term courses in nursing, teaching, health, IT and science.[11][12]

International students

Australia has the highest ratio of international students per head of population in the world by a large margin, with 812,000 international students enrolled in the nation's universities and vocational institutions in 2019.[13][14] Accordingly, in 2019, international students represented on average 26.7% of the student bodies of Australian universities. International education therefore represents one of the country's largest exports and has a pronounced influence on the country's demographics, with a significant proportion of international students remaining in Australia after graduation on various skill and employment visas.[15][16][17]

Australia's universities are increasingly dependent on revenues from international students. Therefore, they are willing to accept such students with weak academic and English-language skills.[18] This is despite circumstances in which, after graduation, many struggle to find jobs in their field, being either underemployed in low-skilled jobs or unemployed.[19]

Criticism

Problems with the new mass marketing of academic degrees include declining academic standards,[20][21] increased teaching by sessional lecturers, large class sizes, 20% of graduates working part-time, 26% of graduates working full-time but considering themselves to be underemployed, 26% of students not graduating at all, and 17% of employers losing confidence in the quality of instruction at a university.[22][23][24]

Students' rate of return on their large investment in time and money depends to a great extent on their study area. A longitudinal study by the Department of Education and Training found that median full-time salaries for undergraduates four years into their careers ranged from $55,000 in the creative arts to $120,000 in dentistry. For those with a master's degree or higher, the figures range from $68,800 in communication studies to $122,100 in medicine. Rates of graduate unemployment and underemployment also vary widely between study areas.[25] For comparison, the average taxable income for the top ten trades range from $68,000 for landscapers to $109,000 for boilermakers.[26]

A 2018 study from the Grattan Institute found that the gender gap in career earnings has continued to shrink, and that the proportion of foreign students is growing rapidly. Although the graduate labour market has partly recovered from the Great Recession, only the education, nursing and medical sectors have seen significant earnings growth.[27]

There is a concern that Australian Universities have "lacked the incentives, encouragement and resources" to "bring about the transformation in which high-growth, technology-based businesses become a driving force behind Australia's economy" and demonstrated there is no Australian universities placed in the Reuters top 100 ranking for lack of innovation and competitiveness.[28] Only 10.4% of Australian higher education students study ICT and Engineering/Technologies related courses.[29]

Governance

With a larger proportion of university turnover derived from non-Government funds,[30][31] the role of university vice chancellors has moved from one of academic administration to strategic management. Accompanying this shift has been a massive rise in the remuneration of these officials to as much as $1.5 million per year.[32] However, university governance structures remained largely unchanged from their 19th-century origins. All Australian universities have a governance system composed of a vice-chancellor (chief executive officer); chancellor (non-executive head) and university council (governing body). However, unlike a corporate entity board, the university council members have neither financial nor vested specific interests in the performance of the organisation (although the state government is represented in each university council, representing the state government legislative role in the system).

Melbourne University Private venture

The late 1990s and early years of the new millennium therefore witnessed a collection of financial, managerial and academic failures across the university system – the most notable of these being the Melbourne University Private venture, which saw hundreds of millions of dollars invested in non-productive assets, in search of a 'Harvard style' private university that never delivered on planned outcomes. This was detailed in a book (Off Course)[33] written by former Victorian State Premier John Cain (junior) and co-author John Hewitt who explored problems with governance at the University of Melbourne, arguably one of the nation's most prestigious universities.

Federal Government quality measures

The Australian Federal Government has established two quality systems for assessing university performance. These are the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) and Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA).

The TEQSA reviews of universities essentially look at processes, procedures and their documentation. The TEQSA exercise, largely bureaucratic rather than strategic, is currently moving towards its second round of assessments, with all Australian universities having seemingly received mixed (but generally positive) results in the first round. TEQSA's shortcoming is that it does not specifically address issues of governance or strategic planning in anything other than a bureaucratic sense. In the April 2007 edition of Campus Review,[34] the Vice Chancellor of the University of New South Wales, Fred Hilmer, criticised both AUQA (the agency before it became TEQSA) and the Research Quality Framework (a precursor to the ERA that was discarded before rollout):

"... singling out AUQA, Hilmer notes that while complex quality processes are in place, not one institution has lost its accreditation – 'there's never been a consequence – so it's just red tape...'"

"...The RQF is not a good thing – it's an expensive way to measure something that could be measured relatively simply. If we wanted to add impacts as one of the factors, then let's add impact. That can be achieved simply without having to go through what looks like a $90 million dollar exercise with huge implementation issues."

The RQF (scrapped with the change in government in 2007) was modelled on the British Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) system, and was intended to assess the quality and impact of research undertaken at universities through panel-based evaluation of individual research groups within university disciplines. Its objective was to provide government, industry, business and the wider community with an assurance that research quality within Australian universities had been rigorously assessed against international standards. Assessment was expected to allow research groups to be benchmarked against national and international standards across discipline areas. If successfully implemented, this would have been a departure from the Australian Government's traditional approach to measuring research performance exclusively through bibliometrics. The RQF was fraught with controversy, particularly because the cost of such an undertaking (using international panels) and the difficulty in having agreed definitions of research quality and impact. The Labor government which scrapped the RQF has yet to outline any system which will replace it, stating however that it will enter into discussions with higher education providers, to gain consensus on a streamlined, metrics-driven approach.

International reputations

Australian universities consistently feature well in the top 150 international universities as ranked by the Academic Ranking of World Universities, the QS World University Rankings, and the Times Higher Education World University Rankings. From 2012 through 2016, eight Australian universities have featured in the top 150 universities of these three lists.[35][36][37][38] The eight universities which are regularly ranked highly are Australian National University, the University of Melbourne, the University of Queensland, the University of Adelaide, Monash University, the University of Western Australia, the University of New South Wales, and the University of Sydney. These universities comprise Australia's Group of Eight, a coalition of research-intensive Australian universities.[39]

See also

References

- "Overview". Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. Archived from the original on 6 September 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- "Universities and Higher Education – Study in Australia". Australian Government.

- "Higher education qualifications".

- "Subscribe to the Australian | Newspaper home delivery, website, iPad, iPhone & Android apps".

- Agency, Tertiary Education Quality and Standards (6 October 2017). "What we do". www.teqsa.gov.au. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Norton, Andrew; Cherastidtham, Ittima (11 August 2019), Risks and rewards: when is vocational education a good alternative to higher education?, Grattan Institute, retrieved 14 August 2019

- http://training.gov.au/Training/Details/TAE40110

- Breen, Jim (December 2002). "Higher Education in Australia: Structure, Policy & Debate". Monash University.

- "The White Hat Guide to Australian Nobel Prize Winners". White Hat. 1 January 2014. Archived from the original on 14 December 2004. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- Maslen, Geoff (6 April 2018). "Momentous university open door policy abandoned". University World News. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

But critics within and outside the universities began complaining about the lower educational standards of new students. They pointed out that an increasing number of school-leavers were being admitted, including those with low school scores in their examinations. Thousands of students who, in the past, would have failed to gain entry, were enrolling and finding an academic life increasingly difficult.

- Duffy, national education reporter Conor (12 April 2020). "Relief for universities will 'unashamedly' prioritise domestic students". ABC News. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Centre, Ministers' Media (12 April 2020). "Higher Education Relief Package". Ministers' Media Centre. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/property/booming-student-market-a-valuable-property/news-story/6bb3823260aa3443f0c26909406d089b

- https://www.macrobusiness.com.au/2019/11/australian-universities-double-down-on-international-students/

- https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-07-27/temporary-graduate-visa-485-boom/10035390

- "International student numbers hit new high". 21 February 2017.

- "Most international students come to Australia from these countries".

- "International students "dumbing down academic standards"". Macrobusiness. Macro Associates PTY LTD. 13 November 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

Universities have eroded both entry and teaching standards to entice huge volumes of lower-quality, full fee-paying international students

- "International student graduates flood low-skilled jobs". Macrobusiness. Macro Associates PTY LTD. 2 October 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

The answer for why this situation has been allowed to persist is simple; to funnel as many international students through Australia’s universities as possible in order to maximise fees.

- Foster, Gigi (20 April 2015). "The slide of academic standards in Australia: A cautionary tale". The Conversation. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Lane, Bernard (4 October 2017). "'The pressure of inclusion has diminished the quality of higher education': Frank Furedi". The Australian. News Limited. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- Karmel, Tom; Carroll, David (14 October 2016), Has the Graduate Job Market Been Swamped? (PDF), National Institute of Labour Studies, Flinders University

- Shifting the Dial: 5-Year Productivity Review (PDF). Inquiry Report 84. Canberra: Productivity Commission. 3 August 2017. p. 102. ISBN 9781740376235.

- Redican, Brian (21 November 2017). "Why university degree explosion is keeping wages growth low". Financial Review. Fairfax. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

With so many highly qualified graduates after the same job, employers have less incentive to compete by offering higher starting salaries. Those graduates who miss out on the best jobs will find work, but this might be a teaching graduate working in a childcare centre, or a law graduate driving an Uber.

- Whiteley, Sonia (October 2017). "2017 Graduate Outcomes Survey – Longitudinal" (PDF). Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching. Department of Education and Training. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Moore, Shane (24 October 2019). "How Much Do Tradies Really Earn?". Trade Risk. Trade Risk Insurance Pty Ltd. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

We are using the taxable incomes provided to us by thousands of self-employed tradies from around Australia.

- Norton, Andrew; Cherastidtham, Ittima (16 September 2018), Mapping Australian higher education 2018, Grattan Institute, retrieved 16 September 2018

- http://www.chiefscientist.gov.au/2015/10/new-report-boosting-high-impact-entrepreneurship-in-australia/

- https://docs.education.gov.au/node/43231

- Marginson, S. National system reform in global context: The case of Australia Archived 18 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Reforms and consequences in higher education system: An international symposium, National Centre of Sciences, Hitotubashi Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, 2009.

- Marginson, Simon (2000). "Rethinking Academic Work in the Global Era". Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management. 22: 23–35. doi:10.1080/713678133.

- Singhal, Pallavi (21 June 2019). "University vice-chancellor salaries soaring past $1.5 million - and set to keep going". The Age. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

The top vice-chancellors are making three times as much as the prime minister.

- Cain, John; Hewitt, John (2004), Off course: From public place to marketplace at Melbourne University, Scribe

- Campus Review

- Dodd, Tim (16 August 2014). "Sydney Uni drops out of top 100; Melbourne Uni rises". Financial Review. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2016". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "QS World University Rankings". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Top Universities in Australia 2017". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Williams, R; Van Dyke, N (2007). "Measuring the international standing of universities with an application to Australian universities". Higher Education. 53 (6): 819–841. doi:10.1007/s10734-005-7516-4.

.jpg.webp)