The Bulletin (Australian periodical)

The Bulletin was an Australian magazine first published in Sydney on 31 January 1880. The publication's focus was politics and business, with some literary content, and editions were often accompanied by cartoons and other illustrations. The views promoted by the magazine varied across different editors and owners, with the publication consequently considered either on the left or right of the political spectrum at various stages in its history. The Bulletin was highly influential in Australian culture and politics until after the First World War, and was then noted for its nationalist, pro-labour, and pro-republican writing. It was revived as a modern news magazine in the 1960s as The Bulletin with Newsweek, and was Australia's longest running magazine publication until the final issue was published in January 2008.[1]

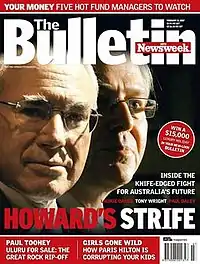

Front cover of the 13 February 2007 edition | |

| Editor-in-Chief | John Lehmann |

|---|---|

| Categories | News magazine |

| Frequency | Weekly |

| Year founded | 1880 |

| Final issue | January 2008 |

| Company | Australian Consolidated Press |

| Country | Australia |

| Based in | Sydney |

| Language | English |

| ISSN | 1440-7485 |

Early history

The Bulletin was founded by J. F. Archibald and John Haynes, with the first issue being published in 1880.[2] The original content of The Bulletin consisted of a mix of political comment, sensationalised news, and Australian literature.[3] For a short period in 1880, their first artist William Macleod was also a partner.[4][5]

In the early years, The Bulletin played a significant role in the encouragement and circulation of nationalist sentiments that remained influential far into the next century. Its writers and cartoonists regularly attacked the British, Chinese, Japanese, Indians, Jews, and Aborigines.[6] In 1886, editor James Edmond changed The Bulletin's nationalist banner from "Australia for Australians" to "Australia for the White Man".[3] An editorial, published in The Bulletin the following year, laid out its reasons for choosing such banners:[7]

By the term Australian we mean not those who have been merely born in Australia. All white men who come to these shores—with a clean record—and who leave behind them the memory of the class distinctions and the religious differences of the old world ... all men who leave the tyrant-ridden lands of Europe for freedom of speech and right of personal liberty are Australians before they set foot on the ship which brings them hither. Those who ... leave their fatherland because they cannot swallow the worm-eaten lie of the divine right of kings to murder peasants, are Australian by instinct—Australian and Republican are synonymous.

As The Bulletin evolved, it became known as a platform for young and aspiring writers to showcase their short stories and poems to large audiences. By 1890, it was the focal point of an emerging literary nationalism known as the "Bulletin School", and a number of its contributors, often called bush poets, have become giants of Australian literature. Notable writers associated with The Bulletin at this time include:

A number of notable artists provided illustrations and cartoons for the publication. These include,

|

|

|

According to The Times of London, "It was The Bulletin that educated Australia up to Federation".[9]

In his 1923 novel Kangaroo, English author D. H. Lawrence wrote of a character who reads The Bulletin and appreciates its straightforwardness and the "kick" in its writing: "It beat no solemn drums. It had no deadly earnestness. It was just stoical and spitefully humorous."[10] In The Australian Language (1946), Sidney Baker wrote: "Perhaps never again will so much of the true nature of a country be caught up in the pages of a single journal". The Bulletin continued to support the creation of a distinctive Australian literature into the 20th century, most notably under the editorship of Samuel Prior (1915–1933), who created the first novel competition.[3]

The publication was folio size and initially consisted of eight pages, increasing to 12 pages in July 1880, and had reached 48 pages by 1899. The first issue sold for four pence, later reduced to three pence, and then, in 1883, was increased to six pence.[11]

Later era

The literary character of The Bulletin continued until 1961, when it was brought by Australian Consolidated Press (ACP), merged with the Observer (another ACP publication), and shifted to a news magazine format.[3] Donald Horne was appointed as chief editor and quickly removed "Australia for the White Man" from the banner. The magazine was costing ACP more than it made, but they accepted that price "for the prestige of publishing Australia's oldest magazine".[6] Kerry Packer, in particular, had a personal liking for the magazine and was determined to keep it alive.[12]

In 1974, as a result of its publication of a leaked Australian Security Intelligence Organisation paper discussing Deputy Prime Minister Jim Cairns, the Whitlam Government called the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security.[13]

In the 1980s and 1990s, The Bulletin's "ageing subscribers were not being replaced and its newsstand visibility had dwindled".[12] Trevor Kennedy convinced publisher Richard Walsh to return to the magazine. Walsh promoted Lyndall Crisp to be its first female editor, but James Packer then advocated that former 60 Minutes executive producer Gerald Stone be made editor-in-chief. Later, in December 2002, Kerry Packer anointed Garry Linnell as editor-in-chief.

Kerry Packer died in 2005, and in 2007 James Packer sold controlling interest in the Packer media assets (PBL Media) to the private equity firm CVC Asia Pacific.[12] On 24 January 2008, ACP Magazines announced that it was shutting The Bulletin. Circulation had declined from its 1990s' levels of over 100,000 down to 57,000,[6] which has been attributed in part to readers preferring the internet as their source for news and current affairs.[14]

Editors

The Bulletin had many editors over its time in print, and these are listed below:

- J. F. Archibald

- John Haynes

- William Henry Traill[15]

- James Edmond

- Samuel Prior[16]

- John E. Webb[17]

- David Adams

- Donald Horne

- Peter Hastings[18]

- Peter Coleman

- Trevor Kennedy

- James Hall[19]

- Lyndall Crisp[20]

- Gerald Stone

- Max Walsh

- David Dale

- Paul Bailey[21]

- Garry Linnell[22]

- Kathy Bail[23]

- John Lehmann[24]

S. H. Prior

Samuel Henry Prior (10 January 1869 – 6 June 1933) was an Australian journalist and editor, best known for his editorship and ownership of The Bulletin.[16] Born in Brighton, South Australia, Prior was educated at Glenelg Grammar School and the Bendigo School of Mines and Industries. He started his career as a teacher, before becoming a mining reporter at the Bendigo Independent. In 1887, he was assigned to Broken Hill, New South Wales, to report on the silver mine.[25][16] He was briefly editor at the Broken Hill Times and then at its successor, Broken Hill Argus. In 1889, Prior joined the Barrier Miner as editor, remaining in the role for 14 years,[25] during which time he displayed nationalism and championed trade unionism and the Federation of Australia.[16]

After sending some of his work to J. F. Archibald at the Sydney Bulletin, he was appointed finance editor in 1903.[16] In this role, he increased importance of the "Wild Cat" column, a financial and investment news and insights column focused on mining companies, which eventually (by 1923) grew into Wild Cat Monthly. Prior was promoted to associate editor in 1912. In 1914, Archibald sold his shares in The Bulletin to Prior, making Prior the majority shareholder. In 1915, he became the senior editor, in which position he built The Bulletin's reputation for literature and for financial journalism.[16] In 1927, he was sold the remaining shares in The Bulletin and thus became not only its editor but its sole owner and manager. In 1928, he inaugurated the first Bulletin Novel Competition, offering aspiring writers prize money and the publishing of their work in The Bulletin.

Prior remained editor until 1933, when he died from heart disease. In 1935, his son established the S. H. Prior Memorial Prize for a work of Australian literature. Prior's family retained control of the magazine until it was bought by Consolidated Press Ltd in 1960.[16]

Garry Linnell

Garry Linnell joined The Bulletin in 2001 and became editor-in-chief in 2002, when the magazine was already dropping in circulation and running at a loss. On one occasion, Kerry Packer called Linnell to his office, and, when Linnell asked what Packer wanted for The Bulletin, Packer said: "Son, just make 'em talk about it."[26] When former Prime Minister Paul Keating sent Linnell a letter criticising the magazine and calling it "rivettingly mediocre", Linnell published the letter in the magazine, promoted that "Paul Keating Writes for Us", and awarded Keating with "Letter of the Week", with the prize for that being a year's subscription to the magazine.[27] In 2005, Linnell offered a $1.25-million reward to anyone who found an extinct Tasmanian tiger.[12]

Columnists and bloggers

Regular columnists and bloggers on the magazine's website included:

- Patrick Cook

- Paul Daley[28]

- Julie-Anne Davies[29]

- Roy Eccleston[30]

- Ellen Fanning

- Katherine Fleming[31]

- Chris Hammer[32]

- Laurie Oakes

- Leo Schofield

- Adam Shand

- Terrey Shaw

- Rebecca Urban[33]

References

- Jesse Hogan (24 January 2008). "The Bulletin shuts down". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- Bridget Griffen-Foley (2004). "From Tit-Bits to Big Brother: a century of audience participation in the media" (PDF). Media, Culture & Society. 26 (4). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- "The Bulletin". AustLit.

- "Mr. William MACLEOD". The Herald (16, 255). Victoria, Australia. 24 June 1929. p. 4. Retrieved 24 February 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Death of Mr. William MACLEOD". The Sydney Morning Herald (28, 540). New South Wales, Australia. 25 June 1929. p. 12. Retrieved 24 February 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- Thompson, Stephen (January 2013). "1910 The Bulletin Magazine". Migration Heritage Centre NSW. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- The Bulletin, 2 July 1887

- Jill, Roe (1990). "Wildman, Alexina Maude (Ina) (1867–1896)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 12. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 27 November 2018 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- The Times, 31 August 1903, quoted in, Murray-Smith, Stephen (1987), The dictionary of Australian quotations, Melbourne, Heinemann, p.267. ISBN 0855610697

- Lawrence, D. H. (1923). "Chapter 14. Bits.". Kangaroo. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- Stuart, Lurline (1979) Nineteenth century Australian periodicals: an annotated bibliography, Sydney, Hale & Iremonger, p.52. ISBN 0908094531

- Haigh, Gideon (1 March 2008). "Packed It In: The Demise of The Bulletin". The Monthly.

- Coventry, CJ. Origins of the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security (2018: MA thesis submitted at UNSW).

- Steffen, Miriam (24 January 2008). "End of an era as The Bulletin closes". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- B. G. Andrews, "Traill, William Henry (1843–1902)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1976, Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- Peter Kirkpatrick, "Prior, Samuel Henry (1869–1933)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1988, accessed online 21 April 2015.

- "John E. Webb". AustLit.

- Gavin Souter, "Hastings, Peter Dunstan (1920–1990)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 2007, Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- "James Hall". AustLit.

- "Crisp, Lyndall", Trove, 2009, retrieved 21 April 2015

- "Paul Bailey". AustLit.

- "Garry Linnell". AustLit.

- "Kathy Bail". AustLit.

- "John Lehmann". AustLit.

- "S. H. Prior". AustLit.

- Knott, Matthew (3 July 2013). "The man to save Fairfax? The unstoppable rise of Garry Linnell". Crikey. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- Lyons, John (25 January 2008). "Foreign buyers silence The Bulletin". News. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- Thebulletinblog.com.au

- Thebulletinblog.com.au

- Thebulletinblog.com.au

- Thebulletinblog.com.au Archived 15 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Thebuletinblog.com.au

- Thebulletinblog.com.au

Further reading

- Bruce Bennett; et al. (1998). The Oxford literary History of Australia. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-553737-6.

- Clay Djubal (2017). "Looking in All the Wrong Places;" Or, Harlequin False Testimony and the Bulletin Magazine's Mythical Construction of National Identity, Theatrical Enterprise and the Social World of Little Australia, circa 1880-1920". Mixed Bag: Early Australian Variety Theatre and Popular Culture Monograph Series. 3 (21 Sept. 2017). Have Gravity Will Threaten. ISSN 1839-5511.

- Dutton, Geoffrey (1964). The Literature of Australia. Melbourne: Penguin.

- Vance Palmer (1980). The Legend of the Nineties. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-83690-5.

- Patricia Rolfe (1979). The Journalistic Javelin: An Illustrated History of the Bulletin. Sydney: Wildcat Press. ISBN 978-0-908463-02-2.

- William Wilde; et al. (1985). The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554233-9.

External links

- Garry Wotherspoon (2010). "The Bulletin". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 2 October 2015. [CC-By-SA]