The China Syndrome

The China Syndrome is a 1979 American drama neo-noir thriller film directed by James Bridges and written by Bridges, Mike Gray, and T. S. Cook. The film stars Jane Fonda, Jack Lemmon, Michael Douglas (who also produced), Scott Brady, James Hampton, Peter Donat, Richard Herd, and Wilford Brimley. It follows a television reporter and her cameraman who discover safety coverups at a nuclear power plant. "China syndrome" is a fanciful term that describes a fictional result of a nuclear meltdown, where reactor components melt through their containment structures and into the underlying earth, "all the way to China".

| The China Syndrome | |

|---|---|

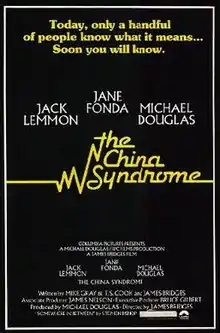

Promotional poster | |

| Directed by | James Bridges |

| Produced by | Michael Douglas |

| Written by | |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Stephen Bishop |

| Cinematography | James Crabe |

| Edited by | David Rawlins |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 122 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5.9 million[1] |

| Box office | $51.7 million[2] |

The China Syndrome premiered at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival, where it competed for the Palme d'Or while Lemmon received the Best Actor Prize.[3] It was theatrically released on March 16, 1979, twelve days before the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, which gave the film's subject matter an unexpected prescience. It became a critical and commercial success. Reviewers praised the film's screenplay, direction, and performances (most notably of Fonda and Lemmon), while it grossed $51.7 million on a production budget of $5.9 million. The film received four nominations at the 52nd Academy Awards; Best Actor (for Lemmon), Best Actress (for Fonda), Best Original Screenplay, and Best Production Design.[4]

Plot

While visiting the (fictional) Ventana nuclear power plant outside Los Angeles, television news reporter Kimberly Wells, her cameraman Richard Adams and their soundman Hector Salas witness the plant going through a turbine trip and corresponding SCRAM (emergency shutdown). Shift Supervisor Jack Godell notices an unusual vibration in his cup of coffee.

In response to a gauge indicating high water levels, Godell begins removing water from the core, but the gauge remains high as operators open more valves to dump water. Another operator notices a second gauge indicating low water levels. Godell taps the first gauge, which immediately unsticks and drops to indicate very low levels. The crew urgently pump water back in and celebrate in relief at bringing the reactor back under control.[lower-alpha 1]

Richard has surreptitiously filmed the incident, despite being asked not to film for security reasons. Kimberly's superior refuses her report of what happened. Richard steals the footage and shows it to experts who conclude that the plant came perilously close to meltdown – the China syndrome.

During an inspection of the plant before it is brought back online, Godell discovers a puddle of radioactive water that has apparently leaked from a pump. He pushes to delay restarting the plant, but the plant superintendent wants nothing standing in the way of the restart.

Godell finds that a series of radiographs supposedly verifying the welds on the leaking pump are identical – the contractor simply kept resubmitting the same picture. He brings the evidence to the plant manager, who brushes him off as paranoid, stating that new radiographs would cost $20 million. Godell confronts Royce, an employee of Foster-Sullivan who built the plant, as it was he who signed off on the radiographs. Godell threatens to go to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, but Royce threatens him; later, a pair of men from Foster-Sullivan park outside his house.

Kimberly and Richard confront Godell at his home and he voices his concerns. Kimberly and Richard ask him to testify at the NRC hearings over Foster-Sullivan's plans to build another nuclear plant. Godell agrees to obtain, through Hector, the false radiographs to take to the hearings.

Hector's car is run off the road and the radiographs are taken from him. Godell is chased by the men waiting outside his home. He takes refuge inside the plant, where he finds that the reactor is being brought up to full power. Grabbing a gun from a security guard, he forces everyone out, including his friend and co-worker Ted Spindler, and demands to be interviewed by Kimberly on live television. Plant management agrees to the interview in order to buy time as they try to regain control of the plant.

Minutes into the broadcast, plant technicians deliberately cause a SCRAM so they can distract Godell and retake the control room. A SWAT team forces its way in, the television cable is cut, and Godell is shot. Before dying, he feels the unusual vibration again. The resulting SCRAM is brought under control only by the plant's automatic systems, and the plant suffers significant damage as the pump malfunctions.

Plant officials try to paint Godell as emotionally disturbed, but are contradicted by a distraught Spindler on live television saying Godell was not crazy and would never have taken such drastic steps had there not been something wrong. A tearful Kimberly concludes her report and the news cuts to commercial.

Cast

- Jane Fonda as Kimberly Wells

- Jack Lemmon as Jack Godell

- Michael Douglas as Richard Adams

- Scott Brady as Herman DeYoung

- Wilford Brimley as Ted Spindler

- James Hampton as Bill Gibson

- Peter Donat as Don Jacovich

- Richard Herd as Evan McCormack

- Daniel Valdez as Hector Salas

- Stan Bohrman as Pete Martin

- James Karen as Mac Churchill

Reception

Roger Ebert reviewed it as:

...a terrific thriller that incidentally raises the most unsettling questions about how safe nuclear power plants really are. ... The movie is ... well-acted, well-crafted, scary as hell. The events leading up to the "accident" in The China Syndrome are indeed based on actual occurrences at nuclear plants. Even the most unlikely mishap (a stuck needle on a graph causing engineers to misread a crucial water level) really happened at the Dresden plant outside Chicago. And yet the movie works so well not because of its factual basis, but because of its human content. The performances are so good, so consistently, that The China Syndrome becomes a thriller dealing in personal values.[5]

Movie Reviews UK noted the film is:

so accurate that, even though they're fictional, they could easily be documentaries...we see the greatest fears of the NIMBY culture unearthed when a nuclear power station almost goes out of control and the men-in-suits cover it up...[unknown] to them, the entire incident is covertly filmed by a visiting TV news-crew.

The acting is also credited:

The power of this film is more than just the acting, although Lemmon is superb, and more than just the script. It is that this scenario could really happen...atmosphere produced in the plants' control-room is heart-stoppingly intense; characters are uniformly well-acted. I recommend The China Syndrome to everyone as an example of the dangers of money and corruption.[6]

John Simon said The China Syndrome was a taut, intelligent, and chillingly gripping thriller till it turns melodramatic at its end. He called the ending both false and bathetic.[7]

The film has a rating of 86% on Rotten Tomatoes based on reviews from 35 critics. The critical consensus reads: "With gripping themes and a stellar cast, The China Syndrome is the rare thriller that's as thought-provoking as it is tense".[8] On Metacritic it has a score of 81% based on reviewsfrom 16 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[9]

Box office

The film opened in 534 theatres in the United States and grossed $4,354,854 in its opening weekend.[10]

Response of nuclear industry

The March 1979 release was met with backlash from the nuclear power industry's claims of it being "sheer fiction" and a "character assassination of an entire industry".[11] Twelve days later, the Three Mile Island nuclear accident occurred in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. While some credit the accident's timing in helping to sell tickets,[12] the studio attempted to avoid appearing as if they were exploiting the accident, which included pulling the film from some theaters.[13]

Accolades

Notes

- The sequence of events in the movie is based on events that occurred in 1970 at the Dresden Generating Station outside Chicago. In that case, the indicator stuck low and the operators responded by adding ever-more water.

- Tied with Dustin Hoffman for Kramer vs. Kramer.

References

- "The China Syndrome". Sunnycv.com. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- "Box Office Information for The China Syndrome". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- "Festival de Cannes: The China Syndrome". Festival-cannes.com. Retrieved May 24, 2009.

- "The China Syndrome (1979): Awards". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1979). "The China Syndrome Movie Review (1979)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- "The China Syndrome (1979)". Film.u-net.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- Simon, John (1982). Reverse Angle. Crown Publishers Inc. p. 377.

- "The China Syndrome". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- "The China Syndrome". Metacritic.

- Pollock, Dale (June 20, 1979). "UA Puts Four-Day 'Rocky II' B. O. At $8.1 Million". Daily Variety. p. 1.

- Nuclear Experts Debate ‘The China Syndrome’ David Burnham The New York Times March 18, 1979

- "The China Syndrome: Special Edition". Dvdverdict.com. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- Movies That Shook the World, American Movie Classics 2006.

- "The 52nd Academy Awards". Oscars. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- "Film in 1980". BAFTA. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- "The China Syndrome". Festival De Cannes. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- "32nd Annual DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- "Winners & Nominees: China Syndrome, The". Golden Globes. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- "1979 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- "Writers Guild Award Winners 1995–1949". Writers Guild Awards. Retrieved February 21, 2019.