Nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions that release nuclear energy to generate heat, which most frequently is then used in steam turbines to produce electricity in a nuclear power plant. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced by nuclear fission of uranium and plutonium. Nuclear decay processes are used in niche applications such as radioisotope thermoelectric generators in some space probes such as Voyager 2. Generating electricity from fusion power remains at the focus of international research. This article mostly deals with nuclear fission power for electricity generation.

%252C_USS_Long_Beach_(CGN-9)_and_USS_Bainbridge_(DLGN-25)_underway_in_the_Mediterranean_Sea_during_Operation_Sea_Orbit%252C_in_1964.jpg.webp)

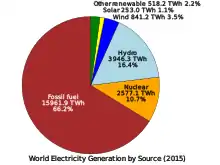

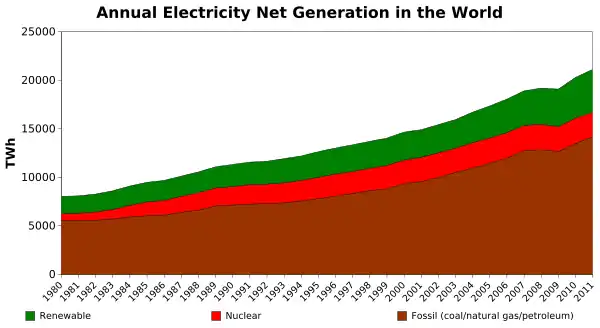

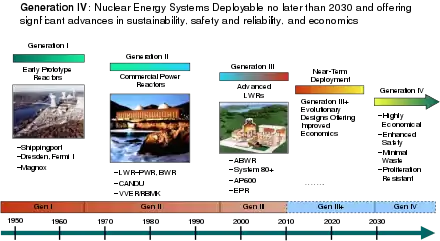

Civilian nuclear power supplied 2,586 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity in 2019, equivalent to about 10% of global electricity generation, and was the second largest low-carbon power source after hydroelectricity.[5][6] As of December 2020, there are 441 civilian fission reactors in the world, with a combined electrical capacity of 392 gigawatt (GW). There are also 54 nuclear power reactors under construction and 98 reactors planned, with a combined capacity of 60 GW and 103 GW, respectively.[7] The United States has the largest fleet of nuclear reactors, generating over 800 TWh zero-emissions electricity per year with an average capacity factor of 92%.[8] Most reactors under construction are generation III reactors in Asia.[9]

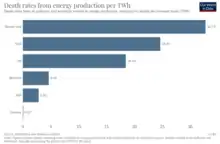

Nuclear power has one of the lowest levels of fatalities per unit of energy generated compared to other energy sources. Coal, petroleum, natural gas and hydroelectricity each have caused more fatalities per unit of energy due to air pollution and accidents.[10] Since its commercialization in the 1970s, nuclear power has prevented about 1.84 million air pollution-related deaths and the emission of about 64 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent that would have otherwise resulted from the burning of fossil fuels.[11]

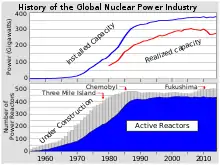

Accidents in nuclear power plants include the Chernobyl disaster in the Soviet Union in 1986, the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan in 2011, and the more contained Three Mile Island accident in the United States in 1979.

There is a debate about nuclear power. Proponents, such as the World Nuclear Association and Environmentalists for Nuclear Energy, contend that nuclear power is a safe, sustainable energy source that reduces carbon emissions. Nuclear power opponents, such as Greenpeace and NIRS, contend that nuclear power poses many threats to people and the environment.

History

Origins

In 1932, physicist Ernest Rutherford discovered that when lithium atoms were "split" by protons from a proton accelerator, immense amounts of energy were released in accordance with the principle of mass–energy equivalence. However, he and other nuclear physics pioneers Niels Bohr and Albert Einstein believed harnessing the power of the atom for practical purposes anytime in the near future was unlikely.[12] The same year, Rutherford's doctoral student James Chadwick discovered the neutron.[13] Experiments bombarding materials with neutrons led Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie to discover induced radioactivity in 1934, which allowed the creation of radium-like elements.[14] Further work by Enrico Fermi in the 1930s focused on using slow neutrons to increase the effectiveness of induced radioactivity. Experiments bombarding uranium with neutrons led Fermi to believe he had created a new transuranic element, which was dubbed hesperium.[15]

In 1938, German chemists Otto Hahn[16] and Fritz Strassmann, along with Austrian physicist Lise Meitner[17] and Meitner's nephew, Otto Robert Frisch,[18] conducted experiments with the products of neutron-bombarded uranium, as a means of further investigating Fermi's claims. They determined that the relatively tiny neutron split the nucleus of the massive uranium atoms into two roughly equal pieces, contradicting Fermi.[15] This was an extremely surprising result; all other forms of nuclear decay involved only small changes to the mass of the nucleus, whereas this process—dubbed "fission" as a reference to biology—involved a complete rupture of the nucleus. Numerous scientists, including Leó Szilárd, who was one of the first, recognized that if fission reactions released additional neutrons, a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction could result.[19][20] Once this was experimentally confirmed and announced by Frédéric Joliot-Curie in 1939, scientists in many countries (including the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and the Soviet Union) petitioned their governments for support of nuclear fission research, just on the cusp of World War II, for the development of a nuclear weapon.[21]

First nuclear reactor

In the United States, where Fermi and Szilárd had both emigrated, the discovery of the nuclear chain reaction led to the creation of the first man-made reactor, the research reactor known as Chicago Pile-1, which achieved criticality on December 2, 1942. The reactor's development was part of the Manhattan Project, the Allied effort to create atomic bombs during World War II. It led to the building of larger single-purpose production reactors, such as the X-10 Pile, for the production of weapons-grade plutonium for use in the first nuclear weapons. The United States tested the first nuclear weapon in July 1945, the Trinity test, with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki taking place one month later.

In August 1945, the first widely distributed account of nuclear energy, the pocketbook The Atomic Age, was released. It discussed the peaceful future uses of nuclear energy and depicted a future where fossil fuels would go unused. Nobel laureate Glenn Seaborg, who later chaired the United States Atomic Energy Commission, is quoted as saying "there will be nuclear powered earth-to-moon shuttles, nuclear powered artificial hearts, plutonium heated swimming pools for SCUBA divers, and much more".[24]

In the same month, with the end of the war, Seaborg and others would file hundreds of initially classified patents,[20] most notably Eugene Wigner and Alvin Weinberg's Patent #2,736,696, on a conceptual light water reactor (LWR) that would later become the United States' primary reactor for naval propulsion and later take up the greatest share of the commercial fission-electric landscape.[25]

The United Kingdom, Canada,[26] and the USSR proceeded to research and develop nuclear energy over the course of the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Electricity was generated for the first time by a nuclear reactor on December 20, 1951, at the EBR-I experimental station near Arco, Idaho, which initially produced about 100 kW.[27][28] In 1953, American President Dwight Eisenhower gave his "Atoms for Peace" speech at the United Nations, emphasizing the need to develop "peaceful" uses of nuclear power quickly. This was followed by the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 which allowed rapid declassification of U.S. reactor technology and encouraged development by the private sector.

Early years

The first organization to develop nuclear power was the U.S. Navy, with the S1W reactor for the purpose of propelling submarines and aircraft carriers. The first nuclear-powered submarine, USS Nautilus, was put to sea in January 1954.[30][31] The trajectory of civil reactor design was heavily influenced by Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, who with Weinberg as a close advisor, selected the PWR/Pressurized Water Reactor design, in the form of a 10 MW reactor for the Nautilus, a decision that would result in the PWR receiving a government commitment to develop, an engineering lead that would result in a lasting impact on the civilian electricity market in the years to come.[32] The United States Navy Nuclear Propulsion design and operation community, under Rickover's style of attentive management retains a continuing record of zero reactor accidents (defined as the uncontrolled release of fission products to the environment resulting from damage to a reactor core).[33][34] with the U.S. Navy fleet of nuclear-powered ships, standing at some 80 vessels as of 2018.

On June 27, 1954, the USSR's Obninsk Nuclear Power Plant, based on what would become the prototype of the RBMK reactor design, became the world's first nuclear power plant to generate electricity for a power grid, producing around 5 megawatts of electric power.[36]

On July 17, 1955, the BORAX III reactor, the prototype to later Boiling Water Reactors, became the first to generate electricity for an entire community, the town of Arco, Idaho.[37] A motion picture record of the demonstration, of supplying some 2 megawatts (2 MW) of electricity, was presented to the United Nations,[38] Where at the "First Geneva Conference", the world's largest gathering of scientists and engineers, met to explore the technology in that year. In 1957 EURATOM was launched alongside the European Economic Community (the latter is now the European Union). The same year also saw the launch of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

.jpg.webp)

The world's first "commercial nuclear power station", Calder Hall at Windscale, England, was opened in 1956 with an initial capacity of 50 MW per reactor (200 MW total),[43][44] it was the first of a fleet of dual-purpose MAGNOX reactors, though officially code-named PIPPA (Pressurized Pile Producing Power and Plutonium) by the UKAEA to denote the plant's dual commercial and military role.[45]

The U.S. Army Nuclear Power Program formally commenced in 1954. Under its management, the 2 megawatt SM-1, at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, was the first in the United States to supply electricity in an industrial capacity to the commercial grid (VEPCO), in April 1957.[46]

The first commercial nuclear station to become operational in the United States was the 60 MW Shippingport Reactor (Pennsylvania), in December 1957.[47]

The 3 MW SL-1 was a U.S. Army experimental nuclear power reactor at the National Reactor Testing Station, Idaho National Laboratory. It was derived from the Borax Boiling water reactor (BWR) design and it first achieved operational criticality and connection to the grid in 1958. For reasons unknown, in 1961 a technician removed a control rod about 22 inches farther than the prescribed 4 inches. This resulted in a steam explosion which killed the three crew members and caused a meltdown.[48][49] The event was eventually rated at 4 on the seven-level INES scale.

In service from 1963 and operated as the experimental testbed for the later Alfa-class submarine fleet, one of the two liquid-metal-cooled reactors on board the Soviet submarine K-27, underwent a fuel element failure accident in 1968, with the emission of gaseous fission products into the surrounding air, producing 9 crew fatalities and 83 injuries.[50]

Development and early opposition to nuclear power

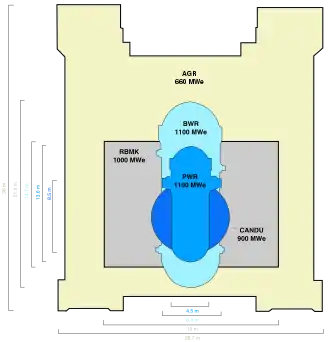

- PWR: 277 (63.2%)

- BWR: 80 (18.3%)

- GCR: 15 (3.4%)

- PHWR: 49 (11.2%)

- LWGR: 15 (3.4%)

- FBR: 2 (0.5%)

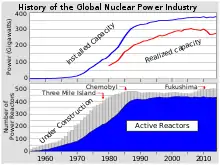

The total global installed nuclear capacity initially rose relatively quickly, rising from less than 1 gigawatt (GW) in 1960 to 100 GW in the late 1970s, and 300 GW in the late 1980s. Since the late 1980s worldwide capacity has risen much more slowly, reaching 366 GW in 2005. Between around 1970 and 1990, more than 50 GW of capacity was under construction (peaking at over 150 GW in the late 1970s and early 1980s)—in 2005, around 25 GW of new capacity was planned. More than two-thirds of all nuclear plants ordered after January 1970 were eventually cancelled.[30] A total of 63 nuclear units were canceled in the United States between 1975 and 1980.[52]

In 1972 Alvin Weinberg, co-inventor of the light water reactor design (the most common nuclear reactors today) was fired from his job at Oak Ridge National Laboratory by the Nixon administration, "at least in part" over his raising of concerns about the safety and wisdom of ever larger scaling-up of his design, especially above a power rating of ~500 MWe, as in a loss of coolant accident scenario, the decay heat generated from such large compact solid-fuel cores was thought to be beyond the capabilities of passive/natural convection cooling to prevent a rapid fuel rod melt-down and resulting in then, potential far reaching fission product pluming. While considering the LWR, well suited at sea for the submarine and naval fleet, Weinberg did not show complete support for its use by utilities on land at the power output that they were interested in for supply scale reasons, and would request for a greater share of AEC research funding to evolve his team's demonstrated,[53] Molten-Salt Reactor Experiment, a design with greater inherent safety in this scenario and with that an envisioned greater economic growth potential in the market of large-scale civilian electricity generation.[54][55][56]

Similar to the earlier BORAX reactor safety experiments, conducted by Argonne National Laboratory,[57] in 1976 Idaho National Laboratory began a test program focused on LWR reactors under various accident scenarios, with the aim of understanding the event progression and mitigating steps necessary to respond to a failure of one or more of the disparate systems, with much of the redundant back-up safety equipment and nuclear regulations drawing from these series of destructive testing investigations.[58]

During the 1970s and 1980s rising economic costs (related to extended construction times largely due to regulatory changes and pressure-group litigation)[59] and falling fossil fuel prices made nuclear power plants then under construction less attractive. In the 1980s in the U.S. and 1990s in Europe, the flat electric grid growth and electricity liberalization also made the addition of large new baseload energy generators economically unattractive.

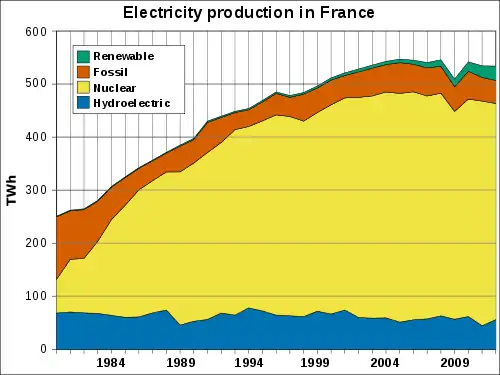

The 1973 oil crisis had a significant effect on countries, such as France and Japan, which had relied more heavily on oil for electric generation (39%[60] and 73% respectively) to invest in nuclear power.[61] The French plan, known as the Messmer plan, was for the complete independence from oil, with an envisaged construction of 80 reactors by 1985 and 170 by 2000.[62] France would construct 25 fission-electric stations, installing 56 mostly PWR design reactors over the next 15 years, though foregoing the 100 reactors initially charted in 1973, for the 1990s.[63][64] In 2019, 71% of French electricity was generated by 58 reactors, the highest percentage by any nation in the world.[65]

Some local opposition to nuclear power emerged in the U.S. in the early 1960s, beginning with the proposed Bodega Bay station in California, in 1958, which produced conflict with local citizens and by 1964 the concept was ultimately abandoned.[66] In the late 1960s some members of the scientific community began to express pointed concerns.[67] These anti-nuclear concerns related to nuclear accidents, nuclear proliferation, nuclear terrorism and radioactive waste disposal.[68] In the early 1970s, there were large protests about a proposed nuclear power plant in Wyhl, Germany. The project was cancelled in 1975 the anti-nuclear success at Wyhl inspired opposition to nuclear power in other parts of Europe and North America.[69][70] By the mid-1970s anti-nuclear activism gained a wider appeal and influence, and nuclear power began to become an issue of major public protest.[71][72] In some countries, the nuclear power conflict "reached an intensity unprecedented in the history of technology controversies".[73][74] In May 1979, an estimated 70,000 people, including then governor of California Jerry Brown, attended a march against nuclear power in Washington, D.C.[75] Anti-nuclear power groups emerged in every country that had a nuclear power programme.

Globally during the 1980s one new nuclear reactor started up every 17 days on average.[76]

Regulations, pricing and accidents

In the early 1970s, the increased public hostility to nuclear power in the United States lead the United States Atomic Energy Commission and later the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to lengthen the license procurement process, tighten engineering regulations and increase the requirements for safety equipment.[77][78] Together with relatively minor percentage increases in the total quantity of steel, piping, cabling and concrete per unit of installed nameplate capacity, the more notable changes to the regulatory open public hearing-response cycle for the granting of construction licenses, had the effect of what was once an initial 16 months for project initiation to the pouring of first concrete in 1967, escalating to 32 months in 1972 and finally 54 months in 1980, which ultimately, quadrupled the price of power reactors.[79][80]

Utility proposals in the U.S for nuclear generating stations, peaked at 52 in 1974, fell to 12 in 1976 and have never recovered,[81] in large part due to the pressure-group litigation strategy, of launching lawsuits against each proposed U.S construction proposal, keeping private utilities tied up in court for years, one of which having reached the supreme court in 1978.[82] With permission to build a nuclear station in the U.S. eventually taking longer than in any other industrial country, the spectre facing utilities of having to pay interest on large construction loans while the anti-nuclear movement used the legal system to produce delays, increasingly made the viability of financing construction, less certain.[81] By the close of the 1970s it became clear that nuclear power would not grow nearly as dramatically as once believed.

Over 120 reactor proposals in the United States were ultimately cancelled[83] and the construction of new reactors ground to a halt. A cover story in the February 11, 1985, issue of Forbes magazine commented on the overall failure of the U.S. nuclear power program, saying it "ranks as the largest managerial disaster in business history".[84]

According to some commentators, the 1979 accident at Three Mile Island (TMI) played a major part in the reduction in the number of new plant constructions in many other countries.[67] According to the NRC, TMI was the most serious accident in "U.S. commercial nuclear power plant operating history, even though it led to no deaths or injuries to plant workers or members of the nearby community."[85] The regulatory uncertainty and delays eventually resulted in an escalation of construction related debt that led to the bankruptcy of Seabrook's major utility owner, Public Service Company of New Hampshire.[86] At the time, the fourth largest bankruptcy in United States corporate history.[87]

Among American engineers, the cost increases from implementing the regulatory changes that resulted from the TMI accident were, when eventually finalized, only a few percent of total construction costs for new reactors, primarily relating to the prevention of safety systems from being turned off. With the most significant engineering result of the TMI accident, the recognition that better operator training was needed and that the existing emergency core cooling system of PWRs worked better in a real-world emergency than members of the anti-nuclear movement had routinely claimed.[77][88]

The already slowing rate of new construction along with the shutdown in the 1980s of two existing demonstration nuclear power stations in the Tennessee Valley, United States, when they couldn't economically meet the NRC's new tightened standards, shifted electricity generation to coal-fired power plants.[89] In 1977, following the first oil shock, U.S. President Jimmy Carter made a speech calling the energy crisis the "moral equivalent of war" and prominently supporting nuclear power. However, nuclear power could not compete with cheap oil and gas, particularly after public opposition and regulatory hurdles made new nuclear prohibitively expensive.[90]

In 2006 The Brookings Institution, a public policy organization, stated that new nuclear units had not been built in the United States because of soft demand for electricity, the potential cost overruns on nuclear reactors due to regulatory issues and resulting construction delays.[91]

In 1982, amongst a backdrop of ongoing protests directed at the construction of the first commercial scale breeder reactor in France, a later member of the Swiss Green Party fired five RPG-7 rocket-propelled grenades at the still under construction containment building of the Superphenix reactor. Two grenades hit and caused minor damage to the reinforced concrete outer shell. It was the first time protests reached such heights. After examination of the superficial damage, the prototype fast breeder reactor started and operated for over a decade.[92]

According to some commentators, the 1986 Chernobyl disaster played a major part in the reduction in the number of new plant constructions in many other countries:[67] Unlike the Three Mile Island accident the much more serious Chernobyl accident did not increase regulations or engineering changes affecting Western reactors; because the RBMK design, which lacks safety features such as "robust" containment buildings, was only used in the Soviet Union.[93] Over 10 RBMK reactors are still in use today. However, changes were made in both the RBMK reactors themselves (use of a safer enrichment of uranium) and in the control system (preventing safety systems being disabled), amongst other things, to reduce the possibility of a similar accident.[94] Russia now largely relies upon, builds and exports a variant of the PWR, the VVER, with over 20 in use today.

An international organization to promote safety awareness and the professional development of operators in nuclear facilities, the World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO), was created as a direct outcome of the 1986 Chernobyl accident. The organization was created with the intent to share and grow the adoption of nuclear safety culture, technology and community, where before there was an atmosphere of cold war secrecy.

Numerous countries, including Austria (1978), Sweden (1980) and Italy (1987) (influenced by Chernobyl) have voted in referendums to oppose or phase out nuclear power.

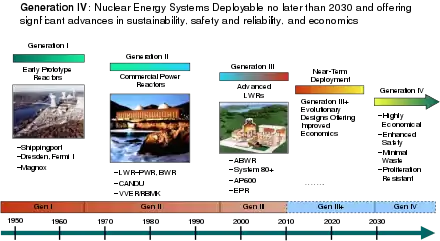

Nuclear renaissance

In the early 2000s, the nuclear industry was expecting a nuclear renaissance, an increase in the construction of new reactors, due to concerns about carbon dioxide emissions.[96] However, in 2009, Petteri Tiippana, the director of STUK's nuclear power plant division, told the BBC that it was difficult to deliver a Generation III reactor project on schedule because builders were not used to working to the exacting standards required on nuclear construction sites, since so few new reactors had been built in recent years.[97]

In 2018 the MIT Energy Initiative study on the future of nuclear energy concluded that, together with the strong suggestion that government should financially support development and demonstration of new Generation IV nuclear technologies, for a worldwide renaissance to commence, a global standardization of regulations needs to take place, with a move towards serial manufacturing of standardized units akin to the other complex engineering field of aircraft and aviation. At present it is common for each country to demand bespoke changes to the design to satisfy varying national regulatory bodies, often to the benefit of domestic engineering supply firms. The report goes on to note that the most cost-effective projects have been built with multiple (up to six) reactors per site using a standardized design, with the same component suppliers and construction crews working on each unit, in a continuous work flow.[98]

Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster

Following the Tōhoku earthquake on 11 March 2011, one of the largest earthquakes ever recorded, and a subsequent tsunami off the coast of Japan, the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant suffered three core meltdowns due to failure of the emergency cooling system for lack of electricity supply. This resulted in the most serious nuclear accident since the Chernobyl disaster.

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident prompted a re-examination of nuclear safety and nuclear energy policy in many countries[99] and raised questions among some commentators over the future of the renaissance.[100][96] Germany approved plans to close all its reactors by 2022. Italian nuclear energy plans[101] ended when Italy banned the generation, but not consumption, of nuclear electricity in a June 2011 referendum.[102][99] China, Switzerland, Israel, Malaysia, Thailand, United Kingdom, and the Philippines reviewed their nuclear power programs.[103][104][105][106]

In 2011 the International Energy Agency halved its prior estimate of new generating capacity to be built by 2035.[107][108] Nuclear power generation had the biggest ever fall year-on-year in 2012, with nuclear power plants globally producing 2,346 TWh of electricity, a drop of 7% from 2011. This was caused primarily by the majority of Japanese reactors remaining offline that year and the permanent closure of eight reactors in Germany.[109]

Post-Fukushima

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident sparked controversy about the importance of the accident and its effect on nuclear's future. The crisis prompted countries with nuclear power to review the safety of their reactor fleet and reconsider the speed and scale of planned nuclear expansions.[110] In 2011, The Economist opined that nuclear power "looks dangerous, unpopular, expensive and risky", and suggested a nuclear phase-out.[111] Jeffrey Sachs, Earth Institute Director, disagreed claiming combating climate change would require an expansion of nuclear power.[112] Investment banks were also critical of nuclear soon after the accident.[113][114]

In 2011 German engineering giant Siemens said it would withdraw entirely from the nuclear industry in response to the Fukushima accident.[115][116] In 2017, Siemens set the "milestone" of supplying the first additive manufacturing part to a nuclear power station, at the Krško Nuclear Power Plant in Slovenia, which it regards as an "industry breakthrough".[117]

The Associated Press and Reuters reported in 2011 the suggestion that the safety and survival of the younger Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant, the closest reactor facility to the epicenter and on the coast, demonstrate that it is possible for nuclear facilities to withstand the greatest natural disasters. The Onagawa plant was also said to show that nuclear power can retain public trust, with the surviving residents of the town of Onagawa taking refuge in the gymnasium of the nuclear facility following the destruction of their town.[118][119]

Following an IAEA inspection in 2012, the agency stated that "The structural elements of the [Onagawa] NPS (nuclear power station) were remarkably undamaged given the magnitude of ground motion experienced and the duration and size of this great earthquake,”.[120][121]

In February 2012, the U.S. NRC approved the construction of 2 reactors at the Vogtle Electric Generating Plant, the first approval in 30 years.[122][123]

Kharecha and Hansen estimated that "global nuclear power has prevented an average of 1.84 million air pollution-related deaths and 64 gigatonnes of CO2-equivalent (GtCO2-eq) greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that would have resulted from fossil fuel burning" and, if continued, it could prevent up to 7 million deaths and 240 GtCO2-eq emissions by 2050.[11]

In August 2015, following 4 years of near zero fission-electricity generation, Japan began restarting its nuclear reactors, after safety upgrades were completed, beginning with Sendai Nuclear Power Plant.[124]

By 2015, the IAEA's outlook for nuclear energy had become more promising. "Nuclear power is a critical element in limiting greenhouse gas emissions," the agency noted, and "the prospects for nuclear energy remain positive in the medium to long term despite a negative impact in some countries in the aftermath of the [Fukushima-Daiichi] accident...it is still the second-largest source worldwide of low-carbon electricity. And the 72 reactors under construction at the start of last year were the most in 25 years."[125] As of 2015 the global trend was for new nuclear power stations coming online to be balanced by the number of old plants being retired.[126] Eight new grid connections were completed by China in 2015.[127][128]

In 2016 the BN-800 sodium cooled fast reactor in Russia, began commercial electricity generation, while plans for a BN-1200 were initially conceived the future of the fast reactor program in Russia awaits the results from MBIR, an under construction multi-loop Generation research facility for testing the chemically more inert lead, lead-bismuth and gas coolants, it will similarly run on recycled MOX (mixed uranium and plutonium oxide) fuel. An on-site pyrochemical processing, closed fuel-cycle facility, is planned, to recycle the spent fuel/"waste" and reduce the necessity for a growth in uranium mining and exploration. In 2017 the manufacture program for the reactor commenced with the facility open to collaboration under the "International Project on Innovative Nuclear Reactors and Fuel Cycle", it has a construction schedule, that includes an operational start in 2020. As planned, it will be the world's most-powerful research reactor.[129]

In 2015 the Japanese government committed to the aim of restarting its fleet of 40 reactors by 2030 after safety upgrades, and to finish the construction of the Generation III Ōma Nuclear Power Plant.[130]

This would mean that approximately 20% of electricity would come from nuclear power by 2030. As of 2018, some reactors have restarted commercial operation following inspections and upgrades with new regulations.[131] While South Korea has a large nuclear power industry, the new government in 2017, influenced by a vocal anti-nuclear movement,[132] committed to halting nuclear development after the completion of the facilities presently under construction.[133][134][135]

The bankruptcy of Westinghouse in March 2017 due to US$9 billion of losses from the halting of construction at Virgil C. Summer Nuclear Generating Station, in the U.S. is considered an advantage for eastern companies, for the future export and design of nuclear fuel and reactors.[136]

In 2016, the U.S. Energy Information Administration projected for its “base case” that world nuclear power generation would increase from 2,344 terawatt hours (TWh) in 2012 to 4,500 TWh in 2040. Most of the predicted increase was expected to be in Asia.[137] As of 2018, there are over 150 nuclear reactors planned including 50 under construction.[138] In January 2019, China had 45 reactors in operation, 13 under construction, and plans to build 43 more, which would make it the world's largest generator of nuclear electricity.[139]

Future

_04790182_(8506930230).jpg.webp)

Zero-emission nuclear power is an important part of the climate change mitigation effort. Under IEA Sustainable Development Scenario by 2030 nuclear power and CCUS would have generated 3900 TWh globally while wind and solar 8100 TWh with the ambition to achieve net-zero CO

2 emissions by 2070.[141] In order to achieve this goal on average 15 GWe of nuclear power should have been added annually on average.[142] As of 2019 over 60 GW in new nuclear power plants was in construction, mostly in China, Russia, Korea, India and UAE.[142] Many countries in the world are considering Small Modular Reactors with one in Russia connected to the grid in 2020.

Countries with at least one nuclear power plant in planning phase include Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Egypt, Finland, Hungary, India, Kazakhstan, Poland, Saudi Arabia and Uzbekistan.[142]

The future of nuclear power varies greatly between countries, depending on government policies. Some countries, most notably, Germany, have adopted policies of nuclear power phase-out. At the same time, some Asian countries, such as China[139] and India,[143] have committed to rapid expansion of nuclear power. In other countries, such as the United Kingdom[144] and the United States, nuclear power is planned to be part of the energy mix together with renewable energy.

Nuclear energy may be one solution to providing clean power while also reversing the impact fossil fuels have had on our climate.[145] These plants would capture carbon dioxide and create a clean energy source with zero emissions, making a carbon-negative process. Scientists propose that 1.8 million lives have already been saved by replacing fossil fuel sources with nuclear power.[146]

Extending plant lifetimes

As of 2019 the cost of extending plant lifetimes is competitive with other electricity generation technologies, including new solar and wind projects.[6] In the United States, licenses of almost half of the operating nuclear reactors have been extended to 60 years.[149] The U.S. NRC and the U.S. Department of Energy have initiated research into Light water reactor sustainability which is hoped will lead to allowing extensions of reactor licenses beyond 60 years, provided that safety can be maintained, to increase energy security and preserve low-carbon generation sources. Research into nuclear reactors that can last 100 years, known as Centurion Reactors, is being conducted.[150]

As of 2020 a number of US nuclear power plants were cleared by Nuclear Regulatory Commission for operations up to 80 years.[8]

Nuclear power station

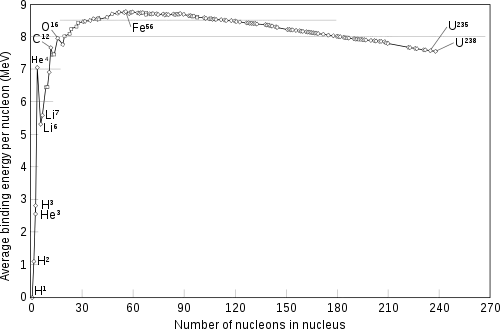

Just as many conventional thermal power stations generate electricity by harnessing the thermal energy released from burning fossil fuels, nuclear power plants convert the energy released from the nucleus of an atom via nuclear fission that takes place in a nuclear reactor. When a neutron hits the nucleus of a uranium-235 or plutonium atom, it can split the nucleus into two smaller nuclei. The reaction is called nuclear fission. The fission reaction releases energy and neutrons. The released neutrons can hit other uranium or plutonium nuclei, causing new fission reactions, which release more energy and more neutrons. This is called a chain reaction. The reaction rate is controlled by control rods that absorb excess neutrons. The controllability of nuclear reactors depends on the fact that a small fraction of neutrons resulting from fission are delayed. The time delay between the fission and the release of the neutrons slows down changes in reaction rates and gives time for moving the control rods to adjust the reaction rate.[151][152]

A fission nuclear power plant is generally composed of a nuclear reactor, in which the nuclear reactions generating heat take place; a cooling system, which removes the heat from inside the reactor; a steam turbine, which transforms the heat in mechanical energy; an electric generator, which transform the mechanical energy into electrical energy.[151]

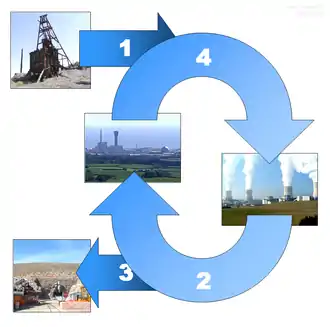

Life cycle of nuclear fuel

The life cycle of nuclear fuel starts with Uranium mining, which can be underground, open-pit, or in-situ leach mining, an increasing number of the highest output mines are remote underground operations, such as McArthur River uranium mine, in Canada, which by itself accounts for 13% of global production. The uranium ore, now independent from the ore body is then, as is shared in common with other metal mining, converted into a compact ore concentrate form, known in the case of uranium as "yellowcake"(U3O8) to facilitate transport.

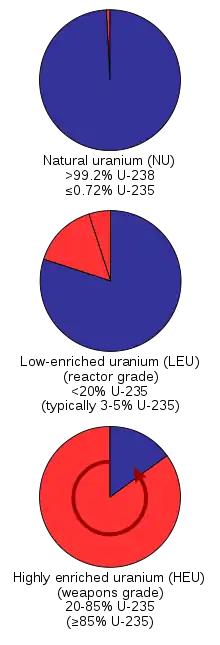

In reactors that can sustain the neutron economy with the use of graphite or heavy water moderators, the reactor fuel can be this natural uranium on reducing to the much denser black ceramic oxide (UO2) form. For light water reactors, the fuel for which requires a further isotopic refining, the yellowcake is converted to the only suitable monoatomic uranium molecule, that is a gas just above room temperature, uranium hexafluoride, which is then sent through gaseous enrichment. In civilian light water reactors, Uranium is typically enriched to 3-5% uranium-235, and then generally converted back into a black powdered ceramic uranium oxide(UO2) form, that is then compressively sintered into fuel pellets, a stack of which forms fuel rods of the proper composition and geometry for the particular reactor that the fuel is needed in.

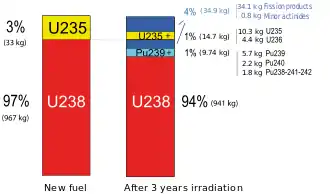

In modern light-water reactors the fuel rods will typically spend 3 operational cycles (about 6 years) inside the reactor, generally until about 3% of the uranium has been fissioned. Afterwards, they will be moved to a spent fuel pool which provides cooling for the thermal heat and shielding for ionizing radiation. Depending largely upon burnup efficiency, after about 5 years in a spent fuel pool the spent fuel is radioactively and thermally cool enough to handle, and can be moved to dry storage casks or reprocessed.

Conventional fuel resources

Uranium is a fairly common element in the Earth's crust: it is approximately as common as tin or germanium, and is about 40 times more common than silver.[153] Uranium is present in trace concentrations in most rocks, dirt, and ocean water, but is generally economically extracted only where it is present in high concentrations. As of 2011 the world's known resources of uranium, economically recoverable at the arbitrary price ceiling of US$130/kg, were enough to last for between 70 and 100 years.[154][155][156]

The OECD's red book of 2011 said that conventional uranium resources had grown by 12.5% since 2008 due to increased exploration, with this increase translating into greater than a century of uranium available if the rate of use were to continue at the 2011 level.[157][158] In 2007, the OECD estimated 670 years of economically recoverable uranium in total conventional resources and phosphate ores assuming the then-current use rate.[159]

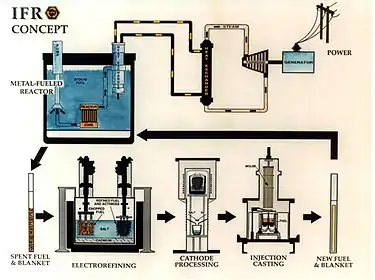

Light water reactors make relatively inefficient use of nuclear fuel, mostly fissioning only the very rare uranium-235 isotope.[160] Nuclear reprocessing can make this waste reusable.[160] Newer generation III reactors also achieve a more efficient use of the available resources than the generation II reactors which make up the vast majority of reactors worldwide.[160] With a pure fast reactor fuel cycle with a burn up of all the Uranium and actinides (which presently make up the most hazardous substances in nuclear waste), there is an estimated 160,000 years worth of Uranium in total conventional resources and phosphate ore at the price of 60–100 US$/kg.[161]

Unconventional uranium resources

Unconventional uranium resources also exist. Uranium is naturally present in seawater at a concentration of about 3 micrograms per liter,[162][163][164][165][166] with 4.5 billion tons of uranium considered present in seawater at any time. In 2012 it was estimated that this fuel source could be extracted at 10 times the current price of uranium.[167]

In 2014, with the advances made in the efficiency of seawater uranium extraction, it was suggested that it would be economically competitive to produce fuel for light water reactors from seawater if the process was implemented at large scale.[168] Uranium extracted on an industrial scale from seawater would constantly be replenished by both river erosion of rocks and the natural process of uranium dissolved from the surface area of the ocean floor, both of which maintain the solubility equilibria of seawater concentration at a stable level.[166] Some commentators have argued that this strengthens the case for nuclear power to be considered a renewable energy.[169]

Breeding

As opposed to light water reactors which use uranium-235 (0.7% of all natural uranium), fast breeder reactors use uranium-238 (99.3% of all natural uranium) or thorium. A number of fuel cycles and breeder reactor combinations are considered to be sustainable and/or renewable sources of energy.[170][171] In 2006 it was estimated that with seawater extraction, there was likely some five billion years' worth of uranium-238 for use in breeder reactors.[172]

Breeder technology has been used in several reactors, but the high cost of reprocessing fuel safely, at 2006 technological levels, requires uranium prices of more than US$200/kg before becoming justified economically.[173] Breeder reactors are however being pursued as they have the potential to burn up all of the actinides in the present inventory of nuclear waste while also producing power and creating additional quantities of fuel for more reactors via the breeding process.[174][175]

As of 2017, there are two breeders producing commercial power, BN-600 reactor and the BN-800 reactor, both in Russia.[176] The BN-600, with a capacity of 600 MW, was built in 1980 in Beloyarsk and is planned to produce power until 2025.[176] The BN-800 is an updated version of the BN-600, and started operation in 2014.[176] The Phénix breeder reactor in France was powered down in 2009 after 36 years of operation.[176]

Both China and India are building breeder reactors. The Indian 500 MWe Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor is in the commissioning phase,[177] with plans to build more.[178]

Another alternative to fast breeders are thermal breeder reactors that use uranium-233 bred from thorium as fission fuel in the thorium fuel cycle.[179] Thorium is about 3.5 times more common than uranium in the Earth's crust, and has different geographic characteristics.[179] This would extend the total practical fissionable resource base by 450%.[179] India's three-stage nuclear power programme features the use of a thorium fuel cycle in the third stage, as it has abundant thorium reserves but little uranium.[179]

Nuclear waste

.png.webp)

The most important waste stream from nuclear power reactors is spent nuclear fuel. From LWRs, it is typically composed of 95% uranium, 4% fission products from the energy generating nuclear fission reactions, as well as about 1% transuranic actinides (mostly reactor grade plutonium, neptunium and americium)[182] from unavoidable neutron capture events. The plutonium and other transuranics are responsible for the bulk of the long-term radioactivity, whereas the fission products are responsible for the bulk of the short-term radioactivity.[183]

High-level radioactive waste

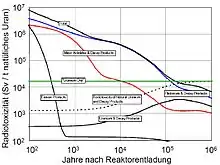

The high-level radioactive waste/spent fuel that is generated from power production, requires treatment, management and isolation from the environment. The technical issues in accomplishing this are considerable, due to the extremely long periods some particularly sublimation prone, mildly radioactive wastes, remain potentially hazardous to living organisms, namely the long-lived fission products, technetium-99 (half-life 220,000 years) and iodine-129 (half-life 15.7 million years),[190] which dominate the waste stream in radioactivity after the more intensely radioactive short-lived fission products(SLFPs)[184] have decayed into stable elements, which takes approximately 300 years. To successfully isolate the LLFP waste from the biosphere, either separation and transmutation,[184][191] or some variation of a synroc treatment and deep geological storage, is commonly suggested.[192][193][194][195]

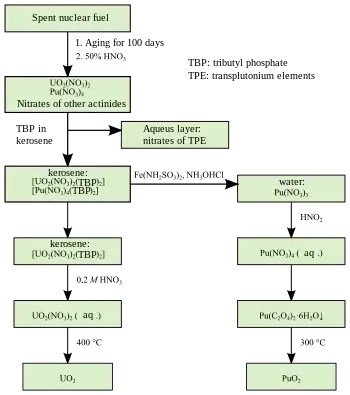

While in the US, spent fuel is presently in its entirety, federally classified as a nuclear waste and is treated similarly,[196] in other countries it is largely reprocessed to produce a partially recycled fuel, known as mixed oxide fuel or MOX. For spent fuel that does not undergo reprocessing, the most concerning isotopes are the medium-lived transuranic elements, which are led by reactor grade plutonium (half-life 24,000 years).[197]

Some proposed reactor designs, such as the American Integral Fast Reactor and the Molten salt reactor can more completely use or burnup the spent reactor grade plutonium fuel and other minor actinides, generated from light water reactors, as under the designed fast fission spectrum, these elements are more likely to fission and produce the aforementioned fission products in their place. This offers a potentially more attractive alternative to deep geological disposal.[198][199][200]

The thorium fuel cycle results in similar fission products, though creates a much smaller proportion of transuranic elements from neutron capture events within a reactor. Therefore, spent thorium fuel, breeding the true fuel of fissile uranium-233, is somewhat less concerning from a radiotoxic and security standpoint.[201]

Low-level radioactive waste

The nuclear industry also produces a large volume of low-level radioactive waste in the form of contaminated items like clothing, hand tools, water purifier resins, and (upon decommissioning) the materials of which the reactor itself is built. Low-level waste can be stored on-site until radiation levels are low enough to be disposed as ordinary waste, or it can be sent to a low-level waste disposal site.[202]

Waste relative to other types

In countries with nuclear power, radioactive wastes account for less than 1% of total industrial toxic wastes, much of which remains hazardous for long periods.[160] Overall, nuclear power produces far less waste material by volume than fossil-fuel based power plants.[203] Coal-burning plants are particularly noted for producing large amounts of toxic and mildly radioactive ash due to concentrating naturally occurring metals and mildly radioactive material in coal.[204] A 2008 report from Oak Ridge National Laboratory concluded that coal power actually results in more radioactivity being released into the environment than nuclear power operation, and that the population effective dose equivalent, or dose to the public from radiation from coal plants is 100 times as much as from the operation of nuclear plants.[205] Although coal ash is much less radioactive than spent nuclear fuel on a weight per weight basis, coal ash is produced in much higher quantities per unit of energy generated, and this is released directly into the environment as fly ash, whereas nuclear plants use shielding to protect the environment from radioactive materials, for example, in dry cask storage vessels.[206]

Waste disposal

Disposal of nuclear waste is often considered the most politically divisive aspect in the lifecycle of a nuclear power facility.[207] Presently, waste is mainly stored at individual reactor sites and there are over 430 locations around the world where radioactive material continues to accumulate. Some experts suggest that centralized underground repositories which are well-managed, guarded, and monitored, would be a vast improvement.[207] There is an "international consensus on the advisability of storing nuclear waste in deep geological repositories",[208] with the lack of movement of nuclear waste in the 2 billion year old natural nuclear fission reactors in Oklo, Gabon being cited as "a source of essential information today."[209][210]

There are no commercial scale purpose built underground high-level waste repositories in operation.[208][211][212][213] However, in Finland the Onkalo spent nuclear fuel repository of the Olkiluoto Nuclear Power Plant is under construction as of 2015.[214] The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico has been taking nuclear waste since 1999 from production reactors, but as the name suggests is a research and development facility. In 2014 a radiation leak caused by violations in the use of chemically reactive packaging[215] brought renewed attention to the need for quality control management, along with some initial calls for more R&D into the alternative methods of disposal for radioactive waste and spent fuel.[216] In 2017, the facility was formally reopened after three years of investigation and cleanup, with the resumption of new storage taking place later that year.[217]

The U.S Nuclear Waste Policy Act, a fund which previously received $750 million in fee revenues each year from the nation's combined nuclear electric utilities, had an unspent balance of $44.5 billion as of the end of FY2017, when a court ordered the federal government to cease withdrawing the fund, until it provides a destination for the utilities commercial spent fuel.[218]

Horizontal drillhole disposal describes proposals to drill over one kilometer vertically, and two kilometers horizontally in the earth's crust, for the purpose of disposing of high-level waste forms such as spent nuclear fuel, Caesium-137, or Strontium-90. After the emplacement and the retrievability period, drillholes would be backfilled and sealed.[219][220]

Reprocessing

Most thermal reactors run on a once-through fuel cycle, mainly due to the low price of fresh uranium, though many reactors are also fueled with recycled fissionable materials that remain in spent nuclear fuel. The most common fissionable material that is recycled is the reactor-grade plutonium (RGPu) that is extracted from spent fuel, it is mixed with uranium oxide and fabricated into mixed-oxide or MOX fuel. The first LWR designs certified to operate on a full core of MOX fuel, the ABWR and the System 80, began to appear in the 1990s.[227][228] The potential for recycling the spent fuel a second time is limited by undesirable neutron economy issues using second-generation MOX fuel in thermal-reactors. These issues do not affect fast reactors, which are therefore preferred in order to achieve the full energy potential of the original uranium.[229][230] The only commercial demonstration of twice recycled, high burnup fuel to date, occurred in the Phénix fast reactor.[231]

Because thermal LWRs remain the most common reactor worldwide, the most typical form of commercial spent fuel recycling is to recycle the plutonium a single time as MOX fuel, as is done in France, where it is considered to increase the sustainability of the nuclear fuel cycle, reduce the attractiveness of spent fuel to theft and lower the volume of high level nuclear waste.[232] Reprocessing of civilian fuel from power reactors is also currently done in the United Kingdom, Russia, Japan, and India.

The main constituent of spent fuel from the most common light water reactor, is uranium that is slightly more enriched than natural uranium, which can be recycled, though there is a lower incentive to do so. Most of this "recovered uranium",[233] or at times referred to as reprocessed uranium, remains in storage. It can however be used in a fast reactor, used directly as fuel in CANDU reactors, or re-enriched for another cycle through an LWR. The direct use of recovered uranium to fuel a CANDU reactor was first demonstrated at Quishan, China.[234] The first re-enriched uranium reload to fuel a commercial LWR, occurred in 1994 at the Cruas unit 4, France.[235][236] Re-enriching of reprocessed uranium is common in France and Russia.[237] When reprocessed uranium, namely Uranium-236, is part of the fuel of LWRs, it generates a spent fuel and plutonium isotope stream with greater inherent self-protection, than the once-thru fuel cycle.[238][239][240]

While reprocessing offers the potential recovery of up to 95% of the remaining uranium and plutonium fuel, in spent nuclear fuel and a reduction in long term radioactivity within the remaining waste. Reprocessing has been politically controversial because of the potential to contribute to nuclear proliferation and varied perceptions of increasing the vulnerability to nuclear terrorism and because of its higher fuel cost, compared to the once-through fuel cycle.[229][241] Similarly, while reprocessing reduces the volume of high-level waste, it does not reduce the fission products that are the primary residual heat generating and radioactive substances for the first few centuries outside the reactor, thus still requiring an almost identical container-spacing for the initial first few hundred years, within proposed geological waste isolation facilities. However much of the opposition to the Yucca Mountain project and those similar to it, primarily center not around fission products but the "plutonium mine" concern that placed in the underground, un-reprocessed spent fuel, will eventually become.[242][243]

In the United States, spent nuclear fuel is currently not reprocessed.[237] A major recommendation of the Blue Ribbon Commission on America's Nuclear Future was that "the United States should undertake...one or more permanent deep geological facilities for the safe disposal of spent fuel and high-level nuclear waste".[244]

The French La Hague reprocessing facility has operated commercially since 1976 and is responsible for half the world's reprocessing as of 2010.[245] Having produced MOX fuel from spent fuel derived from France, Japan, Germany, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands, with the non-recyclable part of the spent fuel eventually sent back to the user nation. More than 32,000 tonnes of spent fuel had been reprocessed as of 2015, with the majority from France, 17% from Germany, and 9% from Japan.[246] Once a source of criticism from Greenpeace, more recently the organization have ceased attempting to criticize the facility on technical grounds, having succeeded at performing the process without serious incidents that have been frequent at other such facilities around the world. In the past, the antinuclear movement argued that reprocessing would not be technically or economically feasible.[247] A PUREX related facility, frequently considered to be the proprietary COEX,[248] designed by Areva, is a major long-term commitment of the PRC with the intention to supply by 2030, Chinese reactors with economically separated and indigenous recycled fuel.[249][250]

Nuclear decommissioning

The financial costs of every nuclear power plant continues for some time after the facility has finished generating its last useful electricity. Once no longer economically viable, nuclear reactors and uranium enrichment facilities are generally decommissioned, returning the facility and its parts to a safe enough level to be entrusted for other uses, such as greenfield status. After a cooling-off period that may last decades, reactor core materials are dismantled and cut into small pieces to be packed in containers for interim storage or transmutation experiments.

In the United States a Nuclear Waste Policy Act and Nuclear Decommissioning Trust Fund is legally required, with utilities banking 0.1 to 0.2 cents/kWh during operations to fund future decommissioning. They must report regularly to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) on the status of their decommissioning funds. About 70% of the total estimated cost of decommissioning all U.S. nuclear power reactors has already been collected (on the basis of the average cost of $320 million per reactor-steam turbine unit).[251]

In the United States in 2011, there are 13 reactors that had permanently shut down and are in some phase of decommissioning.[252] With Connecticut Yankee Nuclear Power Plant and Yankee Rowe Nuclear Power Station having completed the process in 2006–2007, after ceasing commercial electricity production circa 1992. The majority of the 15 years, was used to allow the station to naturally cool-down on its own, which makes the manual disassembly process both safer and cheaper. Decommissioning at nuclear sites which have experienced a serious accident are the most expensive and time-consuming.

Installed capacity and electricity production

Nuclear fission power stations, excluding the contribution from naval nuclear fission reactors, provided 11% of the world's electricity in 2012,[254] somewhat less than that generated by hydro-electric stations at 16%. Since electricity accounts for about 25% of humanity's energy usage with the majority of the rest coming from fossil fuel reliant sectors such as transport, manufacture and home heating, nuclear fission's contribution to the global final energy consumption was about 2.5%.[255] This is a little more than the combined global electricity production from wind, solar, biomass and geothermal power, which together provided 2% of global final energy consumption in 2014.[256]

In addition, there were approximately 140 naval vessels using nuclear propulsion in operation, powered by about 180 reactors.[257][258]

Nuclear power's share of global electricity production has fallen from 16.5% in 1997 to about 10% in 2017, in large part because the economics of nuclear power have become more difficult.[259]

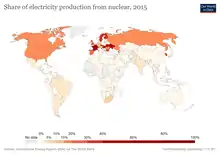

Regional differences in the use of nuclear power are large. The United States produces the most nuclear energy in the world, with nuclear power providing 20% of the electricity it consumes, while France produces the highest percentage of its electrical energy from nuclear reactors – 71% as of 2019.[65] In the European Union as a whole nuclear power provides 26% of the electricity as of 2018.[260] Nuclear power is the single largest low-carbon electricity source in the United States,[261] and accounts for two-thirds of the European Union's low-carbon electricity.[262] Nuclear energy policy differs among European Union countries, and some, such as Austria, Estonia, Ireland and Italy, have no active nuclear power stations.

Many military and some civilian (such as some icebreakers) ships use nuclear marine propulsion.[263] A few space vehicles have been launched using nuclear reactors: 33 reactors belong to the Soviet RORSAT series and one was the American SNAP-10A.

International research is continuing into additional uses of process heat such as hydrogen production (in support of a hydrogen economy), for desalinating sea water, and for use in district heating systems.[264]

Use in space

Both fission and fusion appear promising for space propulsion applications, generating higher mission velocities with less reaction mass. This is due to the much higher energy density of nuclear reactions: some 7 orders of magnitude (10,000,000 times) more energetic than the chemical reactions which power the current generation of rockets.

Radioactive decay has been used on a relatively small scale (few kW), mostly to power space missions and experiments by using radioisotope thermoelectric generators such as those developed at Idaho National Laboratory.

Economics

The economics of new nuclear power plants is a controversial subject, since there are diverging views on this topic, and multibillion-dollar investments depend on the choice of an energy source. Nuclear power plants typically have high capital costs for building the plant, but low fuel costs.

One of the most notable cons of nuclear energy as a climate change solution is the high cost of constructing nuclear power plants. Companies planning to build new nuclear plants estimate that it would cost between $6 billion to $9 billion for a 1,100 MW plant.[265] The Washington, DC-based research institute, Energy Impact Center,[266] and a private company in Oregon, NuScale Power,[267] is working to make nuclear plants more easily obtainable to power communities and lower carbon emissions in our atmosphere.

Comparison with other power generation methods is strongly dependent on assumptions about construction timescales and capital financing for nuclear plants as well as the future costs of fossil fuels and renewables as well as for energy storage solutions for intermittent power sources. On the other hand, measures to mitigate global warming, such as a carbon tax or carbon emissions trading, may favor the economics of nuclear power.[268][269]

Analysis of the economics of nuclear power must also take into account who bears the risks of future uncertainties. To date all operating nuclear power plants have been developed by state-owned or regulated electric utility monopolies[270] Many countries have now liberalized the electricity market where these risks, and the risk of cheaper competitors emerging before capital costs are recovered, are borne by plant suppliers and operators rather than consumers, which leads to a significantly different evaluation of the economics of new nuclear power plants.[271]

Nuclear power plants, though capable of some grid-load following, are typically run as much as possible to keep the cost of the generated electrical energy as low as possible, supplying mostly base-load electricity.[272]

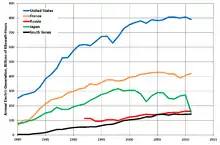

Peer reviewed analyses of the available cost trends of nuclear power, since its inception, show large disparity by nation, design, build rate and the establishment of familiarity in expertise. The two nations of which data were available, which have produced reactors at a lower cost trend than prior facilities in the 2000s were India and South Korea.[273] In the history of civilian reactor power, certain designs lent considerable early positive economics, over competitors, such as the CANDU, which realized much higher capacity factor and reliability when compared to generation II light water reactors up to about the 1990s.[274] At that time LWRs in the United States began to utilize higher enrichment, permitting longer operation times without stoppages. The CANDU design had allowed Canada to forego uranium enrichment facilities. Due to the on-line refueling reactor design, the larger set of PHWRs, of which the CANDU design is a part, continue to hold many world record positions for longest continual electricity generation, without stoppage, routinely close to and over 800 days, before maintenance checks.[275] The specific record as of 2019 is held by a PHWR at Kaiga Atomic Power Station, generating electricity continuously for 962 days.[276]

The PHWR fleet of India, in analysis by M.V. Ramana, were constructed, fuelled and continue to operate, close to the price of Indian coal power stations, [277] As of 2015, only the indigenously financed and constructed S.Korean OPR-1000 fleet, were completed at a similar price.[273]

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster was expected to increase the costs of operating and new LWR power stations, due to increased requirements for on-site spent fuel management and elevated design basis threats.[278][279]

The levelized cost of electricity from a new nuclear power plant is estimated to be 69 USD/MWh, according to an analysis by the International Energy Agency and the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency. This represents the median cost estimate for an nth-of-a-kind nuclear power plant to be completed in 2025, at a discount rate of 7%. Nuclear power was found to be the least-cost option among dispatchable technologies. However, variable renewables can generate cheaper electricity. The median cost of onshore wind power was estimated to be 50 USD/MWh, and utility-scale solar power 56 USD/MWh. At the assumed CO2 emission cost of USD 30 per ton, power from coal (88 USD/MWh) and gas (71 USD/MWh) is more expensive than low-carbon technologies. Electricity from long-term operation of nuclear power plants by lifetime extension was found the be the least-cost option, 32 USD/MWh.[280]

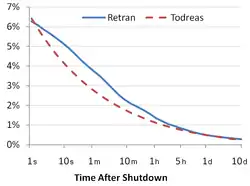

Accidents, attacks and safety

Nuclear reactors have three unique characteristics that affect their safety, as compared to other power plants. Firstly, intensely radioactive materials are present in a nuclear reactor. Their release to the environment could be hazardous. Secondly, the fission products, which make up most of the intensely radioactive substances in the reactor, continue to generate a significant amount of decay heat even after the fission chain reaction has stopped. If the heat cannot be removed from the reactor, the fuel rods may overheat and release radioactive materials. Thirdly, a criticality accident (a rapid increase of the reactor power) is possible in certain reactor designs if the chain reaction cannot be controlled. These three characteristics have to be taken into account when designing nuclear reactors.[281]

All modern reactors are designed so that an uncontrolled increase of the reactor power is prevented by natural feedback mechanisms: if the temperature or the amount of steam in the reactor increases, the fission rate inherently decreases by designing in a negative void coefficient of reactivity. The chain reaction can also be manually stopped by inserting control rods into the reactor core. Emergency core cooling systems (ECCS) can remove the decay heat from the reactor if normal cooling systems fail.[282] If the ECCS fails, multiple physical barriers limit the release of radioactive materials to the environment even in the case of an accident. The last physical barrier is the large containment building.[281] Approximately 120 reactors,[283] such as all those in Switzerland prior to and all reactors in Japan after the Fukushima accident, incorporate Filtered Containment Venting Systems, onto the containment structure, which are designed to relieve the containment pressure during an accident by releasing gases to the environment while retaining most of the fission products in the filter structures.[284]

Nuclear power with death rate of 0.07 per TWh remains the safest energy source per unit of energy compared to other energy sources.[285]

Accidents

Some serious nuclear and radiation accidents have occurred. The severity of nuclear accidents is generally classified using the International Nuclear Event Scale (INES) introduced by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The scale ranks anomalous events or accidents on a scale from 0 (a deviation from normal operation that poses no safety risk) to 7 (a major accident with widespread effects). There have been 3 accidents of level 5 or higher in the civilian nuclear power industry, two of which, the Chernobyl accident and the Fukushima accident, are ranked at level 7.

The Chernobyl accident in 1986 caused approximately 50 deaths from direct and indirect effects, and some temporary serious injuries.[288] The future predicted mortality from cancer increases, is usually estimated at some 4000 in the decades to come.[289][290][291] A higher number of the routinely treatable Thyroid cancer, set to be the only type of causal cancer, will likely be seen in future large studies.[292]

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident was caused by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. The accident has not caused any radiation-related deaths, but resulted in radioactive contamination of surrounding areas. The difficult Fukushima disaster cleanup will take 40 or more years, and is expected to cost tens of billions of dollars.[293][294] The Three Mile Island accident in 1979 was a smaller scale accident, rated at INES level 5. There were no direct or indirect deaths caused by the accident.

According to Benjamin K. Sovacool, fission energy accidents ranked first among energy sources in terms of their total economic cost, accounting for 41 percent of all property damage attributed to energy accidents.[296] Another analysis presented in the international journal Human and Ecological Risk Assessment found that coal, oil, Liquid petroleum gas and hydroelectric accidents (primarily due to the Banqiao dam burst) have resulted in greater economic impacts than nuclear power accidents.[297] Comparing Nuclear's latent cancer deaths, such as cancer with other energy sources immediate deaths per unit of energy generated (GWeyr). This study does not include Fossil fuel related cancer and other indirect deaths created by the use of fossil fuel consumption in its "severe accident", an accident with more than 5 fatalities, classification.

Nuclear power works under an insurance framework that limits or structures accident liabilities in accordance with the Paris convention on nuclear third-party liability, the Brussels supplementary convention, the Vienna convention on civil liability for nuclear damage[298] and the Price-Anderson Act in the United States. It is often argued that this potential shortfall in liability represents an external cost not included in the cost of nuclear electricity; but the cost is small, amounting to about 0.1% of the levelized cost of electricity, according to a CBO study.[299] These beyond-regular-insurance costs for worst-case scenarios are not unique to nuclear power, as hydroelectric power plants are similarly not fully insured against a catastrophic event such as the Banqiao Dam disaster, where 11 million people lost their homes and from 30,000 to 200,000 people died, or large dam failures in general. As private insurers base dam insurance premiums on limited scenarios, major disaster insurance in this sector is likewise provided by the state.[300]

Safety

In terms of lives lost per unit of energy generated, nuclear power has caused fewer accidental deaths per unit of energy generated than all other major sources of energy generation. Energy produced by coal, petroleum, natural gas and hydropower has caused more deaths per unit of energy generated due to air pollution and energy accidents. This is found when comparing the immediate deaths from other energy sources to both the immediate nuclear related deaths from accidents[301] and also including the latent, or predicted, indirect cancer deaths from nuclear energy accidents.[302] When the combined immediate and indirect fatalities from nuclear power and all fossil fuels are compared, including fatalities resulting from the mining of the necessary natural resources to power generation and to air pollution,[10] the use of nuclear power has been calculated to have prevented about 1.8 million deaths between 1971 and 2009, by reducing the proportion of energy that would otherwise have been generated by fossil fuels, and is projected to continue to do so.[303][11] Following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, it has been estimated that if Japan had never adopted nuclear power, accidents and pollution from coal or gas plants would have caused more lost years of life.[304]

Forced evacuation from a nuclear accident may lead to social isolation, anxiety, depression, psychosomatic medical problems, reckless behavior, even suicide. Such was the outcome of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster in Ukraine. A comprehensive 2005 study concluded that "the mental health impact of Chernobyl is the largest public health problem unleashed by the accident to date".[305] Frank N. von Hippel, an American scientist, commented on the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, saying that a disproportionate radiophobia, or "fear of ionizing radiation could have long-term psychological effects on a large portion of the population in the contaminated areas".[306] A 2015 report in Lancet explained that serious impacts of nuclear accidents were often not directly attributable to radiation exposure, but rather social and psychological effects. Evacuation and long-term displacement of affected populations created problems for many people, especially the elderly and hospital patients.[307] In January 2015, the number of Fukushima evacuees was around 119,000, compared with a peak of around 164,000 in June 2012.[308]

Attacks and sabotage

Terrorists could target nuclear power plants in an attempt to release radioactive contamination into the community. The United States 9/11 Commission has said that nuclear power plants were potential targets originally considered for the September 11, 2001 attacks. An attack on a reactor's spent fuel pool could also be serious, as these pools are less protected than the reactor core. The release of radioactivity could lead to thousands of near-term deaths and greater numbers of long-term fatalities.[309]

In the United States, the NRC carries out "Force on Force" (FOF) exercises at all nuclear power plant sites at least once every three years.[309] In the United States, plants are surrounded by a double row of tall fences which are electronically monitored. The plant grounds are patrolled by a sizeable force of armed guards.[310]

Insider sabotage is also a threat because insiders can observe and work around security measures. Successful insider crimes depended on the perpetrators' observation and knowledge of security vulnerabilities.[311] A fire caused 5–10 million dollars worth of damage to New York's Indian Point Energy Center in 1971.[312] The arsonist turned out to be a plant maintenance worker.[313] Some reactors overseas have also reported varying levels of sabotage by workers.[314]

Nuclear proliferation

Many technologies and materials associated with the creation of a nuclear power program have a dual-use capability, in that they can be used to make nuclear weapons if a country chooses to do so. When this happens a nuclear power program can become a route leading to a nuclear weapon or a public annex to a "secret" weapons program. The concern over Iran's nuclear activities is a case in point.[317]

As of April 2012 there were thirty one countries that have civil nuclear power plants,[318] of which nine have nuclear weapons, with the vast majority of these nuclear weapons states having first produced weapons, before commercial fission electricity stations. Moreover, the re-purposing of civilian nuclear industries for military purposes would be a breach of the Non-proliferation treaty, to which 190 countries adhere.

A fundamental goal for global security is to minimize the nuclear proliferation risks associated with the expansion of nuclear power.[317] The Global Nuclear Energy Partnership was an international effort to create a distribution network in which developing countries in need of energy would receive nuclear fuel at a discounted rate, in exchange for that nation agreeing to forgo their own indigenous develop of a uranium enrichment program. The France-based Eurodif/European Gaseous Diffusion Uranium Enrichment Consortium is a program that successfully implemented this concept, with Spain and other countries without enrichment facilities buying a share of the fuel produced at the French controlled enrichment facility, but without a transfer of technology.[319] Iran was an early participant from 1974, and remains a shareholder of Eurodif via Sofidif.

A 2009 United Nations report said that:

the revival of interest in nuclear power could result in the worldwide dissemination of uranium enrichment and spent fuel reprocessing technologies, which present obvious risks of proliferation as these technologies can produce fissile materials that are directly usable in nuclear weapons.[320]

On the other hand, power reactors can also reduce nuclear weapons arsenals when military grade nuclear materials are reprocessed to be used as fuel in nuclear power plants. The Megatons to Megawatts Program, the brainchild of Thomas Neff of MIT,[321][322] is the single most successful non-proliferation program to date.[315] Up to 2005, the Megatons to Megawatts Program had processed $8 billion of high enriched, weapons grade uranium into low enriched uranium suitable as nuclear fuel for commercial fission reactors by diluting it with natural uranium. This corresponds to the elimination of 10,000 nuclear weapons.[323] For approximately two decades, this material generated nearly 10 percent of all the electricity consumed in the United States (about half of all U.S. nuclear electricity generated) with a total of around 7 trillion kilowatt-hours of electricity produced.[324] Enough energy to energize the entire United States electric grid for about two years.[321] In total it is estimated to have cost $17 billion, a "bargain for US ratepayers", with Russia profiting $12 billion from the deal.[324] Much needed profit for the Russian nuclear oversight industry, which after the collapse of the Soviet economy, had difficulties paying for the maintenance and security of the Russian Federations highly enriched uranium and warheads.[321]

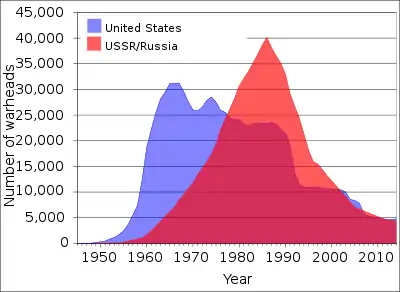

The Megatons to Megawatts Program was hailed as a major success by anti-nuclear weapon advocates as it has largely been the driving force behind the sharp reduction in the quantity of nuclear weapons worldwide since the cold war ended.[315] However without an increase in nuclear reactors and greater demand for fissile fuel, the cost of dismantling and down blending has dissuaded Russia from continuing their disarmament. As of 2013 Russia appears to not be interested in extending the program.[325]

Environmental impact

Carbon emissions

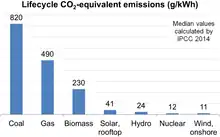

Nuclear power is one of the leading low carbon power generation methods of producing electricity, and in terms of total life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions per unit of energy generated, has emission values comparable to or lower than renewable energy.[327][328]

A 2014 analysis of the carbon footprint literature by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported that the embodied total life-cycle emission intensity of fission electricity has a median value of 12 g CO

2eq/kWh, which is the lowest out of all commercial baseload energy sources.[326][329]

This is contrasted with coal and natural gas at 820 and 490 g CO

2 eq/kWh.[326][329]

From the beginning of its commercialization in the 1970s, nuclear power has prevented the emission of about 64 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent that would have otherwise resulted from the burning of fossil fuels in thermal power stations.[11]

Radiation

The variation in a person's absorbed natural background radiation, averages 2.4 mSv/a globally but frequently varies between 1 mSv/a and 13 mSv/a depending in most part on the geology a person resides upon.[330] According to the United Nations (UNSCEAR), regular NPP/nuclear power plant operations including the nuclear fuel cycle, increases this amount to 0.0002 millisieverts (mSv) per year of public exposure as a global average.[330] The average dose from operating NPPs to the local populations around them is less than 0.0001 mSv/a.[330] The average dose to those living within 50 miles of a coal power plant is over three times this dose, 0.0003 mSv/a.[331]

As of a 2008 report, Chernobyl resulted in the most affected surrounding populations and male recovery personnel receiving an average initial 50 to 100 mSv over a few hours to weeks, while the remaining global legacy of the worst nuclear power plant accident in average exposure is 0.002 mSv/a and is continually dropping at the decaying rate, from the initial high of 0.04 mSv per person averaged over the entire populace of the Northern Hemisphere in the year of the accident in 1986.[330]

Renewable energy and nuclear power

Slowing global warming requires a transition to a low-carbon economy, mainly by burning far less fossil fuel. Limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees C is technically possible if no new fossil fuel power plants are built from 2019.[332] This has generated considerable interest and dispute in determining the best path forward to rapidly replace fossil-based fuels in the global energy mix,[333][334] with intense academic debate.[335][336] Sometimes the IEA says that countries without nuclear should develop it as well as their renewable power.[337]