The Dreaming

Dreaming (also the Dreaming, the Dreamings and the Dreamtime) is a term devised by early anthropologists to refer to a religio-cultural worldview attributed to Australian Aboriginal beliefs. It was originally used by Francis Gillen, quickly adopted by his colleague Baldwin Spencer and thereafter popularised by A. P. Elkin, who, however, later revised his views. The Dreaming is used to represent Aboriginal concepts of Everywhen during which the land was inhabited by ancestral figures, often of heroic proportions or with supernatural abilities. These figures were often distinct from gods as they did not control the material world and were not worshipped, but only revered. The concept of the dreamtime has subsequently become widely adopted beyond its original Australian context and is now part of global popular culture.

The term is based on a rendition of the Arandic word alcheringa, used by the Aranda (Arunta, Arrernte) people of Central Australia, although it has been argued that it is based on a misunderstanding or mistranslation. Some scholars suggest that the word's meaning is closer to "eternal, uncreated."[2] Anthropologist William Stanner said that the concept was best understood by non-Aboriginal people as "a complex of meanings".[3]

By the 1990s, Dreaming had acquired its own currency in popular culture, based on idealised or fictionalised conceptions of Australian mythology. Since the 1970s, Dreaming has also returned from academic usage via popular culture and tourism and is now ubiquitous in the English vocabulary of Aboriginal Australians in a kind of "self-fulfilling academic prophecy".[2][lower-alpha 1]

Origin of the term

The station-master, magistrate, and amateur ethnographer Francis Gillen first used the terms in an ethnographical report in 1896. With Walter Baldwin Spencer, Gillen published a major work, Native Tribes of Central Australia, in 1899.[4] In that work, they spoke of the Alcheringa as "the name applied to the far distant past with which the earliest traditions of the tribe deal".[5][lower-alpha 2] Five years later, in their Northern Tribes of Central Australia, they gloss the far distant age as "the dream times", link it to the word alcheri meaning 'dream', and affirm that the term is current also among the Kaitish and Unmatjera.[6]

Altjira

Early doubts about the precision of Spencer and Gillen's English gloss were expressed by the German Lutheran pastor and missionary Carl Strehlow in his 1908 book Die Aranda (The Arrernte). He noted that his Arrente contacts explained altjira, whose etymology was unknown, as an eternal being who had no beginning. In the Upper Arrernte language, the proper verb for 'to dream' was altjirerama, literally 'to see God'. Strehlow theorised that the noun is the somewhat rare word altjirrinja, which Spencer and Gillen gave a corrupted transcription and a false etymology. "The native," Strehlow concluded, "knows nothing of 'dreamtime' as a designation of a certain period of their history."[7][lower-alpha 3]

Strehlow gives Altjira or Altjira mara (mara meaning 'good') as the Arrente word for the eternal creator of the world and humankind. Strehlow describes him as a tall strong man with red skin, long fair hair, and emu legs, with many red-skinned wives (with dog legs) and children. In Strehlow's account, Altjira lives in the sky (which is a body of land through which runs the Milky Way, a river).[8]

However, by the time Strehlow was writing, his contacts had been converts to Christianity for decades, and critics suggested that Altjira had been used by missionaries as a word for the Christian God.[8]

In 1926, Spencer conducted a field study to challenge Strehlow's conclusion about Altjira and the implied criticism of Gillen and Spencer's original work. Spencer found attestations of altjira from the 1890s that used the word to mean 'associated with past times' or 'eternal', not 'god'.[8]

Academic Sam Gill finds Strehlow's use of Altjira ambiguous, sometimes describing a supreme being, and sometimes describing a totem being but not necessarily a supreme one. He attributes the clash partly to Spencer's cultural evolutionist beliefs that Aboriginal people were at a pre-religion "stage" of development (and thus could not believe in a supreme being), while Strehlow as a Christian missionary found presence of belief in the divine a useful entry point for proselytising.[8]

Linguist David Campbell Moore is critical of Spencer and Gillen's "Dreamtime" translation, concluding:[9]

"Dreamtime" was a mistranslation based on an etymological connection between "a dream" and "Altjira", which held only over a limited geographical domain. There was some semantic relationship between "Altjira" and "a dream", but to imagine that the latter captures the essence of "Altjira" is an illusion.

Other Aboriginal language terms

The complex of religious beliefs encapsulated by the Dreamings are also called:

- Ngarrankarni or Ngarrarngkarni by the Gija people[3]

- Jukurrpa or Tjukurpa/Tjukurrpa by the Warlpiri people and in the Pitjantjatjara dialect[3][10] [11][12]

- Ungud or Wungud by the Ngarinyin people[3]

- Manguny in the language Martu Wangka[3]

- Wongar in North-East Arnhem Land[3]

- Daramoolen in Ngunnawal language and Ngarigo language[10]

- Nura in the Dharug language[10]

Translations

In English, anthropologists have variously translated words normally understood to mean Dreaming or Dreamtime in a variety of other ways, including "Everywhen", "world-dawn", "ancestral past", "ancestral present", "ancestral now" (satirically), "unfixed in time", "abiding events" or "abiding law".[13]

Most translations of the Dreaming into other languages are based on the translation of the word dream. Examples include Espaces de rêves in French ('dream spaces') and Snivanje in Croatian (a gerund derived from the verb for 'to dream').[14]

The concept of the Dreaming is inadequately explained by English terms, and difficult to explain in terms of non-Aboriginal cultures. It has been described as "an all-embracing concept that provides rules for living, a moral code, as well as rules for interacting with the natural environment ... [it] provides for a total, integrated way of life ... a lived daily reality". It embraces past, present and future.[12]

Aboriginal beliefs and culture

Related entities are known as Mura-mura by the Dieri and as Tjukurpa in Pitjantjatjara.

"Dreaming" is now also used as a term for a system of totemic symbols, so that an Aboriginal person may "own" a specific Dreaming, such as Kangaroo Dreaming, Shark Dreaming, Honey Ant Dreaming, Badger Dreaming, or any combination of Dreamings pertinent to their country. This is because in the Dreaming an individual's entire ancestry exists as one, culminating in the idea that all worldly knowledge is accumulated through one's ancestors. Many Aboriginal Australians also refer to the world-creation time as "Dreamtime". The Dreaming laid down the patterns of life for the Aboriginal people.[15]

Creation is believed to be the work of culture heroes who travelled across a formless land, creating sacred sites and significant places of interest in their travels. In this way, "songlines" (or Yiri in the Warlpiri language) were established, some of which could travel right across Australia, through as many as six to ten different language groupings. The dreaming and travelling trails of these heroic spirit beings are the songlines. The signs of the spirit beings may be of spiritual essence, physical remains such as petrosomatoglyphs of body impressions or footprints, among natural and elemental simulacra.

Some of the ancestor or spirit beings inhabiting the Dreamtime become one with parts of the landscape, such as rocks or trees.[16] The concept of a life force is also often associated with sacred sites, and ceremonies performed at such sites "are a re-creation of the events which created the site during The Dreaming". The ceremony helps the life force at the site to remain active and to keep creating new life: if not performed, new life cannot be created.[17]

Dreaming existed before the life of the individual begins, and continues to exist when the life of the individual ends. Both before and after life, it is believed that this spirit-child exists in the Dreaming and is only initiated into life by being born through a mother. The spirit of the child is culturally understood to enter the developing fetus during the fifth month of pregnancy.[18] When the mother felt the child move in the womb for the first time, it was thought that this was the work of the spirit of the land in which the mother then stood. Upon birth, the child is considered to be a special custodian of that part of their country and is taught the stories and songlines of that place. As Wolf (1994: p. 14) states: "A 'black fella' may regard his totem or the place from which his spirit came as his Dreaming. He may also regard tribal law as his Dreaming."

In the Wangga genre, the songs and dances express themes related to death and regeneration.[19] They are performed publicly with the singer composing from their daily lives or while Dreaming of a nyuidj (dead spirit).[20]

Dreaming stories vary throughout Australia, with variations on the same theme. The meaning and significance of particular places and creatures is wedded to their origin in The Dreaming, and certain places have a particular potency or Dreaming. For example, the story of how the sun was made is different in New South Wales and in Western Australia. Stories cover many themes and topics, as there are stories about creation of sacred places, land, people, animals and plants, law and custom. In Perth, the Noongar believe that the Darling Scarp is the body of the Wagyl – a serpent being that meandered over the land creating rivers, waterways and lakes and who created the Swan River. In another example, the Gagudju people of Arnhemland, for which Kakadu National Park is named, believe that the sandstone escarpment that dominates the park's landscape was created in the Dreamtime when Ginga (the crocodile-man) was badly burned during a ceremony and jumped into the water to save himself.

In popular culture

An early reference is found in Richard McKenna's 1960s speculative fiction novella, Fiddler's Green, which mentions "Alcheringa ... the Binghi spirit land", i.e. the Aranda concept translated as "Dreamtime". Early 1970s references to the concept include Dorothy Bryant's The Kin of Ata are Waiting for You (1971), Ursula K. Le Guin's novella The Word for World is Forest (1972), and Peter Weir's films The Last Wave (1977) and Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975).

Dreamtime became a widely cited concept in popular culture in the 1980s, and by the late 1980s was adopted as a cliché in New Age and feminist spirituality alongside related appeals to other "Rouseauian natural people", such as the Native Americans idealized in 1960s hippie counterculture.[21]

1980s

- Philip K. Dick uses Dreamtime, among a plethora of other concepts, to describe his breakdown in his novel VALIS (1981).

- A 1982 album by Kate Bush is entitled The Dreaming, the title track of which deals with the upheaval and displacement of the Aboriginal people.

- A scene in the 1983 movie The Right Stuff shows Aboriginals partaking in a Dreaming ceremony just outside the Muchea Tracking Station while astronaut Gordon Cooper maintained radio communication with Astronaut John Glenn, who was experiencing a potentially catastrophic equipment malfunction during the Mercury-Atlas 6 spaceflight.

- During the 1980s, the UK band The Stranglers recorded an album called Dreamtime, with a title track inspired by the Aboriginal concept.

- The Cult's 1984 album is entitled Dreamtime. The album deals with indigenous-peoples themes, owing to singer Ian Astbury's interest in the book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.

- Werner Herzog's Where the Green Ants Dream (Wo die grünen Ameisen träumen) (1984) posited an Aboriginal protest against uranium mining based on the taboo against disturbing the dream of green ants and thus causing the destruction of the world.

- Frog Dreaming (1986) (renamed The Quest when released in the USA) included certain aspects of Aboriginal Dreaming.

- Daryl Hall solo single "Dreamtime" (1986).

- Bruce Chatwin wrote the blended fiction/non-fiction novel, The Songlines (1987), in exploration of some important Aboriginal concepts.

- The Star Trek novel Strangers from the Sky (1987) by Margaret Wander Bonanno has Captain Kirk using Dreamtime to investigate an altered reality.

- Steve Roach's 1988 album is entitled Dreamtime Return. The album deals with the concept of the Dreamtime.

- The Marvel Comics character Gateway, an Aboriginal "mutant" that lives in the Outback and first appeared in a 1988 Uncanny X-Men comic, accesses Dreamland through his mutant powers, giving him precognition and the ability to teleport others from place to place.

1990s

- Neil Gaiman's graphic novel The Sandman (1989–March 1996) is partially set in "The Dreaming", referred to in early volumes as "Dreamtime", and also reference "Fiddler's Green".

- Dreamtime Village, an intentional community in Wisconsin founded in 1990, dedicated to "various permaculture, hypermedia, and sustainability projects".

- British Folk Metal band Skyclad have a polemical song on their debut album The Wayward Sons of Mother Earth (1991) called "Trance Dance (A Dreamtime Walkabout)", whose narrator is Aboriginal.

- Spider Robinson's trilogy Stardance touches upon this in the second volume (1991).

- In The Maxx, The Outback represents a primeval landscape of a fictional Australia where the characters travel from the real world. The Outback takes heavy inspiration from Australian Aboriginal Dreamtime.

- Chapter 7 of Don Rosa's 12-part comic book series The Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck (1992-1994) is titled Dreamtime Duck of the Never-Never (1993). Set in 1896, the chapter shows a young Scrooge McDuck encountering an Aboriginal Elder on a pilgrimage.

- In issues #89–90 of DC Comics's Hellblazer, John Constantine ventures into the Dreamtime.

- In the episode "Walkabout" of the animated series Gargoyles, an Aboriginal mentor to Dingo teaches him of the Dreamtime. In the same episode, Goliath and Dingo enter the Dreamtime in order to communicate with an AI nanotech entity called the Matrix.

- Grant Morrison's character King Mob in his comic The Invisibles (1994–2000) visits Uluru and speaks telepathically with an Aboriginal Elder, he remarks that this is possible because he is a "Scorpion dreaming".

- Tad Williams four-volume science fiction epic Otherland (1996) touches upon Dreamtime and other aboriginal myths.

- "In the Dreamtime", a song written by Ralph McTell, was used in Billy Connoly's World Tour of Australia (1996).

- Terry Pratchett's novel The Last Continent (1998) uses several Dreamtime concepts.

2000s

- In Big Finish Productions Doctor Who audio drama, Dreamtime (2005), the Seventh Doctor and his companions deal with Aboriginal mysticism and Uluru.

- The Italian painter Giuliano Ghelli painted a series of canvases informally known as "aborigeni" inspired by a trip to Australia and a reading of Bruce Chatwin's novel The Songlines.[22]

- Alexis Wright's novel Carpentaria (2006) alludes to Dreaming narrative from the Gulf of Carpentaria through her stories of contemporary Aboriginal characters, a form of Australian magical realism.

- Sandra McDonald's novels, The Outback Stars, The Stars Down Under and The Stars Blue Yonder (2007–2009), use Aboriginal myth extensively.

- The film Australia (2008) includes aspects of Aboriginal Dreaming (songlines).

- The Finnish band Korpiklaani recorded a track called "Uniaika" (Dreamtime) on the album Karkelo in 2009.

- Tuomas Holopainen's 2014 album Music Inspired by the Life and Times of Scrooge includes a track entitled "Dreamtime," which directly references the Scrooge McDuck comic Dreamtime Duck of the Never-Never, and includes a didgeridoo in its instrumentation.

- Sam Kieth's comic Maxx relies heavily on the psychology and concept of Dreamtime.

- Jeff Smith says that aspects of his cartoon/fantasy epic Bone were inspired by Dreamtime, among other things.[23]

- Queenie Chan's manga The Dreaming (2005) takes place in Australia and deals with students from a boarding school who mysteriously go missing. Aboriginal legends feature in the series.

- Betty Clawman from DC Comics' New Guardians was an Aboriginal girl chosen to be part of the next stage in man's evolution – i.e. the New Guardians. Dreamtime figured in the story.

- Wildstorm's Planetary issue #15 briefly deals with the Dreamtime.

- In the graphic novel Y: The Last Man, the protagonist's love interest, Beth, spends time in Australia. Events in the Dreamtime are presented as a possible reason for the worldwide plague that killed almost all male mammals.

- In Dreamfall: The Longest Journey and Dreamfall Chapters there's a place which draws heavily from the concept of Dreamtime, as well as from other Aboriginal mythologies: the Storytime. It is described as the place where every story begins and ends.

- In Ty the Tasmanian Tiger, the Dreaming/Dreamtime is an alternate universe inhabited by mystical beings known as the Bunyip, the title characters family is sealed within the Dreaming by Boss Cass before the events of the first game, and in Ty the Tasmanian Tiger 3: Night of the Quinkan, Dreamtime becomes a warzone between the Bunyip and the Quinkan.

- In the third Sly Cooper game Sly 3: Honor Among Thieves, Murray is a student of Dreamtime, and his master joins the gang as well.

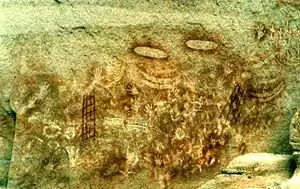

- In the animated series ExoSquad, two of the main characters talk to an Aboriginal aid who explains the nature of the Dreamtime and the cave art are shown depicting their current events.

- The Australian fantasy superhero television series Cleverman draws its premise and many concepts from various Dreaming stories, including those of the "hairymen", a monster known as the Namorrodor, and the Cleverman himself. The Dreaming is referenced explicitly several times.

See also

- Dreaming (Australian Aboriginal art)

- Aboriginal mythology

- Apeiron, the concept of the eternal or unlimited in Greek philosophy

- Wuji (philosophy) and Taiji (philosophy), concepts of the eternal or limitless in Chinese philosophy

Notes

- Stanner warned about uncritical use of the term and was aware of its semantic difficulties, while at the same time he continued using it and contributed to its popularisation; according to Swain it is "still used uncritically in contemporary literature".

- "the dim past to which the natives give the name of the 'Alcheringa'." (p.119)

- The Strehlows' informant, Moses (Tjalkabota), was a convert to Christianity, and the adoption of his interpretation suffered from a methodological error, according to Barry Hill, since his conversion made his views on pre-contact beliefs unreliable.

Citations

- Walsh 1979, pp. 33–41.

- Swain 1993, p. 21.

- Nicholls 2014a.

- James 2015, p. 36.

- Spencer & Gillen 1899, p. 73 n.1, 645.

- Spencer & Gillen 1904, p. 745.

- Hill 2003, pp. 140–141.

- Gill 1998, pp. 93–103.

- Moore 2016, pp. 85–108.

- Nicholls 2014b.

- "Jukurrpa". Jukurrpa Designs. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- Nicholls, Christine Judith (22 January 2014). "'Dreamtime' and 'The Dreaming' – an introduction". The Conversation. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- Swain 1993, pp. 21–22.

- Nicholls 2014c.

- Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Korff, Jens (8 February 2019). "What is the 'Dreamtime' or the 'Dreaming'?". Creative Spirits. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- "The Dreaming: Sacred sites". Working with Indigenous Australians. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- Bates 1996.

- Marett 2005, p. 1.

- Povinelli 2002, p. 200.

- di Leonardo 2000, p. 377 n.42.

- Vanni & Pedretti 2005, pp. 18, 70.

- Smith, Bone–A–Fides section.

Sources

- Bates, Daisy (1996). Aboriginal Perth and Bibbulmun biographies and legends. Hesperion Press.

- Bellah, Robert N. (2013) [First published 1970]. "Religious Evolution". In Eisenstadt, S.N. (ed.). Readings in Social Evolution and Development. Elsevier. pp. 211–244. ISBN 978-1-483-13786-5.

- Charlesworth, Max; Murphy, Howard; Bell, Diane; Maddock, Kenneth (1984). "Introduction". Religion In Aboriginal Australia: An Anthology. University of Queensland Press.

- "the Dreaming". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- Gill, Sam D. (1998). Storytracking: Texts, Stories & Histories in Central Australia. Oxford University Press. pp. 93–103. ISBN 978-0195115871.

- Hill, Barry (2003). Broken Song: T G H Strehlow and Aboriginal Possession. Knopf-Random House. ISBN 978-1-742-74940-2.

- Isaacs, Jennifier (1980). Australian Dreaming: 40,000 Years of Aboriginal History. Sydney: Lansdowne Press. ISBN 0-7018-1330-X.

- James, Diana (2015). "Tjukurpa Time". In McGrath, Ann; Jebb, Mary Anne (eds.). Long History, Deep Time: Deepening Histories of Place. Australian National University Press. pp. 33–46. ISBN 9781--925-02253-7.

- Lawlor, Robert (1991). Voices of the First Day: Awakening in the Aboriginal dreamtime. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International. ISBN 0-89281-355-5.

- di Leonardo, Micaela (2000). Exotics at Home: Anthropologies, Others, and American Modernity. University of Chicago Press. p. 377 n.42. ISBN 9780226472645.("Into the Crystal Dreamtime", promotional pamphlet, late 1980s; "Crystal Woman: isters of the Dreamtime" 1987; p. 36:"the prescriptive New Age genre, which sells one-hundred-proof ethnological antimodernism without overmuch worry about bothersome ethnographic facts")

- Marett, Allan (2005). Songs, Dreamings, and Ghosts: The Wangga of North Australia. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8195-6618-8.

- Moore, David (1 January 2016). Altjira, Dream and God. pp. 85–108. ISBN 978-1472443830.

- Nicholls, Christine Judith (22 January 2014a). "'Dreamtime' and 'The Dreaming': An introduction". The Conversation. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Nicholls, Christine Judith (28 January 2014c). "'Dreamtime' and 'The Dreaming': Who dreamed up these terms?". The Conversation. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Nicholls, Christine Judith (5 February 2014b). "'Dreamings' and dreaming narratives: What's the relationship?". The Conversation. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Povinelli, Elizabeth A. (2002). The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-8223-2868-1.

- Price-Williams, Douglas (1987). "The waking dream in ethnographic perspective". In Tedlock, Barbara (ed.). Dreaming: Anthropological and Psychological Interpretations. Cambridge University Press. pp. 246–262. ISBN 978-0-521-34004-5.

- Price-Williams, Douglas (2016). "Altjira, Dream and God". In Cox, James L.; Possamai, Adam (eds.). Religion and non-religion among Australian Aboriginal Peoples. Routledge. pp. 85–108. ISBN 978-1-317-06795-5.

- Smith, Jeff. Bone #46, Tenth Anniversary. Self-published. Bone-A–Fides section.

- Spencer, Baldwin; Gillen, F. J. (1899). Native Tribes of Central Australia. Macmillan & Co.

- Spencer, Baldwin; Gillen, F. J. (1904). The northern tribes of central Australia. Macmillan & Co.

- Spencer, Walter Baldwin; Gillen, Francis James (1968) [First published 1899]. The Native Tribes of Central Australia. New York: Dover.

- Stanner, Bill (1979). White Man Got No Dreaming: Essays 1938–1973. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

- Stanner, W. H. (1968). After The Dreaming. Boyer Lecture Series. ABC.

- Swain, Tony (1993). A Place for Strangers: Towards a History of Australian Aboriginal Being. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44691-4.

- Vanni, Maurizio; Pedretti, Carlo (2005). Giuliano Ghelli. Le vie del tempo (in Italian, English, and German). Poggibonsi (province of Siena), Italy: Carlo Cambi Editore. pp. 18, 70. ISBN 88-88482-41-5.

Ghelli's work appears as an authentic initiatory experience, with important ordeals to overcome. No Aboriginal boy can be considered a man, nor can an Aboriginal girl marry, until he or she has overcome all the initiatory rituals. One of these, perhaps the most feared, is the interpretation of symbols in paintings associated with Dreamtime.

- Voigt, Anna; Drury, Neville (1997). Wisdom of the Earth: the living legacy of the Aboriginal dreamtime. East Roseville, NSW: Simon & Schuster.

- Walsh, G. L. (1979). "Mutilated hands or signal stencils? A consideration of irregular hand stencils from Central Queensland" (PDF). Australian Archaeology. 9 (9): 33–41. doi:10.1080/03122417.1979.12093358. hdl:2328/708.

- Wolf, Fred Alan (1994). The Dreaming Universe: a mind-expanding journey into the realm where psyche and physics meet. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-74946-3.

- Wolfe, Patrick (1997). "Should the Subaltern Dream? "Australian Aborigines" and the Problem of Ethnographic Ventriloquism". In Humphreys, Sarah C. (ed.). Cultures of Scholarship. University of Michigan Press. pp. 57–96. ISBN 978-0-472-06654-4.

Further reading

| Library resources about Dreamtime |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dreamtime. |

- Goddard, Cliff; Wierzbicka, Anna (2015). "What does Jukurrpa ('Dreamtime', 'the Dreaming') mean? A semantic and conceptual journey of discovery" (PDF). Australian Aboriginal Studies (1): 34–65.