The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane

The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane is a 1976 cross-genre film directed by Nicolas Gessner and starring Jodie Foster, Martin Sheen, Alexis Smith, Mort Shuman, and Scott Jacoby. It was a co-production of Canada and France and written by Laird Koenig, based on his 1974 novel of the same title.

| The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane | |

|---|---|

Promotional poster for U.S. release | |

| Directed by | Nicolas Gessner |

| Produced by | Zev Braun |

| Written by | Laird Koenig |

| Based on | The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane by Laird Koenig |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Christian Gaubert[1] |

| Cinematography | René Verzier[2] |

| Edited by | Yves Langlois[2] |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes[5] |

| Country | |

| Language | English |

The plot focuses on 13-year-old Rynn Jacobs (Foster), a child whose absent poet father and secretive behaviours prod the suspicions of her conservative small-town Maine neighbours. The adaptation, originally intended as a play, was filmed in Quebec on a small budget. The production later became the subject of controversy over reports that Foster had conflicts with producers over the filming and inclusion of a nude scene, though a body double had been utilized. After a screening at the 1976 Cannes Film Festival, a court challenge was launched regarding distribution, and a general release followed in 1977.

Initially released to mixed reviews, with some critics finding the murder mystery plot weak but Foster's performance more meritorious, the film won two Saturn Awards, including Best Horror Film. It subsequently attained cult status, with later critics positively reviewing the screenplay. Writers and academics have interpreted it as a statement on children's rights and variously placed it in the thriller, horror, mystery or other genres.

Plot

On Halloween in the seaside town of Wells Harbor, Maine, Rynn Jacobs is celebrating her thirteenth birthday alone in her father Lester's house. Lester was a poet and the two recently moved from England, where he leased the house for three years. Frank Hallet, the adult son of landlady Cora Hallet, visits and makes sexual advances toward Rynn. Cora Hallet later arrives at the house, searching for Rynn's father. Rynn claims he is in New York and taunts the landlady about her son. The situation becomes more tense when Mrs. Hallet insists on retrieving her jelly glasses from the cellar. Rynn steadfastly refuses to let her into the cellar, and Mrs. Hallet leaves. She returns later and ignoring Rynn's warnings, opens the trap door to go into the cellar. Suddenly terrified by something she sees, Mrs. Hallet attempts to flee, but accidentally knocks down the cellar door support, fatally hitting her head on the door.

Trying to hide evidence of Mrs. Hallet's visit, Rynn goes outside to move her car. Her inability to start it attracts the attention of Mario, a young magician and the nephew of Officer Miglioriti, a local police officer who had previously given Rynn a ride home from town. Mario helps her move the car, and they have dinner together at Rynn's house. Miglioriti stops by to tell them that Frank Hallet has reported his mother missing, and asks to see Rynn's father, but Mario covers by saying that her father has gone to bed. Later that night, Frank Hallet makes a surprise visit. Suspicious, and looking for answers about the whereabouts of his mother and Rynn's father, he tries to scare Rynn into talking by killing her pet hamster. Mario chases Frank away, and Rynn now trusts him enough to show him her secret. Her terminally ill father and abusive mother divorced long ago. To protect Rynn from being returned to her mother's custody after his death, he moved them to an isolated area and made plans to allow Rynn to live alone, then committed suicide in the ocean so that his body would not be found. He also left Rynn with a jar of potassium cyanide, telling her that it was a sedative, to give to her mother if she ever came for her. Rynn coolly recounts how she put the powder in her mother's tea and watched her die. She learned embalming at the library in order to hide the body in the cellar.

The trust between Rynn and Mario blossoms into romance. They bury the corpses in the garden during a heavy rain, and Mario catches a cold. Miglioriti, suspicious of Rynn's excuses for her father's absence, again returns to the house. When he asks to see her father, Mario, disguised as an old man, comes down the stairs and introduces himself as Lester Jacobs.

After winter sets in, Rynn learns that Mario's cold has developed into pneumonia and he is in the hospital. Rynn goes to see him, but he is unconscious and she feels lonelier than ever before.

That night, as Rynn is going to bed, she is shocked to find Frank coming out of the cellar. Having put the pieces together and knowing the truth about Rynn's parents, he attempts to blackmail her, offering to protect her secrets in exchange for sexual favours. Rynn, seemingly defeated and resigned to Frank's demands, agrees to his suggestion that they have a cup of tea. Rynn places a dose of the potassium cyanide into her own cup and then takes the tea and almond cookies to the living room. Suspicious, Frank switches his cup with hers, and Rynn watches as he begins to succumb to the poison.

Cast

- Jodie Foster as Rynn Jacobs, a girl who lives on her own.

- Jodie's sister Connie Foster serves as Jodie's uncredited double in a scene where Rynn is naked.

- Martin Sheen as Frank Hallet, grown son of Rynn's landlady.

- Alexis Smith as Mrs. Cora Hallet, the mother of Frank Hallet and Rynn's landlady.

- Mort Shuman as Officer Ron Miglioriti, a police officer who often visits Rynn.

- Scott Jacoby as Mario, the nephew of Officer Miglioriti who befriends Rynn.

Themes

Felicia Feaster, writing for Turner Classic Movies, found an "unusual theme" in the film, which she interpreted as being one of independence for children.[7] Professor James R. Kincaid read the film as a call for children's rights.[8] T.S. Kord wrote the film argued that a child with money and a home does not need a parent if he or she does not believe it is necessary. The adults who attempt to intrude in Rynn's affairs are a threat, including her mother, her landlord, and the molester.[9]

Writer Anthony Synnott placed The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane in a trend of sexualizing children in film, calling Rynn the "murdering nymphet" and comparing her to Foster's child prostitute character Iris in Taxi Driver (1976).[10] Anthony Cortese also referred to Foster as giving an "encore performance" of Taxi Driver, calling Rynn "a 13-year-old imp of maturing sexuality".[11] Scholar Andrew Scahill described it as fitting a cinematic narrative of children in rebellion, one in which the child appears seemly, as with The Innocents (1961), The Omen (1976) and others.[12]

The genre has been debated, with Feaster arguing it was more psychological thriller than horror.[7] Jim Cullen summed the film up as "a strange hybrid" of genres, being a horror, thriller and feminist film.[13] Kord listed it among dramas about "Eerie, malevolent or criminal children", distinct from depictions of children in the supernatural horror genre.[14] Martin Sheen said it was a horror film in some ways, but "not overt", with mystery and suspense elements.[15] However, director Nicolas Gessner denied it was horror, characterizing it as "a teenage love story".[16]

Production

Development

Novelist Laird Koenig adapted the book himself.[17] Originally, the script was intended as a play, but this idea was abandoned due to the belief that a young actress would not be available to play Rynn for an extended period.[16] Gessner read the book, only to find rights were optioned to Sam Spiegel, but the project was derailed due to creative differences, allowing Gessner to secure them.[16]

The film followed tax incentives for cinema offered by the government of Canada, beginning in 1974, stimulating a "Hollywood North".[18] It was a co-production of Canada and France,[19] with Zev Braun producing as head of Zev Braun Productions, based in Los Angeles, alongside L.C.L. Industries in Montreal and Filmedis-Filmel in Paris.[20][21] Canadian producer Denis Héroux, who during the decade specialized in popular cinema with financiers from outside the country, also worked on the project.[22] It was shot on a small budget.[17] Financiers disliked how in the novel, Rynn murdered Mrs. Hallet with poisonous gas, causing the scene to be rewritten so the death is accidental.[16]

Casting

Director Martin Scorsese was editing Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore, and Gessner's look at his work led him to discover Jodie Foster.[16] With the guidance of her mother Brandy, Jodie took the role of Rynn,[23] and turned 13 while the film was being shot.[24] She wore a wig for the film, and a gap was added in her teeth.[25]

Sheen said he was contacted by Gessner personally about playing Frank Hallet, which Sheen accepted because he found the part intriguing and because he believed Foster had a promising career.[15] Gessner claimed Sheen was initially more interested in playing Mario, but Gessner persuaded Sheen that he was too old for that part. Gessner noted that casting Alexis Smith, who was born in Canada, also helped secure Canadian tax incentives.[16]

Filming

The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane was filmed in Montreal[15] and Knowlton, Quebec.[26] Sheen described the set as relaxed and as encouraging creativity, and said Foster also built a friendship with his daughter Renée Estevez during shooting.[15]

A producer's desire for "sex and violence" led to a nude scene depicting Rynn being added to the film. Foster strongly objected, saying "I walked off the set".[27] As a result, her older sister Connie acted as the nude double.[28] Her mother had suggested Connie, who was 21 at the time.[29] Following the release of Taxi Driver, the industry shared stories of Foster having conflicts during the production of The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane.[30] However, Gessner claimed Foster only regretted the scene after it was shot, and her request that it be deleted was denied by the Canadian producers.[16]

The crew built a false trapdoor for Mrs. Hallet's death scene, though Gessner acknowledged Smith was nervous about the effect.[16] For the scene where Frank Hallet kills the hamster Gordon, Sheen handled a dead and frozen rodent, and attempted to make it seem like it was still alive. Sound effects of squealing were also added.[15] The dead hamster was obtained from a hospital which carried out animal research, while the live hamster portraying Gordon in other scenes was given to the costume designer after production.[16]

Music

Mort Shuman, who played Officer Miglioriti, was a musician in real life, so the crew intended that Shuman would also write the film score. However, Shuman's arranger Christian Gaubert wrote the bulk of the music, giving him the credit of composer, while Shuman was listed as the music supervisor.[16]

Gessner wanted to use the music of Polish composer and pianist Frédéric Chopin, finding his music a good match with the dialogue. He said Chopin's music was intended to symbolize hope and absolution, along with sadness.[16] Chopin's piano concerto No. 1 in E Minor was performed by pianist Claudio Arrau and The London Philharmonic Orchestra.[20]

Release

After a screening at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1976,[3][4] Astral Bellevue Pathé Limited sold distribution rights to The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane, allowing it to make $750,000 worldwide by June.[31] The film was shown in Paris with a French dub on 26 January and in Toronto on 28 January 1977.[2] According to Variety, Beachfront Properties secured a temporary restraining order which gave it ownership of the film per a contract from September 1976. This order forbade any new sales but would not change the American International Pictures scheduled April 1977 release.[1] The film had trial screenings in Albuquerque and Peoria, Illinois on 18 March 1977.[1] It opened in Los Angeles on 11 May and in New York City on 10 August 1977,[1] with a PG rating.[32]

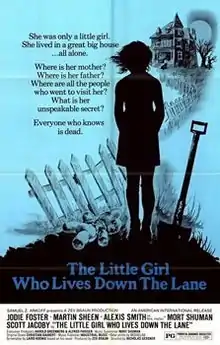

On its initial release, the film poster depicted The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane as a horror film, with an image of a building evoking the 1960 film Psycho and the subtitle "She was only a little girl. She lived in a great big house...all alone. Where is her mother? Where is her father? Where are all the people who went to visit her? What is her unspeakable secret? Everyone who knows is dead."[7]

A VHS release of the film removed the nudity, but it was re-added to the DVD.[17] StudioCanal published a DVD in Region 2 on 20 October 2008.[33] Kino Lorber released the film on Blu-ray in Region A on 10 May 2016.[34] Hulu and Amazon Prime also made the film available to their customers in November 2016.[35][36]

Reception

Critical reception

Janet Maslin, writing for The New York Times, said this was Foster's most natural portrayal of a child and that Sheen was frightening, and found the romance to be the greatest strength.[32] In The Washington Post, Gary Arnold called the film engaging, but claimed the murder plot is "too glib, too immorally contrived, to be satisfying."[19] Variety's review stated the story was unbelievable, and the romance was one of the few positive aspects.[37] Time's Christopher Porterfield felt the film failed to address the most interesting mysteries, and that doing so, combined with Foster's acting, would have made the film memorable.[38] Judith Crist's New York Post review judged it to be "a better-than-average thriller".[39] Foster's biographer Louis Chunovic referred to the film as "much maligned".[30]

Felicia Feaster of TCM remarked that The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane became a cult film, noting Danny Peary profiled it in his Guide for the Film Fanatic.[7] Peary also listed it in his book Cult Horror Movies.[40] In 1992, James Monaco gave the film three and a half stars, assessing it as disturbing and complimenting the performances and writing.[41] In their DVD and Video Guide 2005, Mick Martin and Marsha Porter awarded it three and a half stars, commenting it was "remarkably subdued".[42] Author David Greven praised Foster for a performance "achingly" suggesting "adolescent anomie".[43] In his 2015 Movie Guide, Leonard Maltin gave the film three stars, declaring it as a "Complex, unique mystery".[44] The film has a 90% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 10 reviews.[45]

Accolades

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturn Awards | 14 January 1978 | Best Horror Film | The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane | Won | [46] |

| Best Actress | Jodie Foster | Won | |||

| Best Director | Nicolas Gessner | Nominated | [24] | ||

| Best Supporting Actress | Alexis Smith | Nominated | |||

| Best Writing | Laird Koenig | Nominated | |||

References

- "The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- "Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane, The". Library and Archives Canada. Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- "Jodie Foster To Be Honored at the 2016 British Academy Britannia Awards". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. 26 September 2016. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- Chunovic 1995, p. 35.

- "The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane (1976)". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- "La Petite fille au bout du chemin". Bifi.fr. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- Feaster, Felicia. "The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- Kincaid 1998, p. 127.

- Kord 2016, p. 176.

- Synnott 2011, p. 37.

- Cortese 2006, p. 86.

- Scahill 2015.

- Cullen 2013, p. 188-189.

- Kord 2016, p. 3.

- Sheen, Martin (2016). Back Down the Lane: Martin Sheen on The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane (Blu-ray). Kino Lorber.

- Gessner, Nicolas (2016). The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane commentary (Blu-ray). Kino Lorber.

- Barrett, Michael (25 May 2016). "The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- Gold, Daniel M. (15 February 2017). "Recalling When Canada Was 'Hollywood North'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- Arnold, Gary (17 May 1977). "Promising, Precocious 'Little Girl'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- "The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane". Filmfacts. Division of Cinema of the University of Southern California. 20: 134. 1977.

- "La Petite Fille au bout du chemin". La Revue du cinéma. Ligue française de l'enseignement et de l'éducation permanente (319–323): 211. 1977.

- Glassman, Marc (2011). "Groundbreaking filmmaker was also a savvy businessman". Playback. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- Sonneborn 2014, p. 74.

- Jacobs, Christopher P. (18 January 2017). "Overlooked Thriller Turns 40". High Plains Reader. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- Erb 2010, p. 95.

- Pratley 2003, p. 127.

- Erb 2010, p. 94-95.

- Snodgrass 2008, p. 285.

- "Kid Thriller". Cosmopolitan. Vol. 183. Hearst Corporation. 1977. p. 304.

- Chunovic 1995, p. 33.

- Tadros, Connie (June–July 1976). "Cannes: Commercial Results". Cinema Canada. p. 23.

- Maslin, Janet (11 August 1977). "Screen: But When She Was Bad..." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- Anderson, Martin (13 October 2008). "The Little Girl Who Lives Down The Lane DVD review". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on 11 March 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- Anderson, Melissa (10 May 2016). "Disappearing Acts: Preminger's 'Bunny Lake' Still Entices, as Does Teenage Jodie Foster". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- Guerrasio, Jason (26 October 2016). "The best movies and TV shows coming to Amazon, HBO, and Hulu in November". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- Lapin, Andrew (October 2016). "What's New on Hulu: November 2016". Vulture.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- Staff (31 December 1976). "Review: 'The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane'". Variety. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- Porterfield, Christopher (1977). "The New Waif". Time. Vol. 110 no. 1–9. p. 210.

- "The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane". Filmfacts. Division of Cinema of the University of Southern California. 20: 135. 1977.

- Peary 2014.

- Monaco 1992, p. 480.

- Martin & Porter 2004, p. 649.

- Greven 2011, p. 149.

- Maltin 2014.

- "The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane (1976)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- "Past Saturn Awards". saturnawards.org. Archived from the original on 1 June 2007. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

Bibliography

- Chunovic, Louis (1995). Jodie: A Biography. Contemporary Books. ISBN 0809234041.

- Cortese, Anthony (2006). Opposing Hate Speech. Westport, Connecticut and London: Praeger. ISBN 0275984273.

- Cullen, Jim (28 February 2013). Sensing the Past: Hollywood Stars and Historical Visions. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199927669.

- Erb, Cynthia (2010). "Jodie Foster and Brooke Shields: 'New Ways to Look at the Young'". Hollywood Reborn: Movie Stars of the 1970s. New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813549523.

- Greven, David (25 April 2011). Representations of Femininity in American Genre Cinema: The Woman's Film, Film Noir, and Modern Horror. Springer. ISBN 0230118836.

- Kincaid, James Russell (1998). Erotic Innocence: The Culture of Child Molesting. Durham and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 0822321939.

- Kord, T.S. (25 July 2016). Little Horrors: How Cinema's Evil Children Play on Our Guilt. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Publishers. ISBN 1476626669.

- Maltin, Leonard (2014). Leonard Maltin's 2015 Movie Guide. New York: Signet. ISBN 0698183614.

- Martin, Mick; Porter, Marsha (2004). DVD and Video Guide 2005. Ballantine. ISBN 0345449959.

- Monaco, James (1992). The Movie Guide. Perigee Books. ISBN 0399517804.

- Peary, Danny (7 October 2014). Cult Horror Movies: Discover the 33 Best Scary, Suspenseful, Gory, and Monstrous Cinema Classics. Workman Publishing. ISBN 0761181709.

- Pratley, Gerald (2003). A Century of Canadian Cinema: Gerald Pratley's Feature Film Guide, 1900 to the Present. Lynx Images. ISBN 1894073215.

- Scahill, Andrew (30 September 2015). "Malice in Wonderland: The Terrible Performativity of Childhood- A Basket Full of Performance". The Revolting Child in Horror Cinema: Youth Rebellion and Queer Spectatorship. Springer. ISBN 1137481323.

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2008). Beating the Odds: A Teen Guide to 75 Superstars Who Overcame Adversity. Westport, Connecticut and London: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313345651.

- Sonneborn, Liz (14 May 2014). A to Z of American Women in the Performing Arts. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438107900.

- Synnott, Anthony (31 December 2011). "Little Angels, Little Devils: A Sociology of Children". A to Z of American Women in the Performing Arts (Second ed.). New Brunswick, United States and London: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0202364704.